Join Alexander Pope on a metaphysical journey of discovery… that will last a lifetime.

“[It is] difficult to know which part to prefer, when all is equally beautiful and noble.”

Weekly Miscellany comments on the poetry of Alexander Pope

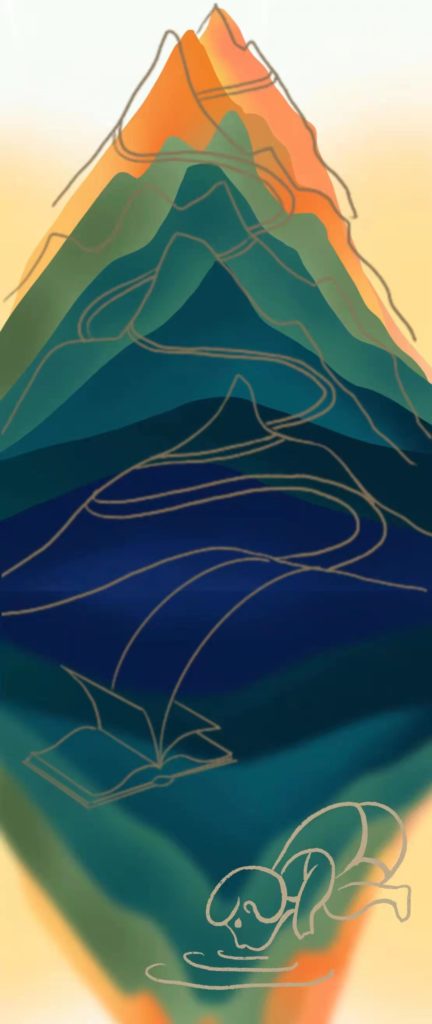

Alexander Pope spent his childhood in Windsor forest and, from an early age, gained a keen appreciation for nature. Later in his life he lived in a property by the River Thames in London where he cultivated his own garden that he opened for visitors. In today’s poem, written in 1709, we can see this love of the natural world through his shaping of elements of the landscape into an extended metaphor for knowledge. This landscape is vast and mountainous: the Alps, Europe’s largest mountain range are a prominent feature, as are hills, vales, an endless sky and eternal snows. Compared to this vast landscape, people are almost insignificant. Their role in the poem is to act as explorers who set off on a journey of discovery, trying to conquer the highest mountains by ascending to the summit; we tempt the heights of Arts… the towering Alps we try… Finally, despite being almost exhausted by his efforts, the explorer realises that his journey has barely begun; the mountain vista stretches ahead, unbroken, into the distance:

A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring: There shallow drafts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again. Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts, In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts; While from the bounded level of our mind Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind, But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise New distant scenes of endless science rise! So pleased at first the towering Alps we try, Mount o’er the vales and seem to tread the sky; The eternal snows appear already past, And the first clouds and mountains seem the last: But those attained we tremble to survey The growing labours of the lengthened way; The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes, Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise.

A poem’s central idea, often developed into an extended metaphor, is known as a conceit. Unlocking the first couplet should provide you the key to Pope’s conceit in An Essay on Criticism. Pope begins with a warning that:

A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring:

The Pierian Spring is an important place in Greek Mythology, the source of a river of knowledge that was associated with the nine ancient Muses, themselves a metaphor for artistic inspiration. In this poem, it’s part of the landscape that functions as an extended metaphor for learning. It might seem strange that Pope begins by giving his readers a warning to taste not the waters of this river. However, it’s important to realise that Pope isn’t saying not to drink from the well of knowledge at all. He tells us to drink deep, emphasising his instruction with both alliterative D and using the imperative tense (where the verb is placed at the beginning of the line or phrase). To Pope’s mind, learning is seductive and intoxicating. Once you set out on the journey of learning, or take even a tiny sip from the wellspring of knowledge, you won’t be able to resist the temptation to learn more. Therefore, he suggests that you either prepare to immerse yourself completely in the Pierian Spring, or don’t drink at all.

Once you’ve discovered the connotations of Pierian Spring, the rest of the poem can be read as a warning (or criticism) of anyone who is rash enough not to follow Pope’s instruction. Should you venture unprepared into the unknown, you must be clear about your limitations. As a spring is the starting point of a river, so too is it the starting point of Pope’s extended metaphor. From here, the reader sets out on a journey into an imposing mountainous landscape that, while initially appearing it can be ‘climbed’ or conquered, actually keeps expanding into an endless vista. No matter how far the explorer climbs, the top of the mountain never gets any nearer. Heights, lengthening way, increasing prospect and, most telling of all, eternal snows conjure the visual image of the landscape metaphysically stretching out in front of our weary eyes. Individual people are tiny and easily lost in this ever-shifting world. Pope creates a contrast between the boundless landscape and the bounded limits of human perception. At the last, the human explorer is tired by his efforts to conquer these mountains of knowledge – but the poem ends by revealing that he’d barely even gotten started on his journey: Hills peep o’er hills; Alps upon Alps arise.

Before we get too much further into the discussion of Pope’s ‘essay’, it might be helpful to place these lines in context. Despite the way they seem to be a complete poem in themselves, they are actually part of a much longer poem which stretches to three parts and a total of 744 lines! The eighteen-line extract you’ve read constitutes the second verse of Part 2 and it may help you to know that, in the first verse, Pope singled out pride as the characteristic that would eventually lead to the downfall of his explorer. Here are four lines from earlier in the Essay:

Of all the causes which conspire to blind Man's erring judgment, and misguide the mind, What the weak head with strongest bias rules, Is pride, the never-failing vice of fools.

In this short sample, you can see the names Pope calls people who rush off on foolhardy adventures without taking the time to properly prepare: blind man, weak head and fools! Younger readers might not enjoy this interpretation, but Pope finds the overconfidence of young people most problematic, associating youth with a kind of recklessness that, in hindsight, is misplaced.

You may argue that qualities such as fearless and passionate (fired) seem like compliments; but I detect a note of criticism in Pope’s words; he suggests that young people confuse emotion with clear thinking and they are too eager to plunge into the unknown. There’s an emphasis on speed and rashness (pleased at first; at first sight) that cannot last, like a novice marathon runner who goes sprinting out of the blocks while older, more wily competitors know to save themselves for the challenges ahead. While the young explorer does encounter some early success (implied by words like mount, more advanced, attained and, more significantly by an image: tread the sky), the race is longer than the runner thought and inevitably the pace must sag. Later in the poem, positive diction disappears and words like trembling, growing labours, and tired take over as the true scale of the challenge becomes apparent. Sharp-eyed readers will already have noticed that the image of ‘treading the sky’ was in fact a simile: seem to tread the sky. Subtly, Pope’s use of a simile implies that any success the explorer thought he’d achieved wasn’t actually real.

The implication that over-enthusiasm can cloud good judgment can be traced through diction to do with looking and seeing: at first sight, short views, see, behold, appear, survey, eyes and peep pepper the poem and convey the poet’s belief that, to our detriment, we can be short-sighted and tunnel-visioned. The eighth line of the poem is entirely concerned with this idea: short views we take, nor see the lengths behind paints a picture of a young explorer who only looks in one direction – eyes fixed straight ahead – and so misses the bigger picture.

While the poem is certainly didactic (it’s trying to impart a lesson), Pope’s tone of voice is not too condescending or stand-offish because he includes himself in his criticism as well. Throughout the poem the words us, we and our soften his accusations so there’s never a ‘them-and-us’ divide between young and old. In fact, Pope was only 21 years old when he finished his Essay on Criticism, so use your mind’s ear to imagine him speaking ruefully from experience, rather than as a nagging or pestering adult complaining about ‘young people today.’ The line Fired at first sight by what the Muse imparts is revealing in this regard. Alluding to the nine Muses of Greek mythology, this line personifies poetic inspiration, so in one sense the extended metaphor of trying to conquer an unknowable landscape represents his own experiences of writing poetry. ‘Meta-poems’ (poems about the writing of poems) actually have a name: ars poetica. Pope implies that rushing off on a path of artistic endeavour without realising the true extent of the commitment that entails is a mistake that he himself has made in his own attempts at writing.

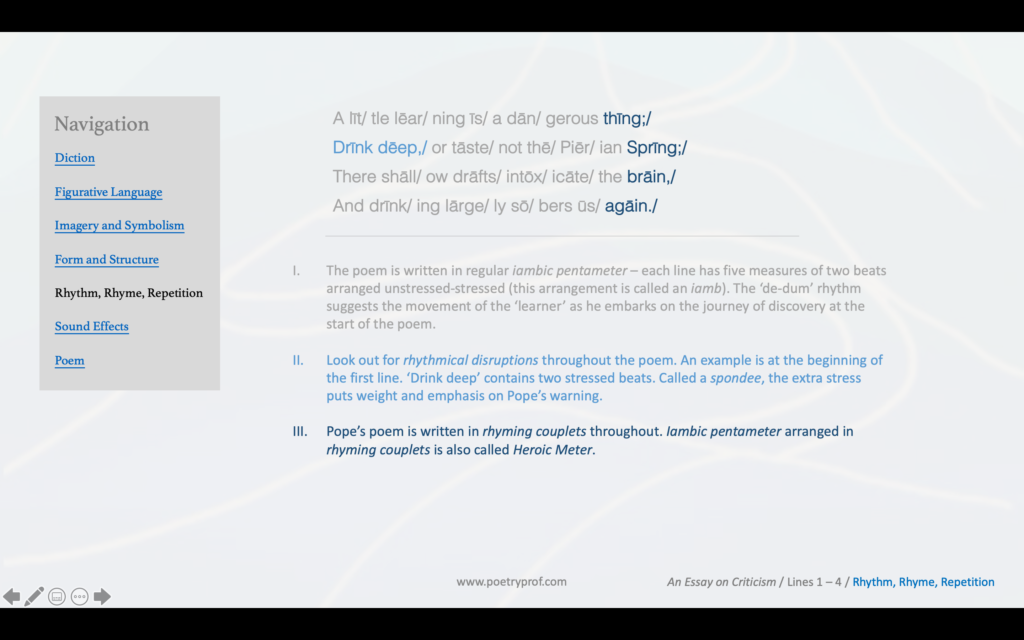

If you’re a student reading this who thinks you might be able to use Pope’s poem as an excuse not to do your homework or give up on your own writing: you shouldn’t be too rash. Pope’s not suggesting we should quit. Instead, he’s warning us that what might seem like a shallow pool is in fact a deep river of knowledge. Once you jump in, the current will sweep you away and there’s no going back. The poem is a criticism of unpreparedness and arrogance rather than an acknowledgement of futility. In fact, an element of form suggests that, for all the faults Pope has pointed out in young people who are too confident in their limited abilities, it is much more praiseworthy to try and fail to conquer the heights than never to try at all. The poem is written in iambic pentameter that is constant and regular as if, no matter how tough the going gets, the young explorer doesn’t give up. Compare these two lines, with iambic accents marked, from the beginning and end of the poem to see how the rhythm is unfailing:

A līt/ tle lēar/ ning īs/ a dān/ gerous thīng;/

The incrēas/ ing prōs/ pect tīres/ our wānd/ ering eȳes,/

More, the poem is arranged in rhyming couplets (the rhyme scheme is AA, BB, CC and so on). Rhyming couplets written in iambic pentameter are traditionally known by a more dramatic name: heroic couplets. Pope was widely considered to be the master of writing poetry in heroic couplets; using them here implies that Pope ultimately believes any young person who’s brave – or foolhardy – enough to embark upon the lifelong journey of learning is worthy of praise.

The structure of Pope’s poetical essay matches the message he’s trying to convey – that, once you start learning, you won’t be able to stop. Look carefully at the punctuation marks, in particular his use of full stops. You’ll find the first one at the end of the fourth line, the second after the tenth and the third at the end of the poem (after eighteen lines). In other words, if the poem was arranged in verses, the first verse would be nice and short at only four lines, the second would stretch to six, but the final verse would have doubled in length to eight lines. Expanding sentences represent the conceit – a little learning is a dangerous thing – and match the images of the landscape expanding (eternal snows, increasing prospect, lengthening way) as you read further down the poem.

The end of the poem brings Pope’s criticism to its conclusion. We see the young explorer break through the eternal snows , climb above the clouds, and stand triumphantly on the mountain top, proudly surveying his achievements. Only now does he take a moment to look more deliberately at the mountains he’s trying to conquer:

The eternal snows appear already past, And the first clouds and mountains seem the last:

Be alert to two words that might seem insignificant: appear and seem, words that signal the mistake the explorer made; he thought that he had already past the bulk of his journey. Read carefully to punctuation as well, and you’ll see the colon – a longer pause, which creates a caseura – representing the traveler pausing at the moment of his triumph… and it’s here that realisation finally dawns. Despite the difficulty of his climb thus far, the landscape (increasing prospect) stretches out endlessly in front of him: Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise. Here, repetition mixes with all that increasing and lengthening diction to create a surreal image of an ever-expanding landscape stretching out ahead. You might also notice P sounds peppering the last two lines of the poem in the words peep, Alps, Alps, and prospect. Coming from a category of alliteration called plosive, this sound is excellent at conveying a release of negative emotion, as it is formed by pushing air through closed lips. The sound helps us perceive the taste of victory turning to defeat as the weary traveler’s shoulders slump at the prospect of the endless climb still to come.

What does Pope offer as a solution? He already warned us at the start of the poem: drinking largely sobers us again. Suddenly, the importance of the word sober becomes clear. While the idea of heading off on this journey of discovery was intoxicating, firing up those with passion to learn, discover and explore – the reality is very different. That young, over-confident learner/explorer is gone, replaced by a wiser, but more world-weary traveler who can finally see the true scale of the task ahead. By now it’s too late, he’s stuck on the mountain top and there’s only one thing he can do – go onwards!

So drink deep and be prepared to encounter much more than you expected when you set out on your journey.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- from Essay on Man by Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism was not the only poetical essay written by Pope. French writer Voltaire so admired Pope’s Essay on Man that he arranged for its translation into French and from there it spread around Europe.

- Marrysong by Dennis Scott

As in Pope’s poem, Scott creates a metaphor of the landscape to represent his marriage. He is an explorer in a strange land – each time the explorer glances up from his map, the landscape has changed and he’s lost again.

- Through the Dark Sod – As Education by Emily Dickinson

Victorians brought many different associations to all kinds of plants and flowers. In this Emily Dickinson poem, the lily represents beauty, purity and rebirth. This link will also take you to a fantastic blog which aims to read and provide comment on all of Emily Dickinson’s poems. So that’s 1 down, and nearly 2000 more to go…

- In the Mountains by Wang Wei

Often spoken of with the same reverence as Li Bai and Du Fu, Wang Wei is a famous imagist poet in China. In these exquisite portrait poems, Wang Wei paints pictures of the impressive landscapes of his mountain home.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying An Essay on Criticism at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs;

- A sample analytical paragraph for essay writing;

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem;

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on analysing diction and explaining lexical fields;

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap;

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision;

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism? Do you agree that the poem somewhat singles out young people? Can you relate to Pope’s messages about the temptations of learning? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

I would like to have an explanation of the frontispiece appended to the 1711 edition of An Essay on Criticism. Is it related to Pierrian Spring and the Muse of Poetry referred to in the poem. I would like to know more on it.