Life is fast-paced and frenetic in Julius Chingono’s disturbing poem.

“He is a poet of Zimbabwe, saturated with strong feelings about that society and its predicaments, but whose distinctive voice I, a stranger, find persuasive and powerfully moving.”

Lionel Abrahams, South African novelist, essayist, and fellow poet

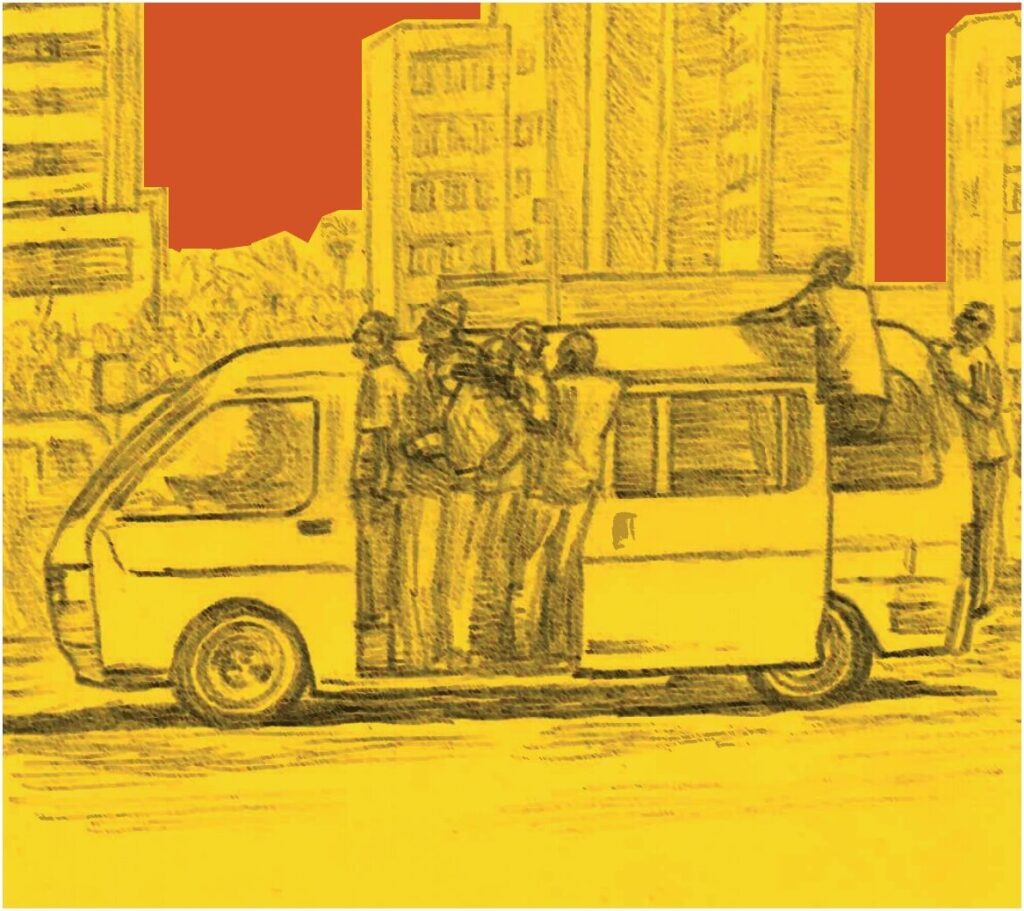

Today’s poem, in a happy coincidence, forms an unofficial trilogy of ‘Bus Poems’ alongside Sarah Jackson’s The Instant of my Death and The Bus by Arun Kolatkar, although to board Julius Chingono’s vehicle you have to hop from the Indian subcontinent over to Africa as Chingono is a poet from Zimbabwe’s capital city Harare. During his childhood, there was little functioning public transport infrastructure available for ordinary people. Instead, they relied on ‘kombis’, small buses and vans driven by entrepreneurial opportunists. Anyone familiar with the sci-fi show Sense8 will know the character of Capheus who began his story as a kombi driver. Of course, it can be chaotic and even dangerous to ride these unregulated buses – but they do perform a vital social function, knitting together the city and allowing tens of thousands of people to work, go to school, get to hospital, and access services across the city every day. Indeed, Zimbabwean blogger ensigntongs writes about kombi culture: “As much as we hate the way they drive, the rude manner of the drivers, and the garish stickers… they provide a vital function to the city”. That said, Chingono’s poem moves beyond the literal into the figurative realm, using the daily battle to board the bus as a metaphor for fighting through life in a chaotic society, where rules seem to exist in name only, and officialdom is either absent or complicit in making life harder than it needs to be:

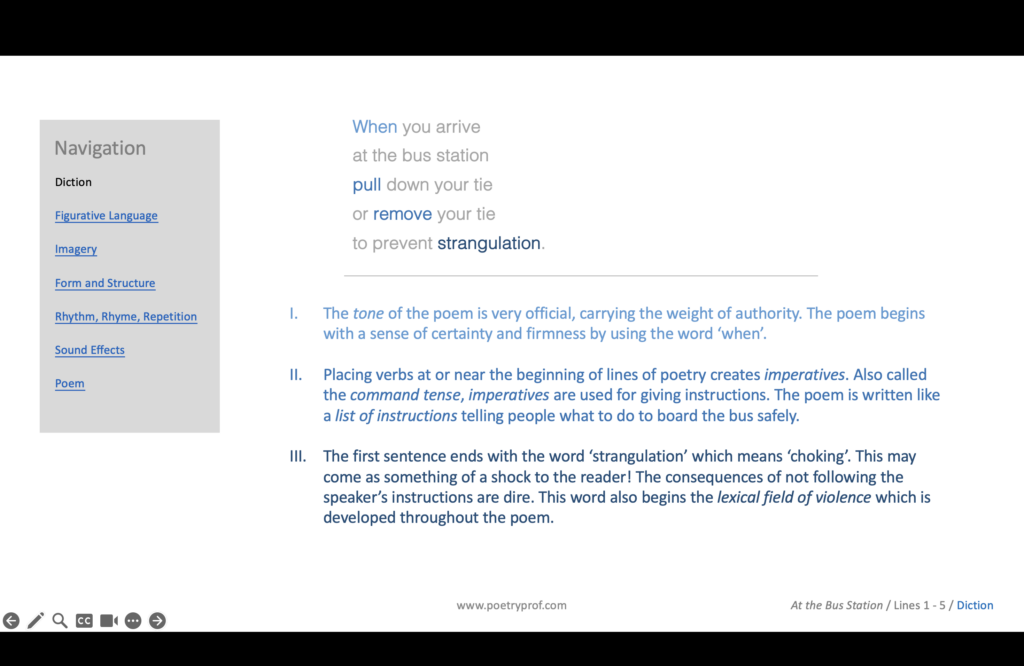

When you arrive

at the bus station

pull down your tie

or remove the tie

to prevent strangulation.

During the fight

to board the bus,

unfasten all buttons

of the shirt and jacket

to avoid losing the buttons.

During the battle

to gain entry

to the bus,

tighten both shoelaces

for, when you are hauled

into the bus,

you hang in the air

and the shoes may come off,

tighten your belt

to avoid being undressed

during the scrambling

at the door,

remove your spectacles

and hold tight to someone

until you are in the bus.

During the climb

pay no attention to human sounds,

also bear in mind

words lose meaning

until you are inside the bus.

Some poems are as much about the way they are written as the words themselves, and that’s certainly true of Chingono’s At the Bus Station. Written in one long narrow column, the poem visually resembles a queue of people squeezing themselves as tightly as possible into a narrow space. Chingono uses enjambment so that, instead of laying sentences out line by line in an organised way, they scramble down the page for several lines before a full stop gives a pause for breath. Some lines are as short as three words, and the visual impact is of cramming words into as small a space as possible. Just looking at the poem from afar, readers get a foretaste of claustrophobia, being jammed inside a kombi bus like sardines packed in a tin. I used to commute to work on the London Underground, so I can relate to this tight, squeezed situation; somehow, one last passenger always found a way to wriggle on, no matter how little space there seemed to be! Using layout on the page to create meaning in itself is called spatial form (or space) and this poem is a perfect example of how a reader’s mind is subconsciously prepared for the experience of reading in the few seconds it takes to focus one’s eyes on the first line.

Chingono’s poem can be read as an extended metaphor for coping with life in a chaotic society. He quite explicitly calls boarding the bus a fight, then a battle. These words, while being used metaphorically, are all too true if applied to a system or society that forces people to compete with one another to get anywhere (such as in the case of a chronically underfunded public transport system where demand far outstrips supply). People must be prepared to fight, to endure violence and expose themselves to danger, just to get a slice of a meagre pie. Those unprepared for battle face dire consequences: strangulation is the final word of the first sentence, coming as a bit of a shock the first time you read the poem. Disturbingly, the poem implies that violence begets violence: hold tight to someone and pay no attention to human sounds raise the uncomfortable possibility that, in order to get on board, one might have to be prepared to inflict violence on others. Scrambling suggests a mad rush of flailing limbs, and climb suggests the way up to the bus seats is longer and more dangerous than it should be. Elsewhere, the very language of the poem evokes the violent experience of battling for every inch of space on a crowded bus through use of sound, especially consonance. Words like pull down and tighten might not seem particularly violent on the face of things. But so many of the words in the poem begin with hard consonant sounds (alliteration, as in the example of pull… prevent…) or repeat hard consonants (consonance, such as the repeated letter T in tighten). The sheer frequency of these hard letters – especially plosive B and P alongside dental D and T – and clashing opposing consonant sounds together creates a sonic effect called cacophony: a discordant and disharmonic chaos of sound befitting the frenetic, scrambling images. You can find these sounds in lines such as To board the bus unfasten all buttons and During the battle… but, in truth, this technique is so prevalent that you can close your eyes, pick a line at random, and you’ll probably land on a disharmonic mix of hard consonant sounds suggesting pushing, punching, and jostling as passengers struggle against each other to climb into the bus.

In order to avoid unpleasant, even fatal, consequences, the poem presents a list of instructions that one must obey to successfully board the bus: for example, pull down your tie… tighten both shoelaces… remove your spectacles, all delivered in the imperative. Also called the command tense, this mode of address is formed by placing the verb at the start of a line. The list of commands gives the poem a firm tone; these are instructions that must be followed. However, it’s important to note that following the rules won’t help you escape violence. Each instruction is more about mitigating the worst consequences (like strangulation). In this way, the poem implies that violence is an inherent part of the system, the fight is certain. As the speaker says when you are hauled into the bus you hang in the air, the line is delivered in a way that all but promises the experience will be painful and possibly even fatal (the word hang, while deployed here to mean ‘suspended,’ has connotations of strangulation as well). Rather, the litany of instructions has the feel of ritual, the focus on details of clothing such as jacket, belts, buttons, spectacles, and shoelaces is suggestive of a soldier ritualistically strapping on armour, checking weapons, bracing for the onslaught. Written in the second person as if speaking directly to you, readers are made to feel the prickling anxiety of approaching violence as we wait in the calm before the storm for the scrambling to begin.

Gradually, Chingono builds the realisation that the normalisation of violence is tacitly approved of, and even enforced by, the systems around us. The ritualism of his language, as if the poem is being read by rote, mimics the calm, dispassionate tone of an official poster plastered at the bus station entrance, or an announcer speaking in a bored voice over a loudspeaker. Ironically, despite the number of active verbs, the impression comes across as one of passivity, as if both passengers and bus authorities fatalistically accept the inevitability of this process, as if going through this chaos is the only way to get on board. There’s never any glimpse of emotion in the station announcer’s voice; instead we can detect a tendency towards repetition that resembles the legalistic language of disclaimers (for instance: pull down your tie or remove your tie; tighten your shoelaces… tighten your belt). The journey into the bus is laid out in a meticulous step-by-step sequence (when you arrive… during the fight… during the battle… to board the bus… to gain entry to the bus… at the door… during the climb…) which covers all the bases from a legal point of view, but also helps build tension as the writer carefully ratchets up the pressure (tighten… tighten… tight… in particular, feels like turning the screw until the squeezing, claustrophobic pressure is unbearable). Chingono creates a disconnect between the indifferent tone of the speaker, who sounds bored, and the distressing images he describes. His detachment implies that violence is not just tolerated by but encoded in the system. The natural outcome of this is dehumanisation, something that happens at the end of the poem when passengers are instructed to pay no attention to human sounds, such as cries for help or screams of pain. It’s here that people become complicit in their own oppression. By pliantly following instructions, a person becomes a part of the system. What need have authorities to enforce rules if those oppressed can be manipulated into inflicting force on each other?

In truth, the seeds of dehumanisation are sown much earlier: instructions such as remove your tie, or unfasten all buttons, are designed to remove any little indicators of individuality, inculcating a herd mentality that turns individuals into a mob and by the time we reach the end of the poem, physically battered and emotionally bruised by Chingono’s violent imagery, we have entered a Kafkaesque reality where down is up and wrong is right. Many of the instructions seem irrelevant, or useless, or redundant; will unfastening all buttons really help avoid losing the buttons? This kind of confused logic has little to do with safety and more to do with creating the illusion of official accountability. When you think about it, the poem’s instructions are a recipe for violence disguised as a safety warning. Often, what is not said is more important than what is: in the example of losing the buttons, what he means is they might be ripped off. The same goes for being undressed, which not only hides the reality of having clothes torn and ripped in the crush, but covers up the disturbing possibility of sexual violence too. Human sounds might be anything from cries for help to screams of pain. You’re told to hold tight, but what happens if you let go? As the announcer admits at the end of the poem: words lose meaning until you are inside. If language is something that defines us as a species, this loss of language equates to the loss of our humanity.

The bus should be a communal, social space – but the behaviours needed to board the bus are purely selfish. Life is a rat-race, dog-eat-dog experience, and only those prepared to do what they have to do will survive.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Presidential Motorcade by Julius Chingono

A great counterpoint to At the Bus Station. Of course, while ordinary people struggle to board the crowded, underfunded public buses, politicians cruise past comfortably in blacked out limousines. A short and angry poem about corruption told through a young boy’s eyes.

- A Poem for Zimbabwe by Chenjerai Hove

There’s a rich tradition of poetry written in English from Zimbabwe, and this is one of the most famous examples. Hove has spent his life commenting on Zimbabwean society, even founding a newspaper from 2000 to 2002.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying At the Bus Station at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the difference between tone and mood.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Julius Chingono’s poem? How did you respond to the images of the poem? What’s your interpretation of ‘words lose all meaning’? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.