Norman Nicholson warns us not to wish our lives away.

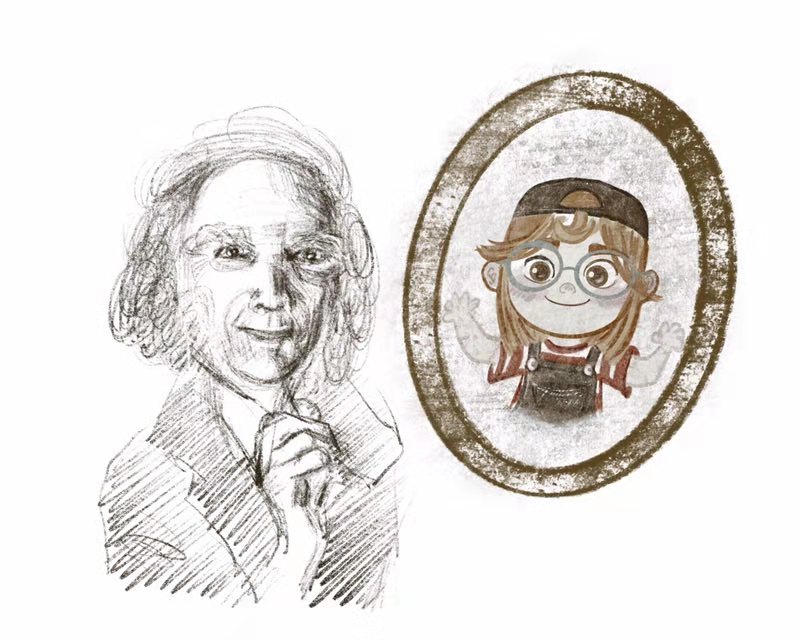

“A unique, gentle spirit with a quirky sense of humour.”

Kathleen Jones (author of The Whispering Poet, Nicholson’s biography)

Do you ever do that thing, when someone asks how old you are, reply, “Coming up twenty-five,” “Nearly twelve,” “Almost 40,” “I’m turning sixty this year,” or however old you happen to be next birthday? I certainly have: if I’m honest, I must have spent the entire decade saying to people, “I can’t believe I’m nearly…” Today’s poem begins with a little boy doing precisely this – pointedly correcting somebody with, “I’m not four, I’m rising five.”

‘I’m rising five’, he said,

‘Not four’, and little coils of hair unclicked themselves upon his head.

His spectacles, brimful of eyes to stare

At me and the meadow, reflected cones of light

Above his toffee-buckled cheeks. He’d been alive

Fifty-six months or perhaps a week more:

Not four,

But rising five.

[blur]

Around him in the field the cells of spring

Bubbled and doubled: buds unbuttoned; shoot

And stem shook out the creases from their frills,

And every tree was swilled with green.

It was the season after blossoming,

Before the forming of the fruit:

not May,

But rising June.

[/blur]

Please click here to read the full version of Rising Five.

[blur]

And in the sky

The dust dissected tangential light:

not day,

But rising night;

not now,

But rising soon.

[/blur]

The new buds push the old leaves from the bough.

We drop our youth behind us like a boy

Throwing away his toffee-wrappers. We never see the flower,

But only the fruit in the flower; never the fruit,

But only the rot in the fruit. We look for the marriage bed

In the baby’s cradle, we look for the grave in the bed;

not living,

But rising dead.

Norman Nicholson hails from the Lake District in Cumbria in the northeast of England. Much of his poetry is rooted in the local landscapes and inspired by local voices, people and customs. So entwined was he with this part of the world that, even to this day, there’s a Norman Nicholson Society and a Norman Nicholson Festival (yes, really) in and around Millom, the town where he was born, lived, married and died. Rising… is a local turn of phrase that can be read as ‘almost,’ ‘coming-up’ or ‘nearly,’ – the boy is enthusiastically looking forward to growing older, growing up. He can’t wait to rush ahead to the next phase of his life. Look at the eager way he stares at me and the meadow through reflected cones of light – as if his eyes are popping out of his head! From this small encounter with a little boy, Nicholson’s poem uncoils like a compressed spring, whizzing through the boy’s life as he grows up before our eyes. Instead of being charmed by the little boy’s energy and enthusiasm, Nicholson is worried. He looks to the future so excitedly that we might wonder if he ever takes time to appreciate the things around him in the present. The end of the poem demonstrates the inevitable consequence of hurrying through life with this kind of attitude.

The character of the ‘Little Boy Who Zooms’ is introduced in four economical strokes of Norman Nicholson’s pen. His first words are the first lines of the poem, I’m rising five… not four; we can straight off the bat hear him wishing he was just that little bit older than he really is, presumably so he can rush off and do all the things little boys like to do, like running around in the meadow. Startlingly, we see an image of hair growing out of his head – he’s getting taller and older right in front of our eyes! The diction little coils… unclicked, suggests the quick unwinding of a spring or the ‘tick-ticking’ of a clock (an impression fortified by alliteration: coils…unclicked). If you’ve ever squeezed down on a spring, then let it go flying, you’ll know how apt this image is for conveying the pent-up energy of a young boy who just wants to go-go-go. Thirdly, we get another image of his eyes seen through thick glasses: his spectacles, brimful of eyes to stare… reflected cones of light. The distorting effect of looking through a lens makes his eyes seem huge, as if he can’t wait to see all the world has to offer, nicely illustrating his over-eager character.

The last of the four is probably the simplest to decode, but the most cleverly used. We are given a descriptive metaphor, toffee-buckled cheeks. The association of the boy with eating sweets emphasises his youth… but we have to wait until the end of the poem for the symbolism of the toffee-wrapper to pay off. When the older version of the boy (Norman Nicholson himself, perhaps?) looks back over his life, he says we drop our youth behind us, like… toffee-wrappers: the image tells me he feels he was too eager to move on in life, disregarded his own youth, and maybe wasted opportunities that have now gone. Phew! Take a quick look back over stanza 1 to appreciate how Nicholson sketched all this in just a few short lines – appropriately enough wasting no time at all.

Once the boy gets going he moves incredibly quickly and, if you’re not careful, it’s easy to get lost in the speed of the poem. Just looking at all the various references to time passing can make your head spin. Nicholson doesn’t stick to one metaphor– say, using spring to represent youth and autumn or winter to represent old age. Instead he skips from one ‘metaphorical tracking system’ to another. On first reading it might be a bit tricky to follow, but I quite like the way he jumps from one figure of speech to another; it really suits the character of the boy, rushing ahead, not stopping for a moment, just picking up and running with whatever idea happens to take his fancy. That’s not to say the metaphors are random – the boy might be careless, but the writer is not. For the first three stanzas at least, they are presented chronologically, and approximate different stages of a person’s life.

The ‘tracking system’ begins by using numbers (which made me consider how even our numbering system is a metaphor for the passage of time). The boy replies to an unseen question, I’m rising five… not four. Later in the stanza a pedantically exact fifty-six months, perhaps a week more tells us exactly how old he is almost to the day. Expressing his age in months instead of years is nice touch, making the boy seem much older than he really is; he’s rushing ahead so fast that in no time he’ll be middle-aged. Then, in stanza two, the ‘lifetime tracking system’ switches to seasons: spring turns to summer (every tree was swilled with green) in the blink of an eye. May and June mark the middle part of a life. The short stanza 3 sees a further adjustment to the ‘tracking metaphors’: the sun sets and night falls (and in the sky the dust dissects tangential light). At this point, youthful optimism vanishes and is replaced by something more pessimistic: dust and night can both be associated with old age and even death. In the final stanza Nicholson gives us two parallel metaphors: a flower that bears fruit, then rots; then three different beds we use at different stages of life: the cradle, a marriage bed and a grave.

Reading the second stanza feels like watching one of those brilliant nature documentaries that speeds up a time-lapse film of plants growing. In just a few seconds you can watch seeds sprout, stems shoot up, bud, bloom, flower, fruit, trees shed leaves and wilt again. The first line gives us an ultra-close up of cells that bubbled and doubled, as if we are looking through a microscope watching mitochondrial life begin. Before our eyes buds unbuttoned, blooming into lushly leaved trees. This part of the poem is euphoric, as if the boy is revelling in the prime of his life; a perfect time expressed as the season after blossoming / Before the forming of the fruit. Even this line – the most vibrant time to be alive – contains a sense of anticipation, as if the boy is waiting impatiently for the fruit to form rather than enjoying the season’s other, obvious pleasures. By now his life is at a turning point, sensed in the delicate juxtaposition of before and after. Surely this euphoria can’t last…

Before we move on too quickly, let’s pause and take a closer look at stanza two (Nicholson would agree with this sentiment, I reckon) to discover how patterns of sounds compliment that time-lapse film:

Around him in the field the cells of spring

Bubbled and doubled: buds unbuttoned; shoot

And stem shook out the creases from their frills,

And every tree was swilled with green.

Because time is passing so quickly, sound helps accelerate the pace of the poetry, leaving the reader a little breathless in places. Alliteration skips through the verse, running from word to word likes the boy rushing through his life. Begin by finding the C sounds in the first line (cells of spring); then jump straight into line 2, which whizzes past in a blur of D and B sounds. T and SH poke their heads through the leaves in lines 2 and 3: unbuttoned, shoot, stem, shook. Then, like a relay runner passing a baton, CK and F sounds take over: shook/creases, from/frills. Finally, liquid sounds (R, W and L) bring it home: from, frills, every tree was swilled with green. Liquid alliteration is good at creating pace and flow; just what Nicholson wants us to feel here. Not content to rely on one device, he throws assonance into the mix: look how the short U runs into the longer OO sound in line 2: bubbled and doubled: buds unbuttoned; shoot. I’m sure you noticed the long EE in tree and green– you can also hear it in creases and every. To top it all off you can find no less than four internal rhymes: bubbled and doubled; shoot and shook; frills and swilled; tree and green (paired words in which either the consonant or vowel rhyme are half-rhymes). Sounds repeat, echo and overlap, running from word to word; all contribute to the sensation of time rushing past in the blink of an eye.

No wonder the poem takes a darker turn once May slips into June and the halfway point of a life is reached. Stanza 3 is brief as a sunset;

And in the sky

The dust dissected tangential light:

not day,

But rising night;

not now,

But rising soon.

We can see those sound patterns again, D and S, N and T skipping through the second line especially. But more important here is the imagery. Day turning to night is symbolic of time reaching its end, a life almost over. The way it is expressed – dissected, tangential– is odd but apt, almost mathematical. We should take these words one at a time. Dissect means ‘to cut,’ like sunlight can sometimes be seen cutting through clouds, or trees, or even a window. Have you ever seen sunlight shining at an angle like this, catching and illuminating all the miniscule motes suspended in the air? It’s a captivating moment – made all the more precious by the fact that it’s gone so quickly. Tangential refers to a line that intersects with a curve at only one point (strengthening the sunset image as the sun’s rays intersect with our atmosphere) but it also means a digression or an indirect course of action. It’s exactly the sort of thing the boy wouldn’t do; take a slow, meandering route somewhere or appreciate something for its own sake. This is Nicholson’s point – to catch these moments of unexpected beauty in life we have to pause occasionally, sit in a comfy chair and let the world present us its marvels. After all, a moment ago, the trees were covered in green leaves. The juxtapositions of green / dust, day / night, now / soon really drive this point home: if you don’t appreciate what you have now, soon it will be gone.

That tiny third stanza can be seen as the hinge around which the poem turns. After this moment, things change rapidly. Take the perspective of the poem. To begin with Nicholson was standing opposite the boy, observing him and talking with him; he used the personal pronouns he and me. Suddenly, he aligns himself with the boy by switching to the word we. Poets are normally a little reluctant to use we (it’s called using the public voice) as it means speaking for a group of people, not just oneself; but Nicholson obviously feels the tendency to rush through life is so universal that he can speak for himself, the boy… and maybe even the reader here too.

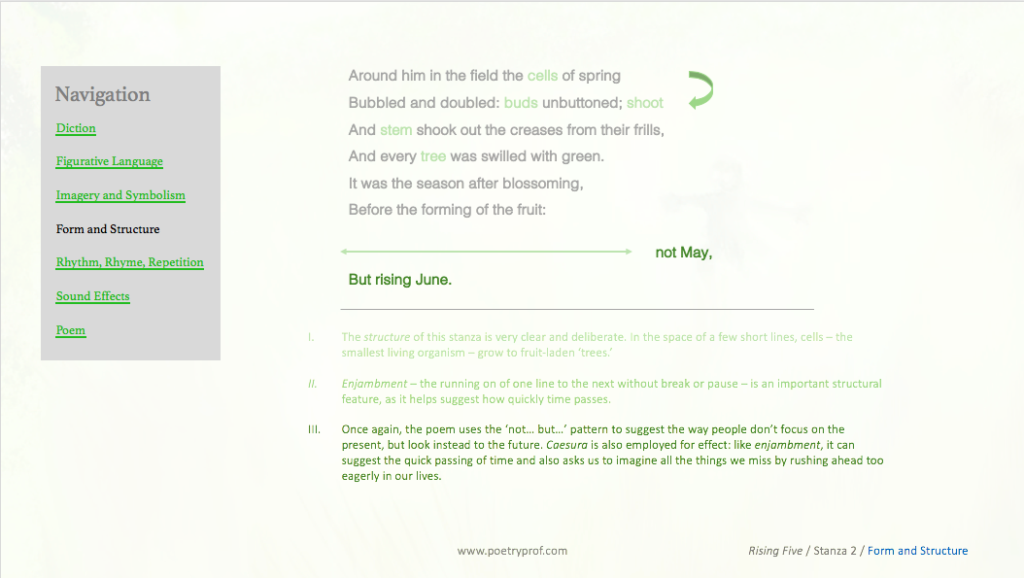

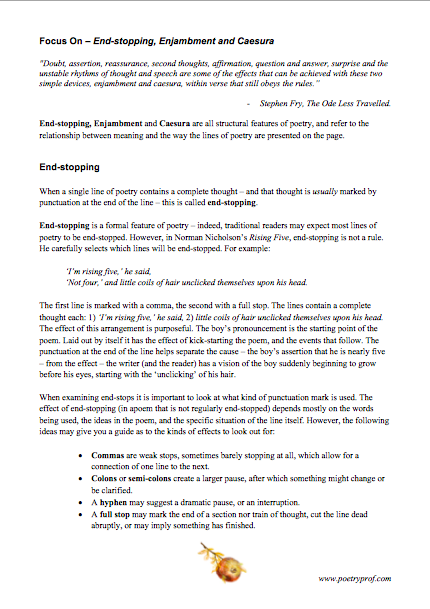

Nicholson is a fairly old-school, formalist poet. Not surprisingly in Rising Five, formal elements combine to suggest the inevitable passing of time, and the regret we will feel should we rush too quickly through our days. Let’s take a look at the repeated, not… but…structure that constitutes the poem’s refrain. Nicholson combines negation with juxtaposition to emphasise things we leave in the past when we look too much to the future. These negations become more and more precious, and what is to come less and less appealing: not four, but five; not may, but June; not day, but night; not now, but soon; finally, and ominously, not living, but dead. The refrain’s two short lines are always arranged in an offset way, using blank space to create caesura (a break, pause or gap in the middle of a line of poetry) – are your eyes eager to skip over these spaces? If the answer’s ‘yes,’ well – you’ve just fallen into Nicholson’s trap; reading ahead too fast to find out what comes next. Skipping ahead in time by leaving out parts of the story is a narrative technique called ellipsis; Nicholson puts it to good use here, using caesura to create ellipsis, a gap into which has fallen all the things you might be too busy to pay attention to. Enjambment– the way one line continues without break or pause into the next – helps the poetry slip and slide quickly down the page. Read the lines aloud and, more or less from start to end, you can hear the ceaseless tick-tock, tick-tock of iambic pentameter, metronomically counting down life’s clock from cradle to grave. Here’s the first stanza again, this time with accents marked on the beats:

‘I’m ris/ ing fīve,’/ he sāid,/

‘Not fōur,’/ and lītt/ le cōils/ of hāir/ unclīcked/ themsēlves/ upōn/ his hēad./

His spēc/ taclēs,/ brimfūl/ of eȳes/ to stāre/

At mē/ and thē/ meadōw,/ reflēct/ ed cōnes/ of līght/

And these lines from the refrain:

not dāy,/

But rīs/ ing nīght;/

not nōw,/

But rīs/ ing sōon./

The inference is clear: time moves at its own speed and in only one direction; relentlessly, inexorably forward. There’s no need to rush ahead so eagerly into the future – it will come when it comes, whatever you may do.

Nicholson leaves us in no doubt that his speaker (who may be a version of the poet himself) regrets the way he careened through life. I think he is desperate to cry out to that young boy – a mirror of himself – “slow down!” There’s a touch of bitterness about the way he imagines the new buds push the old leaves from the bough, an image that conveys the pushiness of young people, keen to put themselves forward, even if that means trampling over those in front. At the end of the poem, all the lovely images (reflected cones of light, coils of hair unclicked, swilled with green, blossoming) disappear, dropped in the past like that symbolic toffee-wrapper. Instead, in quick succession we get rot, grave and dead. The juxtaposition of these words with flower, cradle and living is marked: Nicholson emphasises all the beautiful things in life are behind him – rot, grave and dead are all that’s left to come.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Wall by Norman Nicholson

This poem demonstrates both his mastery of form (most words in the poem are one syllable each, like single stones in an ancient dry-stone wall) and his love for the evocative Cumbrian landscape.

- Warning by Jenny Joseph

You could read this as the opposite of Nicholson’s poem, in that Joseph positively looks forward to being old and promises to behave in the most outrageous way once she’s free of life’s responsibilities.

- November by Simon Armitage

The title of this poem refers not only to the time at the end of the year, but also the time at the end of one’s life. As the speaker takes his elderly relative to a hospice, the horror of ageing and the fear of death and dying dawns on him and his friend, John.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Rising Five at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on how end-stopping, enjambment and caesura are used by Norman Nicholson in his poem.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What did you think of our breakdown of Rising Five? Do you feel time slipping away as you read the poem? Do you agree that the meeting with the young boy represents the poet looking back with regret on the way he lived his own life? Leave your feedback, suggestions, questions or thoughts in the comments section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

this is just amazing! you helped me a lot in my igcse’s! your poem analysis are not only unique and different from others, you go so in-depth into the structure, rhymes and rhythm which are all really useful in the exam. You made my life so much easier, thank you for this and have a great day!

Hi,

It’s very nice to hear the blog is so helpful – best of luck in your studies.

So what is the tone and mood of this poem?

Hi Tracy,

This is one of those poems where the mood (atmosphere) changes. To begin with the poem is carefree, revelling in the joys of youth – look how energetic and enthusiastic the boy is. The atmosphere of the poem is positive, hopeful and even euphoric, especially when all around ‘the trees are swilled with green.’ For me, the turning point is ‘dusk dissects tangential light.’ After this the mood becomes darker, much more pessimistic. Words like ‘grave’, ‘rot’ ‘dead’ take over from words like ‘green’, ‘bubbled’ and ‘buds’.

I would say the tone of the whole poem is cautionary – the speaker is warning us about what happens if we rush through life always looking to the future. You might like to look at individual lines too. When the speaker says, ‘the new leaves push the old leaves from the bough’ I can hear a touch of anger in his voice. If you think the boy and the speaker are one and the same, you might also describe the tone as self-recriminating – read the line ‘we drop our youth behind us… like toffee wrappers’ as if he’s speaking to himself, wishing he hadn’t been so hasty when he was young.

Tone is one of the most challenging aspects of poetry. Try reading certain lines out loud, thinking, ‘what is the attitude of the speaker towards his subject matter’? It can change from line to line, or verse to verse. Atmosphere / mood is how you feel when you read the lines – the two are not always the same.

Hello

By using PEE (Point, explantion,example)

any 4 different ways the speaker shows impatience

Hello, I’m not sure if your comment is a question or a statement.

I would argue the speaker does not show impatience – I think he’s cautioning us against rushing through life impatiently. He meets a boy who shows impatience (it’s possible the boy is himself from the past…). If you are looking for four ways the boy shows or represents impatience, you might like to think about: the way he looks at the world (‘spectacles brimful of eyes to stare’); the way he seems to grow up so quickly before our eyes (‘coils of hair unclicked upon his head’); the way he ‘drops his toffee-wrappers’ (an action symbolising carelessness) and perhaps the line ‘the new buds push the old leaves from the bough’, which can be understood in terms of the impatience of youth.

I hope that helps. Best of luck in your studies.

Dear Poetry Prof,

I hope this email finds you well. Could you please make an essay on ‘Rising Five’?

Hi Simos,

Thanks for your message. You can find a Rising Five blog on the site. You can browse or use the search function at the top of the page.

Hope it’s helpful.