Edna St. Vincent Millay is confronted with mortality in this exquisitely crafted little poem.

“There was no other voice like hers… It was the sound of the ax on fresh wood.”

Louis Untermeyer, Poet, Critic and Editor

Death is taboo, a subject kept away from polite conversation. People can be reluctant to talk about death, or even say the word aloud if the circumstance are sensitive. Often death is euphemised with words such as ‘passed away’, ‘left us’, ‘no longer with us’ and the like: in this poem the speaker’s first reaction to witnessing the death of an animal is to call it a strange thing. This is a kind of verbal camouflage. Just as scenes of dying on television are censored, softened or restricted to later times, so too do these words conceal the reality of death. Millay’s poem helps strip away the camouflage and present us a shocking, vivid scene of an animal dying. Facing this scene forces the speaker, and the reader, to think more directly about death and accept the reality that death is an inevitable part of life.

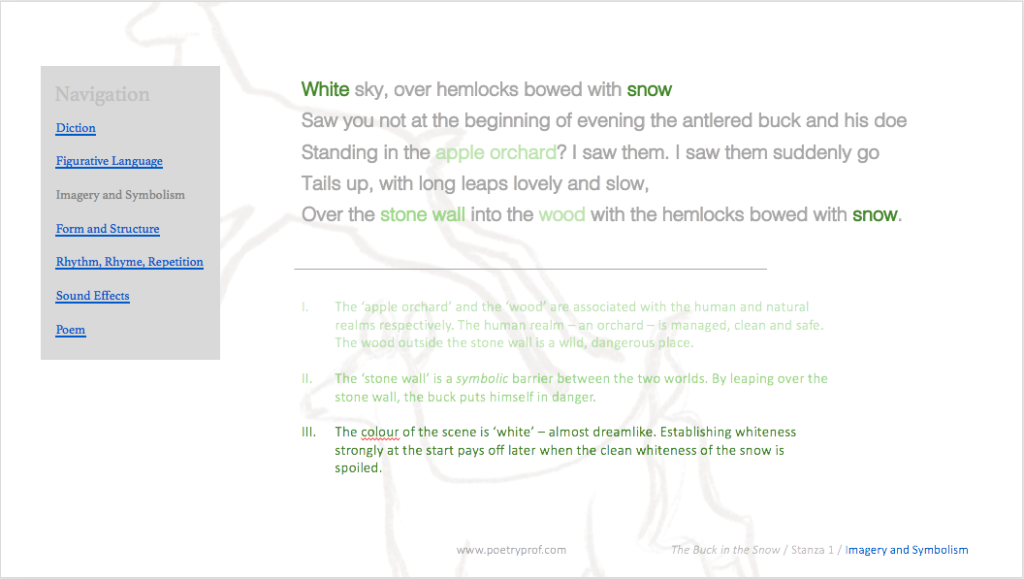

White sky, over the hemlocks bowed with snow,

Saw you not at the beginning of evening the antlered buck and his doe

Standing in the apple orchard? I saw them. I saw them suddenly go,

Tails up, with long leaps lovely and slow,

Over the stone wall into the wood with hemlocks bowed with snow.

Now lies he here, his wild blood scalding the snow.

How strange a thing is death, bringing to his knees, bringing to his antlers,

The buck in the snow.

How strange a thing, – a mile away by now, it may be,

Under the heavy hemlocks that as the moments pass

Shift their loads a little, letting fall a feather of snow –

Life, looking out attentive from the eyes of the doe.

Death was ever-present in Millay’s thoughts. It might be said she had a bit of an obsession with this topic. During her life she suffered from neurosis, intermittent problems with alcohol and medications, and even nervous breakdowns. Despite being married once, her love life consisted of a good number of affairs and she found it hard to maintain monogamous relationships. Perhaps the story of how one particular relationship ended gives us an insight into why. In 1920 she had an affair with fellow poet Arthur Ficke, whom she met while he was on military service. Although very brief, their feelings must have been profound as each would later write several sonnets about the other. Millay always believed their love could not endure death: she even wrote the line, ‘And you as well must die, beloved dust.’ This anecdote seems relevant in light of The Buck in the Snow, which describes a close encounter with the death of an animal. After contemplation of this strange scene, Millay’s speaker seems more conscious than ever of her own mortality: her brush with death has given her a candid reminder of the brevity of her own life.

To begin with, these concerns are not apparent. The poem is split into three distinct parts and she actually encounters the buck twice: the first time it is running through an apple orchard with its mate, full of life. The poem takes a sudden lurch between stanzas one and two when we see the buck again, this time lying bleeding in the snow. Her – and our – delight is immediately, and quite cruelly, tempered by the shock of the second meeting. In the third part of the poem the speaker contemplates the scene she has witnessed, her thoughts tinged with sudden melancholy at the reminder of the mortality of all living things.

I really like the way this poem is addressed to an unseen listener. It’s easy to imagine Millay turning to a companion, asking saw you not…? I saw them… wanting to talk about and affirm what she has seen. It helps us feel something of the delight that the encounter with the buck evoked and creates an intimacy between the reader and the speaker, as if she is speaking directly to us. There’s excitement in her descriptions of the buck and his mate, Tails up, with long leaps lovely and slow. Alliteration helps us feels her admiration, the liquid L sounds combining with assonant O to create the liveliness of the deer and their slow, graceful leaps. There’s a sense of reverence in her poem too. Millay was not a religious person, but her first stanza presents religious imagery: white sky seems heavenly; hemlocks bowed makes me imagine a congregation of worshippers, heads bowed in prayer. Repetition of this image at the end of the stanza signals it is more than simple description.

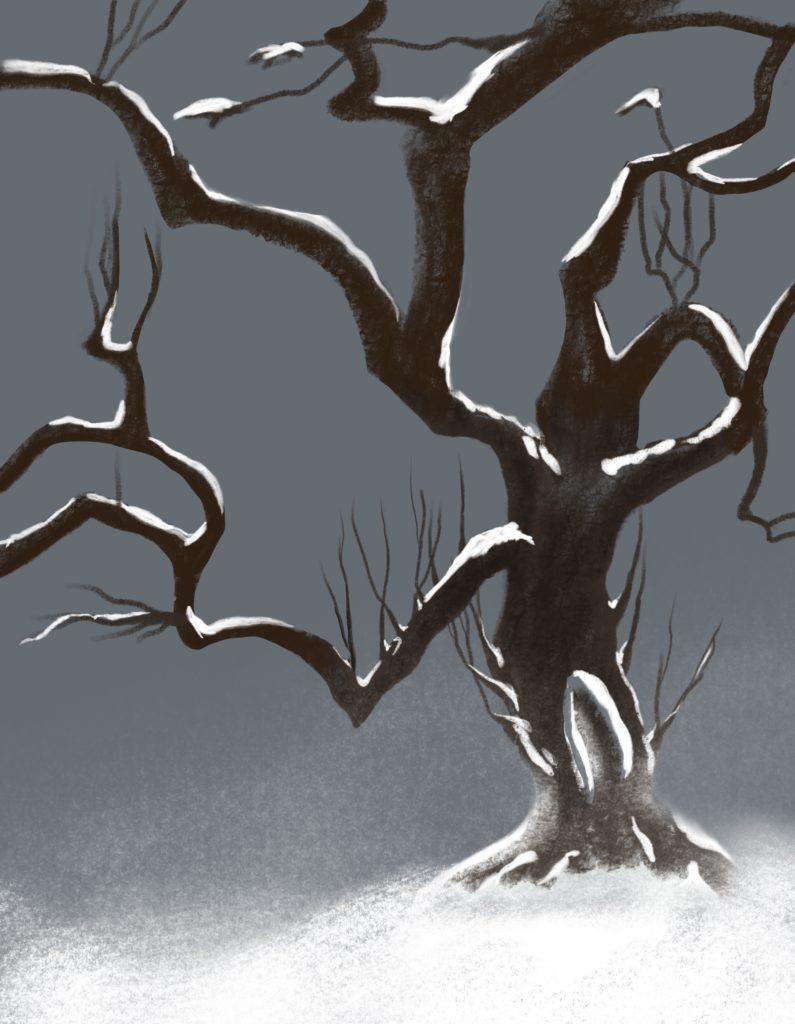

Central to this is an understanding of the symbolism of the hemlocks bowed with snow. Growing up in New England, Millay would have been familiar with hemlock trees (they are the state tree of Pennsylvania) and certainly known that they are a traditional symbol of healing and protection. She re-appropriates this traditional symbolism – in her poem, the trees are a silent audience witnessing the death of the buck. Look how in the third stanza they shift a little, letting fall a feather of snow. The personification reminds me of mourners at a funeral, symbolically casting earth into a freshly dug grave. When the deer jump over the stone wall they seem to vanish into the hemlock trees. But instead of protecting them, the trees silently watch as death claims the buck. Actually, this association is not entirely Millay’s own. One form of hemlock bark is poisonous, and was used in Ancient Greece as a method of execution: the philosopher Socrates was forced to drink hemlock after his ideas were deemed impious. It’s an irony that becomes more apparent once the excitement of stanza 1 turns to sadness later in the poem.

As well as excitement, though, there’s something oddly formal about the way the lines are written. Look again at saw you not at the beginning of the evening the antlered buck and his doe? Spontaneous speech would be more like ‘Did you see…?’ You can see the same thing again later: Now lies he here instead of ‘He lies here now’; again in the third stanza: how strange a thing is death and a mile away by now, it may be. Fans of Star Wars’ Yoda will recognize this technique: Millay is using inverted syntax by which the natural word order is reversed. The effect it creates is a bit peculiar; it certainly adds to that reverent tone. Mostly though, it gives the impression that the poem comes after a period of contemplation. It indicates controlled emotion rather than an outpouring of feeling.

The second stanza is a real shock. It sits starkly, a single line surrounded by white space, like the buck’s blood splashed vividly against the white snow. Scalded intensifies the image of hot, fresh blood steaming in the cold, and suggests pain too. The oppositions of life and death are juxtaposed: wild blood scalding represents the heat of life where the snow is symbolic of death. Don’t underestimate Millay’s brilliant use of ellipsis here. We jump from the first stanza to the second, with nothing to fill the blanks or prepare us for the sudden change. Was the buck shot? Did it fall? Was it hit by a car? The only clue appears later in the line over a mile away: is the speaker in a vehicle of some kind? Perhaps the buck leapt unknowingly into the road… Whatever happened in that gap of white space, the sudden lurch from playful delight to shock reminds us that death might be just a moment away. The point is driven home by the switch from past to present tense.

Actually, there are many such juxtapositions, all working to mirror the ultimate opposition of life and death (seen in stanza 3). Look how, to begin with, the animals are running in an apple orchard. Later they leap over a stone wall, a kind of symbolic barrier between the illusory safety of the human world (orchards are managed carefully by people) and the wood, a wild world governed by the forces of nature. If the buck and his doe (in particular his hot, wild blood and her eyes) are symbolic of life, then snow is an obvious symbol for death; these are the only two elements present in all three parts of the poem (plus the title), a reminder that death is an ever-present companion to life. You can see juxtapositions too in the language of the poem: for instance, quick, light consonant sounds sit next to long, low vowels; tails up is opposed by now lies; standing is reflected by falls.

Afterwards, the speaker continues on her journey, but now her thoughts dwell on what she has just witnessed. She has had a little glimpse into the ‘wild’ world, where the barrier between life and death is more thinly camouflaged. She becomes contemplative and melancholy: you can feel her replaying the scene when she says how strange a thing, and bringing to, both repeated twice to create the impression of her turning it over and over in her mind. Look how the sounds of the poem have shifted from the lively quick L alliteration of stanza one to slow W and nasal sounds such as those in a mile away by now it may be. Nasal is great at suggesting suppressed emotion and this is precisely what is happening as the speaker works through the mounting realisations she’s having about life and death. In the following line heavy hemlocks is easy to pick out, the aspirant H sounds mimic exhalation.

If the descriptions of stanza 1 conjured a strong sense of place, stanza 3 creates a sense that time first slows… then suddenly speeds up again. It’s like she gets caught in the moment, replaying the scene on a loop in her mind, then has a sudden realisation that her life – like that of the buck – is also leaping towards its end. Look at how the punctuation helps to create this impression. There’s a long pause in line 9, created by a hyphen, in which time seems to stretch out as she contemplates the significance of the strange thing. Then the poem suddenly accelerates again, as if time rushes to catch up with itself: a mile away by now, the moments pass, shifting, letting fall all suggest movement. Short phrases one after the other, enjambment, and the second hyphen work to create this sudden sense of time passing as well.

The speaker, either consciously or subconsciously, has received a reminder of her own mortality. And, as is so often the case in works exploring this theme, life suddenly seems much more precious when juxtaposed with the knowledge of death. Look how the final lines of the poem reassert the presence of life; implicitly through the return of that lively, quick L sound (loads a little, letting fall a feather of snow – life looking); and explicitly, looking out defiantly from the attentive eyes of the doe. There is something poignant and tragic in the way the doe helplessly watches her mate; it’s an echo of the poignancy the speaker feels about her own life now she’s had the shocking, vivid reminder that all things – herself included, and you and me – will one day die.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- An Ancient Gesture by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Millay explores mortality for us again in this poem. Penelope (the wife of Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey) gently wipes her eye, a gesture that exposes raw grief at the loss of a loved one.

- The Bull Moose by Alden Nowlan

This powerful and moving poem shows us the last moments of a majestic moose as he stumbles out of the mountains like an ancient king come to die amongst his people. The effect on the speaker and those watching, like Millay’s buck in the snow, is profound.

- To Death by Anna Akhmatova

Translated from Belarusian, this poem imagines the ways death can suddenly come. Perhaps because of where she lives, mortality seems a lot closer in this poem. “I could care less,” she tells us, ambiguously.

- Traveling Through the Dark by William Stafford

This amazing poem tells of a driver who comes across a deer dead in the road. He cannot swerve around, so gets out of his car to investigate. What he finds evokes similar questions to those posed by Millay’s distraught speaker.

Additional Resources

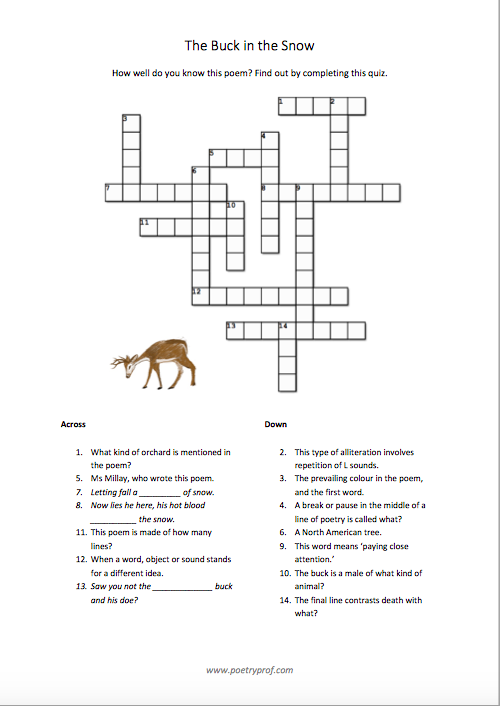

If you are teaching or studying The Buck in the Snow at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to download a bespoke study bundle for this poem. Costing just £2, the bundle includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on different kinds of symbolism in Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap activity or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

How did you feel when reading Millay’s poem? Were you shocked by the second stanza? What do you make of the speaker’s thoughts and feelings in the final verse? Why not leave a comment, share an opinion, or start a discussion in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

this was such an amazing breakdown of the poem

Hi Nicole,

Thank you for your comment – I’m glad you enjoyed the analysis. I find the whole scene in the poem quite haunting, the way those hemlock trees stand round like silent witnesses. It’s beautiful, but cold at the same time.

Thank you so much!

Hey that a good analyzes l liked that one pls send more other poem has well

Hi,

Thank you for your kind comment. You can find more poems on the blog – use the search function at the top of the page or browse the menu screen.

Thank you for this fantastic analysis, prof! You have saved my life! Love u 😽

Me too! Love u prof😘😘 ur such a king

Coincidence that your name is dog! 😂😂😂. Lol! WAP

Meow😂❤️‼️‼️ Animal tings😊😏😉✌️

It’s such an elaborate analysis!

I’m impressed by how creatively you blend the poetic devices into your breakdown. Some of these are so insightful I’d never have pulled them off as easily as you did. Thank you 😍

Hi Marie – thank you for your message. I’m glad my analysis is insightful for you, and even happier that I give the impression it comes off ‘easily’. That’s definitely not always the case!