Alfred Lord Tennyson conjures a spectacular and sympathetic vision of a mythical creature.

“Next to the bible, In Memoriam is my comfort”

Queen Victoria (In Memoriam is a work by Tennyson)

In Tennyson’s time, Britain was a naval power and her ships sailed to the four corners of the earth. Exploration of the New Worlds – the Americas, the Far East, Africa and India – opened up horizons new and possibilities strange and wondrous. Upon their return, sailors brought with them not only goods, wealth and plunder but also stories – real and imagined – of the incredible people and creatures that inhabited those faraway lands and seas. Of all these strange and bizarre denizens, the Kraken was one of the most fearful…

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides; above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages, and will lie

Battening upon huge sea worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

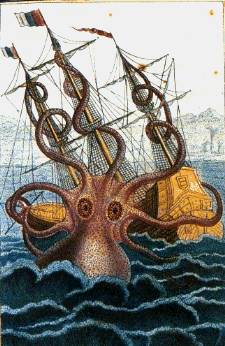

In Nordic folklore, the Kraken was said to lurk in the icy-deep oceans between Norway and Iceland, attacking vessels with its giant arms or causing huge whirlpools which dragged ships to their ruin. Its place in the popular culture of the time was strong thanks to these sea-tales, drawings like Pierre Denys de Montfort’s fantastical 1802 depiction of a Pulpe Colossal (Giant Squid), and through a growing literature of fantastic voyages: Jules Verne’s 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea would feature a sequence in which Kraken attack. In 1814 Sir Walter Scott wrote these lines about the fearful beast and I have read that these may have been one of Tennyson’s sources when composing his sonnet:

“In respect that your grace has commissioned a Kraken,

You will please be informed that they are seldom taken;

It is January two years, the Zetland folks say,

Since they saw the last Kraken in Scalloway bay;

He lay in the offing a fortnight or more,

But the devil a Zetlander put from the shore,

Though bold in the seas of the North to assail

The morse and the sea-horse, the grampus and whale.

If your Grace thinks I’m writing the thing that is not,

You may ask at a namesake of ours, Mr Scott –

(He’s not from our clan, though his merits deserve it,

But springs, I’m inform’d, from Scotts of Scotstarvet;)

He questioned the folks, who beheld it with eyes,

But they differed confoundedly as to its size.

For instance, the modest and diffident swore

That it seemed like the keel of a ship, and no more –

Those of eyesight more clear, or of fancy more high,

Said it rose like an island ‘twixt ocean and sky –

But all of the hulk had a steady opinion

That ‘twas sure a live subject of Neptune’s dominion –

Popular depictions of the Kraken, such as those in Clash of the Titans (1981 and 2010) and Pirates of the Caribbean (2006), have come to define the public image of this semi-mythical creature. It is envisaged as a monstrous beast lurking somewhere under the ocean, surfacing to attack ships with its mighty tentacles, and devour entire crews of sailors in its fearsome maw.

Tennyson’s poem, however, paints a different picture.

His Kraken is grand and fearsome, but ultimately tragic. It possesses immense size and power, but immediately dies upon rising to the surface of the sea. A creature of nature, it is also unnatural; abhorred by the sunlight and unable even to dream in its endless sleep. It is a part of the world and apart from the world; it slumbers in the unknown depths with only polyps and worms for company and sustenance. The poem serves as a counterpoint to all those movie depictions of an aggressive predator crushing ships and devouring men in a blur of flailing tentacles. Like his tragic Lady of Shallot, Tennyson’s Kraken is sympathetic. And incredibly lonely.

Let’s begin with the overwhelming sense of depth and time in which Tennyson mires his creature. In this poem, time is geological: ancient, millennial, ages. The sense of depth at which the Kraken exists is also beyond mortal comprehension: below, deep, far, far beneath, far away. Tennyson locates the Kraken in the abysmal sea beyond the realms of our perception. Abysmal is a polysemic word firstly referencing the deep abyss of the sea while also meaning the abysmal conditions (cold, presumably, and dark and lonely) in which it resides. On top of this, the Kraken and its attendant creatures (worms, sponges, polypi) are associated with gigantic size: millennial growth and height, unnumbered and enormous, huge, with giant arms. If the Kraken is a natural creature it does not follow the rules of nature – time, spatial dimensions, normal processes of growth and decay – that govern the rest of the living world. Rather it is a paradoxical creature that lives in an impossible state; paradoxes are hinted at from the first line in which we are told that the creature slumbers in the upper deep, something of an oxymoron.

According to this paradox, the Kraken lives – but not in any way recognisable as living. The poem repeats three times that the creature sleeps/sleepeth and once adds slumbering. These verbs are always in the present tense as if this is the Kraken’s only state of existence. More than this, the Kraken is not even permitted the relief of dreams: it lies in dreamless, uninvaded sleep. The choice of word uninvaded both reaffirms his dreamlessness while also indicating that the Kraken’s realm is yet undiscovered and undisturbed by humankind. Despite those ever-present attendants, the poem’s mood is one of utter loneliness: the Kraken is condemned to live in darkness and even the sunlight abhors contact with this unearthly realm, preferring to flee. (Remembering those preconceptions we may harbour about the monster, this is the only moment at which the possibility it might be fearsome is suggested.)

Do we even actually see the Kraken? Once the faintest sunlight flees, the remaining light is described as sickly and faint. The appearance of the beast is barely sketched. We strain to see through dark, murky water but can catch only the vaguest glimpse of the monstrosity lurking there –shadowy sides – which is more of an impression than anything actually ‘seen’. At one point he is indistinguishable from the sea he inhabits, being ambiguously described as the slumbering green. Another thing that we may not have expected is the ponderousness of movement in the poem: battening is like ‘fattening’ or ‘gorging’ which suggests slothfulness and greed, not speed or agility; sleep, slumbering, lain, lie and battening are all motionless; swell links to millennial growth creating a sense of slow rather than quick movement. Only winnow is in any way graceful, summoning to mind the waving of spongey fronds in the underwater currents. Nowhere can be found the swift darting of a predator or the whirl of limbs capable of crushing ships to splinters.

Actually, the more you read, the more the Kraken seems like a victim of circumstance rather than an implacable, fearsome predator. Look at the way it sleeps under the weight of huge sponges which have grown on and around its body over thousands of years. Wondrous grot and secret cells could mean caves and holes in the sea floor; equally they could be cavities in the body of the Kraken itself. Winnow is a peculiar word normally used in agriculture to describe the stripping away of impurities in grain (as in ‘to winnow the grain from the chaff’ by throwing it in the air). Using it here suggests the gradual stripping away of the Kraken – its carapace or shell? – by the ‘polypi’ that tend to it. It is not clear whether these creatures (like the huge growths and sponges that surround the Kraken) are part of his body, fused with his biology over the passing of thousands of years, or part of the sea environment. I imagine it as the former because this makes the Kraken a more sympathetic creature. Despite its huge size, it is defenceless in sleep against the parasites that burrow into and sprout from its body. It doesn’t choose to live at the bottom of the sea – it’s trapped there!

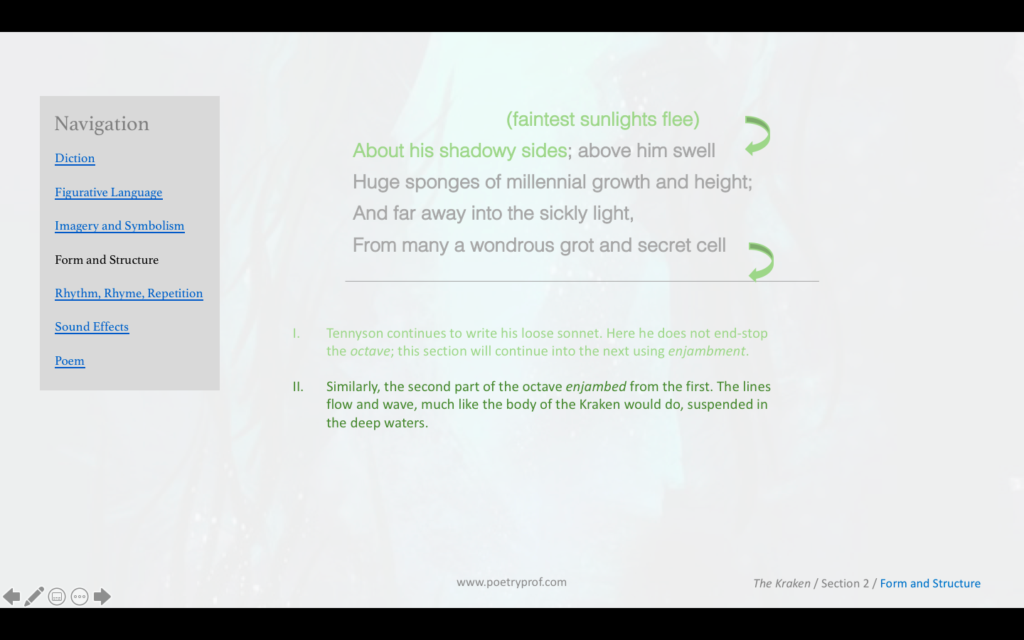

Poetic form is an essential component of this reading of the poem. Tennyson trapped his Kraken inside a sonnet as much as he pinned it beneath the weight of water and millennial growth. A sonnet is a traditional fourteen-line rhyme in iambic pentameter. The exact composition of the rhyme scheme depends on each style of sonnet: the three most commonly used are Shakespearean, Spenserian and Petrarchan, and each of these has its own specific requirements. Tennyson’s sonnet is a hybrid sonnet composed of different elements and, by the end of the poem, departs from formal requirements altogether. You have probably noticed already that the Kraken is fifteen lines long, not the required fourteen (the technical name for this is a stretched sonnet). Now take a close look at the rhyme scheme. The first quatrain of Tennyson’s sonnet follows the ABAB rhyming pattern of the Shakespearean form; but the second quatrain is rhymed CDDC – often associated with the Petrarchan form. The final septet is a highly unconventional: EFEAAFE. Even the meter is occasionally hard to scan, with anapests (de-de-dum) lurking among the iambs (de-dum) as the Kraken lurks unseen amongst the rocks. Of course, all this speaks to the poet’s intention: like his twisted sonnet, the Kraken itself is a mutation.

The sonnet form includes the expectation of a volta or turn; but where the turn is precisely located depends upon the type of sonnet: Petrarchan sonnets turn after the octave (first eight lines): Shakespeare liked to save his turn until the final couplet. Having not fully committed to either of these, Tennyson again enjoys confounding our expectations by ‘turning’ in the final three lines: the word until is our grammatical clue that everything is about to change (In a conventional fourteen line sonnet, this would be the final couplet – but the Kraken has fifteen lines). The Kraken finally stirs, and its latent power is awakened: the latter fire shall heat the deep… In roaring he shall rise. Where the Kraken has previously been obscured in the shadowy depths, now he is visible to all: by angels and men to be seen. The Kraken’s power is unleashed through stirring action: strong R alliteration in roaring… rise, plus the strong modal verb shall. Tragedy is, however, quick to follow: the moment the Kraken is allowed to uncoil and surface in all his splendour – he dies!

The association of the Kraken with the biblical Apocalypse (latter fire; angels) is one of the most ambiguous elements of the poem: did the Kraken cause this fire or is he a victim of it? The ambiguity suggests that mankind cannot know when Judgment Day will arrive. Lack of knowledge and certainty pervades the poem, central to the way the Kraken was depicted so obscurely. Ideas like this were central concerns of Gothic literature, which explored the terror of living in a world stripped of the reassuring comfort that absolute faith in the bible provided, but not yet secure in the validity of new scientific discoveries. The ending of the poem reminds us that in the Victorian world all kinds of scientific and religious ideas were swirling around, often conflicting with each other. Tennyson was a product of this time and would have been exposed to wildly conflicting sources: biblical texts, ancient mythology, scientific treatises, travellers’ tales, the discovery of dinosaur bones. What did Tennyson believe in? Was he predicting the eventual exposure of the Kraken as a mythical creature and lamenting the lost sense of wonder that sometimes accompanies scientific proof? Or is the Kraken a religious symbol of his belief in Judgment Day?

It’s even possible to read the latter fire shall heat the deep as a man-made apocalypse, in which case the Kraken was driven from his place of refuge by human activities: hunting, deep-sea exploration and such like. One of the great things about literature is how meaning and relevance can be rediscovered over time. Read the final three lines in the context of today’s widespread destruction of the sea bed and reduction in the marvellous wildlife of the ocean – and wonder whether Tennyson was prophesying when he wrote:

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Lady of Shallot by Alfred Lord Tennyson

A parallel can be drawn between the fate of the Kraken and that of Tennyson’s most famous creation, the Lady of Shallot, who was famously destined to die as soon as she defied a curse and left her tower imprisonment. Read it and see for yourself.

- The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats

Like Tennyson, Yeats conjures an image of the end of the world marked by the coming of a fantastical and terrifying creature. This poem contains the famous line, ‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold’ used by Chuinua Achebe as the title of his novella Things Fall Apart.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Kraken at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis and would like to discover more, you might like to download a bespoke study bundle for this poem. Costing only £2, the bundle includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive, fully illustrated and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on Tennyson’s adaptation of the Sonnet Form.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What do you think of Tennyson’s Kraken? Do you find him pitiable or fearsome? What do you make of the ending? Have you noticed any poetic features that we haven’t discussed? Leave a comment, ask a question, start a discussion. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.