Sarah Jackson makes an unexpected connection in this elusive poem about travel and change.

“Jackson’s poems have a compelling strangeness, uncomfortably intimate and elusive at the same time.”

Nicholas Royle, writing about Jackson’s debut collection.

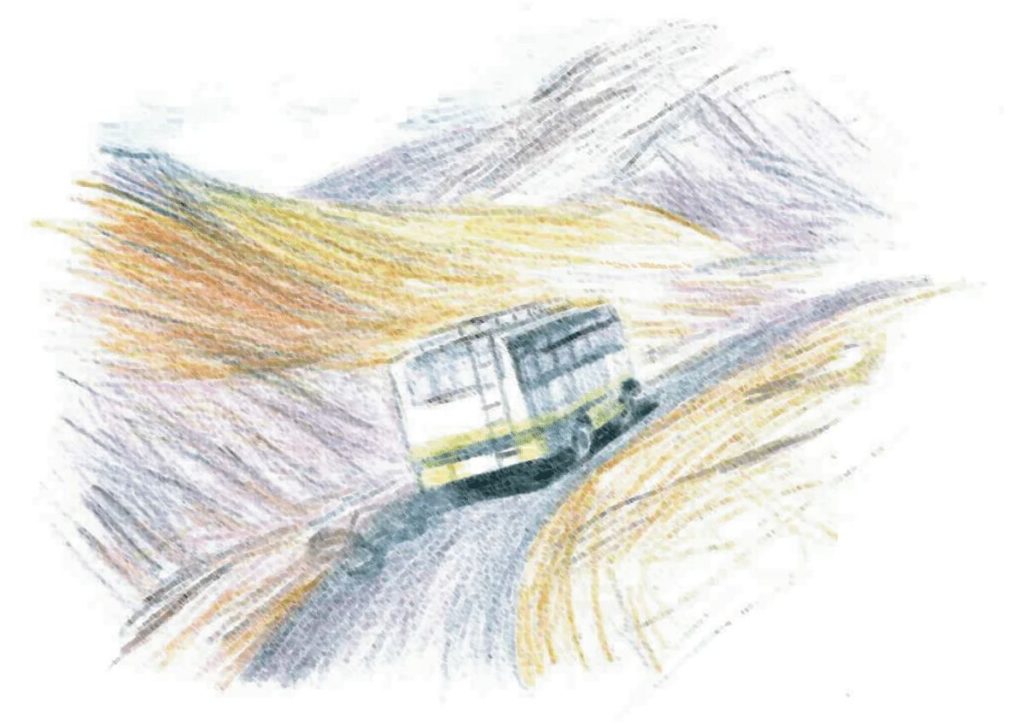

Today’s poem is set in Northern India where the Himalayan mountains press up against the Tibetan plateau forming a mighty range of rocky peaks. This area is called Spiti, a remote and adventurous destination, and it seems like Jackson’s writing from her own travel experiences (the poem is written in the past tense and in the first person; it reads like a reflection or recalled memory from her past). Jackson has form writing about the topics of travel and personal change or re-invention: one of her poetry collections is called In Transit: Poems of Travel and she won the Seamus Heaney Center Prize for a book of poems about transformation from youth to old age. In The Instant of My Death, she writes ambiguously about a long-distance bus journey high up into the mountains. Exhausted by the trip, she’s on the verge of letting herself fall asleep when an unexpected encounter jerks her vividly awake. While occupying only a few brief moments in the endless hours of the drive, her communion with a local boy reminds her, and us, that no matter how far off the beaten track we may go, it’s the tiny, spontaneous moments of connection with other people that stick in the memory and make exploring faraway places worthwhile:

The bus was crammed and the fat man rubbed against my leg like a damp cat while you read The Jataka Tales three rows from the back and we all stumbled on; wheels and hours grinding, tripping as Spiti rose up around us, sky propped open by its peaks. I traced the rockline on the window with my finger, counted cows and gompas, felt my eyes glaze over until we reached Gramphoo. There, where the road divided, I saw a thin boy in red flannel squat between two dhabas; a black-eyed bean, slipped in between two crags, he was so small that I almost missed him, until he turned, gap-toothed, and shot me with a toy gun. And a piece of me stopped then, though the bus moved on, and the fat man cracked open an apple with his thumb.

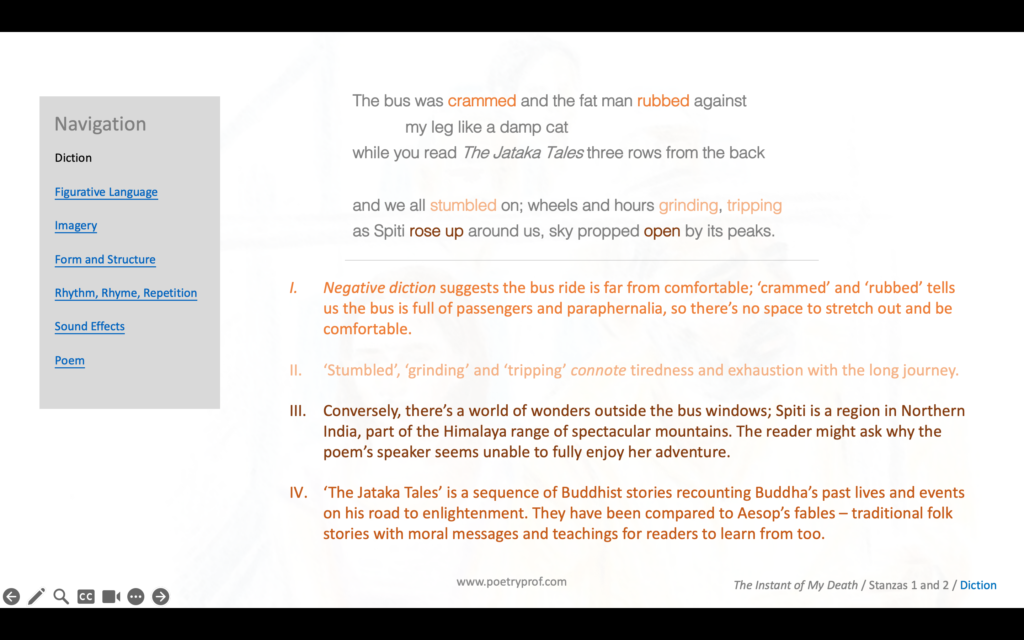

The poem opens partway through a long drive into the mountains. The bus is crammed full of passengers, a mix of travelers and local people going from village to village, town to town. In such a remote place, public transport services aren’t frequent, and no doubt local inhabitants are keen to take advantage of a bus that might only pass by once a day, if that. Jackson is travelling with a companion who’s sitting separately three rows from the back. Seemingly unbothered by the uncomfortable conditions inside the bus, he or she is absorbed in a book called The Jataka Tales, a collection of Buddhist stories chronicling Buddha’s past lives and his road to enlightenment. The act of reading these stories symbolizes the speaker’s traveling companion’s curiosity for and immersion in the journey and, through allusion (if you recognise the title of the book, you will know the themes of the stories inside) suggests ‘enlightenment’ or self-discovery is a possible reason to go traveling in the first place.

While her companion is engrossed, the same cannot be said of Jackson’s speaker who’s finding the journey a bit of a chore. Diction betrays her negative mindset; the word crammed tells us the bus is unpleasantly full, and the way a fat man rubbed against my leg is bothering her. She describes this intrusion into her personal space through the simile like a damp cat, making the unwanted physical contact seem clammy and persistent, in the way a cat will keep nuzzling you to be petted (although I’m sure it’s unintended on the part of her seatmate). Stumbled, grinding and tripping suggest exhaustion as wheels and hours spin by endlessly, taking them higher and higher into the mountain range. Although there must be much pleasure in traveling through such an incredible place (images of the Spiti mountains that rose up around us imply an epic journey into a majestic landscape under a grand open sky) right now it’s just too challenging to fully enjoy and either she’s tired by the journey or tired of the journey.

The bus functions as a capsule insulating her from the full impact of the outside world; airless and stifling, she’s on the verge of nodding off. Outside, the landscape has a stark, lunar beauty – but there’s only so many sheep, cows and gompas (small temples, more like shrines really) that she can look at and still feel any frisson of amazement. In fact, the way she traced the rockline on the window with my finger betrays a little boredom, as if the scene is more like the background for her own daydreaming than something she’s really looking at (by contrast, her travelling companion is immersed in the exotic stories of this region, a comparison that draws out her lack of engagement nicely). When she resorts to counting cows for some kind of distraction, it reminds me of the way a person might count sheep to help them fall asleep. Finally, she admits her lethargy and says she felt my eyes glaze over. Her exhaustion is somewhat mirrored in the environment that’s grinding past outside the bus windows. Through pathetic fallacy, a type of metaphor whereby human emotions are transposed onto the natural world, the sky is described as propped open by its peaks, as if the eyelids of the world are drooping with fatigue (although, conversely, strong P alliteration in this line conveys something of the grandeur of her epic surroundings, if only she can focus her attention a little better). Despite the wheels and hours grinding away, the feeling persists that they are stuck going nowhere; when Spiti finally rose up around us the active verb is attached to the mountains themselves, so from her tired perspective it feels like it’s the landscape that’s moving around her stationary viewpoint. Over the first few lines and verses, there’s a niggling feeling – faint, but persistent – that she’s somehow reluctant or unable to fully open herself to the possibilities of her adventure.

All the while Jackson’s poetry conveys something of the grandeur of the surroundings that she experiences through the half-fug of sleep, almost as if she’s in a dream. She writes in an unusual stanzaic form of two-line stanzas and more often than not she uses enjambment so one line continues into the next, like the bus cruising on without even the briefest of toilet-breaks. She even enjambs between verses, so each couplet becomes a snapshot of a longer experience, with the same mountains spiralling up around her each time her eyes droop closed and open again. She writes in long, long sentences extended by conjunctions (and, while, and again, and as spin out the first sentence) and an innocuous semi-colon (and we all stumbled on; wheels and hours grinding) stretches the sentence even further, like it’s taking the bus an eternity to get to any kind of destination. Her internal struggle is evoked through alliteration and consonance, techniques that repeat letters at the beginning of and inside words respectively. Scattered around the first half of the poem like boulders on the sparse hillsides are frequent hard consonant sounds that suggest the going is not entirely smooth. At one point, alliteration seems to measure each second dragging interminably as time slows to a crawl (counting cows and gompas…). In several lines, plosive sounds (made with the letters B and P) dentals (D and T) and gutturals (made with G, hard C and K) suggest hardship and difficulty – yet also contain the rugged quality of rock formations, crags and jagged, flinty peaks. As the jouney is hard, the spectacular landscape is too hard and unforgiving. When these sounds are combined in lines such as The bus was crammed… rubbed against my leg like a fat cat, and Spiti rose up… sky propped open, the auditory effects, both positive and negative, are multiplied.

Finally, though, the bus reaches somewhere meaningful; namely Gramphoo, a mountain waystation for travelers to replenish themselves. The speaker mentions dhabas, which are roadside cooking stalls, complete with charcoal stoves and various ingredients that can be quickly whipped up into delicious curries for hungry passengers. While Jackson is sorely in need of replenishment – perhaps of a more spiritual or attitudinal kind – our bus doesn’t stop and whizzes past the lines of cooks, hawkers, and their hangers-on. The change in scenery does provide a distraction though, and something catches her eye: a little local boy who pops out from between two rocky crags as if by magic. His appearance transforms her journey, and the brief-but-powerful interaction between them has a significant impact on her alertness. Before she was nonchalantly tracing the outline of mountain scenery on the window, daydreaming, and letting her eyes glaze over; by contrast, this encounter is vividly burned into her memory. The boy’s playful and spontaneous interaction with her (he shot me with a toy gun) forms a momentary connection that strikes the speaker physically – he ‘shoots’ her awake with a start – and also with the force of epiphany, a sudden realisation where the essence of something is revealed. The action of ‘shooting’ is therefore both literal and figurative: the violent connotations of shot remind us that the road to ‘enlightenment’ can be long and difficult, and may involve hardship and even pain. I saw a thin boy and I almost missed him suggests Jackson knows that, on the verge of being overpowered by tiredness, the moment could easily have passed her by. There’s also a nice little rebuke to her companion here; head buried in The Jataka Tales, he would have missed this opportunity for connection with another human being. Perhaps Jackson’s suggesting enlightenment won’t be found in the dry pages of a book but through real-life experience and being prepared to open one’s eyes to one’s surroundings.

While it might be a stretch to say the poem is all about Jackson’s search for ‘enlightenment’, there’s definitely a sense that she was looking for direction, some kind of course-correction in her prevailing outlook, perhaps. For here, where the road divided, is the turning point of the poem; a ‘fork in the road’ that presents a symbolic choice. Tired of the journey, one road will take her back down the mountain, returning her to a recognisable and comfortable world. The other will climb higher, leading to new discoveries – but she’ll need to find a way to open herself to the possibility of adventure, or sharpen her perceptive faculties, things she’s found hard to achieve before now. This moment is signposted (some might liken this to foreshadowing in prose) throughout the poem by the significance of the number ‘two’: the divided road splits in two; two crags; two dhabas; each verse is composed of exactly two lines – all symbolically mirroring the moment when a piece of me stopped, and the traveler metaphorically divides in two as well. At this instant, her ‘past’ self is left behind as if it fell by the roadside, and her ‘new’ self emerges, reinvigorated and ready to embrace her adventure more fully. I think the title of the poem, The Instant of My Death, is revealed to be a clever piece of misdirection; ironically, she seems to become more alive after he shoots her.

In truth, the poem’s ambiguity makes it hard to put our fingers on precisely what changes after a piece of me stopped. While I’m reluctant to blindly guess why, I’m hazarding that she was a bit lonely and felt isolated way up in the mountains. After all, her friend was off in his own imaginary world so perhaps she was feeling ignored or upset at having to share a seat with a stranger. With nothing else to do, she lets the repetitive scenery slide across her gaze, and finds herself on the verge of nodding off. Like a shot of adrenaline to the heart, the boy’s spontaneity sparks her awake. The details she provides (thin, red flannel, gap-toothed, small, the way he squats by the cook-stands) are more vividly drawn than the hazily traced rocklines of the Spiti mountain range and he certainly stands out memorably. While the colour contrast is not explicitly made, his bright red flannel shirt exposes him against the drabness of the background scenery, signalling some kind of symbolic importance. The metaphor black-eyed bean, intensified by alliteration, gives him a dark and mysterious allure as well as emphasises how small he is; it’s interesting that the massive mountains had less impact on her than this single soul. More alliteration dramatizes the moment of connection between them, turned, gap-toothed, shot and toy gun feature strong G and T sounds that follow a period of relative quiet; listen to how slipped in… he was so small that I almost missed him uses sibilance and nasal M, N to lull us into a hazy, dreamlike state… before the staccato sounds of the toy gun crack in your ear like a shot! If you’ve ever dozed in the back of a car only to be suddenly jolted awake, you’ll be able to relate to the abruptness of this feeling. However you want to describe his transformative role, the boy is significant in energising and fortifying her for the journey ahead.

Therefore, while the final lines of the poem seem to take us back to the beginning (this is called loop composition) as the bus moved on and we are reacquainted with the fat man who still takes up more than his fair share of the seat, actually we get the impression that things have changed. For starters, she doesn’t complain about his pressing against her anymore. Instead, she describes the way he cracked an apple open with his thumb, the word open being an example of how diction – as well as her outlook – has altered. In another positive change, cracked has replaced crammed, the vivid onomatopoeia conveying something of how her perceptions have sharpened and her senses become more acute (an impression supported by whip-sharp sounds such as hard CK and plosive P in apple open). The opening of the apple, splitting it into two, certainly associates with the opening of the speaker’s perceptive abilities, and the way she feels a part of her has been left behind at the site of her epiphany. While literary and cultural associations of the apple are myriad, several symbolic meanings carry connotations of ‘rebirth’ that fit with this reading of the poem. To mention a few examples, in China apples symbolise Spring, youth and new beginnings; in Greece they are symbolically associated with new beginnings through fertility; in Judaism apples are eaten at New Year, again symbolising a new beginning; and in Christianity, while many believe the forbidden fruit devoured by Adam and Eve was an apple, it is not explicitly stated so in the Bible. Instead, upon his resurrection Jesus Christ is often depicted holding an apple in his hand, and in these cases it carries symbolic associations of rebirth, redemption and renewal.

Whatever interpretation you’d like to go with, gone is the clammy, claustrophobic impression of the opening verse; in its place we are left with a crisp, sharp image that hints at the promise of a new beginning, new adventures just beyond the next bend in the road.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Host by Sarah Jackson

Strange and uncanny, a little like The Instant of My Death, this poem comes from Jackson’s award-winning debut collection Pelt. The speaker is in a deserted hotel somewhere in Bulgaria with an unseen companion; the sounds and smells of the ocean carried on the wind surround her and begin to work their strange, sensuous magic.

- The House Was Quiet and The World Was Calm by Wallace Stevens

In this interview, Sarah Jackson cites Wallace Stevens as one of her poetic influences, so here’s a poem by the great master himself. I picked this poem for you because it is written in two-line stanzas, just like The Instant of My Death.

- Travel by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Millay’s speaker hears trains rattling past day and night – and imagines herself leaping aboard, heading who knows where. The destination is not important; as she says, “There isn’t a train I wouldn’t take, no matter where it’s going.”

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Instant of My Death at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining enjambment and caesura.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Sarah Jackson’s poem? How did you interpret the ambiguous images of the journey? What do you think changes inside her after her encounter with the small boy? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Here is a brief description of the last 2-3 stanzas. Not everything, some taken from this blog but yeah, some of my thoughts on this:

The boy makes her feel alive again after he shoots her with a toy gun.

Her old self dies; “a piece of [her]” dies and falls to the roadside, as she expresses in the phrase “a piece of me stopped then, though the bus moved on,”. She has moved on, along with the bus, from her old self.

Near to the end of the poem, she uses loop composition and refers back to the ‘fat man’ that was first introduced in the first stanza of the poem. But, instead of being annoyed with him, as she was in the beginning, she describes how he “cracked open an apple with his thumb”. The use of the verb “cracked” suggests that she is entering a new form or phase of her life. The use of the noun “apple” has connotations of new life, especially in religious contexts such as Judaism, where apples are eaten at the new year to represent a new beginning and the ‘fat man’ is opening this up.

There is also a subtle reiteration of the number two. For example, most of these stanzas (except the first and last, due to enjambment) are couplets, consisting of two lines. In addition, Jackson skillfully incorporates this particular number in how ‘the road divided’ into two and describes how the boy ‘squat between two dhabas’ and she again uses this number in how this same boy ‘slipped in between two crags’. She also describes the boy as ‘gap-toothed’, which could mean the boy’s own teeth set has split into two. In the final stanza, Jackson implies that she herself has also metaphorically split into two, and some of her is metaphorically left on the roadside. In addition, the ‘fat man cracked open an apple’ so the apple has also split in two.