Gerard Manley Hopkins explores what it feels like to be trapped in your skin.

“The reader must have courage to face, and discover… great beauties.”

Robert Bridges

Before getting into today’s poem proper, it might be useful to relate a little of Hopkins’ religious background first. Brought up in an Anglican family, he was earmarked for the priesthood in his early life. He later argued with his family over his conversion to Catholicism, and was to abandon the priesthood for a career in the creative arts. Nevertheless, he practiced his faith throughout his life. Some of his most famous poems, such as The Windhover and Pied Beauty glorify God’s creativity as displayed by the marvels of nature, his finest creation. Poems like these – and today’s poem, The Caged Skylark – can be read in the literary context of the eulogy, religious poetry praising God, while also advancing the beliefs that he inherited from his father: nature is a book written by God, so by focusing on and appreciating nature, one is also contemplating and thanking God.

As a dare-gale skylark scanted in a dull cage

Man’s mounting spirit in his bone-house, mean house, dwells –

That bird beyond the remembering his free fells;

This in drudgery, day-labouring-out life’s age.

Though aloft on turf or perch or poor low stage,

Both sing sometímes the sweetest, sweetest spells,

Yet both droop deadly sómetimes in their cells

Or wring their barriers in bursts of fear or rage.

Not that the sweet-fowl, song-fowl, needs no rest –

Why, hear him, hear him babble and drop down to his nest,

But his own nest, wild nest, no prison.

Man’s spirit will be flesh-bound when found at best,

But uncumberèd: meadow down is not distressed

For a rainbow footing it nor he for his bónes rísen.

The Caged Skylark, though, is not exactly a eulogy. For starters, the octave (first eight lines of a sonnet) conveys despair at the poverty of the human condition; our souls are scanted (this word originally means to be neglected or abandoned) inside our bodies, or bone-house, as Hopkins morbidly puts it. Despite the confines of body and cage, both man and bird are still capable of wondrous self-expression; the belief that man’s divine soul naturally strives to exceed its base condition is suggested through man’s mounting spirit and in the aural image of singing sweetest, sweetest spells. It’s just that the cage restricts these moments, permitting only a glimpse of man’s true potential to shine through the bars. Most of the time we exist in drudgery… labouring-out-life’s age. This is a far cry from the kind of language and imagery we might expect from a religious man who often used his poems to praise God’s works. Hopkins, however, is famous for using the sonnet form to release verbal – and spiritual – energy. In 1885 he wrote a sequence of six sonnets which have become known as the ‘terrible sonnets’ – poems filled with self-loathing, darkness and doubt. It has been said that Hopkins even wrote one of these sonnets in blood! While not one of these six, The Caged Skylark shares some DNA with the terrible sonnets in that it depicts mankind as trapped in an inescapable body.

To be perfectly honest, by 1877, putting a bird in a cage and substituting it for man’s soul being ‘trapped’ by his body was already a well-used comparison. The Romans did it, way back in the day. John Webster made a strikingly similar metaphor in his 1613 play The Duchess of Malfi: “Didst thou ever see a lark in a cage? Such is the soul in the body…” Hopkins’ updated version of Webster’s conceit (the central idea of a poem) is explicitly stated in line 12, which reads: Man’s spirit will be flesh-bound. However, it’s not the conceit which makes this poem so highly memorable – it’s the way Hopkins expresses and develops the poem’s central comparison into an extended metaphor, employing diction such as cage, mean house, prison, cell, barriers and bound to test the comparison in various ways. The sentiments of the poem are comparable to another he wrote called On a Skylark Singing in a Narrow Alley, which comments on the increasingly ‘imprisoning’ feel of modern society.

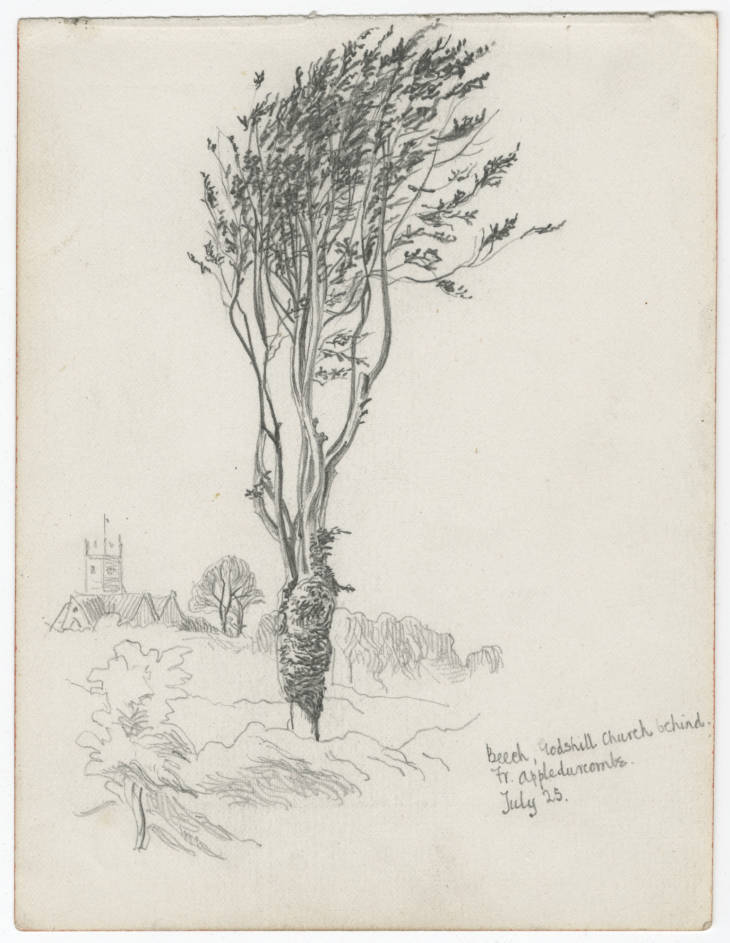

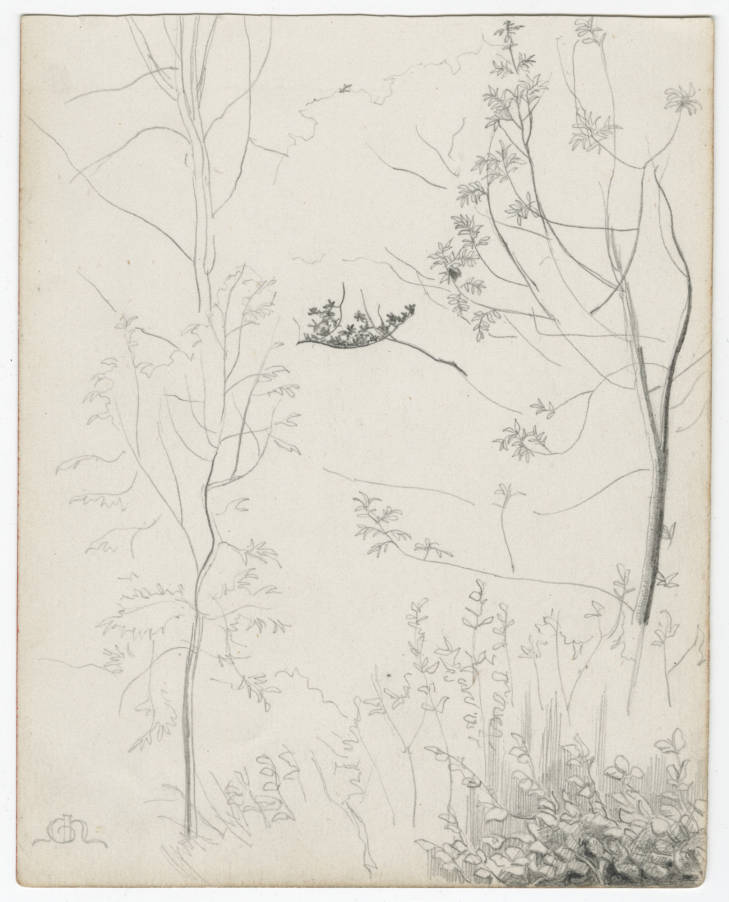

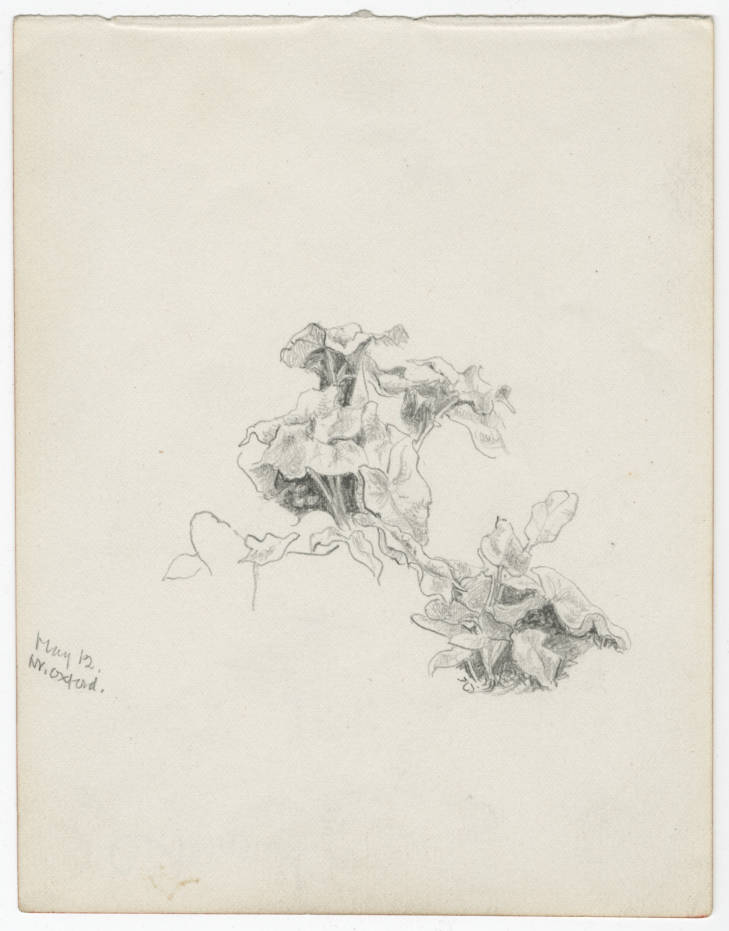

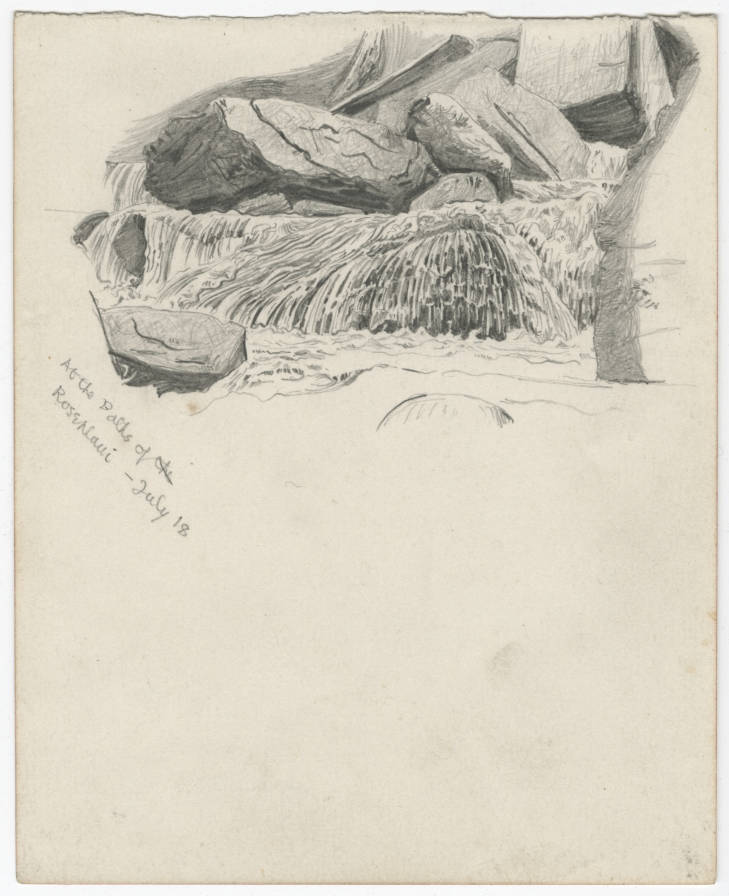

Beyond his religious instruction, Hopkins had enjoyed a highly creative and liberal upbringing, surrounded by music and art: his mother read Dickens to him; his aunt taught him to sketch fantastically detailed drawings (some of which you can see illustrating this post); two of his uncles were engravers, lithographers and painters; his brother, Lionel, became a professional illustrator. Hopkins himself wanted to become a painter before side-lining into writing. His artistic background is evident in the technique for which he is famously associated: his habit of using compound words to create original phrases and expressions; for example, dare-gale and bone-house. Hopkins coined the phrase ‘word-painting’ to describe what he was doing. In actual fact, he was drawing on an ancient Anglo-Saxon metaphor called a kenning, a kind of riddle that expresses a noun in terms of a metaphor. Bone-house is poached from Beowulf, an epic Anglo-Saxon poem. Hopkins employs bone-house as a straightforward metaphor for the body, the words suggesting that, far from being a frame or container for our living souls, the body is like a prison trapping the soul behind our cage-like ribs. The image would not be possible without the reference to bone, shaped like bars of an imaginary cage. Dare-gale is a metaphorical name for the skylark, but the word also expresses admiration when watching the bird ‘courageously’ wheeling and flying in the strong winds that buffeted the English countryside.

A talent for languages ran in Hopkins’ family (his uncle, Charles, went to Honolulu to be an Anglican minister and learned Hawaiian; his brother Lionel, the illustrator, moon-lighted as a minor celebrity in the world of Chinese translation). Gerard Hopkins must have shared their passions for exotic locales as well as aptitude for languages; in 1874 he moved to Wales and spent the next four years in tropical Rhyl learning Welsh. During this time, Hopkins grew fond of a particular feature of Welsh poetry called cynghanedd, translated by the Gerard Manley Hopkins Official Website (yes, really) as ‘consonant-chime’. This technique incorporates both alliteration and internal rhyme, an example of which can be seen in the second stanza:

Both sing sometímes the sweetest, sweetest spells,

…

Or wring their barriers in bursts of fear or rage.

You probably noticed the strong alliteration of sing/sometimes, sweetest/spells, barriers/bursts, but did you also hear that sing rhymes with wring? One effect of ‘consonant-chime’ is it creates euphony, allowing Hopkins to match style and content perfectly; the musicality of the poem mimics the skylark’s babble. Along with his prolific use of kennings, these aural touches were Hopkins’ trademarks, marking him out from other Victorian poets. Sadly, he wasn’t always appreciated in his own lifetime; it wasn’t until 30 years after his death when his good friend Robert Bridges first published many of his poems.

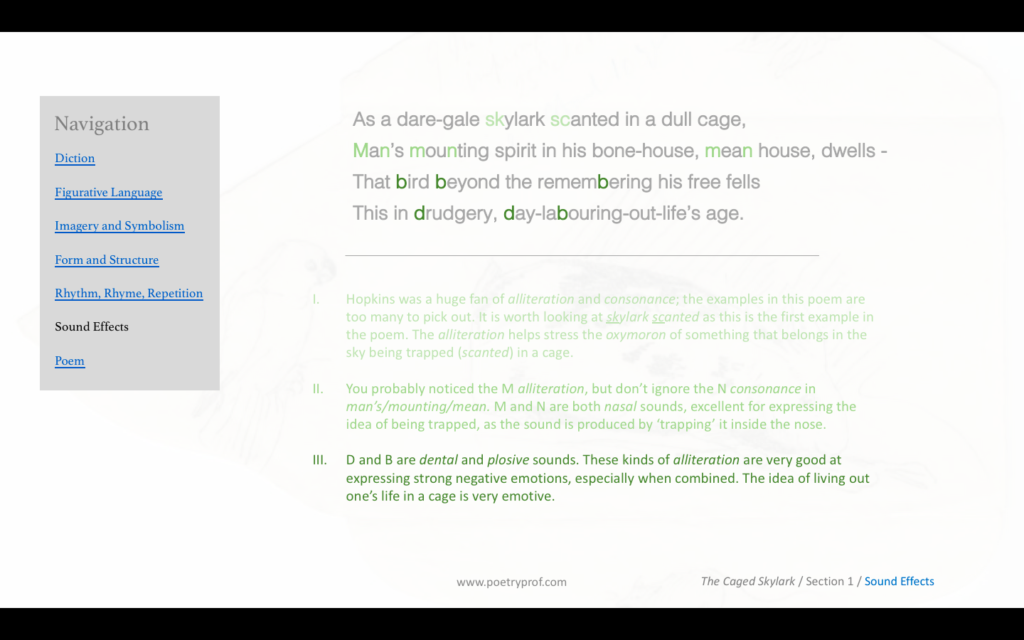

In fact, other traces of the ancient Anglo-Saxon language glimmer throughout The Caged Skylark. Alliteration was probably the defining feature of Anglo-Saxon poetry: all 3182 lines of Beowulf alliterated! Hopkins loved to arrange consonant sounds in deliberate patterns. For example:

This in drudgery, day-labouring-out life’s age.

Though aloft on turf or perch or poor low stage.

You can easily see alliteration in drudgery/day, labouring/life and perch/poor, and also consonance (alliteration of sounds anywhere in the words, not only at the beginning, is called consonance) where the ‘dg’ of drudgery matches with the ‘g’ in age. These sounds are hard and grating, conjuring the unpleasantness of life in a cage. Similarly, aloft on turf contains consonance: Hopkins was particularly fond of the back-to-back arrangement of sound (technically called chiasmus) which you can see here: F,T/T,F. In other examples the pattern might be alternating, as in flesh-bound when found at best: F,B,F,B. Such patterns reinforce the poem’s central duality; the comparison of a man’s soul trapped in his body as a bird is trapped in his cage. Other ‘pairings’ and juxtapositions include: the ABBA rhyme scheme of the first eight lines; frequent repetitions (e.g. bone-house, mean house or sweet-fowl, song fowl) the position of the bird either aloft or down; the opposition of wild nest and prison…you can undoubtedly find more.

The trapped-in-a-cage metaphor develops until it reaches an emotional climax:

Yet both droop deadly sómetimes in their cells

Or wring their barriers in bursts of fear or rage.

For me, this moment is full of existential grief and frustration; these lines seem aghast at the cruelty of a God who would consign his people to such wretchedness. As despair overtakes man and bird, they both rail against their entrapment, forcibly wringing the bars of their cages (barriers). The choice of the word wringing expresses both grief through association with wringing water from a cloth, i.e. tears, and violence through the phrase to wring your neck. The word has an additional onomatopoeic element that evokes the metallic sound of someone pounding on the bars of a cage, as one would ‘ring’ a bell. Hopkins’ favoured technique – alliteration– is evident in these lines, with plosive B and dental D combining to release those strong negative emotions. Even the rhythm is rigidly proscribed: did you notice how Hopkins marks the stress for us in the first syllable of sómetimes? This little detail practically forces you to read the lines metronomically, the strict iambic pentameter acting as a ‘prison’ for the words.

Of the two major types of sonnet, Hopkins choice of Petrarchan is apt. For starters, the rhyme scheme is tighter: ABBA, ABBA, CDCD. With only four sounds used to rhyme, instead of the seven sounds required by a Shakespearean sonnet, the ‘tightness’ of sound aptly connotes the reduced conditions of life in a cage. In a Petrarchan sonnet the volta occurs between the octave and the sestet. So, once the octave is complete and we understand that both man and bird are thoroughly miserable, Hopkins’ makes his ‘turn,’ giving us a look at life from the point of view of a free bird instead:

Not that the sweet-fowl, song-fowl, needs no rest –

Why, hear him, hear him babble and drop down to his nest,

But his own nest, wild nest, no prison.

In its natural state (i.e. uncaged) a bird is not confined and able to babble freely and drop down to sleep in his own wild nest. He is able to rest on his own terms and finds respite from the troubles of the world. Conversely, being a prisoner of his own body, man is essentially born into a state of bondage and can seek no earthly alternative. Therefore, this section of the poem spares no effort in pointing out differences rather than similarities, using negation to show what man lacks: not that the sweet -fowl, needs no rest, no prison. There are no more comparisons in these three lines; the poem simply exhorts you to hear him, hear him as he sings.

As a bird is happiest in his wild nest rather than a cage, so man will be happiest out of his cage. But – if his cage is his body then man can only be free out of his body. The logical conclusion of this train of thought is: man’s true state of grace can only be found after death. The most beautiful image in the sonnet is in the final tercet:

…meadow down is not distressed

For a rainbow footing it…

The poem finishes with a rainbow gently resting on the soft grass of a meadow. The rainbow represents man’s spirit, at peace and resplendent once he dies, and is also an allusion to a biblical story in which the rainbow is a symbol that God will keep his word to man. It’s as if, after all the frustration that Hopkins seemed to let out, he decides to trust that God knows what he’s doing after all. You can hear cynghanedd at play in the internal rhyme of meadow/rainbow and the alliteration of down/distressed and for/footing. There are further similarities between dow/down/bow and, coming in the next phrase, nor/not/for. Hopkins brings all his skill to bear on this image: it both looks and sounds beautiful. The idea that man is dragged down by his fleshly body while his spirit yearns towards heaven is expressed through the opposition of down and risen, while the rainbow is a splash of colour amongst the dull, mean drudgery of the world.

The last words of the poem, bones risen, allude to the idea of resurrection, life after death. Remembering Hopkins’ upbringing, and the idea that – at its heart – this poem is a kind of eulogy, the most obvious touchstone here is the story of Christ’s death and subsequent resurrection. It’s possible to see, in just these last two words, the way he works through his feelings about a god who would condemn his children to live confined and restricted by such limited bodies – because after our bodies expire, our souls will continue to live on in an afterlife. Look closely at the sounds of the last two words: you should see Hopkins’ favourite pattern – chiasmus– in the forward-and-back sounds of n-e-s – s-e-n. The shape of the sounds reminds us of: the up-and-down arcing of the rainbow; the uncaged bird free to drop down then jump up to its perch in the tree; the way the soul ascends to heaven after the imprisoning body dies. It’s a lovely way to end the poem.

A favourite motif of Hopkins was the singing bird. In 1877 alone he wrote 13 sonnets, of which The Caged Skylark is one. The motif would reoccur in his poem Spring of the same year. In another, The Windhover, he eulogised a small falcon he had seen in flight:

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, — the achieve of, the mastery of the thing

In yet another, The Sea and the Skylark, our friend the skylark – uncaged this time – reappears:

Left hand, off land, I hear the lark ascend,

His rash-fresh re-winded new-skeinèd score

In crisps of curl off wild winch whirl, and pour

And pelt music, till none’s to spill nor spend.

It’s easy to recognise the author of The Caged Skylark as the hand behind these lines, replete with alliteration, consonance, internal rhyme (stirred/bird) cynghanedd, (crisps of curl/wild winch whirl) and compound words.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Wreck of the Deutschland by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Not an obvious companion piece for today’s poem, as it’s subject is an 1875 shipwreck in which two-hundred people (including five nuns who feature in the poem) drowned. The event affected Hopkins so much it brought him out of retirement! Like The Caged Skylark, this poem wrestles with the dual nature of God: at once benevolent and good, while capable of tyranny and dread at the same time. It’s long, but a must-read for any would-be Hopkins devotees.

- Caged Bird by Maya Angelou

We’ve already discussed how the caged bird is a popular symbol in literature. Here it is again being used to powerfully suggest the evils of slavery.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Caged Skylark at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring Hopkins’ distinct style including cynghanned and kennings.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What did you think of Gerard Manley Hopkins poem? Do you like his dense poetic style? Did you find the comparison between man and caged bird apt or a bit cliched? What do you think of the final few lines? Why not leave a comment, ask a question, or start a discussion in the section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Hi loved this blog and wonder if you can help me.

Years ago I read a poem about a caged bird. The Bird flew up and down in frustration and when exhausted collapsed at the bottom of the cage. In this position of realised that the cage was open at the back and ‘he’s could have left anytime!I

It is such a powerful poem but I just can’t find it.I thought for a long time it was written by Sylvia Plath but I can’t go d it in any of her books.

Thank you in advance, for any clues you may be able to provide.

Kindest regards

Alison

Hi Alison,

That poem sounds so sad! It doesn’t ring any bells, but I’ll ask around and see what I can find out.

Hi Alison,

The best I can do for now is ‘Sympathy’ by Paul Laurence Dunbar. I’m sorry, it’s not the poem you described, but this poem was definitely an influence on Maya Angelou’s Caged Bird. I’ll keep looking though, and I have a couple of friends on the case as well. Fingers crossed.

I hate IGCSE poetry it confuses me so much but this helped alot thanks.

Hopkins never left the priesthood. He is buried in the Jesuit cemetery in Dublin. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5858594/gerard_manley-hopkins#view-photo=81985855

Hi Janine – what a great fact, thank you. I’d love to stop by and see the spot one day :o)