Percy Bysshe Shelley wrestles with depression in a poem that seems to anticipate his own destiny.

“…an angel who imprisoned in flesh could not adapt himself to his clay shrine…”

Mary Shelley

If you know anything about the extraordinary life – or, more accurately, death – of Percy Bysshe Shelley, you’ll find it hard to read today’s poem without a little chill running down your spine. Entitled Stanzas Written in Dejection near Naples, it was composed in December 1818 and describes a speaker (certainly representing Shelley himself), who lies down by the shore of a vast ocean and imagines himself drowning as the waves cover him over. Incredibly, Shelley would actually die by drowning just a few short years later (in 1822) when his boat overturned in a storm near his friend’s house in Livorno. One may never know, but it’s hard to escape the impression that, writing these words, the poet may have been prefiguring his own tragic death:

I

The sun is warm, the sky is clear,

The waves are dancing fast and bright,

Blue isles and snowy mountains wear

The purple noon’s transparent might,

The breath of the moist earth is light,

Around its unexpanded buds;

Like many a voice of one delight,

The winds, the birds, the ocean floods,

The City’s voice itself, is soft like Solitude’s.

II

I see the Deep’s untrampled floor

With green and purple seaweed’s strown;

I see the waves upon the shore,

Like light dissolved in star-showers, thrown:

I sit upon the sands alone, -

The lightning of the noontide ocean

Is flashing around me, and a tone

Arises from its measured motion,

How sweet! did any heart now share in my emotion.

III

Alas! I have nor hope nor health,

Nor peace within nor calm around,

Nor that content surpassing wealth

The sage in meditation found,

And walked with inward glory crowned –

Nor fame, nor power, nor love, nor leisure.

Others I see whom these surround –

Smiling they live, and call life pleasure; -

To me that cup has been dealt in another measure.

IV

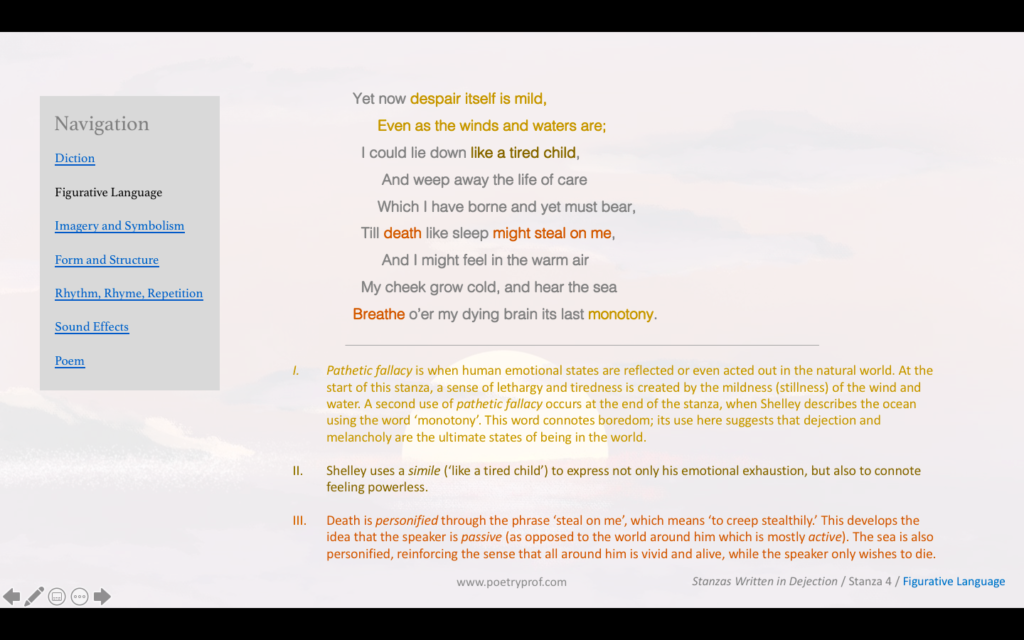

Yet now despair itself is mild,

Even as the winds and waters are;

I could lie down like a tired child,

And weep away the life of care

Which I have borne and yet must bear,

Till death like sleep might steal on me,

And I might feel in the warm air

My cheek grow cold, and hear the sea

Breathe o’er my dying brain its last monotony.

V

Some might lament that I were cold,

As I, when this sweet day is gone,

Which my lost heart, too soon grown old,

Insults with this untimely moan;

They might lament – for I am one

Whom men love not, - and yet regret,

Unlike this day, which when the sun

Shall on its stainless glory set,

Will linger, though enjoyed, like joy in memory yet.

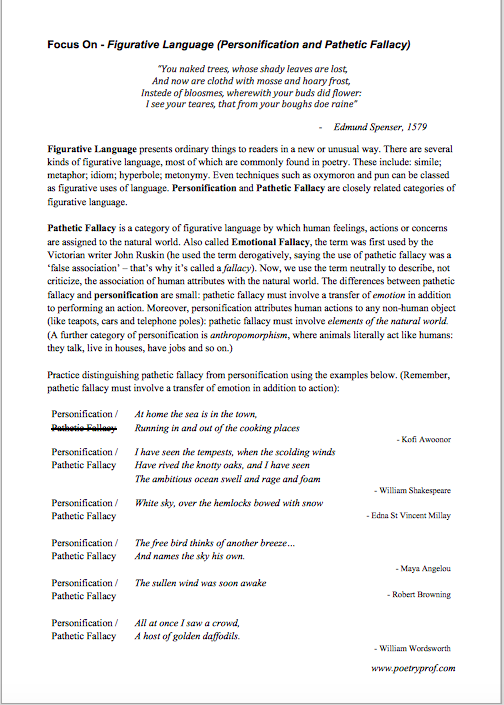

Given this is supposed to be a poem about dejection, it begins with a surprisingly joyful scene of the world as viewed from Shelley’s position as he stands by the seashore. Almost the whole of the first stanza communicates a sense of effervescent life and beauty in the world. Images flow breathlessly, painting a colourful picture: blue, purple, bright and light are all strongly visual words. Shelley personifies almost all the aspects of the scene laid out before him: the waves are dancing, the mountains wear a purple colour, the wind and the City behind him both have a voice and the earth has breath, gently exhaling a soft mist into the air. The cumulative effect of so much personification is the vivid impression of life – the world is alive as a person can be alive. One image of the soil nurturing small unexpanded buds is particularly fertile, as if the buds are babies in the womb, waiting patiently to unfold their limbs and throw out new shoots. The whole scene is vivid and life-affirming, and serves as both a counter-point to, and explanation of, Shelley’s dejection; it’s because he feels alienated from such beauty that he feels so sad. It’s not until the final word of the first stanza – the personification of the emotion Solitude – that this alienation becomes apparent.

Structurally, the first stanza has a classic build-up structure where each part of the scene he describes is like an item in a list. Shelley controls the pace of this list expertly, beginning with slow, measured descriptions in standard grammatical structures (subject – verb – adjective: The sun is warm, the sky is clear) then accelerating towards the end of the stanza by removing verbs from his clauses: the winds, the birds, the ocean floods. Joining items in a list using commas (rather than a connective like ‘and’ or ‘or’) is a technique called asyndeton and this is partly what helps generate the feeling that we’re being guided expertly towards the last word of stanza one. When it arrives, it’s almost disappointing, the anti-climactic word Solitude’s undercutting the anticipation created in the build-up, and giving the reader a small taste of the dejection that Shelley feels as he sits all by himself, unable to participate in the happiness of the scene before him. The feeling of disconnection between the word Solitude‘s and the rest of the stanza is accentuated using rhyme: Solitude‘s half-rhymes with buds and floods (compare this to the full-rhymes of bright / might / light / delight). Shelley was convalescing in Italy at the time he wrote this poem. Although he was with his second wife (Mary Shelley) and friend (Lord Byron, also a renowned poet) amongst others, he was in ill-health. As we’ll discover later, given a recent series of personal disasters in his life, it is not hard to imagine that, even in the company of others, Shelley would feel loneliness and alienation.

Solitude‘s, then, is the pivotal word about which the first two stanzas hinge; narrowing from an expansive description of a world bursting with life, our gaze becomes aligned with Shelley’s speaker, staring fixedly at the ocean ahead of him. For a moment it almost seems like he transports himself to the ocean floor, removed from the world and surrounded by seaweed strown (‘strewn’ means to be scattered around), as if he’s hiding down there in the cold and dark. Careful reading tells us this isn’t quite right – he sits upon the shore alone looking at the play of sunlight on the water, imagining that his gaze penetrates right down to the seabed. But the simile like light dissolved in star-showers imagines the play of light looks like shooting stars in the night sky. It’s a beautiful use of language, and the word dissolved momentarily betrays Shelley’s desire to plunge into the water, obliterating himself into tiny atoms and thereby escaping from the life of cares waiting for him to return to. Diction reinforces this impression; where stanza one gave us Solitude, stanza two contains alone. The word untrampled describes an underwater world where nobody has ever trodden. The need for some kind of escape is also carried by sound; sibilance (seaweed strown; sitsupon the shore; dissolved in star-showers) allows the sound of the sea to drown out all other noises, and creates the soft hiss of the speaker fizzling into nothingness by dissolving in water.

The next few lines transitions the focus of the poem from the external world around the Shelley to his own internal landscape. More than this, the end of the second stanza also develops the idea that, despite the evident beauty of the world and his expressed desire to seek refuge amongst the seaweed at the bottom of the ocean, he actually stands in opposition to – apart from rather than a part of – the natural world. First those star-showers transform into the lightning of the noontide ocean flashing, a vivid image of conflict and danger. Second is his contemplation of the measured motion of the waves; as he looks and listens, he becomes conscious of a tone, or sound, to which he seems particularly sensitive. It’s this sound that seems to embody Shelley’s dejection; he says, rhetorically, did any heart now share in my emotion – as if his experience of the sadness that lies under the illusion of a beautiful and joyous world is unique. (These lines remind me of a poem I wrote about a while ago, Dover Beach, in which Matthew Arnold’s speaker listened to the sound of the ocean and could hear only the eternal note of sadness and a long, melancholy roar. Might Arnold have had Stanzas Written in Dejection in mind when he wrote his own poem set by the side of a bleak and forbidding ocean?)

The first word of the third stanza – Alas! – completes the move from external to internal contemplation (it links with emotion, the final word of stanza two). From this moment, the rest of the stanza is devoted to a description of the speaker’s emotional emptiness – his inner landscape is flat and featureless, a perfect contrast with the natural world’s soaring mountain tops and plunging ocean depths:

I have nor hope nor health,

Nor peace within nor calm around,

Nor that content surpassing wealth

The sage in meditation foundThis sequence functions like a black-and-white negative inversion of the first stanza, the key feature being negation (that little word ‘nor’, repeated five times) which creates such a powerful impression of lacking or emptiness. Most of the things negated, like hope and health and so on, are easy enough to understand – later in the same stanza Shelley lists fame, power, love, and leisure, purposefully negating each one, taking the total uses of the word nor to nine! Interestingly, everything he feels a lack of is an abstraction; the speaker doesn’t mention a single material item. He even rejects the happiness accrued by wealth as something that can be surpassed by the kind of contentment that a wise person (sage) can achieve through meditation. This might lead us to believe that he doesn’t lack for any material belongings (in fact Shelley was born into a comfortable family; the ‘Bysshe’ in his name comes from an aristocratic grandfather, although he was, by 1818, suffering some financial hardship). Rather, it’s spiritual and emotional contentment that Shelley is missing. The sixth line of the stanza, as we saw before, features asyndeton again, which creates the impression Shelley’s troubles pile up relentlessly, come thick and fast, and are overwhelming. Go back up to the first line of stanza three and notice all the aspirant alliteration: created using the letter H, aspirant often resembles a release of breath and is therefore excellent at suggesting a release of (negative) emotion. Say the line out loud, expelling as much air as you can on the words have, hope and health to hear the emptiness inside that Shelley is trying to convey.

The way the speaker feels dislocated from the world of people (the human world as well as the natural world) is developed strongly at the end of the third stanza, where all around him he sees smiling faces, but doesn’t feel any happiness himself. There’s the hint of a sneer in the words smiling they live, and call life pleasure, as if other people exist inside a happy delusion, deaf to the morose tone of the ocean that only the speaker can hear. Do I discern a touch of condescension in his tone of voice? Whether yes or not, Shelley distances himself from other people by creating a ‘them and us’ opposition – the words I, me and my oppose the word they – you won’t find ‘we’, ‘our’ or ‘us’ anywhere in the poem.

After all the abstract language, the third stanza ends with a concrete metaphor; Shelley refers to his own dismay as a cup that has been dealt in another measure. I’m sure you recognise the whisper of ‘cup half-full’ or ‘cup half-empty’ in this use of language too – there should be no doubt as to which is the speaker’s current attitude towards life. His use of diction, particularly the word dealt, is notable here – Shelley wrote this poem at a time of considerable personal unhappiness following a series of tragedies that would overwhelm even the hardiest of people: his first wife and his half-sister had both committed suicide; his two children from this marriage were estranged from him; his father had disinherited him because of his second marriage to Mary; his poetry was being poorly received – and tragedy had again recently struck when his and Mary’s daughter, Clara, died of illness in September 1818. There may have been a nagging doubt in the back of Shelley’s mind that he was indirectly responsible for Clara’s death; he had insisted upon this trip to Italy where he had hoped the climate would be more healthful for him and his family. The line my cup has been dealt in another measure implies that fate and chance have conspired against him to make his life thoroughly miserable. It’s often not advisable to try to glue a poem too tightly to the biography of its writer, but in this case many of the happy qualities that the speaker of the poem lacks allude to Shelley’s real-life difficulties. Fame, for example, probably refers to the critical maulings his poems were taking; he was in poor health and may have felt particularly power-less after Clara’s death.

After taking all this trouble to convey his deep dejection, stanza four opens with a word that signals a turn – a change in the line of reasoning that Shelley is developing. This is not an unusual structural feature in itself – often you’ll read poems that develop beyond their original idea and feature one or more turning points, changes in direction, subtle alterations in tone, argument or some other shift. Readers of sonnets are trained to look for the turn (also called a volta) between the eight and ninth lines, or before the final couplet, and poets often mark the turn with a helpful connective (‘thus’, ‘but’, ‘yet’, and so on). Shelley gives us yet as the first word of the fourth stanza; Yet now despair itself is mild. Look how the argument or direction of the poem is altered by this line; having read three stanzas that created the impression dejection (called despair here) is more powerful than happiness, powerful enough even to undermine joy in the miraculous and resplendent world around us, we now see that Shelley can barely experience despair as well – calling it mild! Perhaps the tragedies leading up to this point had beaten him down and deadened him to feeling anything at all – neither happiness nor sadness? Stanza four is full of words suggesting this unbearable lethargy (lie down, tired, weep away, sleep, cold). He admits in vague terms to his life of care and gives us the impression that he is exhausted by suffering under the weight of the heavy burdens listed above. We didn’t discuss the word transparent (in the first stanza) but it seems to me that this word really pays off here – the speaker seems like a barely tangible presence, totally lacking in energy and vitality, as if he’s already half faded away.

In a way, stanza four is a reiteration of the second stanza’s desire to escape by dissolving in the waves, but the tone is more explicit here – Shelley’s speaker uses the words dying and death directly, and even imagines what his own death might look like. You can compare the verbs used to describe his own actions in stanza four with actions attributed to people and things elsewhere in the poem. Shelley’s speaker can lie, weep, grow cold, and bear the pressures of life upon his young shoulders. He describes himself like a tired child and is almost completely passive. A simple contrast between the warm air and his cold cheek highlights his acute feeling of alienation from the lively world around him, which, as has been seen, is characterised by personification. There’s more here when the sea breathes and in the line death like sleep might steal on me, in which the speaker is so lethargic he can’t even muster the energy to end his own life, instead passively lying there waiting for the personified waves to wash over his inert body. The image of him pressing his cheek into the sand betrays a desire to leave a mark or make an impact on a world that seems indifferent to his actions and pain. Look carefully at the modals in this stanza too (words that communicate strength of feeling or degrees of certainty): could, might and might are among the weakest modals one can choose to use. In fact, Shelley uses a strong modal only once, when he refers to a future full of the same hardships he suffered in the past: which I have borne and yet must bear. You won’t be surprised to learn that it is reported Shelley did have suicidal thoughts during his stay in Naples.

Several ideas we have already discussed come to a head in the poignant final stanza. That feeling of alienation from other people is evident when the speaker pointedly admits that others find him hard to like: for I am one whom men love not. He would like to imagine that some people would be sad upon his death (some might lament) – but don’t forget to take note of the little modals again; might conveys doubt rather than any sense of certainty. His alienation from others is represented by form as well. The poem is written in stanzaic form, where each of the five stanzas contains nine lines (a stanza of nine lines is traditionally called a Spenserian stanza, after the poet who popularised a nine line verse); the first eight lines are written in iambic tetrameter (four measures of two syllables arranged in a de-dum, de-dum pattern). You have probably already spotted that the final line in each stanza is longer – six iambic measures in fact (technically called an alexandrine). It’s not hard to imagine why Shelley may have pressed the Spenserian stanza into use – the last line stands out and is isolated from the previous eight in a way that represents his own feelings of alienation from those around him.

More powerful than his alienation from people, though, is the renewed sense of opposition to the natural world. He describes his own heart as lost and old and imagines how it insults the beauty of the day with an untimely moan. Conversely, the day is described as sweet and possessing a stainless glory. The word stainless once again suggests that, no matter what he attempts in his life, he’ll leave no mark or blemish on a world that exists on its own terms, with or without him there. From Shelley’s point of view, it must have seemed like the whole world was against him, so this fatalism is understandable. There’s another curiously predictive element to the description of his heart as old: a few years later, just before he died in 1822, he remarked to his friend, Leigh Hunt, “I am 90 years old.“

The very end of the poem is worth considering for a moment, as it seems to admit to a shred of positivity that still survives in his barren emotional landscape. The phrase like joy in memory yet admits to a tiny hope – that his memory would bring some joy to others. Admittedly, this joy would be powered by regret at his death – but it’s still positivity of a sort! Shelley imagines that regret can linger beyond the end of the day (which will vanish once the sun goes down). Like the image of pressing his cheek into the sand, the end of the poem therefore seems to betray his deep hope that he will leave something in the world that is worthy of remembering.

I wonder if Shelley would have been comforted to know that, despite the unkind critical reception to his poetry during his life, we are still reading his Stanzas Written in Dejection two hundred years after his untimely death.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Alone by Edgar Allan Poe

In the tradition of the English Romantics (like Shelley) Poe broods over his solitariness. Just like Shelley, Poe was young (only 21) when he wrote this poem, and he too would die before his time – at the age of only 40. Feeling like a misfit among others, Poe looks around him to the natural world for the source of his loneliness, finding nightmarish shapes in the clouds… This is the perfect companion piece to Shelley’s Stanzas Written in Dejection.

- A Sad Child by Margaret Atwood

This is a very different kind of poem; modern, direct, told from the point of view of a mother to a child who believes she’s not the favourite – and more; believes her sadness is unique. It’s the perfect riposte to Shelley when he asks at the end of stanza II whether only he can feel such depth of emotion.

- Sonnet 29 by William Shakespeare

Part of his Fair Youth sonnet sequence, Shakespeare’s speaker also feels outcast and alone. However, thinking of the one he loves is the perfect tonic for his negative emotions.

- Ode on Melancholy by John Keats

Arguably the epitome of all poems on the subject of sadness, Keats’ incredible ode is almost like a how-to guide on coping with feelings of dejection and despair. Keats’ secret is to understand that in all joyful things there is the seed of despair, as illustrated by the metaphor of a man who bursts a fine grape on the roof of his mouth, only to taste the sadness hidden within.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Stanzas Written in Dejection at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining personification and pathetic fallacy.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you like this breakdown of Shelley’s Stanzas Written in Dejection? What do you find interesting about his relationship to the natural world? Does his sad story move you in any way? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Thank you so much for this beautiful analysis!

You’re welcome, Milena. Thank you for your kind comment.