Nancy Cato races time itself – and almost wins – in this exhilarating ballad from Australia

“…committed not only to her vision of the Australian landscape and history but also to the craft and profession of writing”

from Doctor of Letters honoris causa, University of Queensland, 1990

Life and time are subjects that Cato returns to over and again in her poetry. In 1950 she wrote Metamorphosis, a poem imagining a fantastical transformation into a tree, rooted down in one place strongly and permanently. From this vantage point she is perfectly motionless except for her perception of the slow passage of time:

But rooted content in the one place forever;

no change but the slow march of the turning years,

And the mighty pageant of the night-wheeling stars.

In these lines, a distinction between time and space is made: the speaker fixes herself in place, impervious to all change except for the ‘slow march’ of time that continues regardless. You can feel this theme pulsing through the action of The Road, written a few years later in 1957, expressed not through rooting oneself in place, but in furious motion instead. The Road’s speaker drives so fast that she seems able to suspend time itself! But the effect is momentary: it’s not possible to control time, and almost immediately the spell is broken. Nevertheless, the desire to escape the earthly binds of time, to live in a moment so perfectly that it seems to last forever, to be ‘rooted content in the one place forever’, is the driving concern of today’s poem:

I made the rising moon go back

behind the shouldering hill

I raced along the eastern track

till time itself stood still.

The stars swarmed on behind the trees,

but I sped fast as they

I could have made the sun arise

and night turn back to day.

And like a long black carpet

behind the wheels, the night

unrolled across the countryside,

but all ahead was bright.

The fence-posts whizzed along wires

like days that fly too fast

and telephone-poles loomed up like years,

and slipped into the past

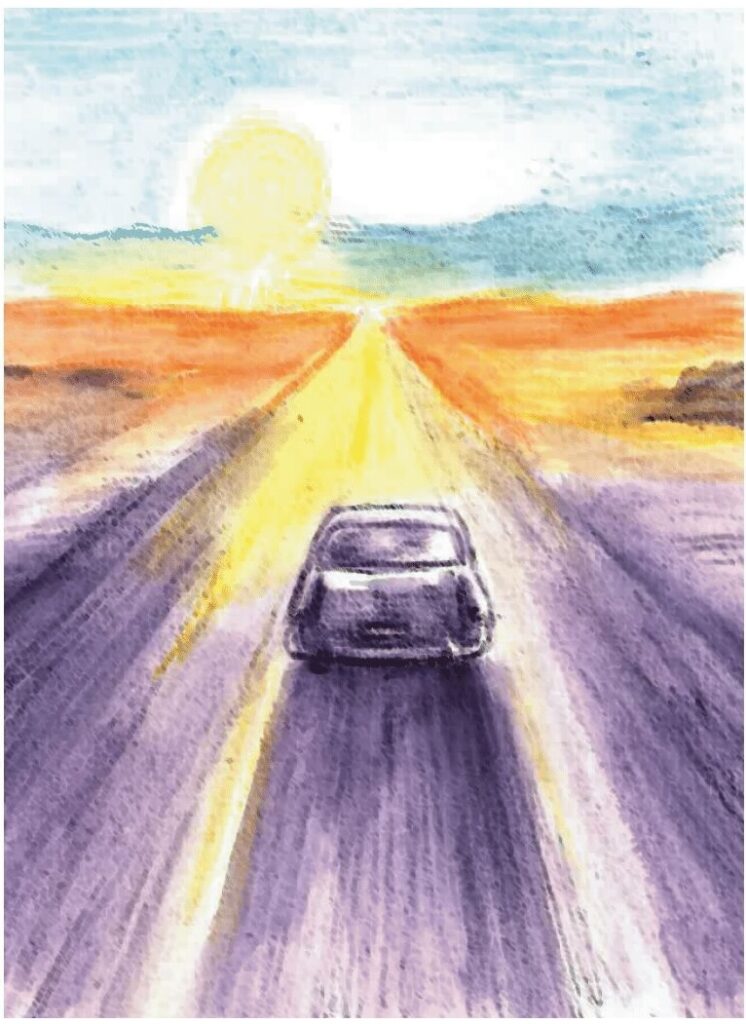

And light and movement, sky and road

And life and time were one,

While through the night I rushed and sped,

I drove towards the sun.

Where Metamorphosis finds contentment in stillness, the speaker of The Road uses motion as her way of seeking control over the passage of time. Reading this poem is akin to the experience of speeding along an empty road through a fantastic outback landscape, window open, sun full overhead, pushing ever harder to keep the car at full throttle. There’s a euphoric sense of giddiness that comes with reading such a fast-paced poem, evoked primarily through Cato’s energetic diction, especially verbs: raced, swarmed, sped, unrolled, whizzed, slipped, rushed, sped and drove all propel the poem relentlessly forwards. Each verse is one sentence long, and Cato uses punctuation sparingly, so one line slips effortlessly into the next without pause or interruption. Conjunctions such as and and but allow her sentences to unroll smoothly, and it seems only a few brief, exhilarating seconds before your eyes reach the last, euphoric, image. At this moment, the word and repeats itself so furiously (six times in one verse!) that the poem seems to accelerate beyond what is physically possible as the speeding car vanishes into the blinding white light of the sun on the horizon.

While we often associate the crafting of imagery with the visual sense, Cato’s poem is charged as much with kinetic (movement) energy. Nowhere is this more elegantly drawn than in the poem’s opening image of the moon disappearing behind shouldering hills that press in on either side of the road, or that she sees receding in her rear-view mirror. On the face of it, this line presents a brilliant visual image of the optical illusion caused by the driver’s speed: she’s moving so rapidly that the moon appears to be going back down behind the nearby hills, forming a shoulder-shaped silhouette against the moon’s bright surface. However, the word shouldering also personifies the landscape with its own eager restlessness, as if the hills are pushing forwards or trying to muscle in on her space. Other features of the environment seem equally capable and desirous of movement: the stars swarmed overhead, fence-posts whizzed, wires pulled tight almost hum with tension, and telephone poles loomed; even the night itself unrolled behind the car’s endlessly spinning wheels. Basically everything in the poem seems animated with the same furious kinetic energy that motivates the human speaker. Kinetic imagery is much embellished with sound patterns, in particular alliteration, that give the lines an urgent, pressing feel, as sounds leap from word to word: made the moon… back behind… till time itself stood still… stars swarmed… whizzed along wires… fly too fast… are all examples of alliterative phrases where repeated letters jostle and push ahead of themselves. Onomatopoeia brings us even closer to a lived experience of speed in words such as whizzed and rushed. As the poem approaches its end, and the car accelerates, these sounds coalesce into a glorious euphony: the lines light and movement, sky and road and life and time were one weave a lattice of nasal Ms and Ns and liquid Ls and Rs which blend together as the road meets the sky and the speaker plunges headlong into the sun’s bright white light.

Behind the poem’s breathless energy, however, lurks an existential fear of time and mortality. You can feel this emotion expressed in words and phrases like fly too fast and looming that suggest a sense of approaching danger, the certainty that, no matter how fast she drives, time will inevitably catch up with her. The road itself is the poem’s most important symbol, a physical representation of the speaker’s lifetime, spooling out between the blazing sun and the encroaching darkness. The contrast between night and day symbolically equates to life and death. The sun, antithesis to night as life is to death, blazes out the promise of life yet to be lived, twists and turns in the road yet to be discovered. But death is an ever-present corollary to life and, in this poem, it follows behind so closely that it seems to emanate from directly behind the wheels of the car. Described as a long black carpet, night covers the living landscape like a funeral shroud. The poem’s most lingering image is that of the car seemingly poised at the intersection of night and day, light and dark. If the speaker slows, night will overtake her; as long as she stays ahead of the fast-encroaching darkness, death can’t catch her – so she speeds along the road as fast as her car will take her. Her desire to exert some kind of control over her life is asserted from the very start; the poem begins with the phrase I made the rising moon go back. Through subsequent anaphora (the repetition of words at the beginning of lines of poetry), Cato conveys the speaker’s desperate need: I made… I raced… I sped… I rushed… I drove… all repeat the same basic I + verb pattern that implies the speaker’s in charge of her life, her car, her speed, and even elements of the world around her.

Therefore, impossible and surreal images of reversing the direction of the moon and causing the sun to rise represents an existential desire to thwart the laws of time. Momentarily, she almost seems to succeed, accelerating to metaphysical speeds that are faster than the clock can measure. At this moment (the end of stanza one) time itself stood still, a sensation that extends briefly into the first lines of stanza two: on describing the movement of stars through the sky she exults: I sped fast as they. If ever you’ve been in that strange situation where the speed of a vehicle you’re in perfectly matches the speed of another vehicle, thus creating an illusion of motionlessness, you’ll recognise the image of keeping pace with the stars presented in this stanza. (This happened to me frequently on a train I used to take: different tracks merged closely together, and sometimes two trains would coast along side by side. When the ride was smooth, the impression that both were stationary was compelling even as we travelled at over 100mph). Almost immediately, though, the speaker’s impossible victory over time is slightly undercut: I could have made the sun arise. Cato inserts this small modal phrase to acknowledge how this is all a feat of imagination only. We can’t make night turn back to day, in the same way we can’t return the dead to life or reverse the arrow of time so it points in the opposite direction. The illusion of time stood still, or of fence-posts and telephone poles slipping into the past, the world around her in motion, is simply a trick of perspective. From the moment we’re born, we’re heading one way only: forward in time.

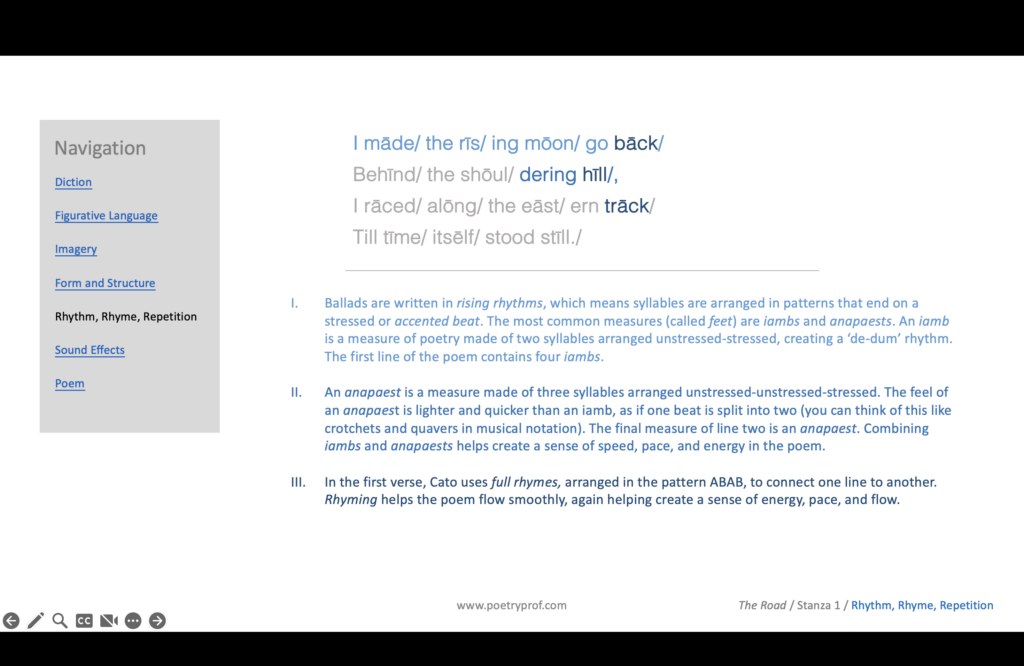

This doesn’t stop us from trying, however, so as her speaker exerts her will over the passing of time, so too does Cato exert control over her poem through conspicuous elements of poetic form. The Road is written as a ballad, a lively and energetic form of poetry that originally set lyrics to music. While nowadays we speak poetry rather than sing, the musicality of ballad poetry survives in both rhythm and rhyme. A ballad is composed of repeated measures (technically called feet) of either two or three syllables each, arranged in rising patterns (measures that end on an accented/strong beat are called rising measures; two syllables arranged weak-strong form a measure called an iamb; three syllables arranged weak-weak-strong form an anapaest). Ballad poems feature a mixture of iambs and anapaests, both rising rhythms that propel the poem forwards. Yet the careful arrangement of regular accented beats also implies the steady controlling hand of the poem’s creator. Ballads are always written in quatrains (verses of four lines) and alternate lines of four beats with lines of three. If you’re not familiar with scansion (the process of marking out a poem’s meter), you can see this at work in the first verse, reproduced here with each foot marked with / and strong beats accented:

I māde/ the rīs/ ing mōon/ go bāck/

Behīnd/ the shōul/ dering hīll/,

I rāced/ alōng/ the eāst/ ern trāck/

Till tīme/ itsēlf/ stood stīll./

You can think of the poem’s form in light of the poem’s theme; as the speaker attempts to exert control over time, so too does Cato carefully control the pace of her poem through the ballad form. Equally, as the natural passage of time reasserts itself, Cato uses a subtle rhythmic disruption to throw us a little off balance, and suggest that, despite her frantic speed, there’s no way of outrunning night as it falls across the landscape. Take a closer look at the first line of verse three and you’ll see how it doesn’t quite fall into the intended rhythm: and like a long black carpet. No matter how you try to pronounce this line, the word carpet refuses to end on a strong beat! By transforming a rising pattern into a falling one, especially at the moment that the unrolled carpet of night catches the speeding car, Cato uses rhythm to imply the impossibility of bending time to your will. Ultimately, the poem suggests that the most we can hope for are momentary illusions of victory over time, something explicitly acknowledged in the final stanza when the speaker admits: life and time are one. No matter how fast she goes, this truth is inescapable.

In fact, the speaker finds herself caught in something of a paradox; drive too slowly and the night will catch up with you; yet in the effort to escape, life can fly too fast. It reminds me of the old saying that ‘time flies when you’re having fun’. The speaker refuses to simply avoid death by hiding away; instead, she embraces life eagerly, with relish, gusto, bravery, and verve. Her helter-skelter, breakneck drive isn’t simply an attempt to hold onto life; maintaining her reckless velocity is the meaning of life, even if that means time passes swiftly. Rather than succumbing to despair over this, or over the inevitability of death, the speaker doubles down on her decision to throw herself into the future and chooses to embrace the day as fully as she can (poems that exhort readers to ‘seize the day’ or ‘appreciate the moment’ are appropriately called carpe diem poems). Whether you think this is foolish or fantastic really is down to you: the same number of people would probably choose to live as a lion for a single day as choose ten years as a mouse. At the end of the day, there’s no one-size-fits-all way to live your life, and different people will have their own way of seizing the moment. Noticeably, there’s no mention of other drivers in the poem; our speaker is alone on the road and gets to decide for herself. Her choice? Putting pedal to the metal, she hurtles forwards into the light and heat of the sun, an image that suggests a celebration of life’s possibilities as well as an acceptance of death’s inevitability. The poem’s effervescent energy is its own answer.

We might not be able to outrun time, but Cato’s speaker gives it a hell of a try. Like a cinematic hero choosing glorious death over ignominious surrender in the final scene, if annihilation is all that awaits at the end of the road, she meets it head on, unafraid.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Metamorphosis by Nancy Fotheringham Cato

An environmental activist and writer, Cato’s poems often present the world as a living entity. You may have sensed this at the margins of The Road, but it’s front and centre of Metamorphosis which explores the transformation of the speaker into a tree. Rooting herself firmly into the ground, the speaker is able to appreciate workings of the natural world, the passage of time, and the wheeling stars above.

- She Being Brand by e.e. cummings

In this famous poem about driving, cummings plays with form and structure to suggest the experience of being inside his brand new car for the first time. Ahem!

- Waterfall by Lauris Edmund

A poem about ageing, the passing of time and the distortion of memory. Above all, a gentle love poem written in the twilight of a life spent together.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Road at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the conventions of ballad poetry.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Nancy Fotheringham Cato’s beautiful ballad? Which image do you find most memorable from the poem? Would you choose to ‘seize the day’ and hurtle forwards regardless? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.