W.H. Auden takes us on a tour of a glittering city… and gives us a glimpse of the rot that lies beneath

“His poetry is concerned with moral issues and evidences a strong political, social, and psychological context”

Poetry Foundation

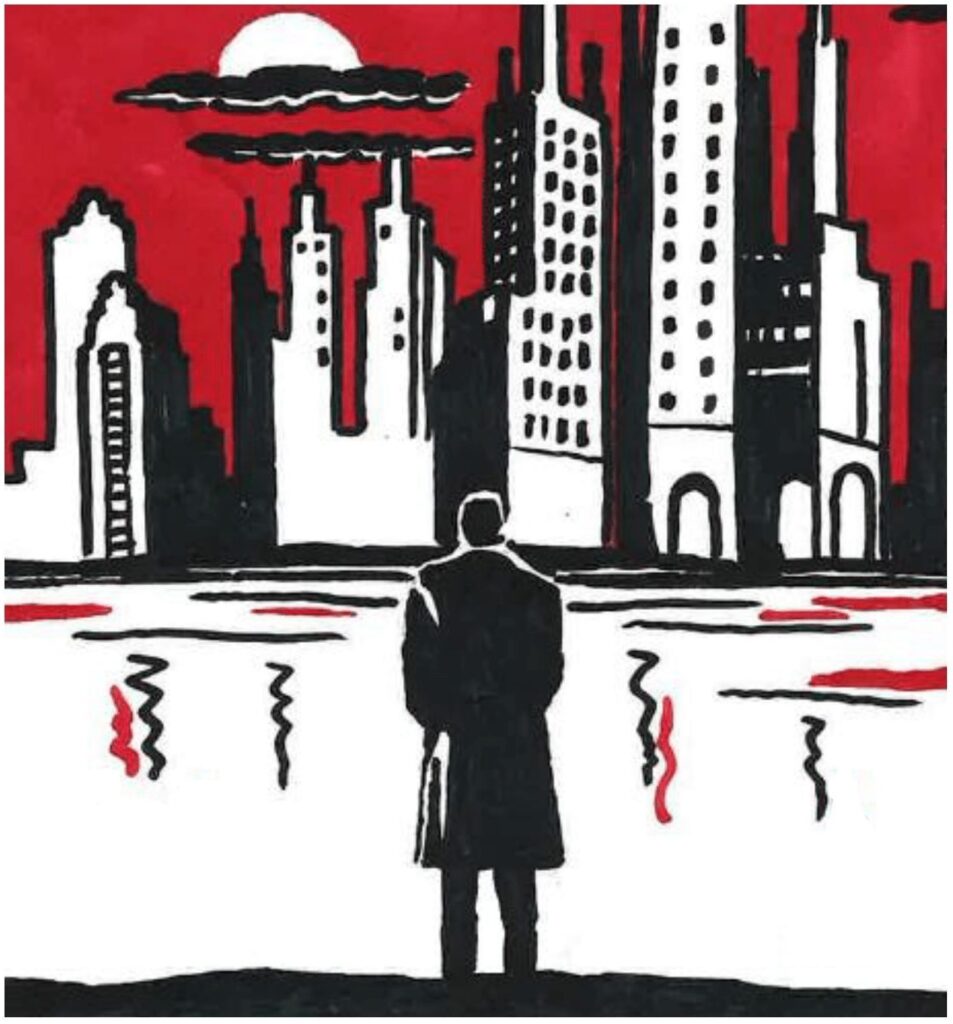

Cities are intrinsically contradictory, at once alluring, exciting, exploitative, and unforgiving. Above all, they promise riches; whether the cultural richness of art, theatre, nights at the orchestra, or the simple promise of making a million in the blink of an eye, the lure of the city is hard to resist. That ‘London streets are paved with gold’ is an enduring myth, suggesting one of the world’s most famous capitals is a place of opportunity. Derived from the Victorian tale of Dick Whittington and His Cat, anyone familiar with this story will know the irony that, on arriving in London, Dick and his feline friend found only filthy streets crammed with the poor and dispossessed. While Auden’s mysterious Capital is unnamed, standing in for any city that beckons to those who dream of a better life, echoing in the poem’s title is the association of ‘capital’ with money, a glittering, golden seduction. Yet Auden reveals that the city’s golden shine quickly rubs off. Beneath the gilded veneer, the grubby reality is that only a privileged few ever enjoy the city’s dubious pleasures. Everyone else gets chewed up and spat out in a place where people are disposable and dreams are crushed:

Quarter of pleasures where the rich are always waiting,

Waiting expensively for miracles to happen,

O little restaurant where the lovers eat each other

Café where exiles have established a malicious village;

You with your charm and apparatus have abolished

The strictness of winter and the spring’s compulsion

Far from your lights the outraged punitive father,

The dullness of mere obedience here is apparent.

Yet with orchestras and glances, O, you betray us

To belief in our infinite powers; and the innocent

Unobservant offender falls in a moment

Victim to the heart’s invisible furies.

In unlighted streets you hide away the appalling;

Factories where lives are made for a temporary use

Like collars or chairs, rooms where the lonely are battered

Slowly like pebbles into fortuitous shapes.

But the sky you illumine, your glow is visible far

Into the dark countryside, the enormous, the frozen,

Where, hinting at the forbidden like a wicked uncle,

Night after night to the farmer’s children you beckon.

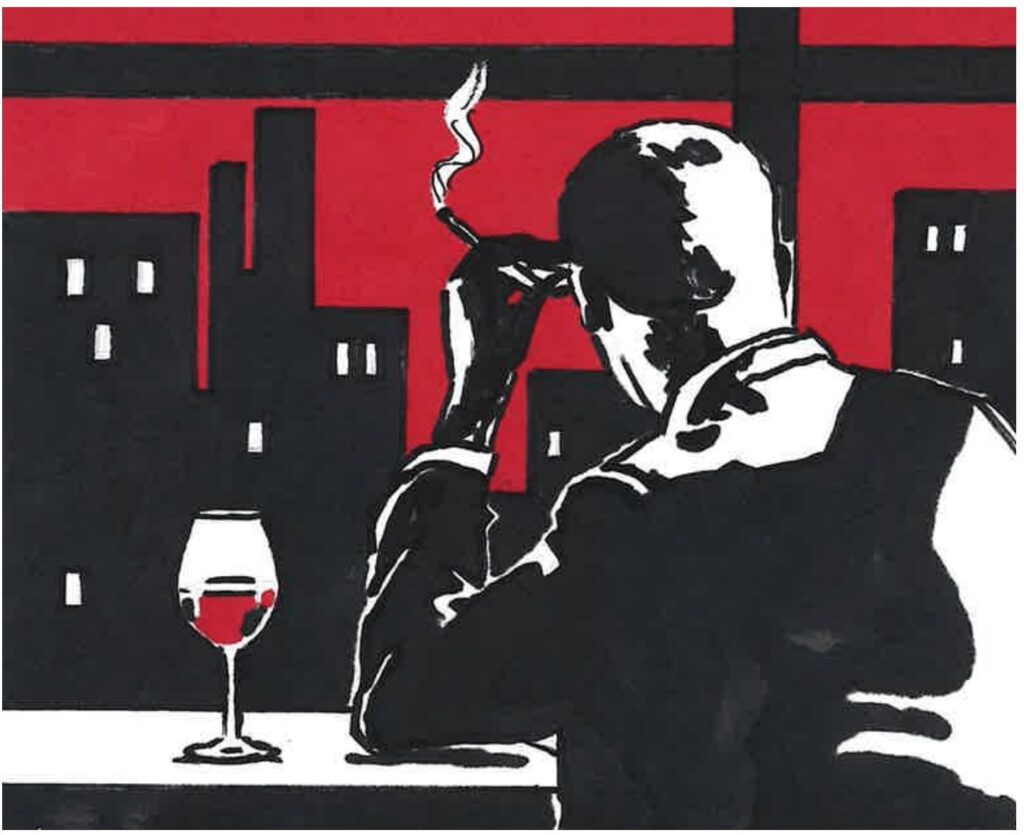

Auden’s unnamed city appears at first glance to be a glamorous place of decadence and luxury, stuffed full of the temptations of modern, cosmopolitan living: diction such as pleasures, rich, expensively, miracles, eat, lovers, charm suggest a sybaritic and hedonistic place where all one’s desires can be satiated. Emphasis is placed on physical and carnal pleasure; eating and drinking the night away in one of the city’s expensive restaurants is a pastime much to be savoured. A certain intimacy is established through words such as little, village, and café, suggesting a tight-knit, close community of exiles (people who’ve arrived from elsewhere and come together in the Capital). A sense of transgressive, forbidden activity is expressed through subtle flirting (glances) and suggestive imagery hinting at more explicit experiences (lovers eat each other). For the discerning consumer, more refined entertainment is provided by orchestras, no doubt performing in grand theatres. It seems that, in the city’s quarter of pleasures, there’s something for everyone to enjoy – if you’re rich enough to make it, that is – and the promise of a better life than the dull, repetitive routines of farmers’ children is impossible to resist.

While the lure of glamour and luxury are obvious siren calls to outsiders, Auden refers to equally important push-factors that motivate (especially) young men to leave their impoverished rural homes. Where the Capital is a place of ease and freedom, the countryside is the opposite; an oppressive place where young people live under the thumb of outraged punitive fathers. Shaped by custom and generations of poverty and toil, these farmers are angry, embittered, and expect nothing more than obedience from their children. Through juxtaposition, Auden creates the strong impression that the texture of life in the countryside completely contrasts with life in the city. Words like strictness, dullness, punitive and compulsion describe a tightly controlled, unstimulating life on the farm whereas life in the city seems magical by comparison, implied by words with fantastical associations like charm and miracles. Nowhere is this clearer than in the poem’s contrasting imagery. The country is a cold and frozen place, kept perpetually in the dark by entrenched traditions and endemic poverty. By contrast the city is a place of light, illuminated by modern streetlamps that abolish the strictness of winter, promising safety, warmth and prosperity for all. So bright shine the lights, powered by electricity, and the fires and forges of thousands upon thousands of workshops and factories, that the city glows like a beacon on the horizon, pulling in disenfranchised young people across enormous distances like moths to a flame.

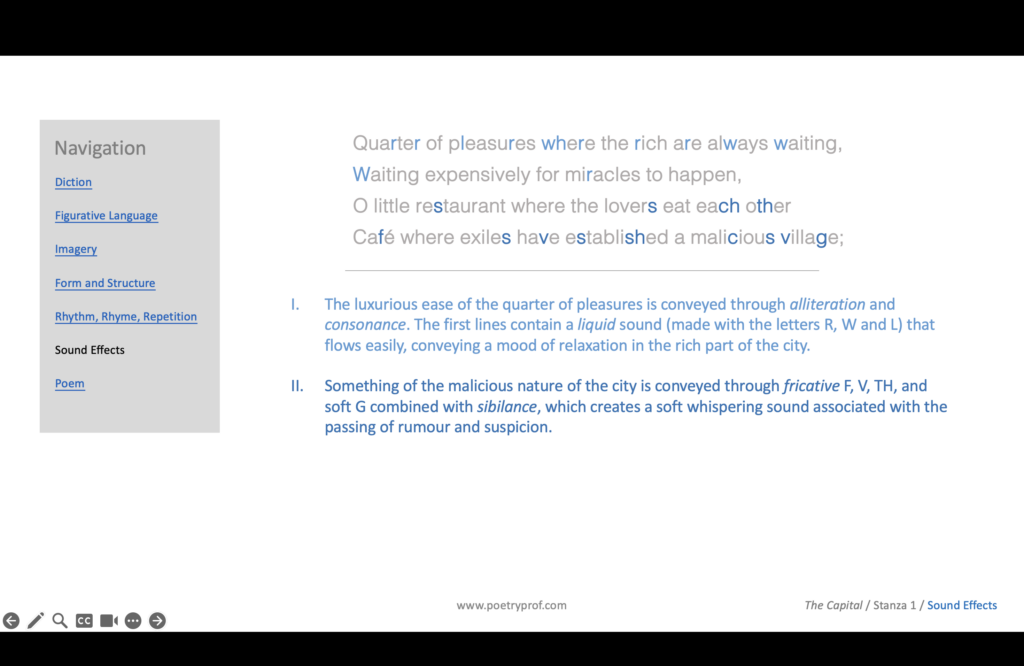

Poetically, the contrast between city and country extends to Auden’s use of sound. Woven throughout Auden’s poetry is an extremely subtle, but powerful, blend of consonance and alliteration that has us almost feeling the tug of the illicit (forbidden) pleasures of the city. Mostly, these lures are characterised by soft sounds associating with luxurious ease. You’re no doubt familiar with sibilance, which can be made with S, Sh and even Ch (the first line contains all of these sibilant sounds in the words pleasures, rich, always). Readers can all but feel rich decadence oozing off the page through liquid Rs, and Ws, sounds evoking the laziness of long, aimless days, and the woozy, boozy burning of money in fine restaurants, mixing drinks and sampling delicate foods. Try reading aloud the phrase where the rich are always waiting waiting to feel your mouth fill with thick, formless sounds that slosh round your tongue like fine wine. A master mixologist, Auden goes even further, blending in fricative F, V, Th and even soft G through words and phrases like lovers eat each other, cafe, malicious village. These combinations make the language feel sticky, intoxicating, making the Capital’s temptations palpable. On the other hand, when describing the dark countryside, Auden reaches for harder sounds such as guttural K and hard C, or plosive P (punitive, obedient, apparent). The contrast couldn’t be more stark so, for farmer’s children who’ve known nothing but brutal drudgery, it’s easy to envisage them slipping away in the night, heading for the big city and the promises of dreams coming true.

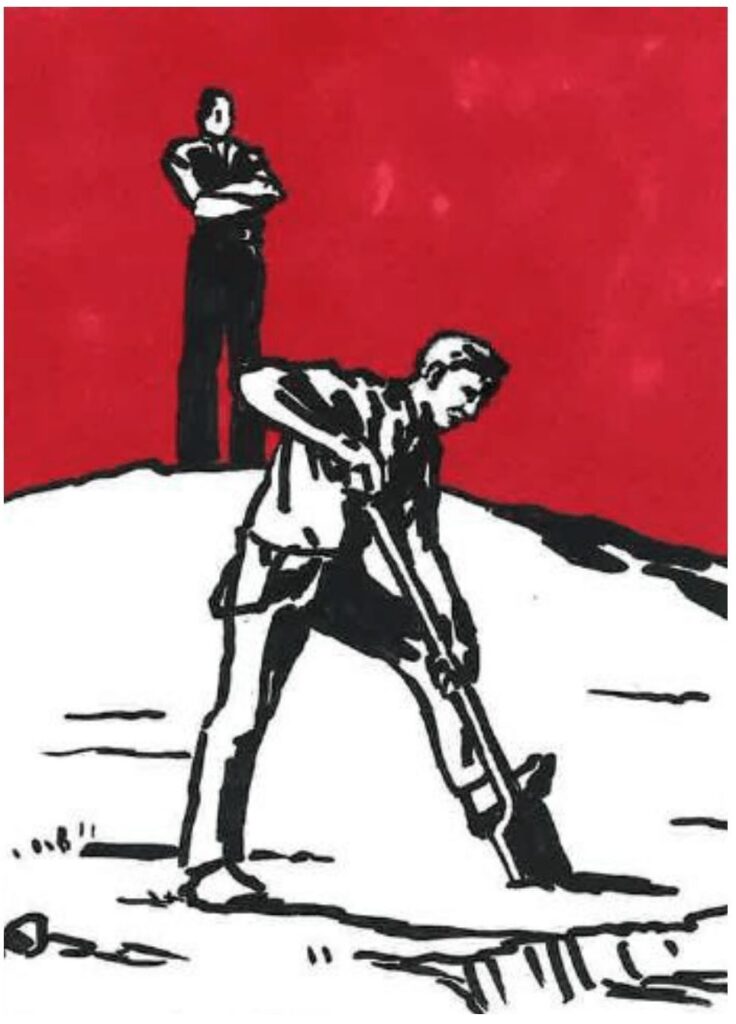

However, just like Dick Whittington who arrived to find London’s streets caked in grime, all is not as it seems in the superficially fabulous city. Scrape a little at the golden veneer, and the illusion peels away to reveal the grubby reality of life in the big smoke. For starters, the quarter of pleasures is closed to the vast majority of the newly-arrived. Gated and jealously guarded, the seemingly cosy café quarter is in reality a malicious village of selfish and spiteful elites who, idled in boredom (waiting waiting), spend their days vacuously gossiping, sniping, and breeding a mutual hatred of one another: the image of lovers who eat each other has a cannibalistic quality, suggesting people ‘prey on’ one another in an exploitative way. It gives this quarter of the city a selfish, brutal culture of one-upmanship and scheming rather than feeling like a close-knit community. The glamour of the city is a sham and the rich, lucky enough to live in the quarter of pleasures, are shallow and venal. As for the poor and those seeking work, they find themselves confined to a totally different part of the city, housed in dingy unlighted streets and forced to take menial jobs in factories, making disposable items for the rich to consume. Disillusionment is quick to set in: O, you betray us embellishes the realisation of broken promises and shattered dreams with an onomatopoeic cry. Those grand orchestras won’t play for them, nor will the rich exiles lay out the welcome mat. Rather, they’ve colonized the best cafes, pulling all the tables together to form a malicious village, jealously guarding what is theirs. Newly arrived in the city to find their fortunes, instead these unfortunates become victims to the heart’s invisible furies, perhaps referring to an ingrained sense of unfairness, suggesting it’s their own unrealistic hopes and dreams (belief in our infinite powers) that leads them astray. At one point Auden uses an oxymoronic phrase (innocent unobservant offenders) to imply how the combination of false promises with a naïve belief in get-rich-quick tales and an inability to see the truth suckers them in. Promised an escape from the drudgery of farm life, they are easily deceived; instead they are put to work and exploited the same as if they’d never left home in the first place.

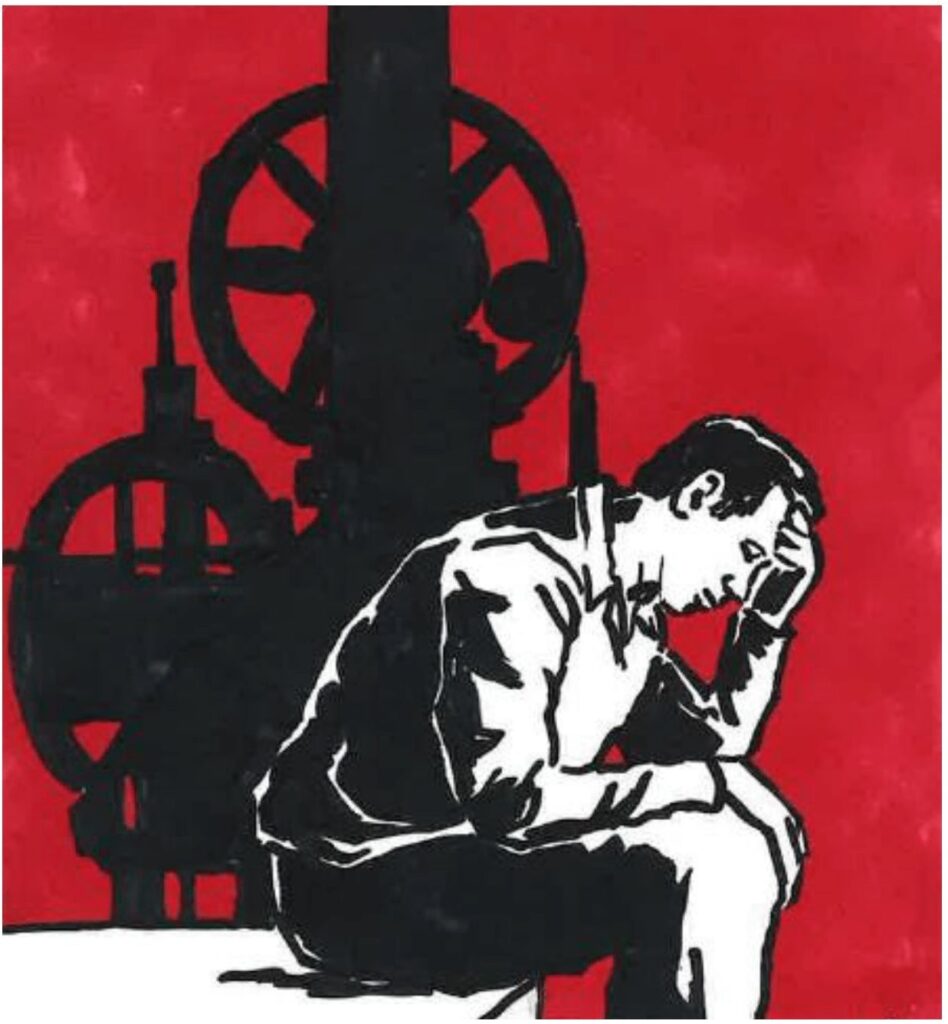

Auden is most explicitly angry when he describes the demeaning factory jobs that urban migrants are forced into. He’s disgusted both by the appalling conditions and the cynical hypocrisy of pulling the rug out from under people’s feet once it’s too late for them to go back. The fourth verse implies the dehumanising conditions in the city’s countless factories through figurative language that compares flesh and blood people to inanimate, cheap and disposable objects. Through simile, young workers are treated like collars or chairs, their lives remade by wealthy factory owners for temporary use into things that can be easily discarded once broken. In Auden’s time, a collar could be attached to and detached from the body of a shirt, so in this poem collars or chairs are symbols of how disposable these jobs – and the lives of people who work in them – really are. Given the powerful allure of the city, it’s easy to suppose that there’s a steady supply of young men and women arriving to replace those who fall ill or get injured or who run away from these hellish places. Auden uses the word battered to describe their experiences in terms of abuse, and the physical and emotional toll on people’s bodies and minds is expressed through another simile: like pebbles. In the sprawling industrial workspaces of the Capital, young people are ‘ground down’ until they no longer appear human, but inhabit fortuitous shapes, a description that objectifies them as less than human and more like the products they manufacture. Auden’s critical tone is sharpened by his use of consonance in stanza four, particularly in the variety of hard consonant sounds conveying something of the brutal violence of a migrant worker’s day to day existence: sounds in factories, collars, battered slowly like pebbles, fortuitous shapes pound the ears as if we’re right there in the midst of incessantly hammering manufacturing equipment. Extending beyond the workplace, the poem further implies that factory conditions have encompassed much of life and become the norm for everybody. So automated and industrialised has the city become, that even the laws of nature no longer apply: the natural cycle of day and night is banished by the twenty-four hour lights of industry and even the seasons have been abolished, so people no longer experience the coldness of winter or spring’s compulsion (a word related to ‘impulse,’ suggesting any spontaneity of feeling, any deeply felt desire, has been eradicated). Instead, we run on ‘factory time’ all year round, our clocks ticking to the pattern of shift changes and work schedules rather than following natural rhythms. Other diction throughout the poem possesses similarly heartless connotations: the word apparatus, for example, suggests a mechanical environment where anything of nature is reduced to a component part, used and abused till it’s worn out, then ruthlessly thrown away and replaced.

If people are reduced to bits and pieces of discarded refuse, ironically, the city itself is addressed in terms used for living people! Like emphasising a light colour by placing it alongside a dark, this inversion highlights the dehumanisation of real people by ascribing human qualities to something that totally lacks humanity and empathy instead. Throughout the poem, Auden speaks to the city itself using the personal pronouns you and your, such as you with your charms… as if the city is capable of smooth seduction. Similarly, he accuses the city (you hide away the appalling) of concealing evidence as if all this is a premeditated crime. Directly addressing something inanimate (or otherwise incapable of reply for reasons such as absence or death) as ‘you’ is a poetic technique known as apostrophe, and Auden uses this masterfully to imagine the whole city as a scheming, underhand conspirator who promises fun and freedom, only to enslave and exploit people for its own benefit. At the end of the poem, apostrophe morphs into overt personification when the city takes on the guise of a wicked uncle who beckons a crooked finger at the next generation of naïve children he wants to lure away. This image hearkens back to traditional fairy stories such as Hansel and Gretel, the Pied Piper of Hamelin, or Pinocchio, all featuring children in perilous situations tempted into danger by a devious adult figure; Auden even recruits the word wicked into his poem, alongside other fairytale diction such as the aforementioned charms and miracles, dark countryside, enormous, forbidden, and the like, giving his poem the allegorical feel of a fairy story where no one lives happily ever after.

Written in 1940, as the second world war accelerated urban migration, encouraging more and more people to move into manufacturing (at first to support the war effort, later to support the interests of ‘capital’), The Capital maintains its relevance in our twenty-first century world. Where more than half of all people alive live in cities, where the gap between rich and poor is wider than ever, where the 1% seem totally devoid of empathy and compassion, where workers suffer cruel and dystopian policies drawn up by those who see them as dispensable, Auden’s twisted fairy tale takes on the shape of reality more each day.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Unknown Citizen by W.H. Auden

Auden was a versatile poet who wrote in blank verse, rhymed verse, unrhymed verse, any kind of verse! His rhythmic skills are on display in this poem, describing a man who is said to have lived an exemplary life – but was he ever truly happy?

- Down On My Luck by A.R.D. Fairburn

In this great companion-piece to The Capital, New Zealand poet and former priest Fairburn writes about a person who, down on his luck, wanders aimlessly, hoping to find his way to the next stage in his life. In this powerfully angry poem, he tackles the issue of poverty and wonders at the corruption that allows so few to enrich themselves at the cost of so many.

- The City by C.P Cavafy

Unlike Auden’s poem, here’s one about a city that the speaker doesn’t ever want to leave. No matter how imperfect life is in the city, he feels it’s his home, and he knows it so intimately he can’t bring himself to find another. Perhaps Cavafy was writing about Alexandra in Egypt where he was born, and returned to later in his life.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Capital at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining personification and apostrophe.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of W.H. Auden’s poem? What’s your idea about the lure of the big city? How do the pungent and vivid images strike you? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.