Who is the mysterious Lucy in this simple elegy by William Wordsworth?

“Think of 1798 as poetry’s pun moment… the high-falutin’ poetic diction of the 1800s was renounced; plain speech took its place, and nothing was ever the same again.”

Ncholas Lezard, Literary Critic

After I first read She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways I was left with one burning question – who was Lucy? Her enigmatic figure featured in five poems by William Wordsworth, one of which is today’s poem (the others are: Strange fits of passion have I known; I travelled among unknown men; Three years she grew in sun and shower; A slumber did my spirit seal ). Composed during his travels in Germany, Wordsworth may not have been in the best of spirits: he was growing weary of his sister Dorothy, who was travelling with him, instead pining for the company of his friend and collaborator Samuel Coleridge (together the two would formalise Romanticism, about more of which later). It is not known whether Lucy was a real person or a figment of Wordsworth’s imagination: the poet himself would remain forever tight-lipped about her origins. Her real identity, if she even has one, has provoked considerable debate among Wordsworth scholars.

She dwelt among the untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A Maid whom there was none to praise

And very few to love:

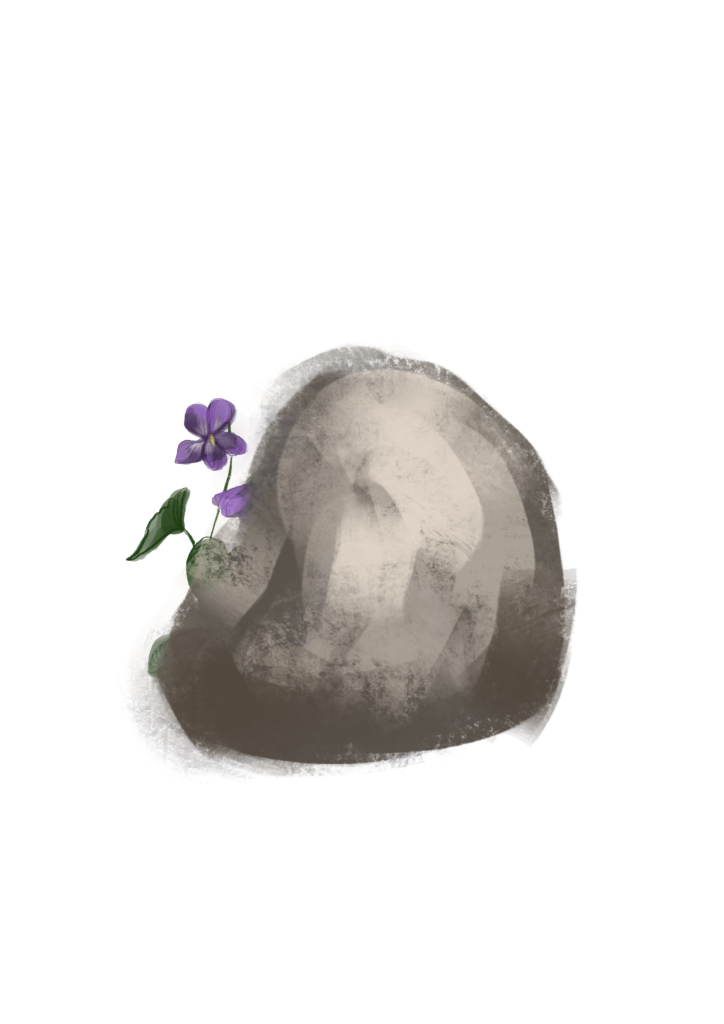

A violet by a mossy stone

Half hidden from the eye!

– Fair as a star, when only one

Is shining in the sky.

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

It’s hard to write about Wordsworth’s poetry without discussing Romanticism. Born in 1770 and raised in Cockermouth (beside England’s Lake District), Romanticism almost certainly had its genesis in Wordsworth’s rural upbringing, in which he spent many happy years enjoying the beauty of nature in this wild and remote part of the country. He would later travel to France and Germany, during which time his Romantic ideas crystallised, and he was able to hone his new style of poetry. Seeming almost too simplistic, we have to remember that Wordsworth’s thoughts about the human condition pre-dated modern psychology and the Freudian idea of the subconscious, by which we understand that experiences in childhood resonate long in the adult psyche. But in Wordsworth’s time, before Freud’s insights, his ideas were highly original; his poetry (along with poems by his close friend and collaborator Samuel Coleridge) caused a sensation in English literature and would inspire a similar revolution in American writing.

Wordsworth’s basic Romantic tenets are that, upon being born, a person passes from an ideal state of grace into an imperfect, Earthly form. As children, they are still strongly connected to their innocent state; but as a person gets older they lose more and more of this ‘purity.’ He suggested that, above all things, children have a closer and more joyous relationship with the natural world. Following his turbulent experiences in Paris during the French Revolution, Wordsworth came to believe that city life accelerated and accentuated the process of losing one’s innocence, making city people ever more selfish and sinful. On the contrary, farmers, labourers and simple country folk were able to retain more of their ‘natural’ selves through maintaining a close association with the natural world. When channelled through his writing, these simple tenets gave birth to Romanticism, a revolutionary school of poetry with brand new conventions of its own.

Chief among these conventions is an idolisation of nature in the purest and most simple terms. When people first read Wordsworth, they sometimes wonder what all the fuss is about! His poems seem so straightforward compared to the convoluted structures and elevated diction employed by earlier poetic traditions, such as the metaphysical poets to give one striking example. With notable exceptions (Composed Upon Westminster Bridge springs to mind) Wordsworth’s poems describe rural scenes (It is a beauteous evening, calm and free), are inspired by trees and flowers (I Wander’d Lonely As A Cloud), or examine something simple and natural like a quirk of the weather (Ode to the West Wind). Look at She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways: apart from untrodden almost all the words are mono-or di-syllabic (having one or two syllables) making the poem extremely simple to read and understand. Simple diction co-incidentally conveys the simple character of Lucy: this is not meant as a slight – Wordsworth revered simple people, as he believed they were much closer to nature, and therefore to the state of grace from which most people have become disconnected.

Although he believed that, as people get older, they lose their ability to connect with nature, as a kind of trade-off they become more adept at understanding the natural world as a metaphor for human life. Therefore, Romantic poetry often provides figurative comparisons between the human and natural worlds. In Wordsworth’s mind these were the ideal type of comparison; both illuminating the true nature of the human soul and reminding his readers of the importance of contemplating nature. In She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways, the second stanza provides two figurative comparisons of Lucy with the natural world. The first metaphor, A violet by a mossy stone, suggests her beauty was unappreciated because it accorded so closely with that of nature. Think about surveying a woodland scene, and how hard it might be to discern a single flower against so much greenery. Granted, if one was to notice the violet, it’s popping vibrant colour would certainly draw praise. Being hidden half from the eye, though, suggests her beauty would have been unappreciated by those unused to such close observances of natural scenes.

The second of these figurative comparisons is a simile: Fair as a star, when only one/ Is shining in the sky. Apart from being objects existing in the natural world, the two comparisons, at first glance, don’t seem very coherent. What have a violet…hidden by a mossy stone and a single star… shining in the sky got in common? Then it becomes clear that the second comparison is a mirror image of the first – a single star is almost impossible to discern and appreciate when hidden amongst all the other twinkling stars. But if it was the only one in the sky? Suddenly its special properties would be clear and easy to see. The second comparison implies again that most people would not, under normal circumstances, have the acuity to see and appreciate Lucy’s beauty. As well, the simile emphasises her remoteness. She’s one of those folk who stayed in close communion with nature, living among the untrodden ways, shunning the company of other people: like a star, the speaker could only admire her from afar.

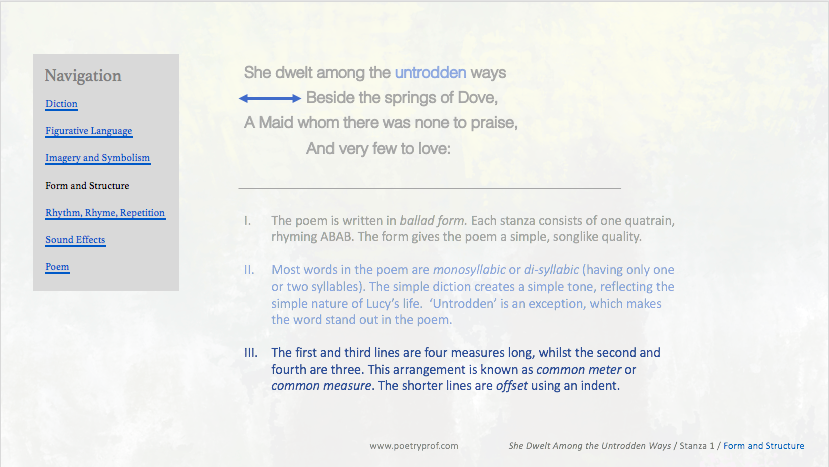

According to Wordsworth’s burgeoning theory, contemplation of the natural world and the recording of ordinary, simple people’s lives and stories was the principle task of Romanticism. He believed that a poet had to follow a certain creative process: firstly, he would have to attain a state of tranquility, perhaps by walking in the countryside (in fact, many of his poems are related by a speaker who seems to be ‘wandering’ aimlessly). Once in this ‘tranquil’ state he would be more attuned to the emotions generated by the natural world; nature became his inspiration. The poet would have to ‘surrender’ their creative impulse to this inspiration; he would later be able to write the poem (Wordsworth and Coleridge both believed it was impossible to compose while still in the grip of emotion; only later, through reflection and contemplation of the experience, could the emotion be distilled into poetry.) Wordsworth’s emphasis was on simple and direct communication of nature’s beauty over poetic ornamentation. That’s why many of his poems seem so simple. Take a look at She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways once more: the form is very easy to describe. The poem is written in three stanzas of four lines each (a verse of four lines is called a quatrain). The rhyme scheme is a simple ABAB, CDCD, EFEF pattern and the rhythm is iambic. Look only a little bit closer and you’ll see that the first and third line of each stanza is four feet long (each measure of an unstressed-stressed syllable is called a foot) and the second and fourth lines are three feet:

She dwēlt/ amōng/ the untrōd/ den wāys/

Besīde/ the sprīngs/ of Dōve,/

A Māid/ whom thēre/ was nōne/ to prāise,/

And vē/ ry fēw/ to lōve:/

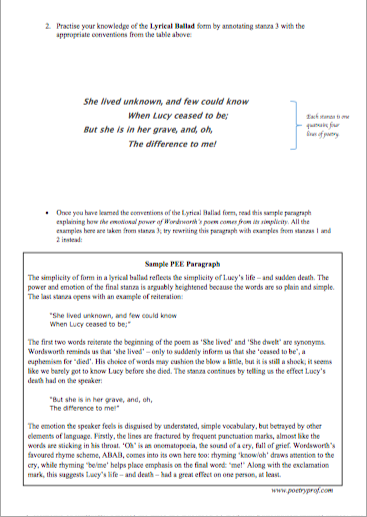

This pattern comprises a simple, traditional form of poetry called a ballad. Deriving from an French oral tradition (ballads were originally lyrics composed to music), the form suggests a simple folk song of the kind Lucy may have sung to herself as she went through her day. The structure and sequence of the poem is similarly simple, inspired by the natural cycle of life and death. The first stanza presents the way Lucy ‘lived’ (dwelt); in stanza one diction associates with youth and vitality: springs are a symbol of freshness and youth; Maid means a young unmarried woman. The last stanza contemplates her death (ceased to be; in her grave). The middle stanza can be read as an appreciation of Lucy as she was in life, seen through the prism of the poet’s unrequited love and admiration. The over-riding simplicity of both form and content was a break with English poetic tradition. Ballads had been used to recount heroic or folkloric tales, mythical or heroic deeds, and used elevated diction. Other great English poets – Milton, for example – had used iambic pentameter to write about lofty subjects and philosophical ideas. Poems such as Paradise Lost and Shakespeare’s sonnets can be placed in an Augustan Tradition, as remote from the style and substance of Wordsworth’s poems as Lucy was from the busy, human world.

In breaking from this tradition, Wordsworth necessarily employed very few ornamental embellishments in his poem. The most obvious is the presentation of alternate offset lines, which hint at the way Lucy lived her life half hidden from view. Eagle-eyed readers will also have spotted the slight rhythmic disturbance caused by the word untrodden. Look closely at the lines reproduced above and you’ll see a rogue anapaest (de-de-dum) hidden among the iambs – again hinting at the way Lucy’s beauty was often obscured (that mossy stone again) to any but the most observant. The anapaest helps call attention to the symbolism of the word: untrodden refers to both her remoteness and the almost intangible details of her life: who she was, what she was like. So too the half-rhyme of stone and one. Words that look like they should rhyme but don’t really are called eye-rhymes; this term again hints at the need for careful observation should one want to understand something fully.

Following the poetic tradition of a turn, or volta, the last two lines shift the focus away from Lucy and onto the speaker himself, in particular to the affects her death has wrought on him. This shift in perspective is marked with a connective, but, after which the depth of his grief at Lucy’s passing is disguised by understatement. Wordsworth occasionally had a tendency to be hyperbolic (check out I wander’d lonely as a cloud if you don’t believe me); that is not the case here:

But she is in her grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

True to his tenets of Romantic contemplation, Wordsworth asks his readers to look more carefully to see the truth of matters. A sequence of three commas after grave fractures the line into pieces (a purposeful break in the middle of a line of poetry is called caesura). That tiny word, oh, is an onomatopoeia rendering his grief vividly audible when read aloud. Given the elegaic tone created by a poem full of soft sounds (half hidden; fair as a star), when hard sounds do appear they tend to get noticed more: both guttural G in grave and dental D in difference convey strong negative emotion. And at the very end the difference to me is emphasised too with punctuation, an exclamation mark Wordsworth’s only concession to hyperbole on this occasion.

To return, then, to my original question – who is Lucy? – I’ve decided it doesn’t matter. At the end of the day, Lucy (the Latin etymology of her name means, fittingly, ‘light’) represents anybody who moves through life quietly, unappreciated, but nevertheless carries their own unique beauty and quality of interest. Wordsworth’s poem helps to shine a light, briefly, on the way such people touch the lives and hearts of others – even if they are never to know it themselves.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802 by William Wordsworth

An exception to much of his oeuvre in that it was inspired by an urban, rather than rural, scene. You’ll soon notice, though, that in his praise of the sunrise over Westminster Bridge in London, he always compares it to the splendour of natural sights: hills, valleys, and wooded glades.

- Frost at Midnight by Samuel Coleridge

Wordsworth’s contemporary and collaborator (they published Lyrical Ballads together in 1798), Coleridge also has an important part to play in the history of Romanticism. In this poem, he says that contemplation of natural scenes can result in the eventual understanding of ‘that eternal language,’ uttered by God, and transcribed for us to read in nature.

- Crazy by Laxmi Pravad Devkota

Famous as Nepal’s first modern Romantic poet,Devkota said his primary influences were Wordsworth and Coleridge. In this amazing poem, translated from Nepali, he closely examines elements of the natural world – I see sounds, I hear sights, I taste smells– striving to comprehend what Coleridge termed ‘that eternal language’ spoken by nature and revealing the truth of the world.

- Romanticism by Billy Collins

I love this poem. Collins is an expert on English Romanticism (he specialised in this area for his doctorate studies) and this poem conflates the notion of Romanticism with a capital R – the solemn observation of the natural world – with a more modern take on the word ‘romantic.’ It begins with the narrator looking at the images decorating books on a shelf – lonely wheelbarrows in the rain, weeping windows, and a dark brooding forest – and goes on to describe his deep sadness after somebody he loves has gone…

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed the analysis and would like to discover more, you could download a bespoke study bundle for this poem. Normally the bundle would cost £2, but this time we’d love for you to check out the kind of resources on offer for free. You can find the bundle for Wordsworth’s poem – and lots more besides– in the shop. The resources include:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on the form of the poem, Lyrical Ballad, the conventions it follows and the effects they create.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What do you think of Wordsworth’s She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways? Do you agree with the opinion that he loved Lucy from afar? How did you react when you read that she had died? How do you interpret the two images presented in the middle stanza? Leave a comment, ask a question, share your ideas below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.