Lose yourself in Robert Browning’s twisted labyrinth.

“We may be friends always… & cannot be separated.”

Elizabeth Barret Browning, in a letter to Robert Browning, before they were married.

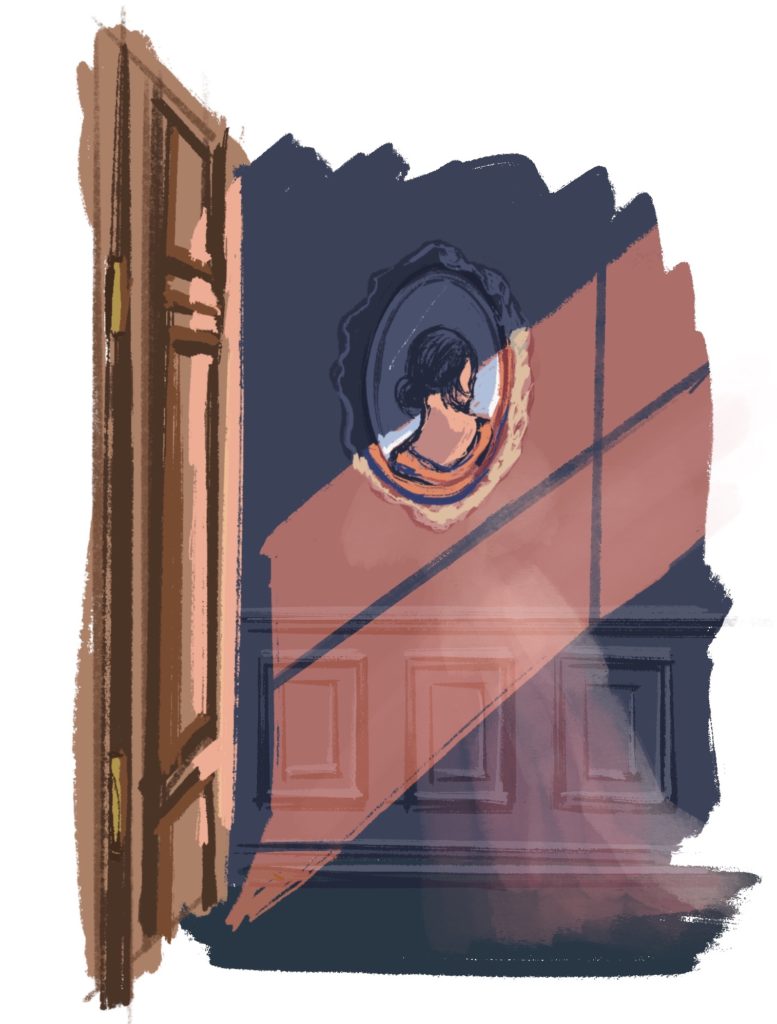

If you enjoy haunted house ghost stories, you’ll love today’s poem by Robert Browning. In the style of an Edgar Allan Poe gothic mystery, we meet a man who is looking for his wife. Presumably she’s just popped into another room for a moment. To begin with, his voice is full of confidence, as if he expects to find her. Fear nothing, he exhorts himself. But as time passes, and he continues to search through his sprawling – but empty – mansion, she’s always one step ahead of him, slipping out of the room as he bursts in, leaving only the faintest traces of her passing. Clues glimmer at the edges of perception: a gleam of light in the mirror, a faint whiff of perfume on the couch, a gently waving curtain. Will he ever find her? Read the poem and find out for yourself…

I Room after room, I hunt the house through We inhabit together. Heart, fear nothing, for, heart, thou shalt find her – Next time, herself! – not the trouble behind her Left in the curtain, the couch’s perfume! As she brushed it, the cornice wreath bloomed anew: Yon looking glass gleamed at the wave of her feather. II Yet the day wears, And door succeeds door; I try the fresh fortune – Range the wide house from the wing to the center. Still the same chance! She goes out as I enter. Spend my whole day in the quest, – who cares? But ‘tis twilight, you see, – with such suites to explore, Such closets to search, such alcoves to importune.

All the fun in this poem comes from the ambiguity. What has happened to the man’s wife? Where has she disappeared to? Is she still there, hiding in one of the house’s many rooms? Or has something more sinister happened to her? Perhaps all those years of reading Poe has prepared me for an unreliable speaker, because, as the man’s search continues indefinitely, I start to doubt his sanity – and perhaps even his honesty. He seems far too intent on his task, following the faintest of trails like a bloodhound coursing his prey. There’s a noticeable lack of concrete information about who exactly he’s looking for. I’m assuming it’s his wife, but the speaker only refers to she and her and gives us the barest clues such as, we inhabit together. Her name, the word ‘wife’, her position in the house? We find out nothing. The way he speaks to himself (heart, thou shalt find her) implies that, whoever she is, he’s been discombobulated by her sudden and inexplicable disappearance. Given that, for much of her life, Robert’s wife Elizabeth suffered from illness (he wrote this poem in 1855 while they were convalescing in Italy in a vain attempt to restore her health; Elizabeth would die in 1861) we can say with some conviction that the fear of loneliness and separation propels his desperate search and is the energy that fuels the poem.

Let’s return to that setting: an eerie house straight out of a Gothic nightmare. It sprawls ahead of the speaker like a vast labyrinth:

Room after room I hunt the house through We inhabit together. Heart, fear nothing, for, heart, thou shalt find her -

The sense of an endless, metaphysical mansion begins with the first line: room after room, as if the house stretches out in front of him as far as the mind can imagine. The impression of a twisting, turning maze is created through form: lines invariably enjamb (run on from one to the other without break or pause) or are fractured confusingly by caesura (deliberate breaks in the middle of lines or verses of poetry). I don’t think I’ve ever seen as many commas in a single line of poetry as in the fourth: Heart, fear nothing, for, heart, thou shalt find her – and to top it off, the whole line itself is isolated between two caesura; a full stop and a hyphen. The fractured and confusing punctuation reflects the speaker’s state of mind, thrown into sudden turmoil by his wife’s disappearance.

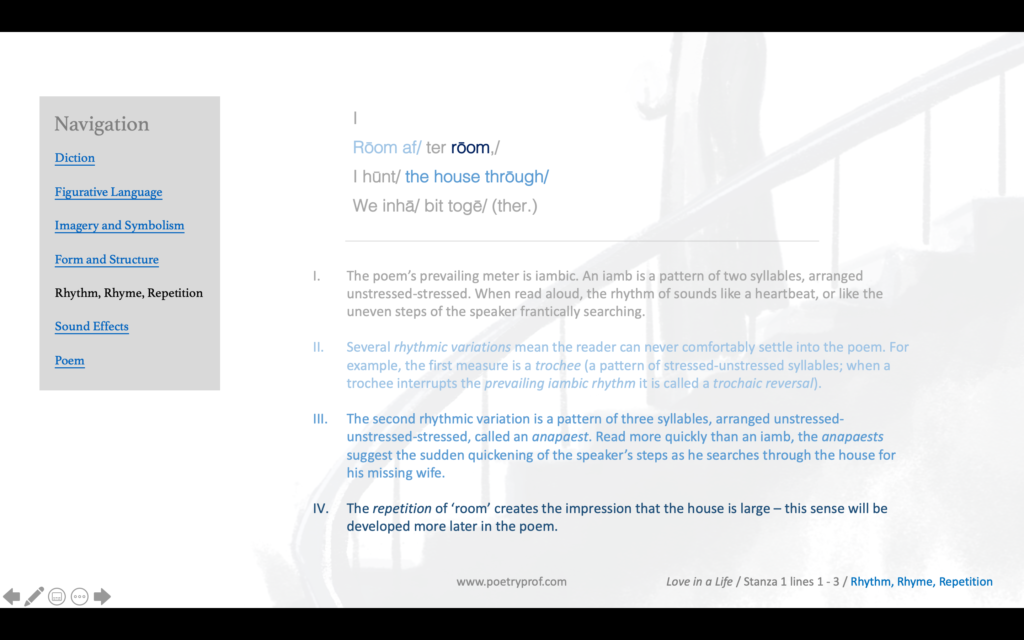

The poem is presented in two mirrored stanzas (it’s interesting that the word ‘stanza’ comes from Italian for ‘little room’; in this poem each stanza reflects the wings of the house) each of which begins with three short lines followed by five longer lines. Those first three shorter lines have two beats, so we call them dimeters; the rest of the lines in each stanza has four beats (tetrameters). The abrupt change between the third and fourth lines creates the sense of a sudden unfolding, as if the speaker is calmly checking one room with methodical actions – then suddenly uncoils, springing to his feet and rushing into the next. Alternatively, you might think the way the line suddenly lengthens reflects the physical distortions of the house; at several points in the poem physical space seems to shift dimensions, the house growing and spreading malevolently. Whether short or long, the prevailing meter of the lines is iambic; an iamb is a pattern of two syllables, the first of which is weak and the second strong. Throughout the poem, iambic rhythms brings to mind the speaker’s obsessive pacing as he marches from room to room, as well as the frantic beating of his lonely heart. The weak-strong duality of an iamb too suggests the poem’s central dynamic: the frantic, stressed husband searching for his invisible wife. Rhythmic variations include anapaests (measures of three syllables which create the effect of a sudden acceleration as he lurches from room to room) and trochaic reversals: read the phrases thou shalt find her and trouble behind her out loud to hear how the lines actually end on a weaker beat, undermining the confidence of his words and letting the element of doubt creep into the poem right from the very start.

Of what he might be afraid is a fair question to ask at this point. I’m always sceptical when a speaker or narrator exhorts himself to fear nothing; it sounds like he’s trying to convince himself he’s not afraid when he most certainly is. The repetition of heart plays into this point as well, as if he’s trying to lower his own racing pulse through force of will or persuasion. Directly addressing his own heart personifies it as something separate from himself, creating the impression that his body and emotions are not properly under his own control. Another detail from the same line: the modal shalt (a variant of ‘shall’) means ‘will’ and refers to a future in which the outcome is certain (thou shalt find her). Modal verbs express degrees of certainty or strength of feeling and shalt is on the strong side – too strong, in fact. It’s another example of the speaker trying to convince himself of something that is, actually, far from certain. The possibility of his search ending in failure, despite his protestations to the contrary, is a fear that will drive his actions right up until the end of the poem – and beyond.

Browning’s speaker hovers on the edge of reason and insanity, an impression borne out by some peculiar uses of diction in the early part of the poem (diction refers to the writer’s deliberate choice of words). Firstly, the word hunt is incongruous, more suited to describing that bloodhound with the scent of prey in his nostrils than a man casually looking through an ordinary house for his wife. One doesn’t innocently hunt a wife, one ‘looks’ or ‘searches’ for her. In stanza two the word ranged achieves a similar effect; it’s a verb that suggests an expansive hunt through open fields rather than a search through an ordinary house, no matter how wide it might be. The word through subtly alters the feeling of the opening lines as well, with its connotations of ‘thoroughness,’ as if he’s leaving no stone unturned, no nook or cranny unchecked. Perhaps it’s this word which sows the first thematic seed of obsession – or premature grief? – into the poem? There’s a definite ambiguity in the speaker’s phrasing in the opening sentence, especially in the juxtaposition of I and we in the same position on subsequent lines. The singular I suggests he’s alone in the house, while plural we implies there is more than one: which is it? There’s something odd about the choice of word inhabit, too, which comes across a little off-kilter. Think about the alternatives: ‘live together’, ‘dwell’ or even ‘reside’ aren’t quite as clinical or cold. Inhabit is just that tiny bit uncomfortable. But Browning doesn’t want you to feel comfortable – he wants that little shiver down your spine, the queer feeling that something isn’t quite right, and that the house, or the speaker – or both – are strange… or suffering.

The unusual and disturbing atmosphere of the opening lines is amplified by sound. Right from the outset, Browning employs a particular type of alliteration called aspirant. Made with H sounds (hunt, house, inhabit, heart, heart, her, herself, behind), aspirant mimics the sound of breathing, the sweaty panting and snuffling of the speaker’s hunt through the empty rooms. At the same time, the faint wisps of aspirant also suggest the hint of a ghostly, insubstantial presence that may or may not be sharing the house with him. Other sounds – particularly long assonant OO sounds (room, room , through, thou, bloomed) – are eerie and haunting, effortlessly evoking the spooky, atmosphere of a Gothic mansion that may be haunted.

The first stanza ends with a sequence of vague images that convey the faintest of sensory impressions – as if she passed through the room just moments before him, always one step ahead and just out of sight:

– not the trouble behind her Left in the curtain, the couch’s perfume! As she brushed it, the cornice wreath bloomed anew: Yon looking glass gleamed at the wave of her feather.

I read the word trouble to mean ‘disturbance’ – suggesting the way a still atmosphere can carry the impression of someone passing through moments before, even if she’s not there now. The mention of a curtain is straight out of the Gothic horror playbook; as he runs in the room is empty – except for the almost imperceptible swaying of the curtain. Has someone left a window open, or does it mark the passing of a person sweeping hastily by? Browning mixes sensory images to maintain that delicate impression of ‘something’ hovering on the edge of perception, never quite materialising into view. One moment there is a vague abstract impression (trouble left in the curtain); the next moment he catches a whiff of perfume from the couch, as if she just got up and left. Later he thinks he detects a gleam in the mirror, a faint visual clue, again straight out of Horror-101. How many movies have you seen where someone looks in a mirror only to doubt that what they see is real? Mixing up or moving rapidly from one type of sense perception to another is a technique known as synaesthesia (perfume is perceived by smell; light gleamed in the mirror is visual; brushed and the wave of her feather are both tactile and kinaesthetic). On one hand, the thick mixture of sensory images gives the impression that his wife is (was?) the one who brings life to the house, particularly in the phrase bloomed anew. On the other… I don’t know about you, but this part of the poem makes me feel like the house itself is alive – and is tempting him ever deeper into its depths by leaving a trail of clues for him to follow. Techniques we’ve seen before maintain the poem’s unpredictable feel; for example, caesura (made with a colon and an exclamation mark) keeps us always off-balance; hard guttural alliteration (curtain couch, cornice, glass, gleamed) hint at something malign hidden in the darkness; diction such as yon looking glass implies the mirror is waaaaaaay over there, on the far side of a bizarrely large room…

As the speaker’s search continues, the suspicion that there’s nobody there to find becomes stronger and stronger. Concrete images of the kind we’ve just discussed vanish from the second stanza, as a ghost or spirit might simply dissolve away. Halfway through stanza two, I’m convinced of the house’s hostility and the success of the trap it has laid. In defiance of natural or physical laws, the dimensions of the house grow: rooms and rooms is reiterated by doors and doors and the speaker’s journey takes him ever inwards from the wings to the center. Yet, no matter how far he goes, he never reaches the middle of the house. Remember how the switch between shorter and longer lines alters the dimensions of the house? Spatial form (or shape) is when the very layout of the words on the page implies meaning. It’s like Browning’s speaker is stuck on a moving escalator; the house expands at the same speed he runs so he never gets anywhere. Time is similarly illogical: yet the day wears, spend the whole day and twilight suspend the speaker in a grey limbo that is perpetually fading away.

The little phrase – who cares? marks the moment the speaker finally rejects any remaining rationality: twilight signals the end of the day and it’s time to rest, but he’s consumed by his obsessive need to track down his wife. He thinks he’s barely one step behind (she goes out as I enter) and the house has him convinced that, if he only moves that little bit faster, he’ll catch her. You’ll have noticed that the hunt has become a quest: the use of this word alludes to other doomed literary quests (such as King Arthur’s futile search for the Holy Grail. We all know how that turned out: Arthur’s obsession ultimately brought about the downfall of his kingdom and his own death).

The poem twists and turns back on itself so far that the borders between reality and madness finally disappear. The end of the poem reminds me of one of those old anthology horror TV shows that explore the outer reaches of the human psyche, like an episode of The Twilight Zone. The camera pulls out and the man becomes smaller and smaller until he’s lost in the twisting, maze-like corridors of his ever-expanding mansion. He disappears into the darkness telling us that he’s going to keep searching:

- with such suites to explore, Such closets to search, such alcoves to importune.

Rooms have multiplied into suites, closets and alcoves. His hunt has become an ‘exploration,’ as if he’s discovering hidden places that he’s never been to before. The triple repetition of such suggests he’s fallen into an ever-increasing vastness. Despite all the rhythmic variations in the poem until now, the final phrases actually reinforce the prevailing iambic rhythm. It’s as if the speaker fixes his determination – or obsession – unerringly on the goal of finding his wife. We’re left the impression that he isn’t going to give up, no matter how long the search will take. Importune is an interesting word, meaning ‘to beg’ or ‘to plead.’ Finally, the house is directly personified, exercising its macabre power over the speaker, luring him ever onward into the maze of corridors. It’s also a strange, polysyllabic word that creates the effect of the poem ‘fading out,’ as the speaker vanishes into the distance, madly intent on his futile quest. By this time, the house resembles an Escher painting – breaking all laws of reality and becoming a symbol for madness, obsession, or fear of loneliness. We might fairly ask: is his wife really there or is she simply a figment of his imagination? Has she long since died? What’s motivating his desperate search: loneliness, sorrow, guilt?

The poem offers up all these possibilities and more, while keeping the answers always hidden in the shadows, just out of sight…

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Haunted Palace by Edgar Allan Poe

This poem is a perfect companion-piece to Browning’s Love in a Life. Poe draws parallels between the rotting structure of an ancient house and the fractured psychology of its inhabitants. Read it at night by torchlight!

- The Listeners by Walter de la Mere

His children asked him to write them a scary bedtime story – so Walter gave them this haunting and mysterious poem about a lonely house hidden deep in the moonlit forest. Nobody answers the door… but you can feel the eerie Listeners peering silently out through ghostly windows.

- Ghost House by Robert Frost

Frost’s speaker visits the site of a lonely house that vanished many a summer ago. As he sits and speaks, the house becomes more vital and alive with every passing verse, until he can even feel the ghosts of those who used to live there sitting by his side.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Love in a Life at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the atmosphere / mood of the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Robert Browning’s Love In a Life? What do you think happened to the speaker’s vanished wife? Were you as creeped out as me by the mysterious house? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Would love to get your take on Browning’s “Last Ride Together,” tho it may be too much for high school.