Follow Musaemura Zimunya back up an endless river into Zimbabwe’s forgotten past

“…culturally immersive and nationally minded writing… [has] a foundational place in the Zimbabwean canon”

Onai Stanely Mushava writing for This Is Africa, an educational and cultural online publication

Musaemura Bonas Zimunya has seen change in his life. Born in 1949 when South Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) was administered by Britain as a colonial state, he saw his country ostracised by the international community in 1965 when they attempted to break away from the British Empire. Finally, Zimbabwe achieved formal independence in 1980, but their troubles didn’t end there. At the turn of the millennium the economy all but collapsed and Robert Mugabe, once a voice of freedom and independence, became one of the twenty-first century’s most notorious dictators. You can read about Zimbabwe’s complex history here (scroll down until you find the British South Africa Company’s arrival in the 1880s and begin there). Zimunya has been writing poetry since he was at school (his early education was in Rhodesia; he later went to university in England). His poems are powerful, angry, sometimes grand in scale, often concerned with history and politics. His depiction of history is neither simple nor straightforward. For example, after Zimbabwe was finally recognised as an independent nation in 1980, Zimunya wrote these words of warning:

We, indeed, are arrivants with blister feet and broken bones

that will learn the end of one journey

begins another.

Today’s poem, published in his collection Country Dawns and City Lights, begins well over a century ago, when the British first took control of the country. Speaking from a present-day perspective (the poem was written in 1985) the poem looks back over the arduous and difficult road to independence, describing the bitter colonisation era that forced the country into the modern age by building over authentic cultures and traditions. But Zimunya doesn’t believe that history can be cast aside so inconsequentially; his poem retraces his ancestor’s long journey back into the colonial past… and beyond, to a forgotten time that exists on the periphery of history:

Through decades that ran like rivers

endless rivers of endless woes

through pick and shovel sjambok and jail

O such a long long journey

When the motor-car came

the sledge and the ox-cart began to die

but for a while the bicycle made in Britain

was the dream of every village boy

With the arrival of the bus

the city was brought into the village

and we began to yearn for the place behind the horizons

Such a long travail it was

a long journey from bush to concrete

And now I am haunted by the cave dwelling

hidden behind eighteen ninety

threatening my newfound luxury

in this the capital city of my mother country

I fight in nightmarish vain

but my road runs and turns into dusty gravel

into over beaten foot tracks that lead

to a plastic hut and soon to a mud grass dwelling

threatened by wind and rain and cold

We have fled from witches and wizards

on a long long road to the city

but behind the halo of tower lights

I hear the cry from human blood

and wicked bones rattling around me

We moved into the lights

but from the dark periphery behind

an almighty hand reaches for our shirts.

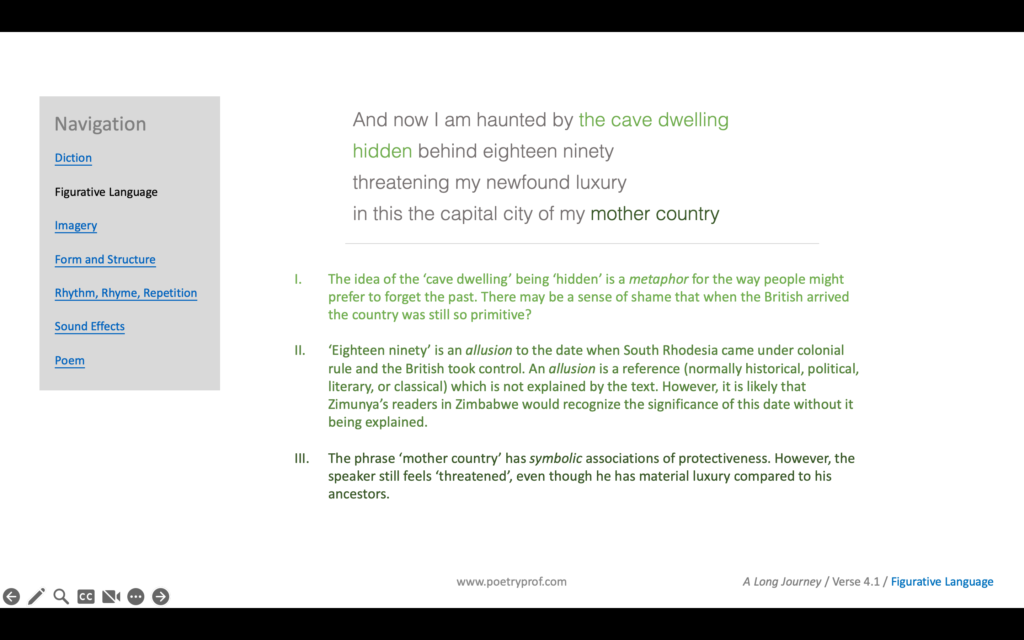

In the first half of A Long Journey, Zimunya begins the story of Zimbabwe’s modernisation in eighteen ninety when the British came to Rhodesia, as it was then called. This fateful year is presented to us as an allusion in verse five; an allusion is a reference to a person, event, piece of writing, or something else that is not explained in the text. Unless the publisher provides a note, or unless your general knowledge is up to scratch, it can be easy to miss the importance of an allusion, or even to recognise it’s there in the first place. However, the number eighteen ninety is of such significance that I assume Zimbabwean readers will recognise its import. Zimunya describes the country’s history before this year as a cave dwelling hidden behind eighteen ninety, as if the British arrival pushed natural history to one side. The result is a kind of collective amnesia surrounding Zimbabwe’s past. He uses visual imagery of light and dark as a code for the remembering and forgetting of history. As the country moved into the light of modernity, its people were symbolically separated from historical and authentic cultures and traditions, leaving themselves metaphorically in the dark when it comes to any sense of their ‘true’ selves.

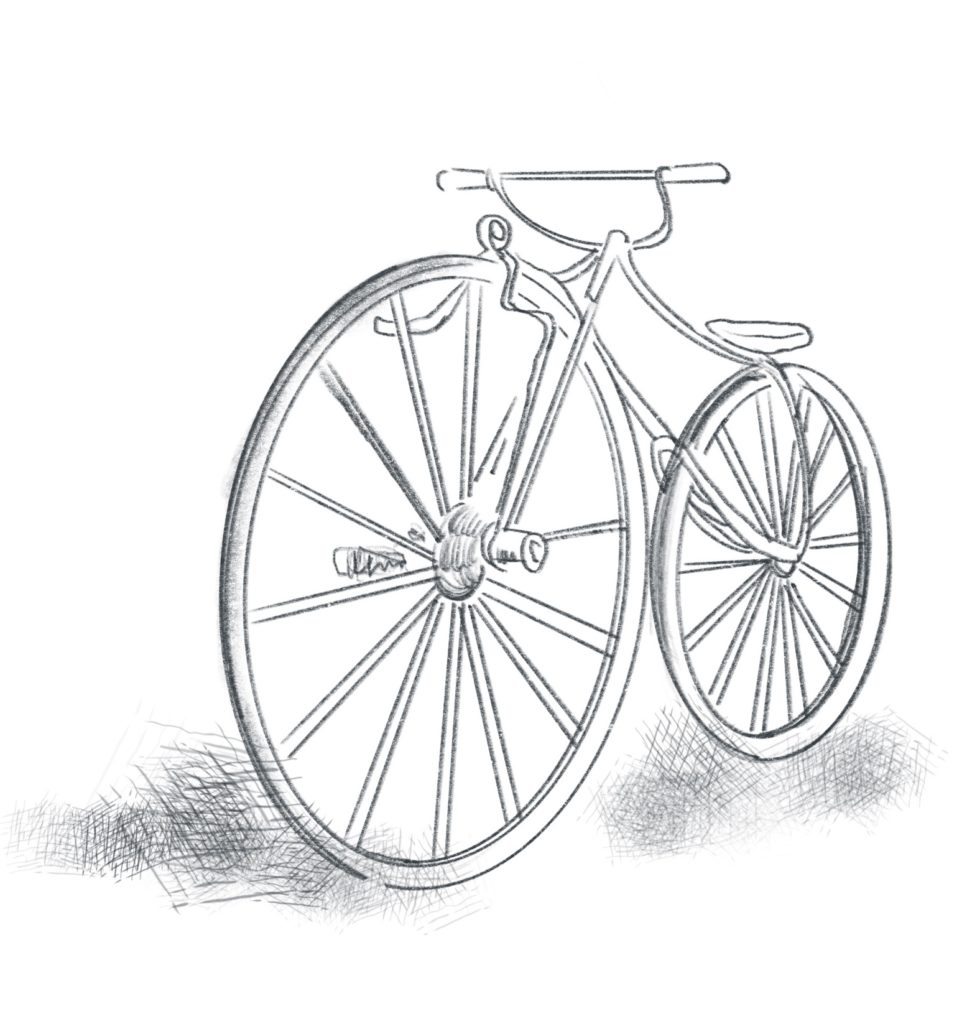

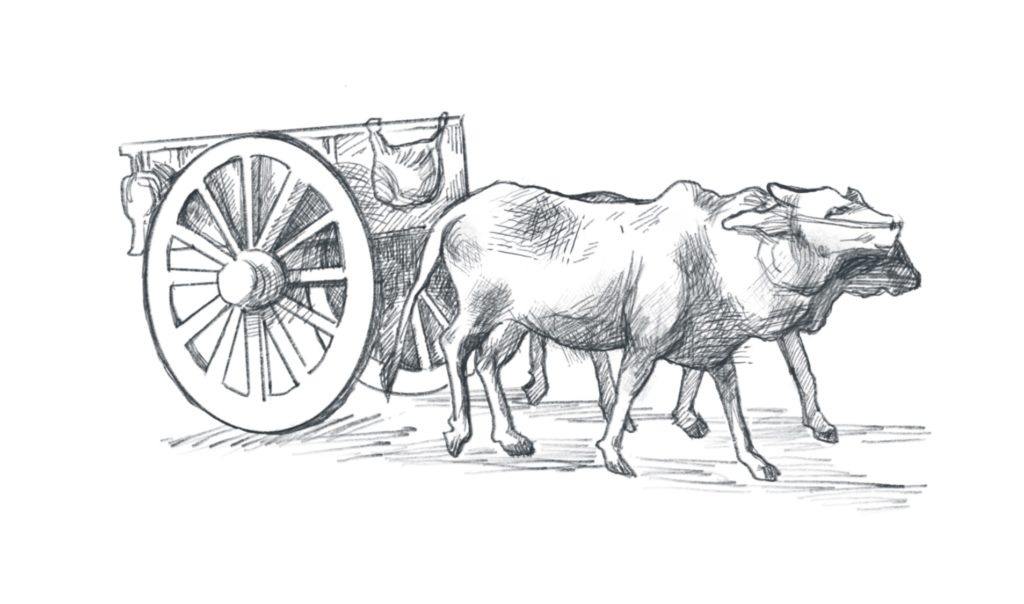

Therefore, the poem is an attempt to both retell the story of Zimbabwe’s colonial history from eighteen ninety to the present day, and also to delve back to an even earlier, forgotten time. The central feature of this story is the extended metaphor of A Long Journey. An extended metaphor is one that continues for more than a single line in a poem, perhaps running from verse to verse, or even stretching through the whole text. Here, the metaphor begins with the title and is the thread that stitches all the verses together. At various points the journey is reimagined in different ways: first it’s like a river, is later called a travail, and is also expressed as a road along which the people of Zimbabwe have travelled. While there’s a danger of the metaphors becoming a bit mixed, I think they compliment one another nicely. Where the river flows like a river of time, the road winds from place to place, giving the history of Zimbabwe physical and temporal dimensions; in telling the story of an entire country, the poem moves through both time and space. (Occasionally, it can be hard to separate these two strands: for example, the road from bush to concrete can be visualised in terms of a physical migration of people from rural to urban settings in space, or as the replacing of villages by urban development over time.) The poem is replete with symbols that represent the country at various stages on its colonial journey. In the second and third verses, these symbols take the form of modes of transport: sledge, ox-cart, bicycle, motor car, bus, arranged in chronological sequence from oldest to newest. This choice associates perfectly with the extended metaphor of a journey along a road of time. The sledge and ox cart carried people and farm produce to market long ago; after the British arrived these were replaced by the bicycle and motor car. Finally, the bus connects vast regions of the country together, allowing for the large-scale movement of people and construction materials, and accelerating the development of a modern, urban culture as the city is brought into the village.

Whether by river or road, the journey is a story of hardships endured along the way and Zimunya doesn’t flinch from expressing the pains and difficulties of the country under colonial rule. The river is described as an endless river of endless woes, where simple repetition makes it seem like this arduous period of time would never end, so that decades take an eternity to pass. In fact the river is so colossal, it has washed away any sense of time before eighteen ninety: the endless river is all that was and is, according to a colonial history of the country. The word woe explicitly means ‘misery’ or ‘great sadness’ and travail connotes a painful and laborious effort. The sjambok is a heavy leather whip, traditionally made from rhinoceros or hippopotamus hide, no doubt used to incentivise field workers or keep control in overcrowded jails. These are just a few examples of the lexical field of hardship employed through almost the whole poem, sometimes, as in pick and shovel, used literally, at other times used figuratively. Such figurative moments include a grassy foot track described as beaten and the weather being threatening. The relentless brutality of Zimunya’s diction ensures that the story of colonial subjugation is front and center; unlike the more distant past, it cannot be romanticised or wished away. It’s the poetic equivalent of forcing someone to look at something disturbing they would prefer to avoid.

Zimunya’s attitude towards the colonial period is far from simplistic. While he doesn’t shy away from presenting its brutality, he also implies the progress made by the country during this time. I’m reminded of a famous scene from the film Life of Brian when a group of revolutionaries ask, ‘what has the Roman Empire ever done for us?’ The symbolic bicycle made in Britain is a case in point and worth spending a few moments examining more closely. On one hand the coming of the bicycle pushes out traditional symbols of national character (the sledge and ox-cart), replacing them with something made in Britain, stamped indelibly with the reminder of Zimbabwe’s backwardness. The metaphor began to die uses melancholy diction that laments the passing of a more authentic way of life when people were closer to nature. Equally, you might detect a certain regret in the syntax of the city was brought into the village – like it or not, rural cultures were forcibly destroyed by urbanisation. On the other hand, this imported technology enlarged the country, allowed people to travel outside their villages, and opened their eyes to new ideas. The bicycle is described as the dream of every village boy and prompts them to yearn for the place behind the horizon, lovely lines that acknowledge how people are stimulated by social and historical changes. Actually, dream and yearn are probably the most optimistic words in the entire poem and a departure from otherwise painful lexical choices! As paved roads, bikes, and motorised transport made the country more accessible, minds opened up and the ceiling of people’s ambition was raised. These lines are adorned with some auditory embellishments: half-rhymes (came/Britain, die/boy, yearn/horizon) and energetic alliteration (but, bicycle, Britain, boy) using the letter B encourages us to feel that, despite terrible hardships, over time things materially improved for Zimbabwe’s people.

No poem about the movements of history would be effective without features that suggest the inevitable passing of time. Moving from the past to the present, Zimunya has his poem flow irresistibly down the page, never pausing between images, barely skipping a beat from line to line, and verse to verse. Continuous enjambment (the flowing of one line into the next with no pause or punctuation) helps the reading experience resemble the flow of that endless river; for instance, in verse two when the motor car came the sledge and the ox-cart began to die one line runs smoothly into the next. Faint sound devices such as alliteration and consonance accentuate the poem’s sensation of flowing through time, none more so than sibilance in words such as: endless rivers, endless woes, shovel, sjambok, such, bicycle, bus, and others. One defining feature of the poem I’m sure you’ve noticed is the lack of end-stopping (punctuation that is normally seen at the end of lines of poetry) until the full stop at the end of the last line. Similarly, apart from the first word in each verse, headwords (the first words of each line which are typically capitalised in poetry) remain uncapitalised here. The poem is written in free verse so there is no regular rhythm or pattern of rhyme. Various verses are all composed to different lengths, making the journey appear haphazard and unstructured. Sometimes Zimunya arranges things in lists (pick and shovel; wind and rain and cold) using polysyndeton (connecting items in a list with the word ‘and’) to resemble the way time jumps, slides and slips forward. Sometimes he juxtaposes words side by side: shovel sjambok is a good example of this, as is the city was brought into the village, juxtaposition transforming a rural world into an urban one in a single line. More examples of repetition (rivers endless rivers of endless woes; long long journey… such a long travail it was a long journey) propel the poem down the page. Such relentless forward motion additionally suggests how the country was forced into the future by colonising powers, regardless of the damage done to traditional cultures along the way.

This idea is given voice in the fifth verse, which brings the poem into the present day: And now. Zimunya carefully controls the poem’s tense; there’s a clear difference between the past tense forms of words used in verses one to four (ran, came, began) and the present tense forms from here onwards: am haunted, threatening, I fight and so on. We learn that now, in the modern day after the hardships of colonialism have passed, the poem’s speaker lives in comparative luxury. He feels privileged, symbolically wrapped in the protective arms of his mother country and ensconced proudly here in the capital city. Or at least he should feel like this. Unexpectedly, he’s struggling with the direction of his thoughts. The end of the fourth verse implied the end of his mind’s journey, but whatever internal road his thoughts travel on, they keep trying to turn back on themselves. A sense of discomfort lingers, concerning both Zimbabwe’s forgotten histories and the inequalities of the present. The image of a halo of tower lights implies a certain area of wealth and luxury – but outside this ‘ring’ parts of the country are still shrouded in darkness, suggesting the benefits of development are not equally shared. And even those within the halo can feel the press of the dark, forgotten aspects of history and culture hidden behind eighteen ninety. On a subconscious level, the speaker feels threatened by these untold stories. Dread infuses the poem’s diction: haunted, threatening, fight, nightmarish, beaten, threatened, blood, wicked, and dark are words drawn from a nightmarish lexical field and the tone of the poem remains bleak. He says I fight in nightmarish vain, suggesting he’s trying as hard as he can to stifle these feelings under layers of concrete, but they insist on pushing back to the surface, like buried corpses striving to exhume themselves. His own use of language betrays the way the past still tugs at him: he uses the old-fashioned word dwelling twice, instead of the more modern ‘house’ or ‘home’.

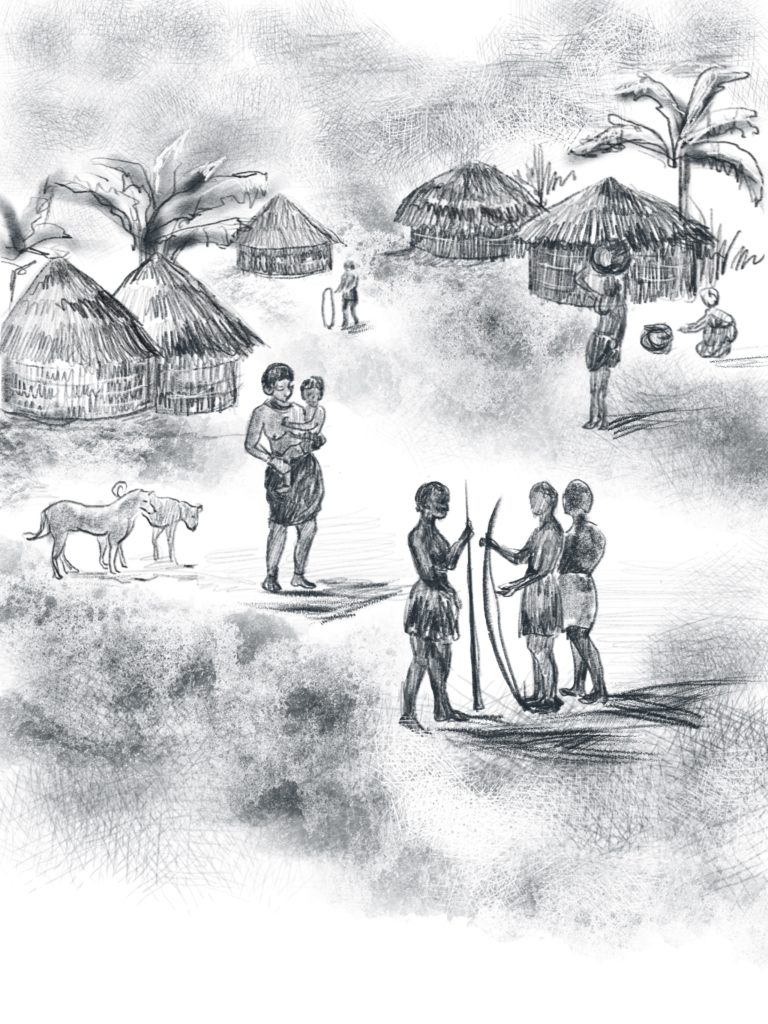

It seems that modernisation has relieved physical hardship but not spiritual hardship; the country may have won independence, but the wounds of colonialism don’t heal easily. Echoes of ancient history reverberate across time. Haunted by the ghosts of history that no amount of luxury can dispel, the speaker’s mind doubles back, retracing the long journey of his recent ancestors. In a mirror-image of the poem’s first half, Zimunya uses symbolism to depict a reverse-urbanisation as the country reverts back to a rural state: concrete towers shrink into plastic huts which transform into mud grass dwellings. The tarmac road degrades into a beaten foot track and the whole country devolves to the cave dwellings of prehistory, before the British ships even arrived. This is the high-point of the poem for me; the visual imagery is cinematically dazzling, as the all the bright lights are swallowed by an encroaching dark and the country’s history is replayed in backwards-timelapse. By the end of the fifth verse, the modern world has melted away, and we’ve returned to a primitive time when exposure to wind and rain and cold could be fatal.

It’s from this forgotten past that the poem’s final images emerge. The last two verses are filled with primeval terrors: witches and wizards, blood sacrifices, and pagan magic. Deriving from a time predating colonial history, these ancient aspects of culture have been forgotten by – and have therefore become dangerous to – their own people. Like a filmmaker playing on fears of the dark, Zimunya ramps up the auditory imagery at the end of the poem: I hear the cry from human blood and the rattling of bones. Onomatopoeia (rattling); aspirant alliteration (hear/human), W alliteration (witches/wizards), plosive B alliteration (blood/bones) like the beating of a drum; the sheer variety of consonant sounds creates an effect called cacophony which can be quite overwhelming. There’s a ritual, even sacrificial, aspect to the last verses, as if we’re surrounded by the ghosts of wizened shamans clad in the vestments of a primitive time, bedecked with bone fetishes and shaking their totems as they cast dire spells. Finally, there’s an almighty hand that reaches for our shirts. Angry at being consigned to the periphery, buried deep in the national subconscious, the hand symbolizes forgotten aspects of Zimbabwean culture forcing their way back to where they belong.

I sense an accusatory element to Zimunya’s writing directed at himself and his countrymen. He shifts his perspective from the personal ‘I’ to the public voice ‘we’: We fled from witches and wizards… we moved into the light… Anaphora drives home his words with force. So keen were Zimbabweans to get to the end of their long journey, they forgot to bring important things with them: ancient history, belief systems, indigenous knowledge, superstitions and stories – things colonialism tried to erase and that material luxury can’t replace. As we reach the end of the poem, we feel how illusory those twinkling tower lights actually are: having been deprived of their authentic past by colonial invaders, and subsequently embracing the material benefits of colonial development, Zimbabweans find themselves unaccountably afraid of the dark.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Hooray for Freedom! by Musaemura Zimunya

As today’s poem suggests, winning independence is not necessarily the end of Zimbabwe’s long and hard journey. In this thickly ironic poem, Musaemura considers ways independence has been corrupted by venal politicians and naivety.

- The Passage by Christopher Okigbo

A poem from Nigeria that takes the form of a prayer to a local deity, celebrating and promoting traditional African beliefs in the face of colonial erasure.

- An African Elegy by Ben Okri

Ben Okri is a famous Nigerian-born poet and this poem describes the mixed blessings of a continent filled with hardship and suffering – but also beauty and transcendence. In asnwer to the question, ‘Do you see the mystery of our pain?’ comes the reply: ‘That we bear poverty and are able to sing and dream sweet things.’

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying A Long Journey at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining symbolism in the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Musaemura Zimunya’s poem? Do you agree that his treatment of colonialism is ambiguous? What do you think the ‘almighty hand’ represents? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Thank so much for your analyses – they are really, really, really good. Insightful and perceptive, well written and presented. Love the line drawings too. A lot of work and thought gone into them. One thing about this one: I don’t quite understand why you suggest using the letter B might make us feel things are materially improving for the people? Thanks, Jeremy

Hi Jeremy,

Thank you so much for your comment and kind words. Such feedback is very motivational, thank you. I find the B alliteration in those particular lines is ‘bouncy’ and ‘lively’, contributing to a certain sense of ‘forward motion’ that can be associated with the idea of material progress. You’re quite right that the idea itself comes from the words and images, not the alliteration.