Elizabeth Smither weaves a life lesson from strands of her own hair

“Some of the best short lyrics ever produced in New Zealand”

Gregory O’Brien

Picture the scene – it’s a PE class and the teacher nominates two captains to pick teams. One by one they choose their teammates, almost always starting with the biggest and strongest. Or a teacher asks classmates to choose a partner for a graded project, and everyone tries to grab the smartest collaborator. It’s a scientific fact that when a weaker solution is added to a concentrated one, the resulting mixture is diluted. But not everything in the world follows such cold, clinical principles. In today’s poem, Elizabeth Smither asks what if, instead of putting ourselves in competition with each other, or excluding those we think don’t have the strength or smarts to contribute equally, we disregard those differences and work together for the benefit of all?

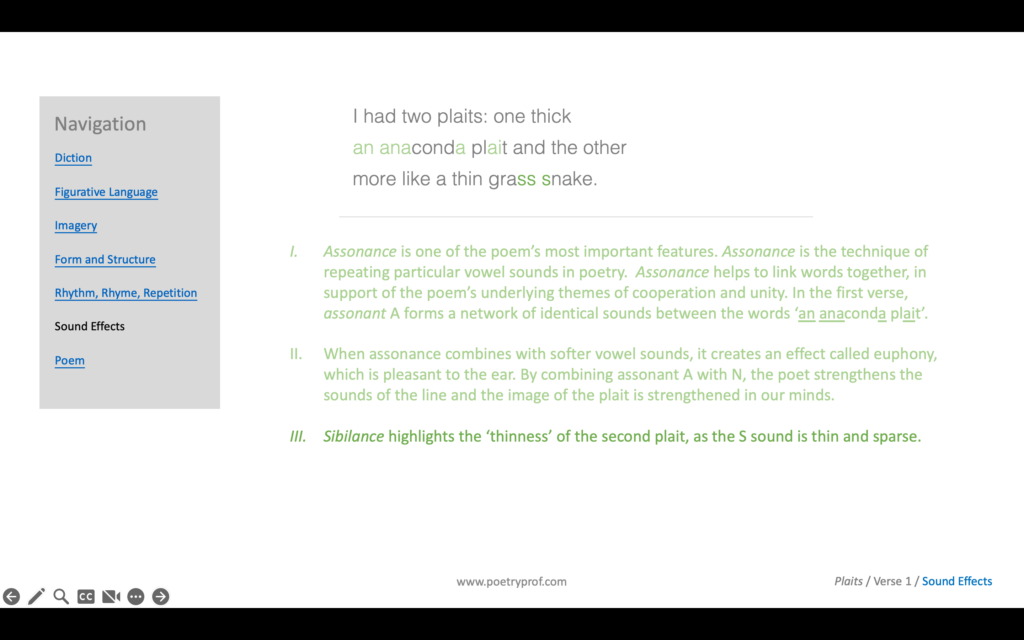

I had two plaits: one thick

an anaconda plait and the other

more like a thin grass snake.

My parting was on one side

a harvest, a rich waterfall

and a thin trickling river

but they were companionably joined

and tied with a wide ribbon

whose loops and bows were equal.

The weak and the strong

were strong together, the raised segments

of hair, a wide and thin muscle

a lesson that hung down my back

so though I could not see justice

I could feel how it was distributed.

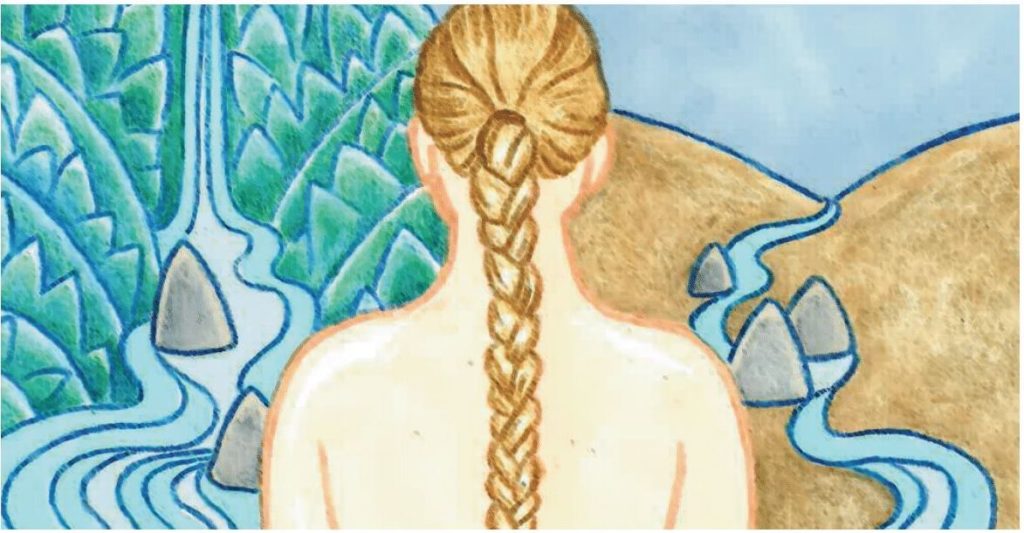

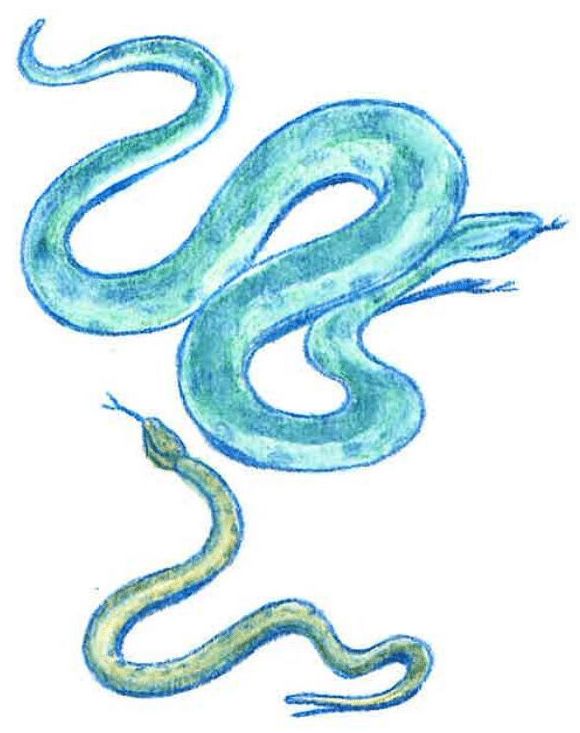

The poem rests on a deceptively simple extended metaphor prompted by a childhood memory (notice the past tense I had… that opens the poem) of the speaker braiding her hair into two plaits. She remembers how, due to the way her hair naturally parted on one side, the braids were never equal: one was thick and the other thin, a contrast established in the opening stanza and extended throughout the poem in a series of images, similes and metaphors. Her thick braid is compared to an anaconda snake, muscular and strong, while the thin braid is described as a grass snake, tiny by comparison. Later she places the image of a luxurious waterfall next to one of a thin trickling river. Each separate juxtaposition (this is the deliberate placing of two things side by side to encourage comparison) reinforces the poem’s central image: that on one side of her head dangles a thick, strong plait, while on the other side the hair hangs in a thinner pigtail.

These metaphors appear so obvious on the surface that you might be tempted to skip quickly down this poem. But pause for a moment and allow the images to coalesce more fully in your mind. Even though we humans tend to be highly visual creatures, writers craft imagery that encourages us to combine our senses and perceptions. For example, when contemplating the snake comparisons, the aspect of size readily plays into our visual appreciation and helps us easily imagine the thicker and thinner braids. But there’s a solid muscularity to the anaconda’s body that gives us an appreciation of weight too. The sinuousness of the snake is capable of conveying something of the hair’s wave, which is connected to movement, and this impression is enhanced by the rich cascade of the waterfall image. On the other side, the grass snake is slim; in addition, the way it might flick its tail suggests the bouncy movement or slight upturn of hair at the end of the plait. The diamond patterning of snakeskin suggests the crosshatch texture of plaited hair, three strands twined one across the other in turn. The one image that is not directly mirrored is harvest, which connotes the plentiful gathering of hair on the strong side as if her head is a richly grown field, again conveying something of texture as well. In terms of her poetic style, Smither often crafts images of New Zealand’s evocative landscapes, and the pastoral flavour of the images in Plaits recall Smither’s childhood natural surroundings.

This kind of deeper appreciation extends to the way Smither arranges her lines of poetry as well. She often places images side-by-side, nestling one against the other like the two plaits on her head. Juxtaposition automatically encourages contrast; bright objects seem brighter when placed next to dark ones, tall people seem even taller when standing beside shorter people, roughness feels rougher after touching something smooth… and so on. In this case, though, we should remain open to the inherent similarities between each pair of images as well. Notably, Smither doesn’t compare a strong anaconda snake to, say, a fine length of thread. She compares one snake to another, just as she compares a waterfall to a river, both bodies of water. We should be cognisant of the idea that, while one braid is thin and the other resplendent, they both grow out from the one head and their essential nature is the same. These thoughts are important if we consider the two plaits symbolically, so they stand for more than themselves. As a poem centered around a childhood memory, it has a very reflective tone and we can begin by thinking about the hair as a symbolic extension of her childhood self. Perhaps her unequal plaits represent stronger and weaker qualities of her as a person; confidence and shyness, perhaps, as one plait flaunts itself proudly. Often a beauty marker (traditionally so for many women), strands of hair may stand for beautiful and less beautiful aspects of her appearance, or even suggest traits corresponding to her ‘inner beauty’ – kindness and generosity, for example. Interpreted in this way, the speaker implies she has learned that imperfection derives from the same place as strength; each is as much a part of the totality of her being as the other, no matter the apparent strength/beauty of one and weakness/ugliness of the other. Put simply, nobody is perfect and that’s just natural.

The turning point or key moment of the poem comes when the two unequal plaits are tied up in a ribboned bow. The turning point is signalled clearly by the word but that begins the third stanza. The wide ribbon is, in many ways, just as symbolic as the hair it corrals. Pointedly described as equal, Smither leaves us in no doubt that, whatever the initial differences between left and right braid, once coupled up by the ribbon’s loops and bow, the individual gets subsumed by the whole. It’s a powerful image of collaboration or unity, or a resounding call to let one’s strengths compensate for any individual weaknesses. From the moment the two are joined, the obvious contrasts that characterised stanzas one and two disappear, and Smither introduces repetitions that accentuate the unity of the single braid. Wide is repeated between stanzas three and four, and the lines The weak and the strong were strong together employs a repetition that resolves any distinction: what was weak and strong when separate becomes strong when working together. Technically, this type of repetition is called diacope, as the repeated word strong is interceded by the word were. Diacope gives these lines a noticeable rhythm (read the weak and the strong were strong together out loud and feel how your voice instinctively accents weak… strong… strong… together) that conveys the pleasure of the moment when two become one. The final line of stanza four gives us wide and thin in something like an oxymoron, describing the single length of braided hair as a wide and thin muscle. This line creates a tactile sense of the hair’s new shape, and an appreciation of tensile strength – not necessarily brute or hard strength, but a lean, supple, flexible strength that one can depend on for support.

At the same time, the use of the phrase companionably joined requires us to rethink the poem’s symbolism. Referring to a state of friendship between two people, the word ‘companionably’ personifies the two strands of hair, as if they are two people overcoming differences to form a partnership. Their differences may have been physical, or they may have different personalities or characteristics. Nevertheless, once joined and tied together, these differences become moot. Given the close and intimate action of hair-braiding, and the way we use the word tied in the phrase ‘family ties’, we might relate this coming together to a kind of symbolic marriage. As two very different people might complement each other to mutual benefit, so the two plaits of hair become strong together. The fourth stanza makes this point firmly through the use of the word raised: rather than the weaker half dragging the stronger half down, the opposite becomes true when the raised segments of hair are both elevated.

Once again, the simplicity of the poem’s central metaphor disguises the complexity of Smither’s craft. As if she is in truth braiding strands of hair in a complex weave, Smither weaves poetic effects to reinforce her themes of cooperation and unity. Aurally, there are plenty of subtle patterns that link words together, especially through assonance: a light I sound runs through thin trickling river (at this point in the poem the ‘thinness’ of the single braid is expressed through the thin sound too); an anaconda plait is a woven a lattice of assonant A sounds in just a few words. Although her poem doesn’t rhyme, as the ribbon brings together the two different plaits of hair, Smither adorns this line with a prominent internal rhyme: tied/wide. The transformation brought about by the tying together of two plaits is further expressed through assonance (whose loops and bows); long, wide O sounds that transform the sonic texture of the poem into something richer. Other half rhymes link words together through faint echoing: ribbon/strong and lesson/hung are two moments where this sense of blending is audible. On a visual level, the poem’s spatial form (otherwise called its shape) mimics the technique used to braid hair in strands of three. The poem is written in tercets (the technical name for verse of three lines each) and while Smither is a free verse poet (she doesn’t set her lines to a regular rhythm or meter), nevertheless each line has a similar length and resembles individual strands of hair. Visually, each stanza is a ‘plait’ woven of three lines.

In the final stanza, Smither delivers the lesson she learned as a child in a didactic way, pretty much spelling out the symbolism of the combined plait. As we suspected all along, the twin plaited strands stand for more than themselves: she says her hair became a lesson that hung down my back, a line in which the word hung transmits its own kind of weight: it’s a deep, sonorous word that cuts across the lightness of the poem and reverberates with the force of revelation. In the final verse, she equates the weight of her hair to the weight of justice. Smither’s lesson, one that she learned as a child and now passes to us, is that justice only truly exists when the weak and the strong work together for the benefit of all. The equally braided and fairly distributed queue of hair now hangs neatly down the center of her back, representing a situation where strong and weak collaborate together, and where no one is excluded. Remembering that Smither is a New Zealand poet, she may be reflecting on New Zealand’s own history of injustice between white settlers and the Maori people they displaced. However, the poem doesn’t restrict itself to this viewpoint. Both the central symbol of a schoolgirl plait, and the natural images she crafts (snakes, rivers, waterfalls) along the way, suggest her vision is more universal – a vision of a whole world in which competition is replaced by collaboration, and people share what they can in working towards a common good.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Sleeping on a Waterbed by Elizabeth Smither

Proving that anything can be the subject of poetry, Smither elevates the simple act of lying on a waterbed to a moment of discovery and revelation, as she shifts and squirms, and the sounds of the sea wash over her.

- For Heidi With Blue Hair by Fleur Adcock

Another poem in which hair takes centre stage. When a girl is sent home by a strict headmaster for dying hr hair in a different colour, her friends rally round in a show of solidarity.

- Cutting Hair by Minnie Bruce Pratt

This beautiful prose-poem is a tribute to an elderly lady who cut hair for a living all her life. Maybe taking her services for granted, this work goes largely unnoticed. But read to the end, and spend a few moments appreciating the beauty of the closing image; hair lying strewn around the speaker’s feet like newly scythed hay.

- Sonnet 68 by William Shakespeare

Even one of history’s undisputed master sonneteers was not above taking hair as his inspiration – and Shakespeare was famously bald! (Actually, this sonnet is mostly about wigs, but I hope you’ll enjoy it anyway).

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Plaits at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. These bundles normally cost £2.50, but you can have this one for free. Please check out all the resources inside, which are useful in all kinds of study situations: whether encountering the poem for the first time; deepening your understanding of the poet’s craft; revising; or for practicing the way you write analytically. This bundle includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how assonance works in the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Elizabeth Smither’s poem? How do you think the plait resembles true justice? What images does her simple language conjure for you? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.