Why Hone Tuwhare likes working near a door.

“…music grows flows

Apirana Taylor, (Poem to Hone Tuwhare)

grumbles and laughs

from his pen…”

Ask a New Zealander to name a favourite poet and chances are they will reply ‘Hone Tuwhare’. In 2003 he was named as one of New Zealand’s ten greatest living poets (although he since passed away in 2008). His poems regularly feature in the public eye, most notably his poem Rain (the clear winner in a 2007 nation’s favourite poem poll). Tuwhare was born into the Maori Ngapuhi tribe in 1922; he lived in Auckland and, later in his life, the Catlins, a rugged coastal area far to the south of the country. His father was a Maori speaker (Tuwhare also speaks Maori) and his love of oration can be seen in the form of this poem: a dramatic monologue, inspired by his time working in the Otahuhu Railway Workshop (1939 – 44). When heard reading aloud, Tuwhare performed this monologue in the voice of a Scottish steelworker. It’s probable that the character in the poem is based on somebody he used to work alongside:

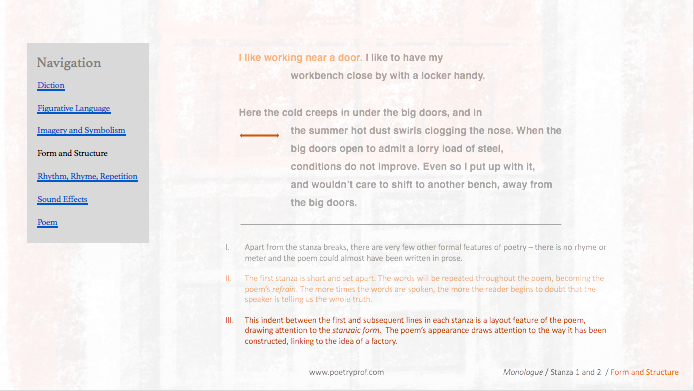

I like working near a door. I like to have my work-bench

close by, with a locker handy.

Here the cold creeps in under the big doors, and in the

summer hot dust swirls, clogging the nose. When the

big doors open to admit a lorry-load of steel,

conditions do not improve. Even so, I put up with it,

and wouldn’t care to shift to another bench, away from

the big doors.

As one may imagine this is a noisy place with smoke

rising, machines thumping and thrusting, people

kneading, shaping and putting things together.

Because I am nearest to the big doors I am the farthest

away from those who have come down to shout

instructions in my ear.

I am the first to greet strangers who drift in through the

open doors looking for work. I give them as much

information as they require, direct them to the offices,

and acknowledge the casual recognition that one

worker signs to another.

I can always tell the look on the faces of the successful

ones as they hurry away. The look on the faces of the

unlucky I know also, but cannot easily forget.

I have worked here for fifteen months.

It’s too good to last.

Orders will fall off

and there will be a reduction in staff.

More people than we can cope with will

be brought in from other lands:

people who are also looking

for something more real, more lasting,

more permanent maybe, than dying….

I really ought to be looking for another job

before the axe falls.

These thoughts I push away, I think that I am lucky

to have a position by the big doors which open out

to a short alley leading to the main street; console

myself that if the worst happened I at least would

have no great distance to carry my gear and tool-box

off the premises.

I always like working near a door. I always look for a

work-bench hard by – in case an earthquake

occurs, and fire breaks out, you know?

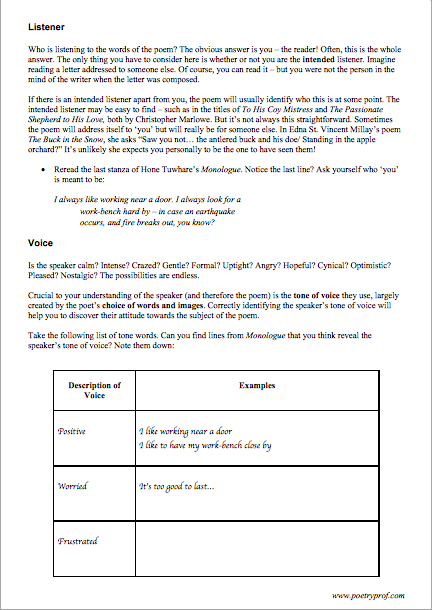

The title, Monologue, is from Greek: mono- means ‘solitary’ or ‘alone’ and –logue means ‘speech’. On stage, a monologue is a long, uninterrupted speech by a single character which reveals inner thoughts and feelings. It is particularly associated with ancient Greek and Roman theatre and not, as in this case, with the thoughts of a Scotsman in a steelworks. Through this grandiose title, Tuwhare reminds us that ‘high’ culture is not only the domain of a privileged few. All people, regardless of provenance or occupation, are entitled to poetry. This is an apt thought, as it soon becomes clear that while our speaker’s need for a job is being met, any other desires he may have are lost in the noisy smoke clogging the factory floor. Strangers and workmates are often competitors for the few available jobs, which are declining in number. His supervisors are unsympathetic, faceless men: they only come down to the factory floor when they want to shout their instructions in a man’s ear.

The speaker’s true attitude towards his life is difficult to ascertain because, for most of the poem, he is reluctant to say what he really means. This is a guy who is used to saying and doing what he has to do in order to stay in his job. No matter how bad the conditions in which he has to work, they are better than the alternative: unemployment. This word seethes beneath the surface of the poem without ever being uttered. At one point he euphemistically says if the worst happens. He also brings up the possibilities of an earthquake or a fire in an attempt to convince himself there are worse things than losing his job. By the end of the poem, I’m not sure he’s succeeded in tricking himself or us. Nor am I convinced by his repeated assertion that: I like to work near a door.

The doors are the poems’ central symbol and unpicking what they stand for is the key to understanding the speaker’s emotions. Do they represent a route to freedom or are they the means to his entrapment? Well, it’s a bit of both. On one hand he is near enough to the doors that if the worst happens – meaning he gets laid off – he can take his stuff (he makes sure to have a locker handy) and slip out. Each time they open to admit a lorry load of steel the infernal conditions actually worsen – but this is a price he is willing to pay to be close enough to the freedom he hankers for. On the other hand, the doors provide a kind of security: job security. When the cold creeps in his fear of what lies outside is emphasised by guttural alliteration. An incidental benefit – being near the doors provides distance from his horrible bosses! What the poem suggests is that, for some people, being in the steelworks is a necessary evil.

Informed by his own workshop experience, Tuwhare easily depicts the difficult working conditions in a steelworks – in winter cold creeps in; in summer hot dust swirls. The juxtaposition of two extremes leads us to believe there is never a comfortable time. The second and third stanzas reveal a deafening environment in which nature is suppressed (pointedly implied by clogging the nose) and people are subsumed to the rhythm of machinery: smoke rising, machines thumping and thrusting, people kneading, shaping and putting things together. In these lines, alliteration favours hard plosive P and dental D and T sounds, good for communicating negative feelings. But there is also a touch of guttural (G and CK sounds) and even sibilance (S, SH). Mixing lots of hard consonants together creates cacophony, a brilliant way of conjuring the oppressive noise of the factory floor. Look too how the little word people is almost hidden inside the list of verbs, as if human individuals are subsumed by the machinery.

As mentioned already, his supervisors are unsympathetic. Their inability to soften harsh news is highlighted by the entirety of stanza 5; an anecdote of men who come in looking for work and leave with their successes and failures writ large on their faces. Repetition of the looks on their faces suggests to me that the speaker can empathise: he knows what it’s like to be in their situation and not get that desperately needed job. Despite this, he is clipped and formal with these guests. The phrase As much information as they require suggests he will help them only to the extent that etiquette demands. While he recognises their plight, he can’t do too much lest their employment threatens his own precarious position.

This precariousness is all-too evident in stanza 6, when the speaker admits to us and to himself that it’s too good to last. This is the only time where he’s really being honest with us. The next few lines unspool a chain of events: orders will fall off, there will be a reduction in staff, more people… will be brought in. The modal verb will is important: the job of a modal verb is to express degrees of certainty or strength of feeling. Repeating ‘will’ three times indicates the certainty of these events coming true. The chain of events ends with an inevitable-sounding: the axe falls. Before this though, the speaker waxes philosophical about itinerancy (moving around to find work). What drives people to migrate from other lands in search of a new job and a new life? Our speaker can’t quite put his finger on it, so he expresses it in abstract terms:

People who are also looking

for something more real, more lasting,

more permanent maybe, than dying….

Tuwhare neatly positions two lists next to each other. The first list is cause-and-effect as falling orders leads to a reduction of staff and so on; the second list meanders from real to lasting to dying. The structure mirrors his mind grasping at what it is itinerant men are searching for. Anyone who has felt trapped in their circumstances can probably recognise the yearning behind these lines, expressed through the repetition of ‘more… more… more…’. Both lists end the same, although the expression is different: dying / the axe falls. Tuwhare neatly conflates a man’s entire life with his job and suggests that some workers – particularly manual workers – are only allowed to find meaning and worth in life through employment.

Afraid of where this train of thought might take him, the worker pushes it away and returns to his previous assertions: I think that I am lucky to have a position by the big doors. He imagines how the doors connect to the alley and the main street outside in a way that betrays his hankering for freedom. By now, the reader is getting a handle on his tone of voice: when he says ‘I am lucky’ or ‘I like’ we hear the notes of resignation he wants to hide. When he sounds upbeat, we hear how he is forcing positivity into his voice. As the speaker says in line 36, he’s trying to console himself. By the time the final stanza comes around and he repeats I always like working near a door he’s fooling nobody. The poem ends with a colloquial phrase, you know?– the question hints at the presence of a listener to whom the speaker is appealing for confirmation or reassurance. His true feelings can be felt in the language he uses: the axe falls equates unemployment with dying; I put up with it and it’s too good to last are rare honest glimpses; the little word ‘always’ slipped into the last verse – twice – reveals that he’s been moved on before and likely will again.

Monologue as a whole is an example of Tuwhare’s distinctive style: it’s a ‘conversational poem’, containing narrative elements with subtle variations of tone, humour, pathos and intimacy. This was not his only time writing a monologue: in New Zealand one of his most famous poems is the brilliantly-named To A Maori Figure Cast in Bronze outside the Chief Post Office, Auckland. Also written as a dramatic monologue it mixes English and Maori idioms, making it tricky in places for overseas readers to understand. Thankfully, Monologue doesn’t rely so much on allusion and idiom. By listening closely to the speaker’s tone of voice, we can all identify with the mixed feelings that he has about his job – you know?

Suggested poems for comparison:

- My Last Duchess by Robert Browning

Perhaps the most famous example of a dramatic monologue in English poetry, the formally polite words of Browning’s Duke conceal his ruthlessness and deliver a carefully veiled warning to a visiting emissary.

- The Negress: Her Monologue of Dark Crepe with Edges of Light by Norman Dubie

This incredible poem will blow you away. Dubie writes in the voice of Chloe, an escaped slave penning a letter to her former mistress. The account of her journey is funny, spirited, horrifying and surprising. A brilliant example of a dramatic monologue poem.

- Rain by Hone Tuwhare

Tuwhare’s award winning poem, voted New Zealand’s favourite in a 2007 poll.

- Shirt by Robert Pinsky

Like Monologue, Pinsky’s poem reveals the working conditions of modern industry, this time in a turn-of-the-20th-century New York textiles factory.

- Quiet Work by Matthew Arnold

This Victorian poem presents an interesting question: all of nature seems to be able to reconcile work and leisure – so why can’t mankind?

- Toads by Philip Larkin

An all-time classic poem. Larkin laments that he has to work six days just so he can put his feet up for one. The brilliant thing about this poem is how Larkin compares work to a toad squatting heavily on his chest. At the end he wonders, despite all his complaints, if he would be the same man if he didn’t have to work.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Monologue at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis and would like to discover more, you might like to download our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on Speaker and Voice.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice essay questions with help and advice – including one complete essay plan for you to use.

And… discuss!

What do you think of Hone Tuwhare’s Monologue? Do you think his worker is being completely honest with us? Can you relate to his difficult situation? Why not leave a comment and start a discussion below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.