Elizabeth Barrett Browning attempts the impossible: counting the ways one person can love another.

“Inspired by the flash of true genius…”

Virginia Woolf

The courtship of Elizabeth Browning (then Barrett) by her future husband Robert Browning could have come, appropriately enough, straight from the pages of a nineteenth century romantic novel. Two volumes of her poetry had caught the public’s attention, and thus found their way onto Robert’s to-read list. On reading Lady Geraldine’s Courtship, a story of how a dashing young poet of limited means but considerable ardour seduced the daughter of an Earl, he must have been quite taken to see one of his own works, Bells and Pomegranates, name-checked (alongside Tennyson, Wordsworth, Petrarch and other luminaries). In January 1845 he wrote a letter to Barrett saying that, “I love your verses with all my heart.” I’m not sure if Robert knew that Elizabeth had an engraving of him on her writing desk! That was the start of a frequent correspondence which soon developed into something more, and inspired this sonnet:

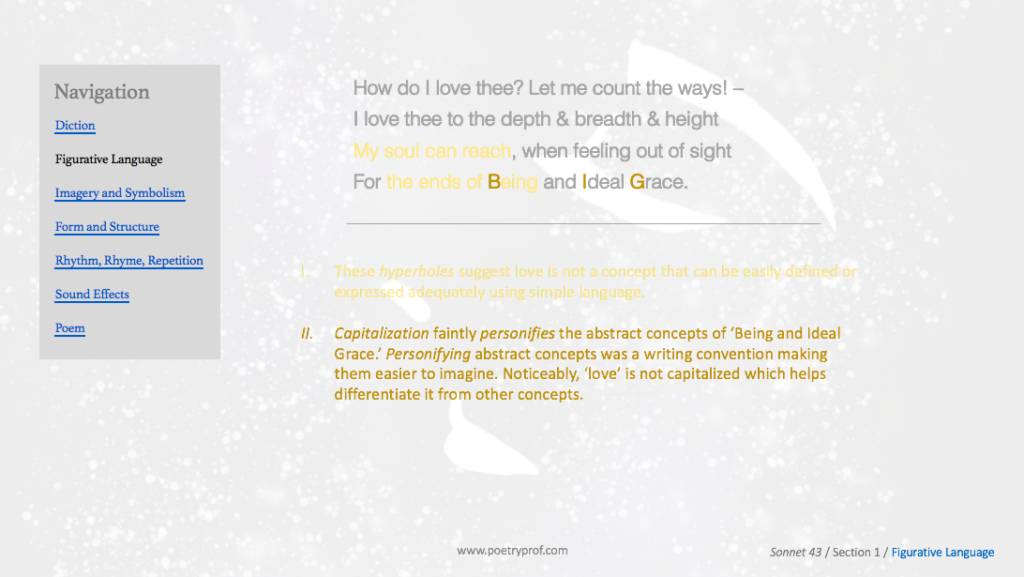

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways! –

I love thee to the depth & breadth & height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and Ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight –

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right, –

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise;

I love thee with the passion, put to use

In my old griefs,.. and with my childhood’s faith:

I love thee with the love I seemed to lose

With my lost Saints, – I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life! – and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after my death.

The full story, including her father’s objections, Elizabeth’s initial reluctance to be more than friends, her success as an emerging writer, their age difference (he was six years younger), her frequent illness, his failure as a London playwright, played out over the next three years. Needless to say, it culminated in a wedding – in secret, naturally – an elopement, and the birth of their only child, Robert “Pen” Browning. While all this was going on, Elizabeth was working on a new collection of 44 poems that she kept to herself before showing her new husband in 1849. He was immediately impressed and insisted upon their publication. In order to avoid any suspicion of autobiography, Elizabeth gave her new collection the title Sonnets from the Portuguese and pretended they were translations. Over time, this collection gradually became the most beloved of all her works – and the most beloved of those 44 poems might be Sonnet 43.

One reason the appeal of this sonnet is so strong is it attempts something that many of us have probably tried to do at least once in our lives: put a solid definition on the abstract concept of love. Sonnet 43 tries to answer those age-old questions: What is love? What does it mean to be in love? It’s one of those talks you have with a group of friends at the end of a party, when you’ve stayed up too late and are feeling particularly garrulous. You know that phrase, ‘words can’t describe how I feel’? In this poem, Browning tries to find those words.

It’s important when reading all poetry not to fall into the trap of thinking the speaker and the poet are the same. A novelist creates characters; a poet creates speakers or personas. Strictly speaking, the speaker in the poem is not Elizabeth Browning – she’s a representation of Browning’s ideas. Her voice helps Browning explore the idea, How do I love thee? Having said that, in this case the poem is strongly autobiographical, and ‘thee’ is her future husband, Robert Browning. Remembering that you’re hearing the voice of a persona when you read, however, might help you appreciate why the poem has retained such popular appeal for so long; readers feel like this poem relates a universal concept of love as experienced by more people than just her. Maybe you don’t love in all the different ways Browning counts, but perhaps you can relate to some of them.

She sets out her stall in the very first line, a bold statement of intent:

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways! –

Often, when trying to explain an abstract concept, writers will use comparisons – especially similes which help simplify their feelings: “I love you like a fish loves water,” “I love you more than anyone else in the world,” “I love you like the sun.” Or they might use synonyms to clarify the exact degree of feeling: ‘passion,’ ‘attraction,’ ‘infatuation’, ‘brotherly love’ and so on. What’s surprising about this poem is that Browning repeats I love you eight times (beginning lines with a repeated pattern of words is a special kind of repetition called anaphora) without variation. The word love is repeated ten times in total. She never changes the vocabulary of this expression. These repetitions suggest that the quality of true love is pure and unchanging: there is only one kind of love.

Think about this point for a moment. If love is so constant, why do we then even have synonyms and similes like ‘attraction,’ ‘passion,’ ‘lust’ and the like? What Browning’s poem suggests is that, while love is unwavering, a person will change over the course of a life. Equally, there are many types of relationship: intimate or aloof; physical or platonic; smooth or rocky. One relationship can evolve over time: two people might be young and passionate then grow old and comfortable. Through all the stages and changes of life though, Browning argues, her love will never diminish. When reading the first line, pay close attention to her phrasing: Let me count the ways, not ‘types,’ of love. Loving someone is like passing pure water through a hose. You can spray, shower, squirt, trickle, drip, drizzle, drench or jet – but what comes out is always H2O.

The upshot of all that is the sonnet doesn’t tell us much more about love than, “it’s constant.” Through that persona though, we can sense little glimmers of Browning’s life and personality. This is one of writing’s chief powers – it can freeze thoughts and feelings in a time capsule that we can sift through like archaeologists to discover how somebody lived and loved almost two centuries ago. We can share her experience of what love feels like and realise that the way we love people today is not so different from people in the past.

Take the first few lines:

I love thee to the depth & breadth & height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and Ideal Grace.

She begins by trying to describe the physical shape and size of her love. Depth & breadth & height might seem strangely cold ways of loving, a loveless spatial description capturing emotion in the language of mathematics. But see how she starts measuring… then quickly says love cannot be measured! The dimension of her love is the same size and distance that her soul can reach. How far is that? Up to you, but one idea is that it stretches infinitely far. Granted, that seems like hyperbole, but love often feels like that. Like the universe, no matter how far you can imagine her soul reaching, love extends beyond this point (out of sight). After the comma right in the middle of line 3, Browning stretches the hyperbole even further by creating an image of herself feeling in the dark to express how love extends beyond her grasp, or ability to describe. Close your eyes and grope the space around you – it’s easy to relate to this image and understand how she feels. Love fills up space right to the edges of the known universe, and beyond: it extends to the ends of Being and Ideal Grace.

After this bold beginning, Browning dials down the intensity, presenting a quiet vision of love. If the first four lines are the passionate feelings of an early relationship, these two are the way a couple can spend time together everyday and still experience that insistent tug of the heartstrings:

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight –

How does she manage such a drastic change of tone between lines? Well, first she simplifies her sentence structure: the list depth & breadth & height is replaced by a simple, single word: level. All those ampersands (the little ‘&’ symbol that connects items in a list; a grammar structure called polysyndeton) are gone. The effect is to take all the hyperbole and intensity out of her voice and make it quiet. The images are simplified and restrained too: sun and candlelight are immediately more concrete than the infinite expanse of the soul. Nevertheless, they communicate love’s constancy: loving someone by both sun and candlelight means loving them through day and night, all the time: sometimes the feeling is huge, overwhelming, like the sun; sometimes it smoulders comfortingly, like a candle in a dark room. And, the eagle-eyed amongst you will already have noticed not all the hyperbole has vanished: most quiet is a hyperbolic understatement (hyperbole encompasses ‘least’ as well as ‘most’).

Like an archaeologist uncovering that imaginary time capsule, you need to dig a little to find something about Browning’s moral framework. She loves Robert as men strive for Right and turn from Praise. In context, Right means upholding certain values: Browning’s second book of poetry contained the poem The Cry of the Children (telling of the pitiful lives of children working in manufacturing, mining, textiles and industry). A Curse for a Nation is a fervent antislavery poem; these examples give you a good idea of what she might consider strive for Right to mean. Turn from Praise is easier; it suggests modesty and the reluctance to bask in the adoration of others. We can imply that she loves Robert honestly and selflessly, not expecting anything in return. You may wonder why she capitalises words like Praise, Right, Grace and Being; this is a convention of the time. Poets often personified abstract concepts through capitalisation, perhaps to help conceptualise them. In light of this, it may be noteworthy that ‘love’ is never capitalised: in this poem at least, it sets love apart from other concepts one might experience, again suggesting it defies simple description through personification.

The following lines give us an insight into Browning’s personal history:

I love thee with the passion, put to use

In my old griefs,.. and with my childhood’s faith:

I love thee with the love I seemed to lose

With my lost Saints,

Remember the warning not to read poems autobiographically? Take lost Saints, for instance. Browning spent many years idolizing her mentor Hugh Stuart Boyd, a sort of faded, scholarly wastrel who encouraged her to pursue Greek and study the classics. Later in her life she would become disillusioned with him, writing in a letter that works composed under his tutelage were ‘frigid’ and ‘rigid.’ Might he be an old grief orlost Saint? Equally, lost Saints might refer to her favourite brother Edward, who drowned in July 1840, leaving her so bereft she wouldn’t leave her house. We can only speculate. I think the experience conveyed by the poem, though undoubtedly biographically true, is at the same time universal. Old griefs can be applied to any great loss a person can experience. You don’t have to know who Hugh Stuart Boyd was to sympathise with the idea of outgrowing one’s childish naivety, or to feel keen disappointment. Too, don’t overlook the word seemed hidden in the line the love I seemed to lose. If you have ever thought you lost something – or somebody – precious to you, only to be reunited again later, then you can understand how love can encompass both keen pain and euphoric joy.

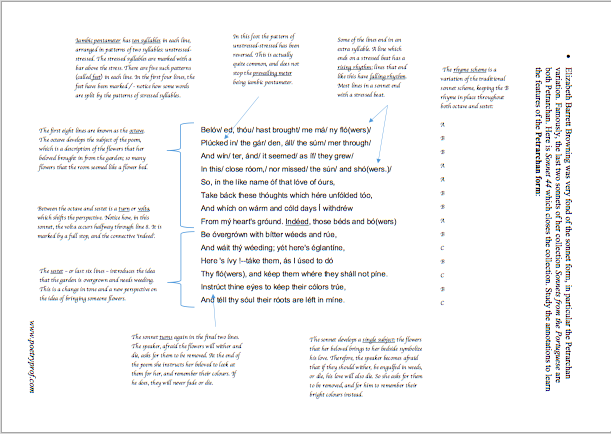

We haven’t much discussed the form of the poem, except to note that it’s a sonnet; this is particularly apt for Browning’s How Do I Love Thee. In Italian, sonnet means ‘little song’ and is a form of lyric poetry, perfect for exploring meanings and expressing emotions at the same time (think of how a song might create ideas through words and feelings through melody). Two forms of sonnet – Petrarchan and Shakespearean – helped associate the sonnet with love poetry: Petrarch, in particular, was a fourteenth century Italian love poet. Browning chose to use the Petrarchan sonnet form for Sonnet 43: it has a tighter rhyme scheme, ABBA, ABBA, CDCDCD requiring only four sounds to end all fourteen lines (a Shakespearean sonnet requires seven different sounds arranged in an ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG pattern.) The unity of sound suggests closeness and intimacy, both of which she comes to share with Robert. Sonnets are usually composed in iambic pentameter, a regular de-dum, de-dum rhythm that associates easily with heartbeats and therefore love. Not to forget, the sonnet has a long and distinguished literary tradition in English poetry. As an emerging poet, it would have been necessary for Browning to grapple with this form, a bit like how, if you want to be a really good musician, you have to master your scales.

What the sonnet form also demands is a volta or turn; a moment in the poem where there is a shift in the course of the argument or a ‘refreshing’ of imagery. Shakespeare liked to turn in the final couplet; Petrarch arranged his sonnet in an initial eight lines (the octave) and a following six lines (sextet) between which he liked to turn. The volta is often (but not always) pinpointed by the change in the rhyme scheme or a connective (yet, but, alas, thus and the like). To be honest, many sonnets don’t necessarily signpost their turn so precisely. You might argue there are two possible places where Browning’s Sonnet 43 turns. The first is between the octave and sextet. The semi-colon at the end of line 8 (after Praise😉 signposts the volta. Before this point Browning was describing the abstract concept of love in a universal way: yes, she still usedI love thee, but her descriptions were not necessarily personal only to her. After the semi-colon, she uses examples from her own experience (old griefs, lost Saints).

You might agree that the turn in the following lines, at the end of the poem, is more in keeping with the spirit of a volta, even if the position is not exactly Petrarchan:

– I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life! – and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after my death.

Both the hyphen (–) and if God choose signal the turn formally. And the final line certainly shifts the perspective: Browning argues that even death will be no barrier to loving. In fact, it will only give her the opportunity to love better. As a final observation, the last lines also suggest that her love is not as infinite as the initial images in the poem made it seem. She accepts that her obeisance to god (if God choose) would limit her ability to love under these circumstances, and counterbalances the somewhat hyperbolic intensity of these last couple of lines.

This turn – the requirement to shift perspective, or change the direction of an argument, or describe something anew – is what gives the sonnet so much of its power. Reading a sonnet, you’re almost waiting for the change to happen, wondering where the poet might take you. Re-reading Sonnet 43, I was wondering about that phrase if God choose. All the while it seemed that her love was limitless, reaching as far as a soul can reach. Then, out of nowhere, she seems to check herself, and accept that the promise to keep loving even after death isn’t fully hers to grant. It’s a bittersweet ending to one of the greatest love poems of all time.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare

Most people can recite the first one or two lines of Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer’s Day… but then they get stuck. Have a look for yourself to see how the poem continues.

- A Red, Red Rose by Robert Burns

Like Elizabeth Barrett’s poem, this is addressed to an unseen listener. Unlike hers it’s written in Scottish dialect. Read the poem aloud to fully appreciate lines such as: I will luve thee still, my dear, Till a’ tha seas gang dry.

- Unending Love by Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore loves with the fervour of the songs of every poet past and forever in this amazing love poem. Beat that, Elizabeth Barrett!

- Love Sonnet XI by Pablo Neruda

Sonnets are hundreds of years old and were flourishing on the continent before being brought to England in the sixteenth century. Translated from the original Spanish, this is a reminder that the sonnet has its roots elsewhere before being popularised by English poets.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Sonnet 43 at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed the analysis and would like to discover more, you could download a bespoke study bundle for this poem. The bundle costs only £2 and you can find the bundle for Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem – and lots more besides– in the shop. The resources include:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on the form of the poem, Petrarchan sonnet, explaining the traditional conventions of this sonnet variation.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What do you think of Browning’s Sonnet 43? Do you recognise any aspects of love she describes? What do you think of the end of the poem? Why do you think the poem has had such lasting appeal? Give your opinion of the blog, ask a question, share your ideas in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Wow

One of the best analysis of the sonnet! I wish I could find this during my exams 🙁

Hi Safiya,

Sorry if we were a bit late for your exams – I bet you did really well anyway! Thank you for your kind message.