Immerse yourself in Lauris Edmond’s beautiful images of sun and spray.

“Her poetry conveys… a strength in facing the dark side of life”

Janet Wilson (from Edmond’s obituary)

Once in a while a poem comes along that strikes with the force of falling water. For me, reading today’s poem, Waterfall, was as invigorating as immersing myself in cool water on a hot day. The poem’s central concern is ageing and how the passing of time enhances (or distorts) memory, how it strengthens (and erodes) the bonds between one person and another; how it transforms the shape of love – from intimacy to kindness and back to passion again – in the most unexpected ways.

I do not ask for youth, nor for delay in the rising of time’s irreversible river that takes the jewelled arc of the waterfall in which I glimpse, minute by glinting minute, all that I have and all I am always losing as sunlight lights each drop fast, fast falling. I do not dream that you, young again, Might come to me darkly in love’s green darkness Where the dust of the bracken spices the air Moss, crushed, gives out an astringent sweetness and water holds our reflections motionless, as if for ever. It is enough now to come into a room and find the kindness we have for each other – calling it love – in eyes that are shrewd but trustful still, face chastened by years of careful judgement; to sit in the afternoons in mild conversation, without nostalgia. But when you leave me, with your jauntiness sinewed by resolution more than strength – suddenly then I love you with a quick intensity, remembering that water, however luminous and grand, falls fast and only once to the dark pool below.

Issues with time and delay seemed to have dogged Lauris Edmond through her life; she postponed her own creative studies in Wellington (New Zealand) to accompany her husband as he embarked on his own career as a headmaster; she was 51 before her first collection of poetry was published, and felt that she came late to her poetic calling; she died suddenly and before her time in 2000. In another poem, In Position, Lauris wrote, ‘I want to tell you about time, how strangely it behaves when you haven’t got much of it left.’ Here, time doesn’t ‘behave strangely’ so much as rush past, flowing swiftly and falling suddenly towards a dark pool waiting at the end of the waterfall.

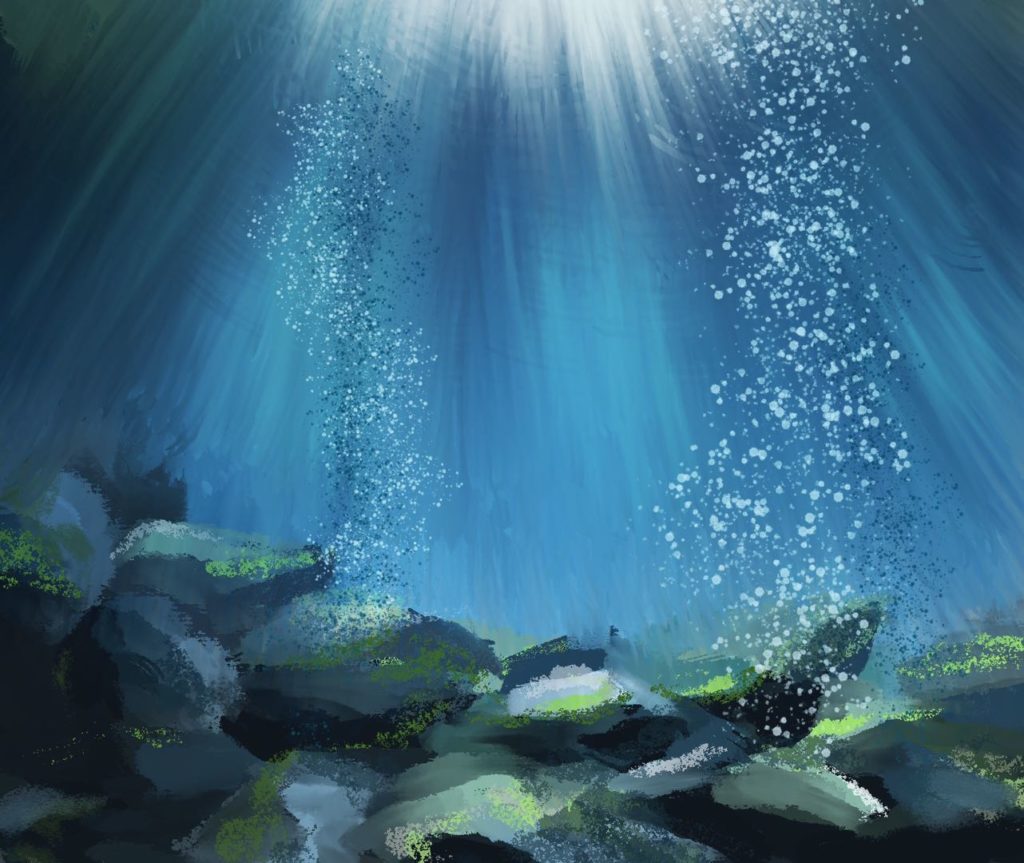

Reading this poem really is to stand beside a waterfall, feeling the spray splash your face, hearing the deafening roar of rushing water fill your ears. At points, Edmond almost creates a touch of vertigo, as if the reader is caught up in the tug and flow of the irreversible river cascading over the cliff face. In order to achieve this effect, she masterfully employs several elements of poetic form which combine to whisk you along with the river’s current, over the edge of that precipitous drop. Most obviously, each stanza is one long sentence and Edmond avoids using any kind of end-stopping (punctuation at the ends of lines of poetry). In fact, she uses as little punctuation as possible (only using commas to link clauses) preferring to let the lines of poetry flow uninterrupted one into another. This technique is called enjambment and it evokes the feeling and sensation of water flowing ceaselessly down the rock face. A strong sense of speed and downward motion is reinforced by repetition, especially in the case of repeated words (minute by minute… fast, fast falling) and words whose parts seem to collide against each other like water droplets coming together and smashing apart in an explosion of spray: sunlight/lights; you/young; darkly/darkness; moss/motionless.

The poem is rhythmically unpredictable, opening with a line of perfect iambic pentameter but immediately losing the reassuring regularity of meter, with Edmond happy to let her words cascade down the page as they will, like water bouncing and rebounding randomly on its way down. Something she is careful to do though, is, more often than not, end her lines on an unstressed syllable. Here’s the first stanza with accents marked and the final downbeats underlined so you can see how often this happens:

I dō/ not āsk/ for yōuth,/ nor fōr/ delāy/ in the /rīsing of /tīme’s irre /sīstible /rīver that tākes the jēwelled ārc of the wāterfall in which I glīmpse, mīnute by glīnting mīnute āll that I hāve and āll that I am ālways lōsing as sūn light līghts each drōp fāst, fāst fālling.

Lines composed so that they end on a ‘downbeat’, or unstressed syllable, are lines written in falling rhythm. It should come as no surprise that a poem called Waterfall employs this effect; in combination with enjambment and repetition, it recreates the direction and momentum of water pulled ‘downwards’ by gravity. Fans of unusual metrical pattens might also be pleased to find four consecutive stressed beats in the final line – drōp fāst, fāst fālling – as if the downward pull becomes more and more irresistible.

Closely contemplate whatever image of a waterfall you can conjure in your imagination and you should be able to hear a tremendous thundering, rushing sound. This auditory experience is a major part of the image, so Edmonds fills her poem with all sorts of alliteration (words that begin with the same letter or sound) consonance (repetition of sounds within words) and assonance (repeated vowel sounds) which combine to recreate this sonic boom. The combination of assonance and softer consonants can achieve an effect called euphony, by which sounds blend so harmoniously they become almost like musical chords. The first lines of the poem achieve this effect through the blending of Y, I, R and S: I do not ask for youth, nor for delay in the rising of time’s irreversible river. The letter R in the second line is particularly noteworthy: R (along with W and L) is part of a category of alliteration called liquid, which is perfect for creating a sensation of fluid, watery movement, such as the rush of the irreversible river.

You’ll hear euphony at the start of the second stanza too: I do not dream that you, young again, might come to me darkly in love’s green darkness blends assonant sounds such as O, Y and long E with nasal M and N. Although euphony is made with vowels and softer consonants, Edmonds studs her lines with occasional hard alliterations, recreating a variety of percussive sounds that echo above the background noise of the falling water: hard D (do not… delay, do not dream, darkly/darkness) is one example; guttural G and K sounds (ask, come to me darkly in love’s green darkness) is another. Imagine water striking rocky outcrops, loosened stones falling, or even noises like bird calls from the surrounding forest to get an idea of the depth of experience reading this poem can conjure up.

The waterfall is, of course, the poem’s most important symbol. It stands for both the beauty of life and the swift passing of time. In fact, the poem argues that, like a glorious sunset or a delicate flower, some things are beautiful precisely because they are so transient. In the first stanza, the fluid and transient nature of life is evident in contrasting words such as rising / falling and have / losing. As becomes evident in the third stanza, the poem is written from the perspective of an older person looking back over their life determined to have no regrets, despite how quickly life’s pleasures seemed to rush by. That irreversible river, as well as being a metaphor for life, is also a metaphor for time; synonyms for the word irreversible could be ‘irresistible’ or ‘remorseless.’ Look how the very first words of the poem introduce the concept of time into the poem: youth, delay, time, then later in the stanza, minute by minute and fast, fast falling. Even words like glimpse suggest something passing by at speed – here one moment and out of sight the next. As one gets older, the knowledge that more time is behind than ahead becomes more acute, and the looming awareness of the dark pool waiting at the bottom of the waterfall more and more powerful. That pool is a direct metaphor for death; once the drop of water representing Edmonds’ life hits the dark pool at the bottom of the waterfall, her time has run out and she will die. What might surprise you about Edmonds’ stance is she doesn’t waste time feeling sorry that she’s nearer the bottom of the waterfall than the top – instead she accepts that an intrinsic part of the human condition is being subject to the passing of time. That’s why she begins her poem by saying I do not ask for youth, nor for delay where her unwillingness to devalue the precious moments of her life is conveyed through negation using not and nor; she doesn’t want to diminish the precious moments of her life by trying to hold onto them too tightly.

When considering the symbolic function of the waterfall, you can make a distinction between the movement of the water (which represents the swift passage of time) and the millions and billions of drops of water that make up a river, representing individual lives. When Edmonds writes the sunlight lights each drop she reminds us of how light refracts when passing through water, splitting spectacularly into all the colours of a rainbow that seems to hang in the waterfall’s haze; through this interaction, light imagery renders the scene exquisitely beautiful and conveys the idea that each and every drop has its moment to shine. Similarly, the word jewelled suggests that the momentary sparkling of each drop of water is something precious to be cherished. Later, in stanza four, the words luminous and grand are used to describe water, but can also be understood as the poet looking back over her life and finding it both astonishing and beautiful. Despite the inherent sadness of growing old there’s no sense that the speaker regrets any of her choices; rather, she seems captivated by memories of the life she’s lived and contrasts throughout the poem (luminous / dark pool; green darkness) serve to make the bright moments sparkle even more brightly.

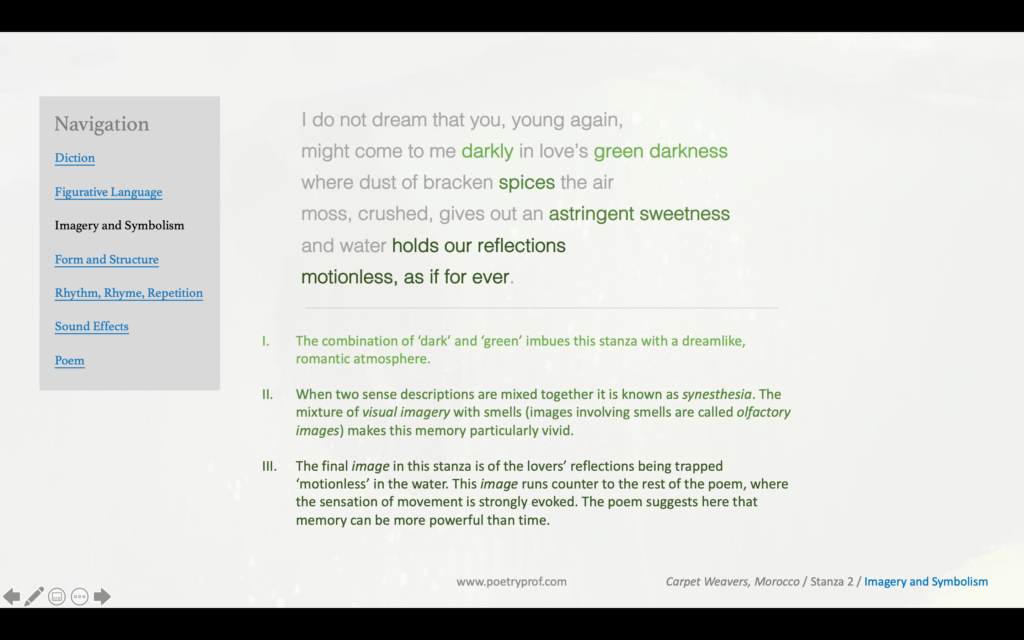

Where the first stanza introduced universal themes like the passing of time, the second stanza is intensely personal; notice how it suddenly addresses a specific person using the word you. Edmond married her husband Trevor in 1945 after he returned from serving in the war. In spite of some famous difficulties – Lauris had to subsume her creative ambitions to his career and she finally decided to move to Wellington to study an MA while he worked as a headteacher far away; she began an affair with her professor, the first of several she would have in her life; their daughter Rachel would commit suicide aged 21 – their marriage ultimately lasted their whole lives. The sinewed man in stanzas three and four is certainly Trevor Edmond, who, even after all their troubles, remained Lauris’ companion until her death in 2000. While it’s possible that the man in stanza two is one of her lovers, I prefer to think that this man is also Trevor Edmond, transformed by memory into the young man he was when they first met. The scene has suggestive erotic undertones; come to me can be read romantically, or even breathlessly; the moss has been crushed as if two people used it as a blanket to lay down on; sweetness conveys the intense pleasure of this dream-memory. At stanza’s end the lovers’ reflections will be caught in the water’s magic mirror, freezing them in time as if forever. It’s a brilliant counterpoint to the rapid tumble of the rest of the poem; instead stanza two ends gently with a vivid image of motionlessness and a moment of stillness. In doing so, Edmonds suggests that memory can be used as an antidote to the inevitable and relentless passing of time, trapping vivid moments outside of time and preserving them forever.

Light imagery and contrast are important components of the mysterious second stanza, which plays out like a fantastical dream sequence. I suspect the second stanza is a vivid memory, or perhaps half-memory, half-fantasy; a real-life encounter transported to the fantasy setting of a forested grotto or secret cave hidden behind the waterfall’s curtain. The contrast between green (moss also backdrops the scene in spongy green) and darkness, repeated as darkly, creates a strong visual effect as if the memory/dream/fantasy is filtered through dappled light, deepening the sense of mystery. It’s a brilliant way of suggesting the distorting effect of time on memory and the way we romanticise the past; over time, our memories turn sepia-coloured and we view them as if through a refractive curtain of water. When writers mix different sensory descriptions it’s known as synaesthesia and Edmonds blends the shadowy colours of the scene with rich, sharp smells (the dust of bracken spices the air and the words astringent sweetness appeal to the sense of smell; images made of smells are technically called olfactory images) which intensify this woozy, heady, dreamy impression. Astringent means ‘bitter’ or ‘acidic’ and this word pushes against sweetness to form an oxymoron – Edmond implies that memories of a romantic, passionate tryst are bittersweet now she lives in a quieter, passionless present.

Just as a waterfall is always flowing and changing, the poem’s images twist and turn too. As already noted, the third stanza comes back to the present (it is enough now) and, temporarily at least, moves away from the waterfall image. In place of secret coves and romantic clinches comes a more prosaic realisation of love. Edmonds admits that time changes love, much as a waterfall erodes a rock face, flattening it and making it less dramatic. You’ll notice a sudden contrast in diction where words such as enough, come into a room, sit, careful and mild conversation are simpler, restrained and reserved. Imagine the feeling of rafting through wild river rapids and to then emerge into a stretch of flat, calm water. Edmond admits that what they are calling love is something more akin to kindness, where two people who are so familiar (trustful) recognise a mutual need for companionship. Several words allude to tension in the past and we have already discussed Edmond’s infidelities: shrewd, judgment, careful, chastened hint at turmoil endured and lessons learned. As a result, Edmond doesn’t mind living in the calmer, quieter present day. She might be happy to indulge in the odd romantic memory, but she tells us the two live together now without nostalgia. The motif of water throughout the poem (river, drops, waterfall and water) brings to mind the phrase ‘water under the bridge,’ as if both husband and wife prefer to leave their troubles in the past, where they belong.

Just as we think, though, that Edmond has made peace with the reality of growing old and consigned passion to the past, the poem changes course once more, and the speaker betrays the fact that she is still capable of an intensity of feeling and an uncontrollable desire to love. Where both stanzas two and three argued that we can oppose the passing of time (through either memory or by deciding to focus on the pleasures of the present rather than dwell in nostalgia), the final stanza reasserts the power of time through words like quick, suddenly, falls fast and only once. This sudden reversal follows the poetic tradition of the turn, by which the exploration of a given theme involves some sort of change in direction or shift in perspective. You can find these shifts in many poems, and they are usually marked by a connective such as ‘yet’, ‘but’, ‘thus’, ‘and so’. Edmond gives us But when you leave me at the start of the fourth stanza, and emphasises her turn-about with – and suddenly in the third line. Images (sinewed provides a visual image of an aged body sloughed of muscle and physical strength) and the phrase when you leave me reminds us that both her and her husband are nearing that dark pool at the end of their lives.

Whilst now he’s just getting up to leave the room, the knowledge that one day he will ‘leave’ her for the last time simmers, unavoidably, underneath the poem as if just beneath the surface of a dark pool.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- In Position by Lauris Edmond

Another beautiful poem about time and growing old. You’ll recognise plenty of ideas from Waterfall; the image of a river of time; the idea that growing old isn’t sad at all.

- I Have a Rendezvous with Death by Alan Seeger

Like Edmond, Seeger is aware of his approaching death. The context of this poem, though, is he’s heading back to the front in the First World War, and knows he is not likely to return (Seeger was killed in 1916).

- The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes

One of the most famous poems about bodies of water anywhere, Hughes’ poem begins with the immortal line, ‘I’ve known rivers.’ His poem is also about time, spanning the millennia from the beginnings of human civilisation to the year he was writing.

- Waterfall at Lu-Shan by Li Bai

Chinese poet Li Bai (born in 702) of the Tang Dynasty spent most of his life travelling and writing. He is famous for producing exquisite images. This short and much-recited poem was composed after gazing upon the waterfall at Lu Mountain (Lushan in Chinese).

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Waterfall at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring enjambment and caesura in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy our take on Lauris Edmond’s Waterfall? Did the poem leave you as breathless as it did me? What kinds of images did stanza two conjure in your mind? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

On my copy of the poem (Songs of Ourselves Vol.2), the rising river in stanza one is described as “irreversible” instead of “irresistible”. Other poems I found online also uses “irreversible”.

You’re quite right! Thank you so much for the keen-eyed spot. All fixed now.

I’m glad! To be honest I noticed it because in the poem bundle the crossword didn’t make sense due to the irresistible/irreversible thing.

Thanks! Appreciate the site a lot 🙂

Sera x

Thankyou for your analysis, I love how you phrase your observations!

Hi Zara,

Thank you for your kind comment. You can probably tell that I was very taken by Waterfall; it’s one of those poems that brings goosebumps to the skin. I hope you enjoy the other posts on the site as well.

this is quite help-full thank soo much i really appreciate

You’re welcome, David. This is one of my favourite poems to have covered – I hope you like it too.