Charles Swinburne says he’ll do anything for love – but does he mean it?

“In power of imagination and understanding he simply sweeps me away before him as a torrent does a pebble.”

John Ruskin (1819 – 1900)

If you’re a teenager sensitive to the pangs of young love, reading today’s poem might bring an embarrassed blush to your face. Charles Swinburne’s speaker sounds lovelorn, absolutely one-thousand-percent convinced that no-one else in the world could ever love someone as fervently, or feel the pain of rejection as bitterly, as he. He tries everything to seduce the unnamed object of his affections: songs, gifts, threatening to up-and-leave – even at one point considering suicide! If only he could somehow convince her of the sincerity of his love, she would be swept off her feet, blown away, her heart would melt… well, you get the picture. Actually, I wonder if older readers may also feel a touch of embarrassment, recognising their past selves in A Leave-Taking as well. Perhaps because it was all so new and fresh, love felt keener, disappointment more crushing – and self-pity more intense – than many might care to admit:

Let us go hence, my songs; she will not hear. Let us go hence together without fear; Keep silence now, for singing time is over, And over all old things and all things dear. She loves not you nor me as all we love her. Yea, though we sang as angels in her ear, She would not hear. Let us rise up and part; she will not know. Let us go seaward as the great winds go, Full of blown sand and foam; what help is here? There is no help, for all these things are so, And all the world is bitter as a tear. And how these things are, though ye strove to show, She would not know. Let us go home and hence; she will not weep. We gave love many dreams and days to keep, Flowers without scent, and fruits that would not grow, Saying ‘If thou wilt, thrust in thy sickle and reap.’ All is reaped now; no grass is left to mow; And we that sowed, though we all fell on sleep, She would not weep. Let us go hence and rest; she will not love. She shall not hear us if we sing hereof, Nor see love’s ways, how sore they are and steep. Come hence, let be, lie still; it is enough. Love is a barren sea, bitter and deep; And though she saw all heaven in flower above, She would not love. Let us give up, go down; she will not care. Though all the stars made gold of all the air, And the sea moving saw before it move One moon-flower making all the foam-flowers fair; Though all those waves went over us, and drove Deep down the stifling lips and drowning hair, She would not care. Let us go hence, go hence; she will not see. Sing all once more together, surely she, She too, remembering days and words that were, Will turn a little toward us, sighing; but we, We are hence, we are gone, as though we had not been there. Nay, and though all men seeing had pity on me, She would not see.

On first reading, A Leave-Taking seemed to me like a tender and sympathetic portrait of heart-break, a young man lamenting the sudden end of a love-affair. He does all he can to try to persuade the lady in the poem not to give up on him. I sympathised with his emotional suffering; she won’t hear him, won’t speak to him, won’t even glance in his direction, let alone weep a single tear of regret that he’s leaving. After all, most of us have suffered some kind of break-up at some point in our lives, and the end of a relationship can be a painful time. But – after a while it slowly dawned on me… this affair never even happened! He was so caught up in his dreams of passionate love that he never considered the object of his persuasions might have ideas of her own – ideas that don’t involve him. Regular readers of these blogs will be prepared for my warning not to assume the speaker and author of a poem are the same person, and I think this is the case here. Algernon Charles Swinburne was twenty-one years old when he wrote this poem; young enough to remember the foolish pain of rejection but old and smart enough to be embarrassed by the overwrought emotions of unrequited love.

Instead, Swinburne is caricaturing young men who lust after unattainable women, feel the pain of rejection particularly keenly – and complain about heart-break particularly loudly. He draws on the literary archetype of a Petrarchan lover, who has a long and exalted history. At the start of Romeo and Juliet, Romeo acts like a quintessential Petrarchan lover when he pines after Rosaline, a woman only seen from afar and whom he had never even spoken to! The origin of this archetype is a fourteenth century Italian sonneteer named Petrarch, who featured a beautiful – but unavailable – woman called Laura in his poems. The tone of A Leave-Taking makes me think that Swinburne is poking fun at this kind of self-important man; whether you interpret his satire as sharp and cutting or as gentle and sympathetic perhaps depends on how much of yourself, or those you know, you recognise in this portrait. The literary term bathos means to treat trivial or narrow concerns importantly and it’s this feeling that underpins the satire of A Leave-Taking. The way Swinburne’s speaker seems to think he’s god’s gift to the ladies (associating his songs and gifts with angels and heaven) is a pointed example of bathos.

This interpretation of the poem is supported by an analysis of form. A Leave-Taking is written in unusual seven-lined stanzas (called septets) of steady iambic pentameter, reminiscent of a heartbeat, but controlled rather than frantic. The first line of each stanza begins with an action on the part of the speaker (for example, let us go hence) that is completely ignored by the woman in the poem (e.g. she will not hear). The middle lines of each stanza elaborate in some way on the speaker’s actions and bruised emotions, before ending in an abrupt, clipped reiteration of her implacable resistance to his charms; in this case, She would not hear. The rhyme scheme is AABABAA, with five of the lines rhyming one way and only two lines rhyming another; if you use your mind’s eye to isolate the middle three lines you’ll see they form an envelope rhyme (BAB) with the two outside rhymes being kept apart by the line in the middle, for all the world like frustrated lovers never able to come together. Zoom out to the poem as a whole and you’ll notice that the interjection Yea that begins the sixth line of the first stanza is mirrored in the sixth line of the last stanza by Nay. Oppositions of one sort or another echo through the poem, most obviously in the duality between ‘him’ and ‘her.’ Other dualities include heaven above and deep down, singing and silence, sow and reap and more. As well, the lovely image of the moon scattering light across the surface of foamy waves is a reflection. Masterful elements of form such as these belie the melodramatic tone of the speaker and convey the impression that the speaker and the poet are not the same person – although they may once have been.

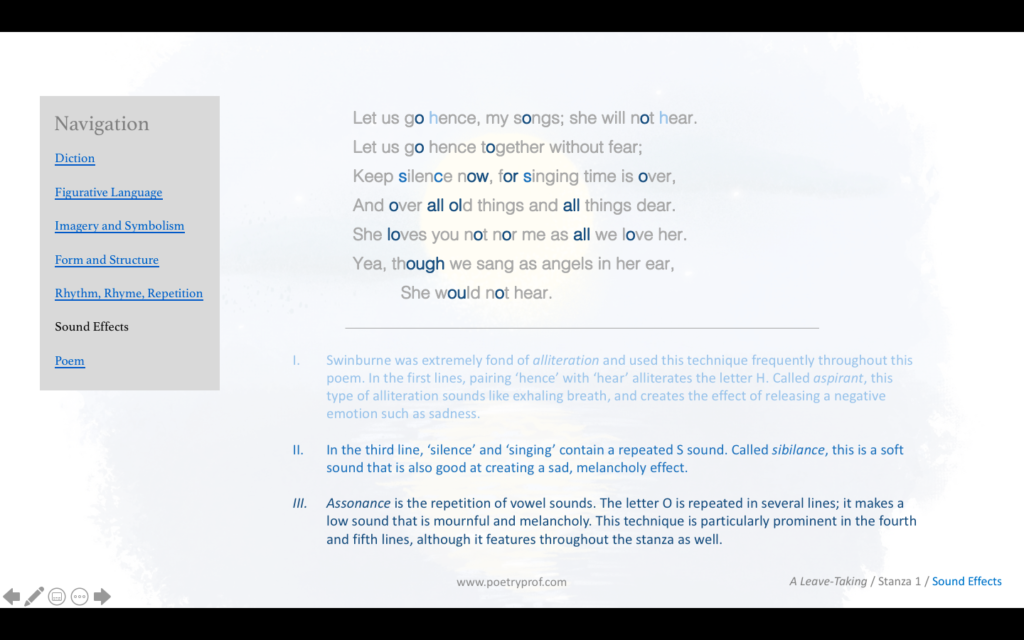

Part of what makes his tone of voice so bathetic is the way the speaker addresses himself alongside a third party, referring to both himself and another as us and we. And it’s amusing when the realisation dawns… this third party is actually his own singing voice, personified as a kind of wingman helping the speaker serenade the woman of his dreams! Thus, the poem opens with the instruction let us go hence… let us go hence together without fear. In my mind’s ear, although he’s speaking to himself, I imagine him saying these words just loud enough for her to overhear – a ploy by which he hopes she might suddenly come to her senses and cry out, “Stop! I do love you after all.” To be honest, I’m not sure he sounds like such a catch. Look how the first three lines all position verbs (let and keep) at the beginning; this is an example of the imperative tense, otherwise called the command tense, and it makes me think that the speaker is used to getting his own way. He certainly sounds confident – after all, he compares his own singing voice to the sound of angels! – but the mention of fear betrays a touch of insecurity, a burden carried by young men who act tough, but are only really looking for recognition. The personification of his singing voice plays into this idea as well, as if it’s his only companion – in reality he might be alone or even lonely. Sound transmits feelings of melancholy, especially softer sounds like sibilant S (silence, singing, sang, she) and assonance (the repetition of vowel sounds): phrases such as over all old things and she loves not you nor me contain long, deep assonant sounds that easily convey sadness.

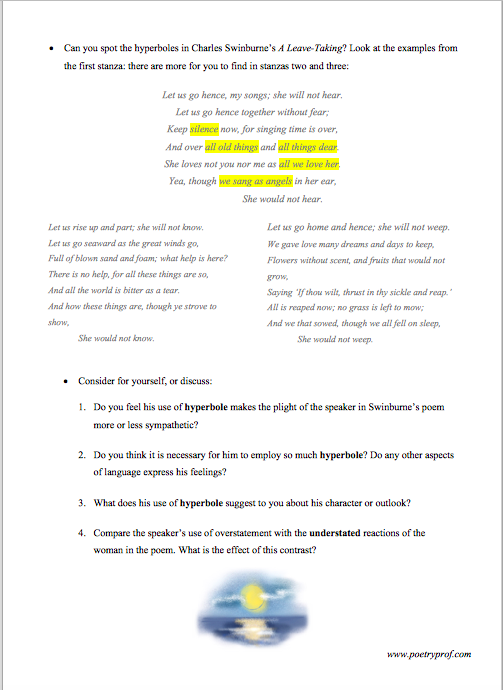

After his initial ploy fails to catch her attention, the speaker ups his game, commanding his voice to go seawards as the great winds blow. This is one of those lines that seems to be very knowing on the part of the writer. Swinburne deliberately aligns his speaker’s voice with the wind, describing it as full of blown sand and foam – in other words, full of bluster but without much substance. The syntax of this line reminds me of Shakespeare’s famous words ‘full of sound and fury, yet signifying nothing’. As well, the image of an intangible wind is one of those clues that suggests the entire relationship is imaginary – there’s no solid foundation for his protestations of love. There’s ample hyperbole in this verse: great winds… full of… no help.. all these things are so… all the world is bitter as a tear. Hyperbole is deliberate exaggeration, here crossing over into melodrama, which the speaker no doubt intends to be moving, but Swinburne wants us to hear as posturing: being melodramatic is one of the traits of a Petrarchan lover and hyperbole very often suggests a lack of emotional control or maturity. Skim your eyes over the whole poem to count the number of times the speaker uses the word all – you might be surprised how much hyperbole you can find. Technically though, Swinburne’s knowing, firm hand can always be sensed guiding the poem: a steady iambic rhythm, rhyme, and even the same sibilance / assonance combination that we heard at the end of the first stanza can be heard here: though ye strove to show, she would not know.

It’s in the third stanza where things start to get weird and where Swinburne seems to be having most fun with his Petrarchan caricature. Firstly, diction (dreams) makes explicit what we have been suspecting all along – this relationship is a one-way fantasy. The speaker mentions giving his love impossible gifts; flowers with no scent and fruit that will not grow, both images that suggest any tangible love affair never got off the ground. Swinburne develops the metaphor of the speaker planting (sow) ‘seeds’ of love that he expects her to harvest (reap); when she doesn’t do so he prostrates himself before her (I picture him down on his knees, arms wide open) and begs her to bury her sickle, a small curved knife used to cut plants, in his heart and cut it out for herself. Truth to tell, the use of language here is quite erotic, and I wonder if the associations with sexual penetration are completely intentional – the reversal of the usual male-female parts of the image would certainly play into the satire of a foolish young man who lets his thoughts and feelings – as well as his words – get out of hand. Where it does succeed is in the picture of abstract desperation it conjures; as with all his gifts and songs, she completely ignores him (She would not weep) and he’s left looking pretty ridiculous making all these grandiloquent gestures to the unresponsive air.

An aspect of this poem I really enjoy is the sense of irony that grows stanza by stanza. The more he says let us leave or let us go hence, the more I get the impression that he wants her to stop him from going. The more distance he threatens to put between himself and her, the closer he really wants to be. This irony is founded on repetitions of different kinds; in particular, anaphora and reiteration (repetition at the start of lines of poetry is called anaphora; a repetition of the same idea using different words is called reiteration); examples being let us go hence, let us rise up and let us go home, all of which essentially carry the same intentional meaning – ‘let’s get out of here’. Because of such frequent repetition, the poem is sometimes in danger of becoming a little one-note; you could certainly level this accusation against the fourth stanza which is almost a recap; she will not love… she shall not hear us… nor see love’s ways are all statements we have heard before. The same hyperbole characterises the speaker’s voice (though she saw all heaven in flower above… he really does think highly of his own gifts!), the same use of imperatives (come hence, let be, lie still). Repetition, though, is an effective way of encapsulating the Petrarchan lover’s propensity to wallow in the heightened pain of rejection. The fourth verse does develop the poem by introducing the lexical field of pain by describing the road to love as sore… and steep, equating love with pain using a beautiful metaphor: Love is a barren sea, bitter and deep. This is one of several lines where the poet’s craft emerges from beneath the bluster of speaker’s voice; Swinburne was especially partial to alliteration, and you can find plosive alliteration (made with the letters B and P) as well as dental (made with D and T) in this line. Both create hard, negative effects associated with pain.

An interesting thematic line of inquiry followed by this poem is whether or not you can make or force someone else to fall in love with you – how one person might move another. The speaker certainly thinks he can, and he spares no effort in his seductions, evidenced by the sheer number of verbs in the poem. He has sang songs, given gifts, strove with all his might. We saw him reap, sow and mow in quick succession. I’m sure you can find many more. All this action is designed to elicit a reaction, one that she steadfastly refuses to give. Therefore go hence, leave, part and even his threats to drown himself (go down) can, in my opinion, be taken with a pinch of salt; faced with her continued stoicism, he just keeps upping the stakes trying to get her to react. Contrast all his frantic activity with her passivity, characterised by frequent negation (she will not hear, she will not see, she will not weep, she would not care) and symbolised by the way the fruit he gives her would not grow, as if her stoicism extends even to the objects around her.

In the fifth stanza, her lack of reaction spurs the speaker to new levels of histrionics and hyperbole as he imagines giving up on love and life: Let us give up, go down; where go down means to throw himself into the ocean (I’ll admit, this verse prompted my own moment of reflective embarrassment, reminding me how, when I was younger, my teenage imagination conjured more and more fantastical ways to make ‘that girl’ over there notice me). He imagines the pathos of this scene would be enough to move even the moon and stars in the sky – so numerous they seem to paint the sky gold (made gold of all the air is another beautiful image, albeit one tinged with that familiar hyperbole) – but fail to have any effect on her at all: she would not care. The process of his imagined death is drawn out and surprisingly graphic, diction such as drove, stifling and drowning suggests that unrequited love can be both painful and suffocating: Though all those waves went over us, and drove Deep down the stifling lips and drowning hair. Swinburne once again treats us to a masterclass in the use of sound: the letters W, L and R belong to a category of alliteration called liquid, a perfect sonic accompaniment to a watery scene. Dental D and plosive P are once more pressed into service to suggest pain, and assonance (though all those, over, drove, down, drowning) underscores everything with a melancholy dirge. It’s at this point of the poem that you might find the attention-seeking tactics of the spurned young man ridiculous (especially if you interpret his drowning himself as just another attention-seeking ploy). But don’t allow any frustration at his behaviour to deafen you to Swinburne’s incredible poetry: stanza five gives us arguably the poem’s most beautiful image, when the moonlight transmits its own beauty (moon-flower) into the sparkles of light that ripple and play on the surface of the waves: making all the foam-flowers fair. As a metaphor for the transformative and potentially edifying power of love (symbolised by the ocean, remember) this is an extremely powerful image, enlivened by Swinburne’s trademark use of alliteration (fricative this time) which creates the soft sound of the sea’s susurrations.

Meatloaf memorably sang “I will do anything for love – but I won’t do that,” and, of course, the speaker doesn’t actually throw himself into the sea. Another trait of Petrarchan lovers is that they are rarely men of action; they are thoughtful and sensitive souls, prone to introspection and emotional soul-searching. They tend to exist in fantasy worlds and find reality hard to accept; after all, Shakespeare gave us our first glimpse of Romeo hiding out in the darkness of his parents’ sycamore grove, before he retreats to his bedroom where he locks the door and closes all the curtains so as not to face the ‘reality’ of the day. Swinburne’s speaker is no exception – even in the face of continued rejection he can’t help having his ‘what-if’ moment, which comes in the final stanza:

…surely she, She too, remembering days and words that were, Will turn a little toward us, sighing;

Just like Romeo, Swinburne’s young lover is over-the-top, but he’s also capable of some brilliant sounding poetry. By now, your ear is probably attuned to sibilance, liquid alliteration and assonance, which imbue these lines with a woozy, dreamy quality, as well as that undercurrent of melancholy. It’s another sign that Swinburne is always in control, despite the melodramatic character of his speaker. Take onomatopoeia (sighing), which is faint and insubstantial – like the speaker’s hopes for love – as another example. The word sighing is important for another reason too; it reveals that the woman in the poem is capable of emotion. If only she had seen him in time he would have been able to elicit an emotional reaction from her. It’s one of the few moments in the poem where her actions are not negated (the others being turn and remembering, also in the final stanza).

There’s time for one last cheesy twist in the tale: after ignoring him for so long, when she finally glances in his direction… the speaker says it’s too late! He’s already slipped below the surface of that barren sea: we are hence, we are gone, as though we had not been there. In Swinburne’s speaker’s imagination there was no other way for the story to end: you might find it strange, but Petrarchan lovers actually enjoy dwelling in the pain of unrequited love, so, like Juliet awakening just a few seconds too late to stop Romeo drinking poison, this final irony is fitting. It elevates what would otherwise be a regular boy-meets-girl romance into the stuff of tragedy. Here, we see the speaker secretly revelling in the attention and sympathy such a tragic story evokes: all men seeing had pity on me. The feeling that his actions are performative, that he is staging this scene for others to see and appreciate, is inescapable in this line and you might like to think of ‘seeing’ as the theme of the final stanza.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Dead Love by Algernon Charles Swinburne

Short, succinct, and more direct than A Leave-Taking, you’ll recognise the truncated final line that Swinburne likes to use in this poem too.

- Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare

A famous poem in the Petrarchan tradition, I bet you can recite the first couple of lines of this sonnet already.

- Sonnet 31 from Astrophil and Stella by Sir Philip Sidney

Swinburne was a student of the Elizabethan poets and he would certainly have been familiar with this famous poem about unrequited love. Just like A Leave-Taking, you can take the emotions here at face value, or you might think there’s an edge of satire in Sidney’s tone.

- Debt by Sara Teasdale

Petrarchan lovers are invariably men, but men don’t have a monopoly when it comes to the pain of unrequited love. This exquisite little poem by Sara Teasdale was first published in 1914.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying A Leave-Taking at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how Swinburne employs hyperbole in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you like this breakdown of Swinburne’s A Leave-Taking? Do you agree that Swinburne is satirising young men who love too keenly, or do you think his words are more genuine? Which is your favourite line or image? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Hi, thank you so much for the notes. They’ve been really helpful. I have one confusion after reading this – doesn’t liquid alliteration include only l and r? Here, you’ve included w in liquid alliteration too.

Hi,

Thanks for your comment. My reference point is Frances Mayes’ wonderful book The Discovery of Poetry. She writes about W as a liquid sound. I believe in phonics W is also liquid, although i’m not that familiar with phonics. It makes sense when you try to make the W and R sounds with your mouth, you can feel the mechanics are alike. I highly recommend this book, by the way.

Thanks for the response! I’ll definitely check out the book

Yo Doug! Me, myself and Dingyu are extremely delighted with the annotations made on this poem. We appreciate it. You are a magnificent man. Cheers.

Hi Ruben – nice to hear from you! I hope you’re doing well in your studies. Say ‘hi’ to Dingyu ;o)