Walter De La Mere scares his children – and us – with this mysterious fireside fairytale.

“…an artist who never lost sight of his childhood”

J.B. Priestley

There’s a nice story behind the origin of today’s poem: De La Mere wrote it at the request of his children for something scary to listen to at bedtime. Enjoyment of rhythm and rhyme, immersion in the sounds of the poetry, and the sinister quietude of the scene is the poet’s chief intention. It was subsequently published as the first in a collection entitled The Listeners and Other Poems and is the perfect way to set the tone: mysterious, ethereal, creepy, spooky.

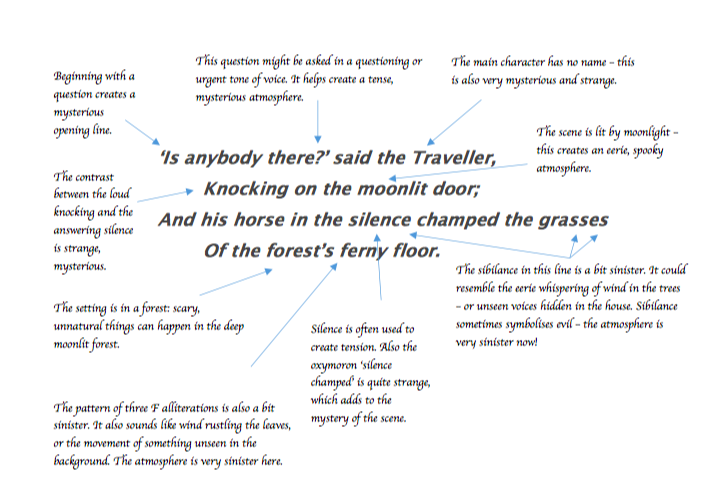

‘Is anybody there?’ said the Traveller,

Knocking on the moonlit door;

And his horse in the silence champed the grasses

Of the forest’s ferny floor.

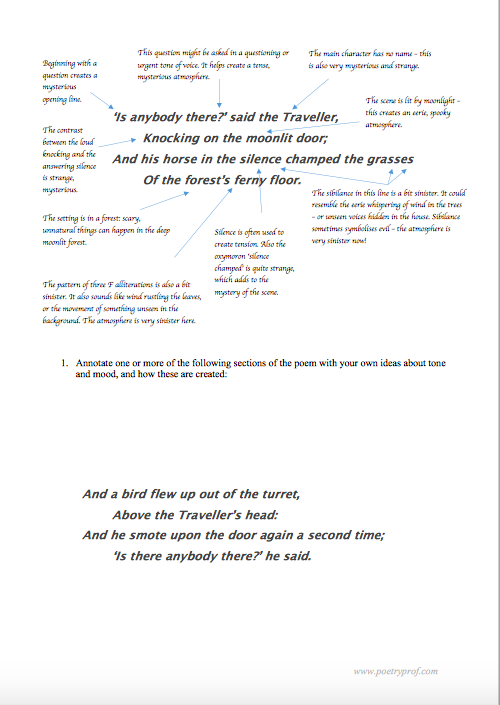

And a bird flew up out of the turret,

Above the Traveller’s head:

And he smote upon the door again a second time;

‘Is there anybody there?’ he said.

But no one descended to the Traveller;

No head from the leaf-fringed sill

Leaned over and looked into his grey eyes,

Where he stood perplexed and still.

But only a host of phantom listeners

That dwelt in the lone house then

Stood listening in the quiet of the moonlight

To that voice from the world of men:

That thronging from the faint moonbeams on the dark stair,

That goes down to the empty hall,

Hearkening in an air stirred and shaken

By the lonely Traveller’s call.

And he felt in his heart their strangeness,

Their stillness answering his cry,

While his horse moved, cropping the dark turf,

‘Neath the starred and leafy sky;

For he suddenly smote on the door, even

Louder, and lifted his head: -

‘Tell them I came, and no one answered,

That I kept my word,’ he said.

Never the least stir made the listeners,

Though every word he spake

Fell echoing through the shadowiness of the still house

From the one man left awake:

Ah, they heard his foot upon the stirrup,

And the sound of iron on stone,

And how silence surged softly backward,

When the plunging hoofs were gone.

Walter De La Mere had one of English poetry’s great imaginations. He revelled in creating fairy-tale worlds that could have come straight from a volume of children’s stories. A recurring motif in his work was an empty house – possibly, but rarely explicitly, haunted. In fact, so fond was he in crafting mysterious, supernatural settings that he even wrote a poem called The Empty House from which the following lines are taken:

See this house, how dark it is

Beneath its vast-boughed trees!

And later on…

‘Secrets,’ sighs the night-wind,

‘Vacancy is all I find;

…

No voice ever answers me,

Only vacancy.’

Although it doesn’t have the lilting, ballad rhythm of The Listeners, these lines could have been an early sketch of the mysterious house deep in the woods that our Traveller goes looking for.

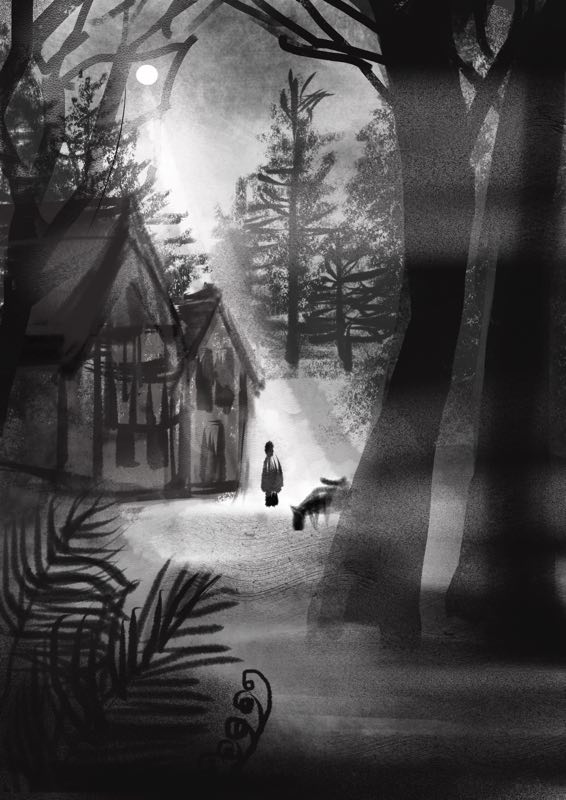

So to The Listeners. The scene is set: our mysterious hero rides through the forest by night, eerie moonlight, shadows, an empty house (a turret indicates it’s probably a mansion or even small castle) overgrown with ivy (leaf-fringed sill). The story is simple: the Traveller has to deliver a message to the house. He expects to find it occupied, but instead it appears to be empty – except for a host of phantom listeners, who are strongly implied to be the ghosts of the people who used to live in the house, though this is not apparent to the rider.

The story may be simple, but the joy of reading this poem comes from the richness of the setting and atmosphere. It’s a brilliantly described scene that contains all the ingredients for an eerie Gothic fairy-tale. The air is thick with tension. At one point a bird suddenly breaks cover, flying unseen above the Traveller’s head: it’s a classic jump-scare. Later, there is an image of some supernatural presence hovering right in front of him, staring into his grey eyes, but remaining invisible. A technique De La Mere employs masterfully to keep us off-balance is the liberal use of juxtapositions. At one moment we see the horse with his head down cropping the turf; the next our eyes wheel across a starred and leafy sky. The insistent cry of the Traveller is countered only by silence; an empty hall is paradoxically described as thronging. Creating wild oppositions heightens the impression of a fantastical, supernatural world in which you can never be sure what’s what.

Silence and stillness are other crucial ingredients to the tension of the scene. Right from the outset, it’s a strange, thick kind of quiet that is never really silent if you listen carefully enough. Fricative and sibilant alliteration is prominent: horse, silence, grasses, of the forest’s ferny floor. While soft, these sounds easily conjure the kinds of noises audible in the eerie forest scene, such as wind in the trees, the rustling of leaves or shuffling of small animals. Words such as dark, shadowiness, empty, and faint thin the atmosphere down so it’s almost incorporeal and create the perfect Gothic scene for the ghostly story to play out on. The house itself is described as dark and empty, lit only by moonlight and home only to that bird nesting in the turret.

Anyway, the atmosphere is quickly spoiled by our oblivious hero blundering in. Before you can say, ‘Knock, knock – who’s there,’ the Traveller has called out his question while knocking on the door. His horse stands behind him champing (chewing) the grasses. Both knocking and champing are onomatopoeias which has the function of making sounds louder and more vivid. The incongruity of these noises are highlighted through juxtaposition with the word silence: the oxymoron in the silence champed quirkily highlights the impossibility of silence while all this ruckus is going on.

While we’re at it, let’s take a closer look at De La Mere’s use of the plural grasses. It’s perfectly acceptable to use ‘champed the grass’, no one would bat an eyelid. To see the word in context, here’s the first four lines again with stressed syllables marked:

‘Is ā/ nybody thēre?’/ said the Trā/ (veller,)

Knōcking/ on the mōon/ lit dōor;/

And his hōrse/ in the sī/ lence chāmped/ the grā/ (sses)

Of the fōr/ est’s fēr/ ny flōor./

These lines follow a standard metrical pattern used in ballad poetry called anapaestic meter. It’s extremely hard to sustain for a whole poem, therefore you’ll see that each line is actually composed of an unpredictable mixture of iambs (for example, …ny flōor is read de-dum) and anapaests (And his hōrse reads de-de-dum). The rhythm is reminiscent of Alfred Noyes’ The Highwayman and it’s no co-incidence that both poems feature horses: you can hear the clopping of horse hooves running alongside the lines and imagine a perpetual traveller, always on the move. Even so, you can also see lines 1 and 3 are extended by further unstressed syllables (in brackets above): this technique, called catalexis, is one way of making sure your lines don’t have a strong, stressed ending. Lines that end on a ‘downbeat’ like this are written in falling rhythm; lines ending on an ‘upbeat’ are written in rising rhythm. Look carefully and you should see that (in the first twelve lines at least) the endings are juxtaposed – one falling, one rising. This juxtaposition complements the ones already used as well as throwing us off the beat a little and keeping us on edge. The same is true of the word knocking which is stressed-unstressed (the mirror of an iamb is called a trochee).

The sense of forward motion generated by rhythm is enhanced by careful repetitions, which work alongside rhyme (the whole poem follows an ABCB rhyme scheme) to generate that fireside-tale, scary-bedtime-story atmosphere. There are two major types of repetition at work in the poem: the first is the combined repetition of words, phrases and lines, in other words repetition as a language device. For example, De La Mare repeats words like moon, leaf, still, quiet. This sort of repetition is an important feature of song, and can also function like a chant or spell, lulling us and helping to thicken the tension of the scene.

Situational repetition, on the other hand, helps reveal the character of the Traveller and theme of the poem. Events that repeat themselves include: knocking on the door; the horse cropping the grass; the silence of the listeners. So as the poem continues and the situations repeat, we can see the Traveller becoming more and more agitated. He can sense the presence of unseen listeners inside the house and becomes frustrated at their refusal to reply. This frustration boils over in the following lines:

For he suddenly smote on the door, even

Louder, and lifted his head: –

‘Tell them I came, and no one answered,

That I kept my word,’ he said.

His emotion is emphasised through the combination of powerful diction with alliteration (suddenly/smote; louder/lifted). This time he speaks in the imperative tense (by which the verb is placed at the start of a phrase: Tell them) to give a command, as if he has run out of patience. The structure of the stanza is also revealing; do you see how the first line enjambs into the second? The disturbance to the rhythm derives from the Traveller’s disturbed emotional state.

At the end of the day, the poem raises more questions than it answers. It sets out its stall by beginning with an unanswered question and even contains the phrase: no one answered. Who is the Traveller? Where has he come from? Did he know the people in the house? Could he have been a relation of theirs? What happened to them? Did they die? How did they die? What was the Traveller’s duty? To whom? What is the significance of keeping his word? The only reward he – and we – receive is silence. I see the Traveller as a typical Walter De La Mare-type ‘wanderer’ figure (remember he also wrote a character called the Watcher). Being nameless, but having his role capitalized, draws attention to his being an archetype: Walter De La Mere loved epic and heroic stories (think Arthurian romance) in which this kind of mythical character is prominent. Descriptions of the man himself are very lightly sketched: grey eyes, lonely. Does ‘lonely’ refer to the setting – he’s the only one there – or is it an existential part of his being; is he always alone?

Interestingly, the final four lines of the poem reverse the perspective of the narration. Until this point, we stood with the Traveller outside the house looking in, wondering ‘Is anybody there?’ The listeners never respond. Then, suddenly, there’s an audible ‘Ah…’: like the connective that signals a turn or volta. After this moment, the Traveller fades away, and we remain standing alongside the listeners instead. Look how the sound dwindles: from foot in the stirrup, to the sound of iron on stone (horseshoes galloping away) to silence surging backwards, then finally even the plunging hoofs were gone. Honestly, all interpretations are up for grabs here: did the Traveller simply leave? Or is something else going on? Did he die? Was he dead all along, and actually it’s the listeners who are alive (I like this one, it explains why they live happily together in a house like normal people and he’s so lonely)? Here’s one that’s really meta: given we’re left standing with the listeners at the end, could it be possible that the Traveller’s untold quest was to deliver us – the readers! – to the house of the dead?

I find it quite fun to explore possibilities like this. The connections and comparisons between the Traveller and the listeners are frequent, so it’s not too outlandish to suppose that they have traded places. The latter exist in a host and are associated with thronging whereas the Traveller is pointedly lonely. It’s almost as if they have achieved a companionship in death that he lacks in life. Sometimes a word describes the Traveller and, on another occasion, describes the listeners: in line 12 he stands perplexed and still while in line 22 it’s their stillness answering his call. Both are unnamed. Make of this what you will. Your response to all this mystery probably depends on what kind of reader you are: do you get frustrated when writers don’t explain what they mean, or do you enjoy imagining the secrets of the scene? In this way, the poem’s ‘hidden’ theme might be futility: the futility of completing a quest with no reward, the futility of keeping your word to those who have already gone, the futility of living a life that can only end in death – ultimately, the futility of looking for secrets hiding in a poem that doesn’t intend to share them.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix by Robert Browning

This poem, like The Listeners, is written in anapaestic meter; the subject matter is a courier delivering good news on horseback.

- The Empty House by Walter de la Mere

This poem could have been the prototype for The Listeners. Abandoned old house? Check. Spooky forest setting? Check. Moonlight? Check. There’s even an unnamed protagonist called the Watcher…

- The Highwayman by Alfred Noyes

This can be read as a companion-piece in that both poems employ the ballad form to tell a captivating narrative. And both have horses in them.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Listeners at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis and would like to discover more, you could download our bespoke study bundle for this poem. Normally these resources cost £2, but this time we’d like you to try out the materials for free. The download includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on tone and atmosphere.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap activity or revision.

- 4 practice essay questions with help and advice – and one complete essay plan for you to use.

And… discuss!

What did you think of Walter De La Mere’s poem? Who do you think the ghostly listeners might be? How did you interpret the reaction of the Traveller? Let other people know what you think by leaving a comment below.