Maya Angelou explores suffering, inequality and a people’s refusal to give up in this hard-hitting poem.

“One of the brightest lights of our time – a brilliant writer and a fierce friend. She… helped generations of Americans find their rainbow amidst the clouds…”

Barack Obama, on the passing of Maya Angelou, 2014

It’s hard to overestimate Maya Angelou’s achievements in literature and other spheres of public life, from her beginnings in St Louis, 1928 to her recent death in 2014. Her list of awards and accolades eclipses most other writers: she received over 50 honorary degrees, for a start, and in 2010, after a lifetime of acting, writing, directing, activism, teaching – even singing, dancing and composing – Angelou was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom (the highest civilian honour) by President Obama. Seemingly quite slight next to her autobiographical writing and essays, this poem stands out: her poetry was more often appreciated for the light it shone on the lives of people in America from the time of slavery to the civil rights movement of the 1960s than for its artistic craft. You may agree with me though, when you read Caged Bird, that it does both:

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun’s rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown and longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing breeze

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn-bright lawn

and he names the sky his own.

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

Using birds as a motif to represent parts of the human condition is not unusual in literature: poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote The Caged Skylark, in which his caged bird was a metaphor for being trapped in our own bodies. Maya Angelou’s autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings tells of her childhood growing up in America before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended segregation in public and began to tackle discrimination in employment, education and other spheres of life. In this poem, Angelou compares the life of a bird who is free to fly, enjoy nature and relax when he pleases, with a bird shut up in a cage. He can only stalk from one end of his cage to the other. He can’t fly because his wings are clipped – he can barely even see through the narrow bars of his cage. In fact, the only freedom left for him is to open his throat to sing.

The poem begins unexpectedly (given the title) with a description of the life of a free bird. And what a life he enjoys. He ‘leaps’ through the sky, exploring the world as far as he is able. He ‘floats downstream,’ following the course of a mighty river until it reaches the sea. The choice of word ‘floats’ underlines how effortless the free bird’s life is: the river will carry him wherever he needs to go. He floats ’till the current ends’ which is a metaphor suggesting that he can fly as long as he likes, until the river meets the sea, at which point his horizons widen and he can fly out over the entire ocean! In this way the river represents opportunities that life brings the free bird, and implies that they are practically endless. The free bird is warmed by the sun and, in another metaphor (‘dips his wings’), has the freedom to interact with the world too. The sun is a symbol representing warmth, life, luxury. Wherever the free bird chooses to go, he is guaranteed a life of ease and relaxation.

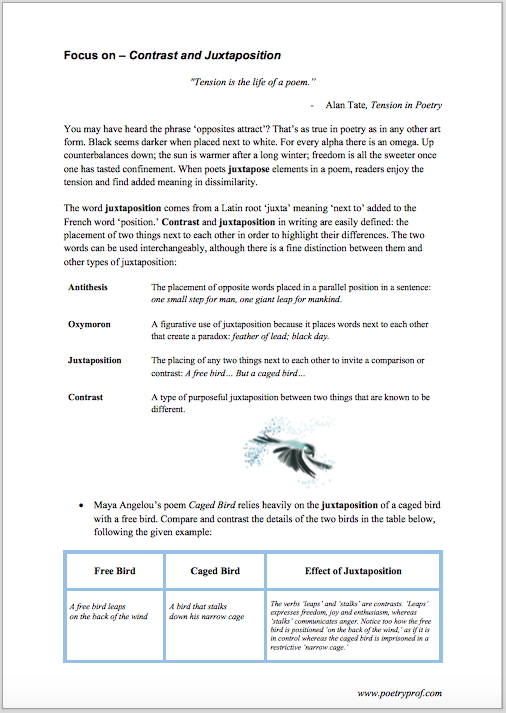

Almost every word in the free bird’s life speaks of freedom and indulgence: he leaps where the caged bird stalks; he floats where the caged bird stands; he dips his wing in the orange sun’s rays while the caged bird is associated with shadow. The most obvious technique in this poem is juxtaposition: you can try to pair almost everything the free bird enjoys with its exact opposite in the caged bird’s world. Images as well as words are juxtaposed: the free bird dares to claim the sky. By contrast, the caged bird stands on a grave of dreams. Juxtaposition is all about creating contrast in ideas, words and even sounds. Look at these examples from stanza four, in which the free bird enjoys dining on fat worms: he is associated with languorous, warm liquid W and nasal M, N sounds: winds, worms, waiting, dawn, lawn. The sounds blend and harmonize in a way that creates euphony. Apart from shadow shouts, the caged bird’s lines contain a mixture of various hard consonants: grave, dreams, nightmare, scream, clipped, tied. Combining different hard consonant sounds is called cacophony: in combination with diction (nightmare, shout, screams) it effectively suggests the terrible psychic state of a bird or person confined all their lives.

Parallels with and allusions to the history of the African-American slave trade, and subsequent social injustice between blacks and whites, are scattered through the poem. Details such as the carefully manicured lawns enjoyed by wealthy plantation owners, who used slaves to grow cash crops like cotton and sugar, and trade winds (easterly winds that blow round the equator; they helped early sailing ships travel from Europe and Africa to the Americas – the word trade alludes to the slave trade) help contextualise Angelou’s poem. Other freedoms which were taken away from enslaved people on plantations were the freedom to own property and even the right to name one’s own children. Often, children born on plantations were given the names of the white plantation owners. When the free bird is able to name the sky his own, he is actually exercising basic rights that were denied his enslaved brethren.

The most important symbol in the poem is the cage which traps the bird. It is both physical (narrow) and figurative, therefore, it restrains both the bird’s body and its soul. Firstly its wings are clipped and feet are tied. The bird is unable to exercise his most natural birth-right – his instinctive need to fly. But the cage also alters the bird psychologically: it is fearful, suffers from nightmares, and is sometimes provoked to anger: bars of rage, scream, shout. This idea is what give the poem most of its pathos. Imagine a child being tied up and locked in a dark room – or a person doomed lifelong to threats, abuse and torture on a plantation. These images should stir a strong reaction.

The caged bird’s song is an important allusion. Slaves working on plantations not only kept their spirits up through song, most were denied basic education so could not read or write, and would have had almost no access to pen, ink and paper in any case: song was a way of preserving stories, cultures, and traditions of people when they had no way to physically record anything, and a vessel for passing history from one generation to the next. Later, particularly in the 1950s to 1970s, songs would become indelibly linked with the civil rights protest movement. Today, African-American culture, most affected by the history and consequences of the slave trade, is powerfully expressed through rap, hip-hop, R’n’B, jazz and blues and other musical forms. When Angelou repeats the entire third verse as the last, she is creating a refrain or chorus, drawing attention to form: this is Maya Angelou’s own protest song. In fact, Angelou often performed readings of poetry and prose to spellbound crowds; her readings are rich in African-American oral traditions.

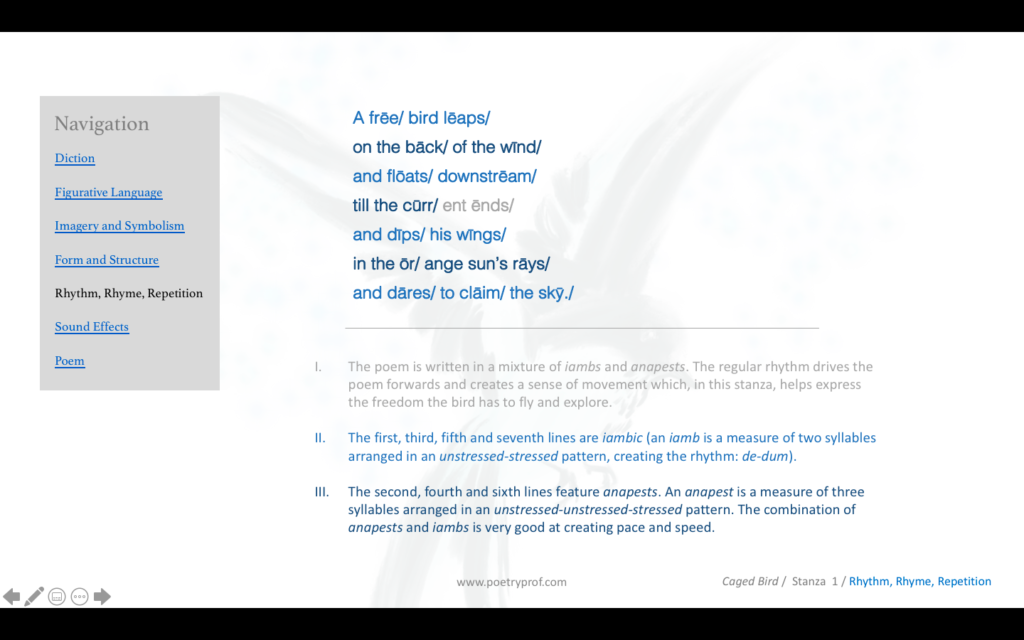

A major aspect of any song is rhythm, and Angelou’s song has its own iambic meter (de-dum, de-dum, de-dum). The effects of rhythm becomes even more telling when you compare two of the first three verses side by side with accents marked:

A frēe/ bird lēaps/

on the bāck/ of the wīnd/

and flōats/ downstrēam/

till the cūrr/ ent ēnds/

and dīps/ his wīngs/

in the ōr/ ange sun’s rāys/

and dāres/ to clāim/ the skȳ./

But a bīrd/ that stālks/

down his nārr/ ow cāge/

can sēl/ dom sēe/ (through)

his bārs/ of rāge/

his wīngs/ are clīpped/ (and)

his fēet/ are tīed/

so he ōp/ ens his thrōat/ to sīng./

Here, each emphasized syllable is marked with an accent and the unstressed syllables left clear. You can easily discover a recurring pattern. Slashes (/) indicate where the pattern repeats – each repeating set is called a foot. You should see that most lines in the first three stanzas have two feet, dimeter, with occasional lines of tri-meter. Now, look more closely at the number of stressed and unstressed syllables in each foot: some have one and others two unstressed syllables. ‘Unstressed-stressed’ patterns are called iambs; ‘unstressed-unstressed-stressed’ is an anapaest. You can see that the free bird has far more anapaests than his caged friend: the longer foot is both faster and more drawn-out, much better at communicating the free bird’s lively, easy existence. The caged bird is almost always given a shorter, more truncated iambic foot – rhythm as a kind of ‘prison’ for the words. There are also examples of lines given extra unstressed syllables (in brackets). This technique, called catalexis, has the words trying to ‘break out’ of the rhythmic prison, and makes the lines feel less comfortable. On the other hand, the iambic rhythm is strong. It persists. No matter what indignities and suffering the caged bird is forced to endure, it will persist rebelliously – even if the only act left is to sing hopelessly through the bars of a cage.

Actually, so much of the twin birds’ opposite experiences are suggested through aspects of form. Each stanza written in one unbroken sentence seems to suggest both freedom and entrapment, whichever way you look at it. For example, each stanza begins with a capitalised letter and ends in a full stop. All the other lines flow from one to the next without break or mark. In writing like this Angelou employs a technique called enjambment (from the French ‘enjamb’ meaning ‘to straddle’). If you asked me to consider the effects of this on the free bird, I might suggest that the lines flowing freely expresses the freedom he has to roam and fly from one place to another, unhindered. It also connects to the wind and stream: the lines flow like water and air. On the other hand, if you ask me to look at each stanza in light of the caged bird’s experience, I might reply that the capital letter and full stop function as ‘blocks’ or walls, beyond which the caged bird may not pass. It’s the perfect marriage of form and content.

To some, the way Angelou uses enjambment may seem arbitrary. But take a closer look at, say, verse one and you’ll notice and floats, and dips, and dares: all these lines begin with and. Enjambment draws your attention to this little word because it represents freedom of choice – look at all the things the free bird can do, one after the other (linking items in a list using ‘and’ in this way is a technique called polysyndeton). Similarly, in a verse describing the caged bird:

stalks down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped

his feet are tied

Again, notice the way Angelou carefully chooses the points where lines end and begin: his bars, his wings, his feet. Repeating words at the beginning of a line is a special form of repetition called anaphora. In this verse it nicely creates the impression of the bird stalking to and fro down a narrow, shortened cage. Having nowhere to go, he turns to retrace his steps down the same path over and over. This impression is heightened by rhyme: cage/rage. In fact, in the third stanza describing the caged bird’s song, trill, still and hill all rhyme. Creating ‘bonds’ between lines like this is a way of representing the bonds trapping the caged bird. The strongest rhyme in the poem is also the strongest image: as the caged bird stands on the grave of dreams/ his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream.

Importantly, the poem does not entirely exonerate the free bird from the burden of obligation it should have towards its caged cousin. After all, historically, it was so that some people could freely indulge in every whimsy and comfort that others found themselves segregated, exploited or enslaved. Parts of this poem are a reminder that injustices such as these couldn’t happen without complicity; throughout history a blind eye has been turned by so many to the suffering of others. Therefore, when the caged bird sings, his fearful trill is heard on the distant hill. Others can hear his plight, but what do they do about it? The sequence of stanzas comes into play here – after hearing the song, the free bird continues to think of another breeze. He does not allow the misery of his fellow bird to turn his mind from thoughts of luxury: fat worms and dawn-bright lawns. It reminds me of Pastor Martin Niemoller’s famous quotation/poem: first they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out… then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out… then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out…

By now, you might feel a little beaten down by the pessimism and the troubling themes, including allusion to slavery, of the poem. Remember though that Caged Bird is a type of protest song, and can be placed in a long, proud history of struggles for emancipation and equality. Angelou neatly supposes that freedom to explore the world is the key to unlocking a person’s full potential. Look back at the first stanza and you can see that, by the time his travels are done, the free bird will have the daring and courage to claim the sky. More, she suggests that freedom is an inheritance that cannot be denied: even a bird caged its entire life – or a child born into segregation or slavery – can feel their basic freedoms denied as things unknown but longed for still. Thanks to that song-like refrain, the last word of the poem is freedom, leaving us with a more optimistic ending than we might otherwise have imagined. Look even more closely and you’ll notice that the poetry seems to ‘break out’ of the shackles of iambic rhythm in the last couple of words. The prevailing de-dum rhythm suddenly reverses itself to dum-de (this is known as a trochaic reversal); so read the last few lines out loud and you’ll hear how freedom actually ends in an unstressed syllable:

/sīngs of /frēedom.

Angelou lived through so many setbacks to the civil rights movement in the US: the assassinations of Dr Martin Luther King and Malcolm X; the bombing of a black church congregation in Birmingham, Alabama; the Watts Riots. But she didn’t get knocked back for long: she never gave up singing – writing – for freedom.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Caged Skylark by Gerard Manley Hopkins

In this poem Hopkins uses one of his favourite motifs – a bird trapped in a cage – as a metaphor for the human condition. Trapped in our bodies, our appreciation of the world is limited; until we die and ascend to heaven.

- Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

This poem hits like a punch. And even when she’s down and out, Maya Angelou won’t give up. One of her most celebrated works.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Caged Bird at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on contrast and juxtaposition

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… Discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Caged Bird? What ideas did the poem suggest to you? What other poems would you recommend readers who like Maya Angelou’s poem? Why not leave a comment, start a discussion or let us know what you think below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Hi there,

I was just scrolling, and fell in love with your analysis. I’m inspired.

Thanks.

Hi Adu,

Thank you for your comment, I’m so glad you like the breakdown of this poem. The caged bird’s life is so bleak – but there’s a note of hope at the end.

Hi,

I enjoyed your detailed analysis of the form and structure of the poem.

When I began to research the poem, I felt confused by the overwhelming opinion that the poem is written in free verse, with no rhyme or rhythm at all. The infrequent rhymes/half-rhyme/internal rhymes were occasionally mentioned but yours is the only analysis I have found which alludes to the iambic rhythm. I agree with your take, which you detail so clearly. Thank you.

Hi Emma,

I wonder if, because the poem is largely unrhymed, some commentators are suggesting it’s written in free verse? The patterns of rhythm suggest otherwise though. As you say, meter plays a tremendous role here, organising the lives of the birds into a pattern and more or less evenly timing the lines.

Yes, I agree that it plays an important role. You describe it perfectly. It was wonderful to see Amanda Gorman wearing the bird cage ring yesterday. It inspired me to read the poem again!

Wonderful job! looking forward for more

I LOVED YOUR ANALYSIS. I have an exam tomorrow, too many things to study. I don’t have time to read such long analysis for each chapter, but I’ll surely be back once my exams are over. I plan on reading more analysises by you.

I hope your exam went well and happy that the analyses are useful for you. Best of luck!

I have been teaching literature for a while and only now did I come across your detailed analysis. Thank you so much for sharing it. It is quite unique as well; not many Google search results include a resource of such quality.

Hi Paula, thank you so much for your kind words. I’m happy to share, and hoping my analysis gels with the way others read the poems as well.