Elizabeth Jennings explores the poisonous power of paranoia in this cold-war parable

“It often seems, deceptively, like anyone could say what she does…”

Henry Oliver, Instagram is the Future of Poetry, 2021

Elizabeth Jennings lived through the turmoil of mid-twentieth century Britain. Born in Lincolnshire in 1926, she came into her adulthood during World War Two and lived in Oxford for most of her life. A writer during the 1960s and 1970s, her time was marked by material and economic boom; yet this was also a period of political tension fuelled by fears of communism and a ‘cold war’ with the Soviet Union. This dichotomy manifested itself in art, literature, and the media: the 1960s saw the rise of Beatlemania alongside the paranoia-boosted popularity of spy-thriller writers such as Ian Fleming, John Le Carre, and Frederick Forsyth. Feminist and civil rights movements gained traction, yet the proliferation of nuclear weapons created just as much anti-war protest as there was free speech and free love. Immigration to the UK boomed as people came from the Caribbean, Indian subcontinent, and elsewhere to find work (which was plentiful) and so anti-immigrant xenophobia snaked ugly roots through England’s fertile soil. It’s against this complicated backdrop that Jennings wrote The Enemies, a poem with a provocative title, that asks us to ponder who the real ‘enemies’ are: people from faraway lands who migrate in search of jobs, stability, and safety? Or the brooding suspicions in the minds of people who object to those who speak a different language? Jennings explores the powerful effect of paranoia and mistrust, showing how these reactions can erode the bonds of a community, and worries that these feelings might be universal when ignorance replaces reality with rumour.

Last night they came across the river and

Entered the city. Women were awake

With lights and food. They entertained the band,

Not asking what the men had come to take

Or what strange tongue they spoke

Or why they came suddenly through the land.

Now in the morning all the town is filled

With stories of the swift and dark invasion;

The women say that not one stranger told

A reason for his coming. The intrusion

Was not for devastation:

Peace is apparent still on hearth and field.

Yet all the city is a haunted place.

Man meeting man speaks cautiously. Old friends

Close up the candid looks upon their face.

There is no warmth in hands accepting hands;

Each ponders, ‘Better hide myself in case

Those strangers have set up their homes in minds

I used to walk in. Better draw the blinds

Even if the strangers haunt in my own house.’

Reading this poem reminded me of being terrified by The Invasion of the Body Snatchers when I was young. In this film, the inhabitants of a small American town are gradually replaced by copies of themselves as the prelude to an alien invasion of Earth. The tension in the movie comes from characters not knowing if their friends and family are still themselves, or if they have been turned into ‘pod people’. Originally made in 1956 (I’m not that old, so I watched the remake when it was on television late one night) the film used alien invasion as a metaphor for communism undermining American society; infiltrators and spies spread insidious political ideas that turned ordinary citizens into enemies of the state. Exactly the same fear pervades the city of Jennings’ poem. Who are the mysterious visitors who disturb the equilibrium of the town? Jennings sketches them in barest outline, using the pronoun they four times in the first stanza alone (although be careful to spot one instance refers to the women of the town, not the mysterious visitors). They travel in a band, which could seem threatening, and are later called strangers which sets them up as unknown and unknowable outsiders. Yet they commit no evil actions; by the townsfolk’s own admission, their reason for being here is not for devastation. At the end of the day, the simple fact that they are outsiders and have not proactively assuaged the fears of the townspeople is enough to get everyone talking… and imaginations start to conjure up worst-case scenarios of cultural and ideological infiltration.

Beyond the Body Snatchers comparison, the poem can be read like a twisted fairy tale as well. The setting has a timeless feel, a nameless city bordered by a river, the main action unfolding in a compressed time-space of one night and the next morning. Some diction is allegorical: Jennings uses the slightly archaic phrase strange tongue instead of ‘foreign language’, the strangers are never identified, either by name or nationality, nor is the city and river. Other words like haunted, band (meaning group of men), land (instead of ‘country’) are drawn from stories and fables. This invasion (that’s not really an invasion) could be happening anywhere and the townspeople could represent anyone. In the manner of a storybook narrator, the poem’s speaker keeps a certain distance from the action. Presumably she’s one of the townspeople, and she seems semi-aware of the workings of paranoia on the minds of her fellow citizens, but she doesn’t judge overtly. She simply reports what happens and allows us readers to come to our own conclusions. Actually, in verse one her tone is pretty much, well… toneless! She flatly recounts how they came across the river and entered the city in diction that is almost totally banal, to the extent where a word as plain as came is repeated twice in this form and once more as come. Entered is equally neutral. It’s later, when she begins to use more figurative language, that we can appreciate how suspicion twists the mindset of the townspeople and hear for ourselves how rapidly their attitudes towards their guests deteriorated.

The sense of ‘us-vs-them’ is intensified through a gender opposition; the outsiders are all men whereas the townspeople who welcome them are women. There is no mention of women amongst the visitors, which is perhaps one reason they might seem vaguely threatening. While perhaps not a tactic that would be as politically correct today, creating a gender imbalance between the vulnerability of women and a large group of strange men, along with the assumption that they want to take something, is a significant contributor to the latent sense of threat when the outsiders first arrive. Notably, later in the poem it is the men of the town who close up to each other, letting suspicion shut down their mutual humanity until all that remains between former friends are cold, clinical, and impersonal interactions, memorably sketched in the line: no warmth in hands accepting hands. There seems to be an implication that women tend towards warmth and empathy in situations like this, whereas men tend to react with hostility, a dichotomy that plays into certain old-fashioned stereotypes about men and women’s essential natures. Does this date the poem poorly? (I’d be interested to hear your reaction to this element of the poem in the comments, should you have any opinion.) Nevertheless, the initial reaction of the women is genuine as they lay out the welcome mat with lights and food and entertainment. Perhaps this arrival was not entirely unexpected: the women were awake and seemed prepared to receive these strangers after all.

The townspeople’s conflict with the outsiders actually rests on a single action – or rather inaction. Despite their initial generosity in providing for the new arrivals, not one person tries to talk to the outsiders and ask who they are, where they are from, or why they have come. Of course, the language barrier might be a real problem, but it shouldn’t be impassible, and nobody makes any effort to overcome this obstacle. It’s failure to communicate that lets ignorance prevail, causing a vacuum of knowledge that rumour is ready and eager to fill. Dishearteningly soon, the attitude of the city’s citizens morphs into suspicion of the outsiders: but even before the open hostility of verse two, we can sense doubt creeping in to the minds of the townspeople. At the end of the opening verse, repetition of the word or (repetition at the beginning of lines of poetry is called anaphora) creates the impression of panicky thoughts flicking through people’s minds. A sequence of three question words in lines four to six (what… what… why) intimate that these unanswered concerns would sway public opinion for the worse. As the city-dwellers never pluck up the courage to simply ask, what start out as plausible concerns begets suspicion – soon enough, paranoia, which begins as only a thin skin over the surface of the poem, begins to curdle and thicken as the arrival of the outsiders is reframed as an invasion.

Unavoidably, we readers are drawn into the mystery and implicated alongside the townspeople; we too are touched with the doubt darkening the citizens’ minds. Jennings uses enjambment in a way that creates moments of uncertainty, so we are never quite sure how a line is going to end, or what the visitors are going to do next. This is most apparent at the end of line one: Last night they came across the river and… and what? For a split second, before our eyes can scan to the start of the next line and read entered the city, our imaginations had a chance to complete the line with any number of nefarious possibilities. This happens frequently: when the second verse begins with the line Now in the morning all the town is filled… your own mind might be tempted to fill the town with strangers up to all kinds of mischief before you can scan forward and see the town is filled with stories and rumour only.

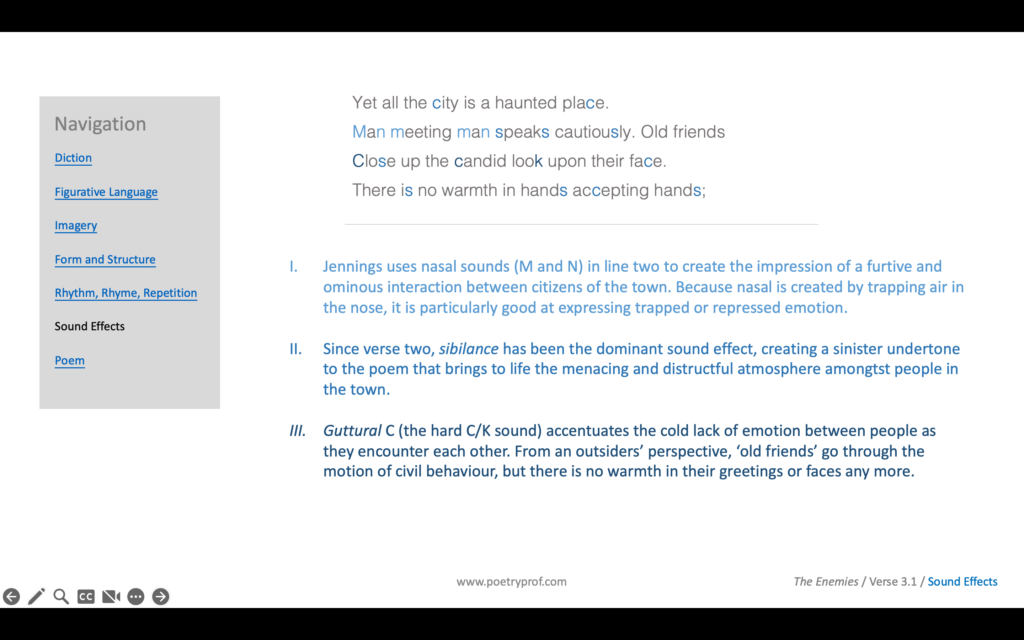

The palpable feeling of dread spreading insidiously through the tight-knit community is evoked through sound as much as any other method. Sibilance is Jennings’ most important ally in this regard, and she uses the faint, whispery S to twist the atmosphere of the city (and the poem) into something sinister. When the women spread out that warm welcome, Jennings arranges a sequence of rich W sounds to bring out the generous spirit of the greeting: women were awake with lights and food. However, as the worm of suspicion begins to gnaw, a thread of sibilance is woven into the poem: not asking what strange tongue they spoke… From this moment on, through the symbolic association with the snake, hissing sibilance conveys feelings connected to manipulation, secrecy, underhandedness, and distrust. The undertone intensifies in lines such as stories of the swift and dark invasion and briefly takes on a harsher Z sound in the line: old friends close up. You might also notice the hard C/K sound that’s quite prominent in this line (close up the candid looks). Called guttural, this sound carries hard, aggressive connotations. First associated with the mysterious outsiders when they came across the river, here the unpleasant quality of sound is transferred to the town citizens, stripping their interactions of any emotional depth, and making them seem cold, clinical, unfeeling. This transference also seems to shift the blame for what happens to the town away from the visitors and onto the residents themselves.

The second verse brings morning and it’s under the revealing light of day where it’s easiest to see the shifting of attitudes which Jennings wants to interrogate. With the spreading of tall tales comes a corrupting of people’s thoughts and a worsening in the quality of their characters. This transformation is presented in the language of the townspeople and the way they frame the outsiders’ arrival. A quick compare-and-contrast between the diction of verses one and two shows how reality bends when fearful speculation runs riot. What began as a simple ‘coming’ of people into town or ‘crossing’ of the river is now a swift and dark invasion; their being in the town is labelled an intrusion. Dark is a word with layers, suggesting the assumed bad intentions of the outsiders and the ‘dark’ direction of the townspeople’s thoughts both. (Might this also be a clue as to the colour of the visitors’ skin?) Fears of devastation are wildly exaggerated; as the speaker admits in the last line of verse two, peace is apparent still. The word apparent is used with intention: there is no actual evidence of any crime, destruction exists only in the increasingly unhinged imaginations of the townspeople. In this context, words such as invasion and intrusion belong to a category of metaphor called dysphemism. This technique is used when people want to make things appear worse than may have been true in reality. Politicians are particularly accomplished at employing dysphemism (and euphemism) for rhetorical effect and, sadly, the type of cognitive dissonance on display in The Enemies is not unusual. Any number of case studies show that rhetoric born of fear is often several steps removed from reality when it comes to the impact of immigrant people on the communities they join. In recent UK history, right-wing politicians frequently rouse anti-immigrant sentiments in voters by using exactly this kind of language; ‘invasion’, ‘swarm’, ‘plague’, and so on.

And once again, it’s hard for the reader to remain entirely innocent as Jennings keeps manipulating us into feeling a little off-balance ourselves. For example, the poem is mostly written in iambic pentameter, a very familiar meter for readers of English poetry, with its predictable ‘de-dum, de-dum’ rhythm and five stressed beats to every line. That is, until we reach the truncated fifth line of each verse, which is shortened to only three beats (technically, these shorter lines are called trimeters). We are thrown off our guard when the familiar rhythm we’ve come to expect doesn’t play out like we thought. As well, Jennings crafts her rhyme scheme into a fairly unusual ABABBA pattern, so the last two lines invert the ABAB rhythm, adding to our momentary discombobulation. When employing rhyme, Jennings frequently mixes full-rhymes with half-rhymes, which occur when either the vowel or consonant component of rhyming words are the same, but not both. Take/spoke, filled/told/field, intrusion/devastation, friends/hands, and case/house are all combinations which create an uncomfortable tension, as if things are not quite right between the words, just as things are not quite right in the minds of the city folk. Lastly, Jennings subverts on the macro level as well. She writes her poem using elements of a Petrarchan sonnet, a form in which the first section is written in six lines (sestet) and the second section has eight lines (octave). It’s just there’s a whole extra section to contend with here, two sestets where there should be only one! All these formal elements combine to help feelings of paranoia creep off the page and into the mind of the reader – like it or not. Through involving us emotionally, even in a very limited way, Jennings conveys the subtle idea that this kind of reaction may be more common than we might like to admit. After all, if we feel a touch of distrust at such a distance from the action, what might we feel should this be happening in our own homes and we were more closely involved? Perhaps this poem chimes with your experiences at school, work, or elsewhere. Have you ever been a member of a balanced group, only to feel disrupted by the arrival of a new member? Whether or not the person was good or bad, whether they brought positive vibes or were a negative influence, the equilibrium is disrupted, and the past dynamic can’t be recaptured once it’s gone. You may even have been that new member, joining a team or class at the midpoint of a term or season, and finding it hard to fit in despite your best efforts. Fear of losing the intimacy of an established community, or of knowing who your neighbours are and that they think in similar ideological terms to you, may cause pre-emptive resentment that is amplified in the cold war context of this poem.

All this comes to a head in the third and final verse where the city is unrecognisably changed. Infecting the town lightning-fast, paranoia has turned old friend against friend and neighbour against neighbour. The speaker continues to report: Man meeting man speaks cautiously and There is no warmth in hands accepting hands. Her flat, dispassionate tone and the way she so precisely, almost mechanically, arranges two sets of parallel repetitions (man meeting man… hands accepting hands) strip these interactions of any warmth and emotion. It’s as if people are going through the motions of civility, without any iota of trust and neighbourly caring that characterises real friendship. The arc of the poem, from warmth to cold caution, from openness to closed up suspicion, from the sharing of light and food to squatting alone in a darkened room, finds its shape in these last few lines. Jennings uses alliteration to imply the spiritual emptiness of the town in the ironic phrase man meeting man; nasal M/N is created by trapping air in the nose so the sense of holding everything back or repressing all feeling is conveyed.

Whether or not we should have any sympathy for the townspeople is up for discussion, and I’d be interested again to read your thoughts in the comments. I can see how the arrival of a large group of strange men so suddenly in the night might raise a few hackles. It can be intimidating when faced with ‘otherness’, especially when there’s a language barrier, and the poem raises the uncomfortable possibility that it might be natural to retreat into defensive silence rather than risk opening oneself to harm. The use of words such as hearth, homes, and house suggest an intimate fear that strangers might penetrate into the most private of spaces should people let their guard down. On the other hand, Jennings shows how separation of people into ‘us-and-them’ categories is in itself an act of self-harm, as people whose first instinct was to offer kindness and succour are then poisoned by paranoia. The newcomers didn’t do anything wrong; their unexpected newness, maleness, and difficulty communicating was enough to throw the town off-kilter and into a death-spiral of distrust. Ultimately, hiding away doesn’t solve anything; in the metaphor the strangers haunt in my own house, rampant paranoia implicates people’s own family members whose thoughts they now begin to suspect.

Cities are made of people, not just houses and buildings, so a closing of one’s home becomes a closing of oneself to others, whether they be total strangers or close family. Given an insight into the thoughts of the townsfolk by our omniscient narrator, we see them all thinking the same thing: ‘Better hide myself in case those strangers have set up their homes in minds I used to walk in. Better draw the blinds…’ Anaphora (Better… better…) is put to work once again to mimic the frantic thoughts of people persuading themselves that their irrational courses of action are the only ones available. The symbolic equivalence of a person’s home with a person’s self is formed by the minds/blinds rhyme, so a drawing down of the shutters becomes an inability to think of alternative outcomes, a metaphorical blindness where dark thoughts and specious rumours are given more credence than reality. Once adopted, the habit of suspicion is hard to drop. Jennings leaves us with an image of a community fractured beyond repair as everyone hunkers down, doors barred, lights out. In seeking to protect themselves from harmless strangers, the people of the town have become strangers unto themselves.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- One Flesh by Elizabeth Jennings

Always interested in exploring and exposing people’s foibles, this is one of Jennings’ most famous poems. Loosely based on her own parents, the poem describes two ageing lovers who now sleep in separate beds. Their passion may have cooled, but they are connected by ties of love stronger than physical desire.

Duns Scotus’s Oxford by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Jennings’ favourite poet was Gerard Manley Hopkins; so, as she went to Oxford University, and subsequently lived in Oxford for many years, here is Hopkins’ poem about the city of Oxford.

- The Immigrants’ Song by Tishani Doshi

A persuasive reading of Jennings’ poem is that the men who come to the city are migrants seeking work, stability and a new home. The way they behave seems to bear this out; they cause no trouble, yet are mistrusted when people accuse them of being ‘invaders’. Doshi’s poem turns the tables and writes from the perspective of one who is descended from immigrants.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Enemies at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining rhyme and half-rhyme.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Elizabeth Jennings’ poem? What did you make of the clear divide between men and women? Do you have any sympathy with the townspeople’s reactions? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Six line stanza is usually a sestet, not a tercet…

Oh – good spot! Thank you, I’ve corrected my mistake in the blog now.