Love really hurts in Aphra Behn’s cherubic rework

“All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn… for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.”

Virginia Woolf (A Room of One’s Own)

A radical 17th century playwright, famously celebrated in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, Aphra Behn made a reputation for herself as a writer who put the bawdy and scandalous right up there on stage – as you’ll see when you read Love Armed. The adopted daughter of the Lord General of Surinam, Aphra lived for a time in the West Indies, returned to England, married mysteriously (her husband was reputedly a Dutch merchant, but he died leaving her his last name, Behn, and a large debt), and was reportedly the first woman in British history to earn a living professionally as a writer, as she worked to clear her late husband’s debts. After spells in a debtors’ gaol and as a spy for the king (yes, really!) she settled as a playwright in London. In fact, today’s poem was written as part of the first scene of a play from 1676 called Abdelazar. Recited in ‘an elegant room’, it sets a terrible scene: a Tyrannic figure looms astride a field littered with broken and bleeding bodies. He is the personification of Love and the fallen are his vanquished victims; the lovelorn, the heartbroken, the pitiable. Pictured like a Roman warlord, this is no cute cherubic figure with a feathery pink bow; Aphra’s portrayal of Love hurls arrows of fire around him with gleeful abandon, striking down more victims and crushing them mercilessly under his heel:

Love in Fantastic Triumph sat,

Whilst Bleeding Hearts around him flowed,

For whom Fresh Pains he did Create,

And strange Tyrannic power he showed:

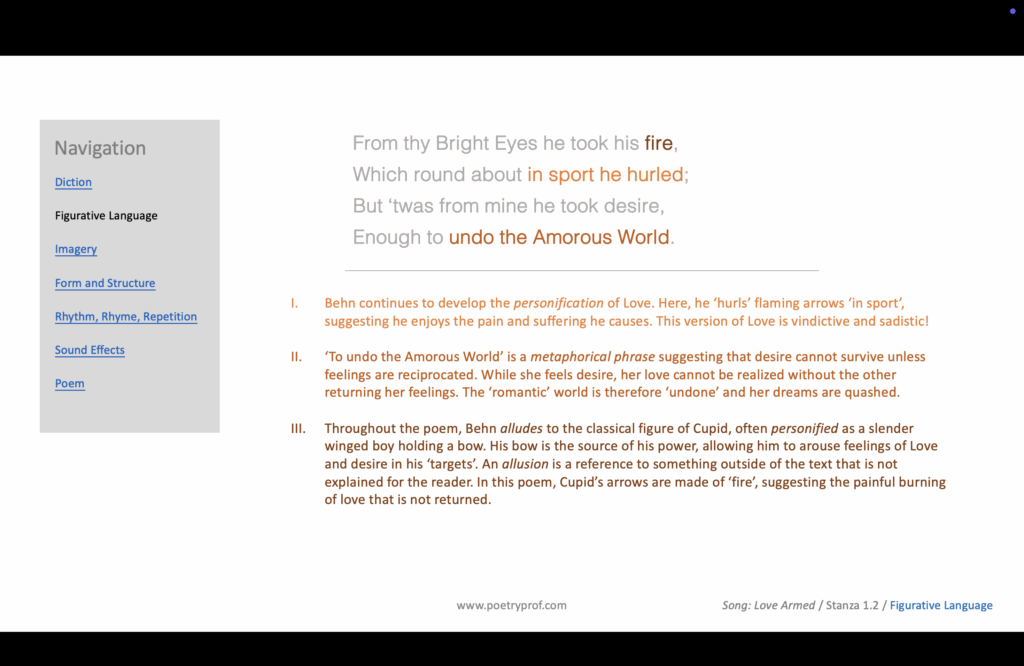

From thy Bright Eyes he took his fire,

Which round about in sport he hurled;

But ‘twas from mine he took desire,

Enough to undo the Amorous World.

From me he took his sighs and tears,

From thee his Pride and Cruelty;

From me his Languishments and Fears,

And every Killing Dart from thee.

Thus thou and I the God have armed,

And set him up a Deity;

But my poor Heart alone is harmed,

Whilst thine the Victor is, and free.

The most striking feature of Love Armed is, of course, Behn’s awe-inspiring depiction of Love. Transformed from the cute image of a cherubic angel from Valentine’s Day cards, here Love is personified as a Tyrannic Roman warlord, freshly returned from the battlefield, gleaming armour spattered with the fresh blood of his enemies. He sits in Triumph, a word that comes from the Roman world and means a ‘splendid parade’ of the sort Roman Emperors would hold to display the spoils of war. However, this parade is a strange and Fantastic one, implying it surpasses even the imperial grandeur of Ancient Rome; it’s so resplendent and grisly that it defies imagination. Later, Love is described as a God and Deity, ascribing him more power than any Earthly ruler, no matter how strong. The imperious picture of a victorious Tyrant is amplified by imagery of fire; having stolen the bright light from another’s eyes he forges this energy into arrows of fire that he hurls indiscriminately so anyone unlucky enough to get struck is guaranteed to get burned. In this poem, love really hurts!

If you dare to tear your gaze away from the Tyrant himself, you’ll be horrified by the devastation around him. It’s more a scene of torture than scene of triumph. Love’s sat, not in calm repose, but in eager anticipation, leaning forward on the edge of his throne, bright eyes hunting for more victims at which he hurls his fiery arrows in sport, a word suggesting that causing pain is a fun distraction for him. Bleeding Hearts lie strewn around, twitching in the throes of agony. Struck down by Love’s fiery arrows (killing dart), they represent a dark twist on the idea of ‘lovestruck’ as blood oozes (flowed) into a grisly pool on the floor. Not content with his victory, like some vindictive sadist, Fresh Pains he did Create to inflict upon the Bleeding Hearts. That’s right – even as the lovelorn hearts lie twitching at his feet, he devises ever more ingenious ways of inflicting pain; in the nature of cruel Tyrants, it’s not enough for Love to have power, he takes delight in wielding it over others. The whole tableau is so grim and dark that it’s Enough to undo the Amorous World, a phrase that’s a little paradoxical, seeming to imply that, despite the overwhelming feeling the speaker experiences, desire can’t survive if the feeling isn’t returned. The idea of the Tyrant taking from others is important in establishing this vision of Love as entirely selfish: Behn repeats the phrase he took three times across both stanzas to emphasise the act of conquest.

The whole picture is given a delicious ironic twist as readers are likely to recognise allusions to Cupid in Behn’s poem. In classical mythology, Cupid is the god of love, desire, attraction, and eroticism. Also known as Amor (meaning ‘love’) and Eros in Greece, Cupid was commonly portrayed as a slender winged boy. But even before Love Armed was written, Cupid was increasingly conflated with the Cherubim, small, winged angels who interceded between Earth and Heaven, and images of Cupid as a small, chubby boy carrying bow and arrow, which are the source of his power to fill others with uncontrollable love and desire, were entering the public consciousness (such as this sculpture made in the 1620s by Francois Duquesnoy). Faintly alluding to well-known iconography, Behn distorts Cupid’s kindly features with malice as he launches yet another Killing Dart at an unsuspecting victim. Less known is Cupid’s parentage; as well as being the son of Venus – goddess of Love – his father is also Mars, Roman god of war. Behn draws out his father’s legacy to portray a great and terrible God of Love couched in the martial diction of war: armed, Bleeding, pains, power, Tyrannic, hurled, Killing Dart, harmed, and Victor are not words naturally suited to composing a romantic ditty.

Hypnotised by the magnetic figure of Love, it’s actually easy to overlook two other important presences in the poem: the speaker herself, who is a part of the scene and been struck by one of Love’s missiles, and her beloved. Unfortunately, while she’s fallen victim to Love’s furious fusillade, her beloved seems to have escaped unscathed. The first hint of a pair of thwarted lovers comes in the fifth line of the first stanza when the speaker mentions thy bright eyes; ‘thy’, ‘thee’ and ‘thine’ being archaic forms of the words ‘you’ and ‘yours’. Throughout the poem, thee or thy is placed in opposition to me, my and mine: at the start of the second stanza, the sense of disconnect between the two intensifies through a pattern of me vs thee in three anaphoric lines: From me… From thee… From me… and a final epistrophe: From thee (anaphora is repetition of words and phrases at the beginning of lines; epistrophe refers to the placement of repeated words or phrase at the end of a line of poetry). The constant back and forth between thee and me creates the impression that never the twain shall meet. Behn’s rhyme scheme comes into its own here: composed in alternate rhyme rather than rhyming couplets, she evokes the impression of two people remaining at a distance from one another.

Alongside the subversion of romantic imagery is a subversion of poetic form. Defined by Behn as a Song, this type of poem was often set to music, entertaining and delighting courtly listeners with pleasurable, musical rhythms and rhymes. But Love Armed is no dreamy love song. If there’s music to be heard here it’s the flourish of trumpets and beating of drums that accompany the return of a victorious army. Love Armed is written in iambic tetrameter, each line composed in four pairs of unstressed-stressed syllables per line, beating out a steady de-dum, de-dum rhythm that, in a more conventional love poem, might evoke the passionate beating of lovers’ hearts. Here it more readily associates with the iron-shod boots of a marching army, as those hearts are ruthlessly trampled upon. There’s something of the Tyrant’s cruel eagerness conveyed by rhythm too: he may be sat in lordly fashion, but his eyes are ever restless, his cruel gaze ever hunting for new victims. There’s an effective rhythmic variation in line one, which inverts the pattern of stresses in the first measure so that the accent falls on the first word Love, asserting his primacy and dominance over the scene (for those of you who are rhythmically inclined, this is technically called a trochaic reversal; a pattern of two syllables arranged stressed-unstressed, the mirror of an iamb, is called a trochee). Equally, rhyme contributes to the poem’s martial feel and asserts Love’s tyranny: short sharp rhymes such as sat/create (in 1676 ‘create’ would have been pronounced as if there was no ‘e’, shortening the vowel to rhyme perfectly with ‘sat’) harmed/armed, cruelty/Deity are accentuated with dental T and D sounds, dominating the poem and ending each line on an emphatic upbeat. In fact, I’d say that hard, dental sounds are the underlying sonic motif of the entire poem, underscoring lines such as Fantastic Triumph sat and But ‘twas from mine he took desire. Made by tapping the tongue against the top teeth, dental creates a cold, crisp, martial footstep that perfectly suits the malicious character of Love, and implies how warm emotions are cast aside, struck down, and trampled upon.

They say that opposites attract, but that’s clearly not happening here. The poem’s speaker paints herself as a soft, delicate kind of person, prone to emotion and suffering from a depth of feeling. From her, love has taken desire, fear, languishments (meaning either ‘weakness’ or a kind of ‘longing sadness’, depending on the occasion), sighs and tears, all either emotions or, in the case of sighs and tears, symbols of emotion. Softness underpins the sound of much of this diction, long vowel sounds such as the ea combination in fear/tears, or the breathy onomatopoeia of the word sigh. On the other hand, her beloved displays a certain heartlessness, characterised by words such as Cruelty, pride, and fire. Indeed, it is the object of her affection from whom the Tyrant took his Killing Dart, words made of sharp stabbing sounds (K, D, T) suggesting that this person, whoever he may be, is more than capable of inflicting wounds of his own. It’s hard to tell from the poem whether the speaker and this other person have had a past relationship that’s turned sour, or whether this is just a case of spurned affection. Clues might lie in the word Cruelty, which faintly implies the speaker has some experience of the other, and in stanza two line five, which is the only line of the poem to feature both thou and I, briefly placing the two side by side. But this is more conjecture than analysis.

The opposition between the speaker and the other represents a longstanding literary tension between opposing forces of reason and emotion, between the Apollonian and Dionysian. In Greek myth, Apollo and Dionysus are half-brothers who couldn’t be more different in character. Apollo stands for rational thinking, reason and logic; his brother for instinct, passion, irrationality and chaos (after all, Dionysus is the god of wine!). Her sighs and tears cast the speaker in Dionysian robes, as does the extreme of her emotional pain: she feels so strongly that the Amorous World is literally undone, a hyperbole that is suitably Dionysian. By contrast, her beloved, cast as the Victor in this tug-of-war, seems immune to extremes of feeling. Perhaps his Pride holds him in check, as if he considers himself above such tawdry emotions? The clash between the two is symbolized through the eyes of the speaker and her beloved. In a brief moment of eye-contact, the fire in the other’s eyes ignited desire in the speaker’s own. Herein lies the interesting speculation that the speaker is drawn to charismatic, volatile men (or women) who are emotionally unattainable and possibly toxic; suddenly, despite being written four centuries ago, Behn’s words might feel wholly relevant to anyone who can’t help falling for the ‘wrong type of guy’ (or girl). Behn’s plays often pitted sharp, spiky female characters against attractive-but-violent or roguish men – and she was not afraid to depict same-sex relationships either. Ideally, a loving relationship arises from a balance between head and heart, both Apollonian and Dionysian traits: Thus thou and I the god have armed and set him up a Deity. But when the two forces are unbalanced, when one or the other rules too strongly, when an excess of Dionysian emotion breaks against the bulwark of Apollonian logic, that’s when things don’t work out.

Song: Love Armed ends as a cautionary tale about the consequences of rampaging, unrequited desire for an unattainable other. While the popular saying tells us ‘all’s fair in love and war’, that’s not true when one party seems armoured against all feeling. The poem leaves us with the bitter message that, if one wants to win in a war of Love, it’s better to close one’s heart and deny one’s impulses. Those who are too open make themselves easy sport for Love’s tyranny… they are the ones who end up alone.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Disappointment by Aphra Behn

Behn developed a reputation as a scandalous writer, unafraid to put the bawdy and explicit on stage or page. In this poem, the amorous Lisander takes fair Cloris, a maid, deep into the woods to enjoy a romantic tryst. Overcoming her protestations, he disrobes her, falls on her in passion – only to find his manhood inhibited by an attack of impotence!

- On Love by Khalil Gibran

This famous Arabic writer, born in Lebanon and influenced by his travels through Europe and America, personifies love in a tender poem beginning with the lovely line: “When love beckons to you, follow him, though his ways be hard and steep…”

- A Leave-Taking by Charles Swinburne

Written when he was twenty-one, this poem conveys the intensity of young love. Swinburne is convinced that absolutely nobody has ever experienced the pangs of rejection as bitterly as he. Sound familiar?

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Love Armed at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining personification.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Aphra Behn’s poem? Do you know any more about her fascinating life? Do you think there might be more to the relationship between the speaker of Love Armed and the unseen object of her affection? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.