Thomas Love Peacock exposes the unfairness of religious moralism towards the poor.

“He certainly deserves to be better known.”

Robert McCrum, writing about Peacock’s satires.

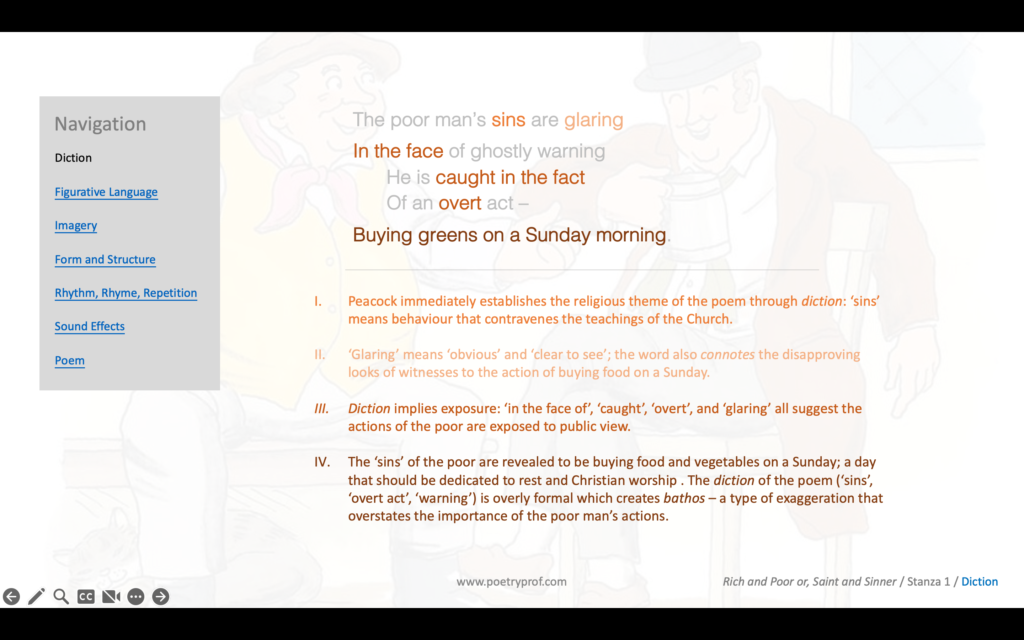

Nineteenth century Britain was a strongly religious society. Most people would describe themselves as Christian, and their beliefs influenced how they behaved. Leading a good Christian life meant being obedient, charitable, honest, going to church and doing good deeds. Oh, and not doing any work on a Sunday! Originating in Judaism (where the Sabbath day is a Saturday) Jews were obliged to sanctify the Sabbath at home by engaging in worship and study. In the year 321, having converted to Christianity, the Holy Roman Emperor Constantine issued a decree that Sunday would, after the Jewish manner, be a day dedicated to worship and the observation of Christian rest. The ban against work is not perfectly defined, but includes activities such as baking, carrying burdens, writing, sewing and weaving, gathering wood, trading, building and so on. Observing this code of conduct was seen as a religious and social duty for Victorians – at least, for those who could afford to do so. This is where Thomas Peacock Love comes in. Famous as a satirical novelist, Rich and Poor or, Saint and Sinner is an example of Peacock applying his satirical skills to poetry as well:

The poor man’s sins are glaring;

In the face of ghostly warning

He is caught in the fact

Of an overt act –

Buying greens on a Sunday morning.

The rich man’s sins are hidden

In the pomp of wealth and station;

And escape the sight

Of the children of light,

Who are wise in their generation.

The rich man has a kitchen,

And cooks to dress his dinner;

The poor who would roast

To the baker’s must post,

And thus becomes a sinner.

The rich man has a cellar,

And a ready butler by him;

The poor must steer

For his pint of beer

Where the saint can’t choose but spy him.

The rich man’s painted windows

Hide the concerts of the quality;

The poor can but share

A crack’d fiddle in the air,

Which offends all sound morality.

The rich man is invisible

In the crowd of his gay society;

But the poor man’s delight

Is a sore in the sight,

And a stench in the nose of propriety.

The rich man has a carriage

Where no rude eye can flout him;

The poor man’s bane

Is a third-class train,

With the daylight all about him.

The rich man goes out yachting

Where sanctity can’t pursue him;

The poor goes afloat

In a fourpenny boat,

Where the bishops groan to view him.

Wealth was inseparably intertwined with morality in the Victorian mindset. Children’s books were full of morality tales in which respectable, well-behaved children were rewarded – and poor, naughty children were punished or met some kind of grisly demise! The very title of today’s poem, Rich and Poor or, Saint and Sinner conflates money and morals through parallelism, rich and poor on one side, saint and sinner on the other, as if one state of being is a straightforward substitute for the other. The Victorian tendency to judge morality through the prism of social class is further conveyed through the frequent metaphorical renaming of rich and poor people. Here, those of high station are given names such as quality, saints, gay society, and propriety, suggesting the upper-classes are upstanding and untouchable paragons of virtue. On the other hand, the poor are labelled either sinners or rude, names that suggest an inherent offensiveness and immorality. But don’t be fooled – in this regard, the poem fairly drips with irony and you have to be sensitive to words that suggest the opposite of their denoted meaning. When he renames the rich quality, for example, Peacock’s not simply falling back on stereotypes; he’s pointedly calling out the tendency to elevate those with money and denigrate those without. Those who like to pronounce judgment upon others are introduced as the children of light, a name that alludes to a passage from the Bible reading: ‘And the lord commended the unjust steward, because he had done wisely: for the children of this world are in their generation wiser than the children of light.’ Peacock usurps the name to describe any person, but especially religious authority figures (bishops are explicitly mentioned in stanza eight) and everyday street-side moralisers quick to throw the accusation of sinner at the poor while turning a blind eye to the misdemeanours of the rich. When he calls them wise in their generation, what he really means is ‘narrow-minded’ and ‘blinkered’ in their unsympathetic attitudes.

Peacock mimics their style of overblown castigation through a satirical technique known as bathos; akin to exaggeration, bathos is created when trivial subject matter is treated with the utmost importance. The necessary purchase of food, buying greens on a Sunday morning, should hardly be accounted a criminal misdemeanour; yet Peacock describes buying food to eat as an overt act akin to a flagrant crime or sinful disregard of upright Christian behaviour. Peacock slowly builds up to the big reveal of what the poor man’s sins actually are, waiting until the final line of verse one to present the heinous act in all its glory; caesura (the preceding hyphen) creates a dramatic or pregnant pause before the last line lands with the force of a judge’s gavel. He peppers the rest of his poem with bathetic language too: sore in the sight, offends all sound morality, and stench in the nose mix up sensory impressions to convey the visceral reaction of morally righteous citizens shocked to the core at the weekly depths of depravity to which the poor descend. To a sympathetic reader, soon enough it feels like the poor man can hardly twitch a finger without being subject to some kind of pious judgment on the part of wider society. You may have seen a historical drama set in Victorian times where a rich person is forced to walk through a poor neighbourhood and does so gingerly, reluctantly, clutching a perfumed handkerchief over nose and mouth, an idea hinted at by diction such as sore and stench, as if poverty is a kind of pollution or sickness. By the time the bishops groan in the final line, Peacock’s irony is unmistakeable, their reaction audibly evoking the martyred exhaustion of having to deal with persistent rule-breaking – even if it’s just a poor man crossing the river to the veg-market on the other side. There’s a suggestion that, from the morally upright point of view, the poor are acting wilfully and might even be quite gleeful about all this. In particular the phrase can’t choose but spy him evokes the uptight disgust of an unbending Christian having his nose rubbed in such flagrant disregard for the rules. Couched in an overblown, sanctimonious diction (such as sanctity in the final stanza) Peacock’s tone subtly scorns the hypocrisy of those who would point the finger of blame at a poor man, while ignoring the moral failures of the rich.

In fact, Peacock’s poem undermines the idea that good breeding and respectability separate wealthy Victorians from the lawless poor. If a person is judged by actions rather than how much money they happen to have, the rich and poor in the poem don’t seem to be that different after all. Sunday is meant to be a day of rest and religious worship for all; nevertheless members of opposite social classes both contravene the ban on work, whether by cooking a meal, travelling, or revelling in music and drink instead of going to church. The poem repeatedly juxtaposes the actions of the rich and poor, placing them side-by-side so it’s impossible to refute the similarities between them. For example, in the third verse, both rich and poor prepare dinner in contravention of the prohibition against cooking. However, while the poor who must roast to the baker’s must post (rare was the poor house that had a stove or kitchen; lacking the ability to cook their own meals, poor families would club together for a tradesman to help, thus exposing their actions to public criticism) the rich would have in-house cooks to prepare (dress) the Sunday roast for them. Throughout the poem this pattern is reiterated over again (reiteration is the repetition of the same idea in different words). Through juxtaposition, the actions of the rich are always paralleled by the poor, the only measurable difference (apart from quality and comfort) being the idea of ‘exposure’: where the poor man drinks in a public house the rich man has a private cellar; the poor man revels in the street while the rich man invites all his friends around to the mansion for exclusive private concerts; the rich man travels in a horse-drawn carriage, curtains down so no rude eye can flout him (you can read rude to mean ‘intrusive’ and should understand flout by its archaic definition, ‘to mock or scoff at someone’), while the poor man travels on the train in third-class, squeezed onto a packed bench alongside plenty of other people; the rich man goes yachting far out to sea, away from prying eyes, whereas all the poor man can afford is a fourpenny boat suitable for river-boating, so remains in plain view to any who walk along the towpath. In verse two Peacock boldly states: the rich man’s sins are hidden. This line almost word-for-word parallels the first line of the poem (the poor man’s sins are glaring) to emphasise his belief that the only difference between rich and poor is that those with means and money escape censure whereas those without are caught in the act.

That’s mainly because those fortunate enough to have the money shroud themselves in secrecy. Able to afford high walls, thick curtains, and even to buy the silence of accomplices (cooks, a ready butler, horsemen for his elegant carriage would all have been in the rich man’s employ and unlikely to bite the hand that feeds them) they need not fear the criticism of their contemporaries. Peacock frequently uses words from the lexical field of ‘concealment’ that also connotes an element of deceit: hidden, escape the sight, hide, and invisible. Painted curtains (luxuriously dyed fabrics, shutters, blinds, shades, screens, drapes – anything that can cover a window) become symbolic barriers keeping insects, street smells, the heat of the sun, and prying eyes out. Despite the widespread belief in their own upstanding morality, the diction Peacock chooses to use implies furtiveness, as if the rich deliberately hide sinful behaviour from scrutiny. He further develops a pattern of visual imagery that either conceals the actions of the rich or highlights the behaviour of the poor. One verse might be cast in a shadowy, secretive darkness while the next is bathed in bright light. The very first line contains the word glaring, implying a revealing light as well as being a word that connotes an angry or disapproving expression. The poor are always exposed, their lives lived in the open or under the revealing glare of an unforgiving light: in the face of, overt, in the air, in the sight, daylight all about him, and view are all words and phrases that expose the actions of the poor to public view. Even sound effects contribute to the idea of exposure. There are a few examples of alliteration scattered here and there (glaring alliterates with ghostly in verse one; poor with pint in verse four; sore, stench and sight in verse six – I’m sure you can find a couple more examples elsewhere) which very effectively call the reader’s attention so certain words and actions stand out like the proverbial sore thumb. By necessity living more ‘open’ and public lives, the poor are more exposed than their wealthier counterparts to public scrutiny, suspicion and disapproval. By the time we get to the end of the poem, Peacock has left us in no doubt that, while rich and poor may live side-by-side, in practice they inhabit two very different worlds.

The tension between rich and poor is further echoed in the poem’s form, which you may agree is quite unusual and creates some interesting accentuating effects. Peacock writes in rhyming stanzas of five lines each, that follow a metered rhythm making the poem seem more sing-song than its subject matter might deserve. I may be mistaken, but each verse sounds just like a limerick, which is a type of bawdy doggerel more suited to smutty rhymes and tawdry subjects than a study of social inequality! Whether the form is a true limerick or simply cleaves close to this form, the first, second and fifth lines contain three stressed beats and the third and fourth, sandwiched uncomfortably in the middle, contain only two. From verse three to verse eight, the contrast between rich and poor is evident in the way rich actions are described in the longer, more leisurely lines, while the poor live their lives in restricted circumstances on the shorter middle two lines. More subtly, you may have noticed that the first, second and fifth lines always end on an unstressed syllable; lines that end on this weaker note are written in falling rhythm. By contrast, the third and fourth lines end on a downbeat, or stressed syllable, forming rising rhythms. Although you may not be aware of this subtle contrast, your mind’s ear will catch the interplay of falling and rising rhythms that echoes the central conflict between rich and poor. Contrasts like this are made even starker by the poem’s rhyme scheme which always matches the first, second and fifth lines together, while lines three and four rhyme with each other as well. Furthermore, Peacock uses spatial form (the simple presentation of lines on the page) to accentuate the rich/poor contrast by indenting or off-setting the third and fourth lines, although this was also a printing convention of the time, so you shouldn’t over-egg the pudding in regard to the poem’s shape.

The nineteenth century saw the formation of London’s first police force whose job it was to take care of crime in poor communities. Victorians believed in harsh punishments and these new ‘bobbies’ were disliked by the poor who believed they were being spied upon; the poem contains the words spy and pursue to imply the purposeful targeting of poor communities. Their suspicions were not unfounded; poor people could find themselves sent to prison for relatively minor crimes. In reality, problems associated with drink, drugs, thievery, prostitution, and so on disproportionately affected poor communities because of dire social conditions. But that didn’t stop wealthy Christian moralists believing that poor people were inherently wicked and had to be shown the error of their ways. Sadly, in our modern societies, wealth inequality is worse than ever before. And, despite our supposedly enlightened views compared to our Victorian forebears, people living in poverty are still sometimes tarred with the brush of immorality; labelled ‘scroungers’, ‘lazy’, ‘work-shy’, and so on, they are subject to the same kinds of prejudice Peacock was exposing over 200 years ago. Just as those weary bishops would rather the poor stayed out of sight and out of mind, by their simple (and normally harmless) presence on public streets, poor and homeless people might call down the ire of the more fortunate. If reading his poem today achieves anything, it should be to remind us to check our own reactions next time we’re confronted by poverty – not having enough money isn’t normally a personal choice or moral failing, but a failing of society and politics instead.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- I Dug, Beneath the Cypress Shade by Thomas Love Peacock

A master of lyric verse, this short and not-so-sweet poem also demonstrates Peacock’s prowess with rhythm and rhyme. It describes a lover’s reaction after a disappointing failed romance in ways both poignant and painful.

- Song to the Men of England by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Peacock was a family friend of Percy Shelley and something of a pupil to the great poet. They shared similar ideals – yet Shelley was not immune to Peacock’s satire (although he very much enjoyed being made the butt of the joke). In this poem, Shelley deals with similar themes of inequality and social injustice – although he gets much angrier about it!

- Song of the Shirt by Thomas Hood

Written as the speaker sits listening to a seamstress work, this Victorian poem, like Peacock’s, is interested in exposing the lamentable situation of the poor, and the ways they are treated and viewed by wider society. Another example of a writer expressing deep empathy for other people and the situations they find themselves struggling in.

- Let America Be America Again by Langston Hughes

Born at the turn of the twentieth century, across the pond, Harlem poet Langston Hughes wrote about social and racial equality in his time. This is one of his most famous poems, written in the voice of the oppressed.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Rich and Poor or, Saint and Sinner at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how metaphors are used in the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Thomas Peacock’s poem? What are your thoughts about the ways people tend to judge others? Do you think this poem might still be relevant today? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Hi, the line “And a stench in the nose of propriety” should be “And a stench in the nose of piety”.

Source: Songs of Ourselves 2

You’ve done a great job of analysing the poem. It has given me a vivid idea of its background and its satirical content. Would love to keep on getting such insightful analyses from you. Thanks