Get your tickets and board Arun Kolatkar’s mysterious old bus for a mystical nighttime journey.

“Audacious is the first word that comes to mind…”

Taran Deol, writing in The Print.

Arun Kolatkar’s The Bus is the first poem from his collection Jejuri, a thirty-one poem takedown of religious hypocrisy in modern India for which he won the Commonwealth Prize for Poetry in 1976. Despite its mundane subject matter – the titular bus is one of a fleet of state transport buses whisking people from one place to another across Maharashtra, one of India’s most populous provinces and Kolatkar’s home city of Mumbai – The Bus is a poem bursting with dramatic imagery, tension, and ambiguity. Supposedly ferrying a group of tourists and pilgrims to Jejuri, site of a sacred Hindu temple, as the bus speeds through the night we start to wonder where it’s really going, and whether one particular passenger will find what he needs when The Bus finally arrives:

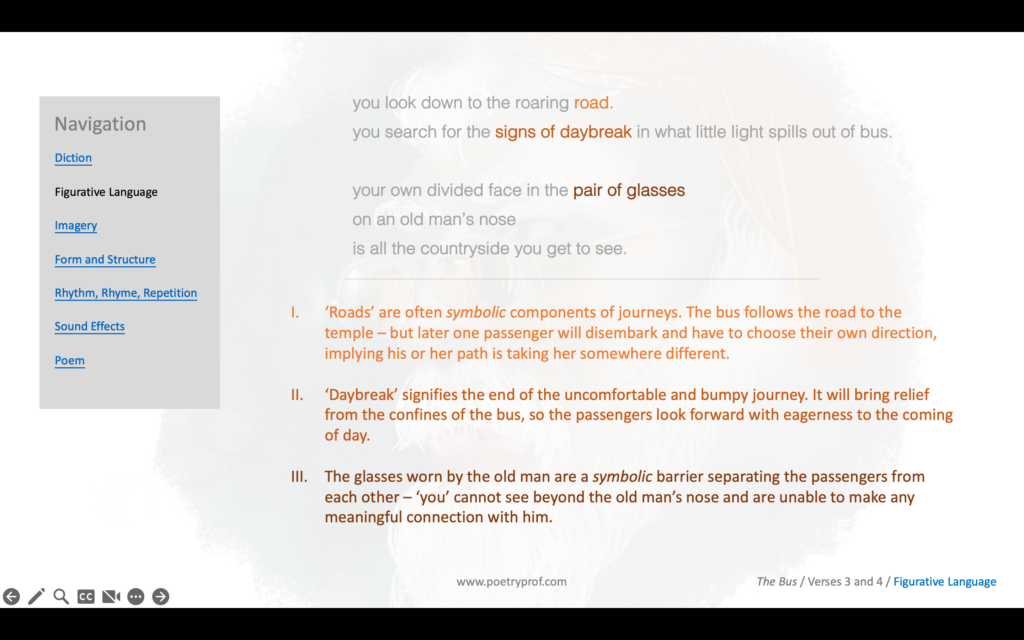

the tarpaulin flaps are buttoned down on the windows of the state transport bus. all the way up to jejuri. a cold wind keeps whipping and slapping a corner of tarpaulin at your elbow. you look down to the roaring road. you search for the signs of daybreak in what little light spills out of bus. your own divided face in the pair of glasses on an old man’s nose is all the countryside you get to see. you seem to move continually forward. toward a destination just beyond the castemark beyond his eyebrows. outside, the sun has risen quietly it aims through an eyelet in the tarpaulin. and shoots at the old man’s glasses. a sawed off sunbeam comes to rest gently against the driver’s right temple. the bus seems to change direction. at the end of bumpy ride with your own face on the either side when you get off the bus. you don’t step inside the old man’s head.

What I love most about this poem is the atmosphere of mystery and mysticism. As the bus speeds through the night, the passengers sit shrouded in darkness, the tatty interior illuminated intermittently in flashes of reflected light. Everything in the poem seems loaded with significance – from the road, to the passengers, to the destination, to the bus itself – but the definitive meaning of these symbols is as hard to grasp as the sunlight that gradually dawns outside. Much relies on the allusion to jejuri at the end of verse one: an allusion is a reference to something outside the text that is never explained. Writing from his favourite seat in a Mumbai café for an Indian readership, this is an example of knowledge that Kolatkar assumes you will have. Jejuri is the site of one of India’s most holy and visited Hindu temples. The passengers (one of whom is cheekily referred to as you, as if the poet and reader are actually sitting on the same bus) are travelling to visit Khandoba, the resident deity of Jejuri temple who is thought to grant wishes. Once you have that tit-bit of knowledge, you can begin to dig into some of the poem’s ambiguities with a little more confidence that you’re not just striking out in the dark. For example, while some of the travellers on the bus are pilgrims on a journey of religious devotion, it doesn’t seem like you are one of them. This is one of the most enticing mysteries of the poem; what, then, are you doing on the bus? If you’re not on a pilgrimage – where are you really going?

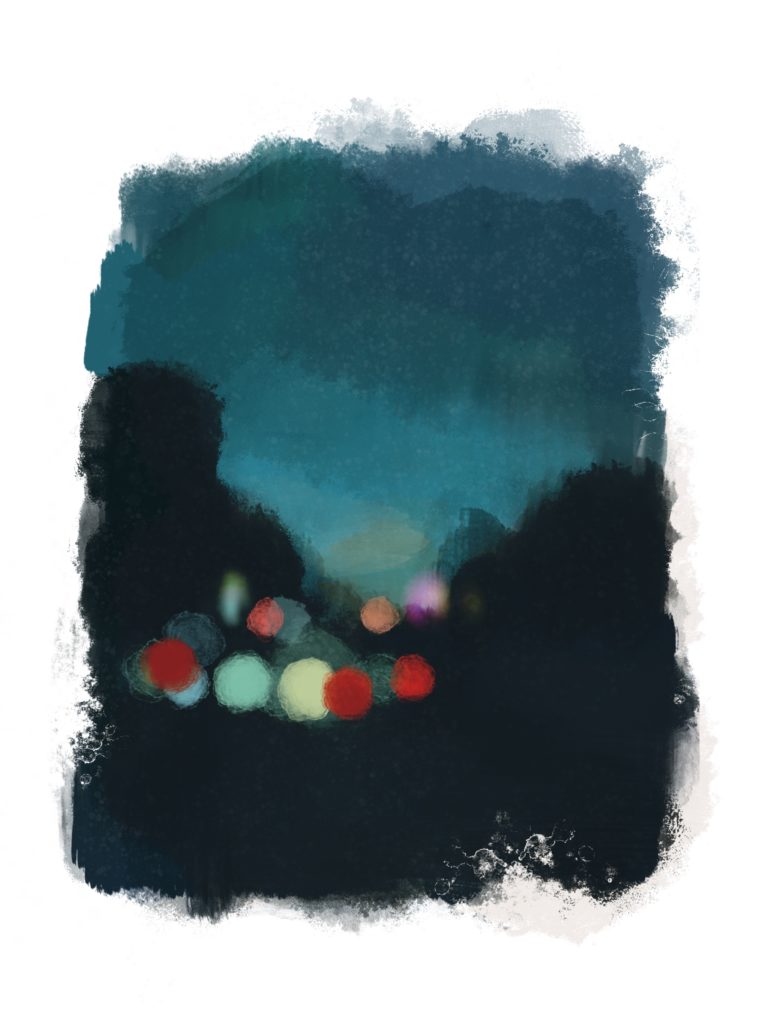

The journey to Jejuri is long and not particularly comfortable. The bus is old; in place of windows, plastic or cloth sheets (tarpaulin flaps) have been buttoned down to keep out the cold wind, which makes the bus seem quite old-fashioned and even anachronistic (out of time). Repeated three times in the poem to accentuate the bus’s age, the tarpaulin flutters in the strong wind, slapping at the passenger’s elbow, perfectly encapsulating the make-do-and-mend experience of long-distance road travel. There’re holes (eyelets) in the tarpaulin flaps so the little light inside spills out carelessly, as if the bus is an imperfect vessel. Because the flaps are buttoned down, the passengers are stuck inside the bus and have no choice but to endure the discomfort of the journey all the way to the end. Diction such as cold wind, whipping and slapping create a physical impression of discomfort, bordering on pain, and an onomatopoeia describes the roaring sound of the journey. As well as bringing to life the growl of highway traffic as the bus hurtles through the night, the word conveys menace and threat; roaring is how big animals warn you that you’ve gotten much too close. The sound is amplified through its alliteration with road. The ride is described as bumpy; either the road is uneven or the bus’s suspension is shot to bits, making the journey something to be endured rather than enjoyed. The passengers look forward to the coming morning (search for signs of daybreak) which is the signal that their arduous journey will soon be over. When the sun finally arrives, it comes quietly and gently, words that contrast with the jerky, bruising ride and convey a sense of relief that the end is finally in sight.

It’s tempting to interpret the bus as a microcosm of wider society. A microcosm is a type of symbol that represents an entire society in miniature; calling it a state transport bus implies it stands for Maharashtra or even India itself. The discomfort of the journey suggests the chaotic day-to-day challenges of life in the world’s largest democracy. National division is hinted at, with an acknowledgement of religious and social division particular to India. One of the passengers on the bus, identified by the castemark he wears on his forehead, is probably a pilgrim on a devout religious journey; another passenger (you) probably isn’t, so not everybody on the bus shares the same goal. The centrality of the poem’s defining image – a passenger sees his own divided face superimposed over the landscape (your own divided face… is all the countryside you get to see) – is a not so-subtle way of implying that India is a nation defined more by division than unity. Indeed, the poem is filled with contrasts and oppositions that are not easy to reconcile; past vs present, old vs young, interior vs exterior, light vs dark, up vs down, day vs night, pilgrim vs traveler. As a relic from the past, carrying old men wearing prominent castemarks to a temple high up in the mountains, maybe it’s not surprising one particular passenger feels a little out of place trapped on the bus.

The bus’s progress is unsteady and uneven; no one can really see outside the bus and they just have to trust they’re getting to where they want to be: the word seem is employed twice (for example, seem to move continually forward ) to imply that, perhaps, the feeling of progress doesn’t quite match up to reality. For all the passengers know, they might be stranded in dark and discomfort for a long time yet to come. Equally, the poem’s form reflects the uncertainty of the journey: written in free verse, some verses are two lines long and others three. There’s no rhyme or reason to the poem’s line lengths, no rhythm or meter to follow. Kolatkar doesn’t capitalise any of his headwords (the first word of each line) so we are denied even the most basic of conventions as we read. We already mentioned how the daylight eventually brings relief – but it also tries to force its way on to the bus like a gun-toting high-jacker: a sunbeam aims through a tiny hole in the tarpaulin, shoots at the old man’s glasses, and resembles the barrel of a sawed-off shotgun placed against the forehead of the unlucky driver. This wonderful personification oozes threat and malevolent tension, as if the sun has been patiently waiting for the bus to fall into his ambush. After this dramatic action, the bus seems to change direction; if it is a microcosm of wider Indian society, what is Kolatkar implying about the forces who set the direction of the nation? Perhaps it will come as no surprise to discover such a cinematic image in a poem by a man who was a graphic designer and worked in film and advertising before turning to writing; Kolatkar controls light and dark expertly in the poem, like a cinematographer crafting potent visual images.

The poem’s boldest feature is the voyeuristic way it positions you on the same bus as the speaker, as if he is watching you and narrating your actions. Your identity is elusive; there’s no omniscient speaker here, so we never get to see inside your head and read your thoughts. Kolatkar writes in the objective second person, describing only actions and impressions. We never get any firm clues as to your appearance, even though we get glimpses of your face reflected in a pair of spectacles. It feels like, for you, this is not a straightforward physical journey from point A to point B, but more of a journey into the unknown. The microcosmic bus creates a temporary community of people all sealed up inside and there are plenty of opportunities for interaction between passengers. But you seem uncomfortable with the other people on the bus, preferring to look outside and down to the road than explore inwardly. The poem is full of diction (Kolatkar’s choice of words and phrases) suggesting you are trying to find something – you look down… you search for… is all you get to see… you seem to move toward a destination… beyond… beyond – but no sense that whatever you’re looking for is ever clearly defined. Being unable to see much in what little light spills out of the bus doesn’t help. At one point, the bus seems to change direction but you remain onboard until the end of the ride, like it doesn’t really matter where you ultimately end up.

The sense of being lost in a wider world – of a long, open road taking you on a journey with no clearly defined end – is evoked by the poem’s sound effects and auditory imagery. Patterns of sound tend to feel formless and directionless, as if the direction of travel is uncertain. Take verse three as a case in point:

you look down to the roaring road. you search for the signs of daybreak in what little light spills out of bus.

These lines are filled with a category of sound called liquid. Made with the letters W, R and L, liquid not only evokes the sensation of the bus’s movement, but also feels a little amorphous, creating shapes and sounds that seem intangible. Roaring road and what little light spills are packed full of liquid sounds that blend and flow amorphously. Kolatkar mixes in liberal amounts of sibilance, a fizzing S sound that mimics the rush of air and wheels as the bus speeds through the night: search for signs… spills out of bus. Complimenting both are frequent assonant combinations: O sounds are particularly effective (you look down to the roaring road), echoing roundly as if the night is vast, road is long and the passengers are lost somewhere in the hinterlands of Maharashtra. You’ll find these combinations at work elsewhere in the poem: cold wind whipping, a sawed-off sunbeam comes to rest, and more. Compare the directionless feel surrounding you with the focused intentionality of the sun that rises, aims and shoots with purposeful accuracy. The contrast between certainty and uncertainty could not be more clear.

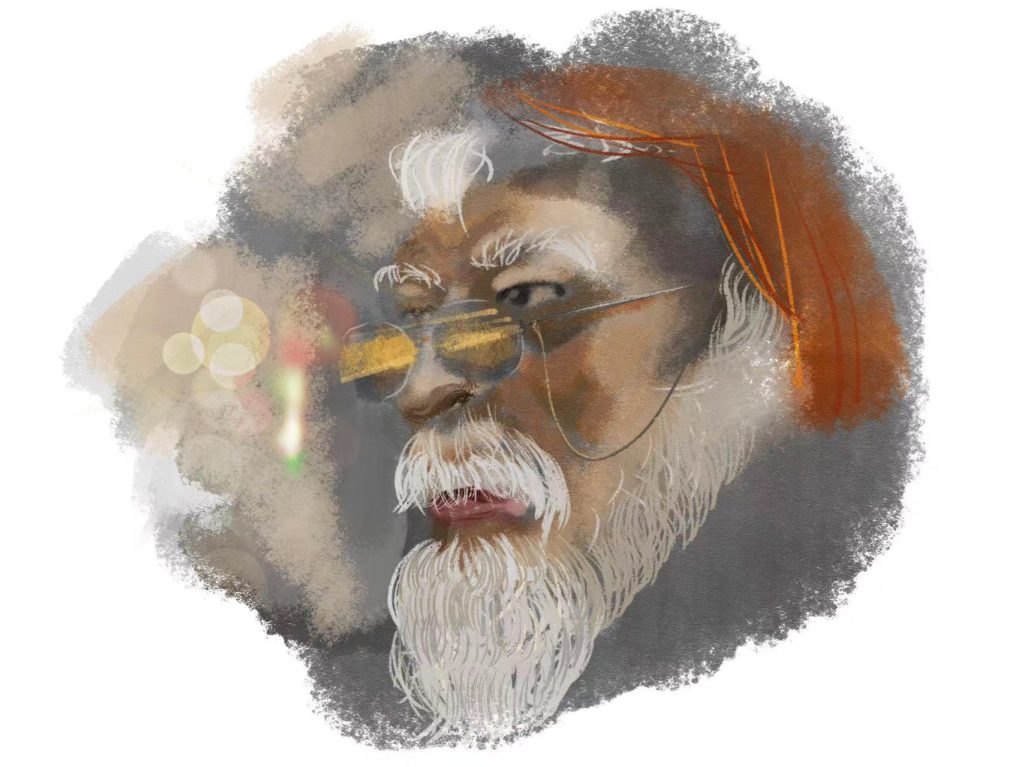

Nowhere is the suspicion the traveller just doesn’t fit in with the metaphorical community of bus passengers more tangible than in his failure to connect with the old man wearing a castemark. From this detail we can infer the old man is a pilgrim, a true believer in Khandoba (the temple deity). A ‘caste’ is a particular social group into which an individual is born in India, similar to a tribe or clan. In the present day, the word ‘caste’ is loaded with political significance, used as shorthand for the inequalities of modern Indian society and related to ideas such as prejudice and injustice. We should be careful, though, about over-analysing the old man’s castemark and loading it with ideas about ‘prejudice’, for example, that the rest of the poem simply doesn’t support. In this case it’s no more than a single spot of colour on an old man’s forehead indicating how he ‘belongs’ to a community in a way the other passenger doesn’t. Technically, his castemark is an example of metonymy, a sub-category of metaphor by which the whole of an individual is represented by a single part or one defining feature. For example, we might refer to a king or queen as ‘the crown’ or a reliable friend as ‘a safe pair of hands’. In this case, the old man is represented by his castemark; comfortable in himself, his faith, and where he is heading, the old man proudly wears the mark of his religious purpose. Compare this with the murky identity of the traveller, hidden behind the vague pronoun you, shrouded in darkness, unsure of where he is going and why, glimpsed only in fractured, divided images. He’s an aimless traveller rather than a dedicated pilgrim. In verse five, Kolatkar briefly suggests the possibility that the two of them might form a connection. He uses internal rhyme to create a link between the words forward/towards and diction (destination, forward, toward) implies they might actually be getting somewhere. But perhaps the castemark, symbol of the differences between them, is too much of a barrier and the traveller’s stare goes beyond… beyond… until the moment is lost.

Let’s take a closer look at the pair of glasses perched on the end of his nose . The glasses function as another symbolic barrier between the old man and the traveler, who is unable to see beyond the split reflection of himself in the dark lenses. Unsure of his direction and uncertain of his place, the traveller instead sees his own divided face, a fractured image that perfectly represents all the doubts and questions he has about himself and where he belongs. The image lingers and is repeated later in the poem: your own face on the either side when you get off the bus. The phrasing of this line is a little uncomfortable, as if he’s been split in two, half of him staying on the bus and the other half getting off. Repeating the same divided image at the end of the poem is a fantastic way of implying he has yet to reconcile any of his doubts. Throughout the poem, Kolatkar has employed full stops to fracture the experience of the journey into pieces and sometimes they also seem to create physical marks of separation on the page, not least in the line you seem to move continually forward. toward a destination. In this case, the poet’s punctuation mimics the disconnection between you and the old man.

Therefore, when the bus reaches the end of its bumpy ride it feels like the central character’s journey isn’t over. The temple is nowhere in sight, probably because it was never the real reason to get onboard in the first place. The poem refuses to grant any sense of conclusion (which makes sense when you know it was the first in a thirty-one poem cycle). The traveller remains unsure of his next steps; his final action is, in fact, an inaction: you don’t step inside the old man’s head. This last ambiguous metaphor suggests he doesn’t follow the old man to the temple and rejects any sense of community or guidance he’s implicitly offered. Instead, he’s going to strike out on his own. This is not necessarily a bad thing. After all, the old man, like the anachronistic bus, belongs to a past-India, a country whose problems and solutions might be very different to the India of today. Perhaps it’s better not to follow in the footsteps of the older, more traditional generation who seek answers from temple deities. This ‘community’ of castes and religions is not necessarily the one the traveller needs to join. By choosing to go it alone, even if he’s unsure of the direction he should take, Kolatkar implies his journey into the future is untrodden, the road from here unpaved.

A relic from the past, the bus can only take you so far. You must decide where to go next for yourself.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Turnaround by Arun Kolatkar

Another poem about traveling across Maharashtra. Setting out from Mombai, Kolatkar writes about places he passes through, people he meets, what he sees. The sights, sounds, and foods of India are brought to life – before he turns around and heads back again.

- Travelling Again by Du Fu

Written by one of China’s most famous poets in 751 on his journey to the Temple for Cultivating Enlightenment in Chengdu.

- Song of the Open Road by Walt Whitman

If ever anybody thought the journey is more important than the destination, it was Walt Whitman. Here he imagines what seems like the entire world travelling down an endless road, finding meaning in exploration. He ends by asking, ‘will you come travel with me?’

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Bus at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the bus as a microcosm of society.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Arun Kolatkar’s poem? Do you think the bus is meant to represent wider society? Where do you think the central passenger is going to go next? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Absolutely. It does not sound pretentiously ‘erudite’. And is written in ‘correct’, standard English, without any flaw. Students The critical terms used and their examples from the poem, are correctly identified.

Hi Poonam,

I was reading somewhere about Kolatkar’s decision to write in English, which was a very conscious decision, although I think he hesitated over making it. I can’t remember the exact interview I was reading this in though. I hope I can find it again.

The analysis is so apt and thought provoking. Additionally helpful for my masters exam.

Thanks and great work!

hello what is the relation of the poem to the partion of India to the poem