Boey Kim Cheng reveals the sinister side of relentless urbanisation in this poem that delivers a timely warning.

“Boey has always felt like an outsider, and considers that poets are banished to hover on the edges of society…”

From an interview with Boey Kim Cheng by the Sydney Review of Books

As any reader of good science fiction knows, there’s no such thing as the perfect society. We love to imagine that our modern lives are free, easy and that technology helps make the world a better and more convenient place. But, as prescient authors from George Orwell to Aldous Huxley, Frank Herbert to Isaac Asimov, remind us – there’s always a price to pay. In the case of Cheng’s poem, it’s the titular Planners’ obsession with order and regimentation that turns what could be a utopian paradise into a dystopia, where convenience and efficiency come at the cost of warm human relationships, spontaneity, and the freedom to imagine alternative ways of living.

They plan. They build. All spaces are gridded, filled with permutations of possibilities. The buildings are in alignment with the roads which meet at desired points linked by bridges all hang in the grace of mathematics. They build and will not stop. Even the sea draws back and the skies surrender. They erase the flaws, the blemishes of the past, knock off useless blocks with dental dexterity. All gaps are plugged with gleaming gold. The country wears perfect rows of shining teeth. Anaesthesia, amnesia, hypnosis. They have the means. They have it all so it will not hurt, so history is new again. The piling will not stop. The drilling goes right through the fossils of last century. But my heart would not bleed poetry. Not a single drop to stain the blueprint of our past’s tomorrow.

Cheng is a Singaporean poet and was born and raised in one of the world’s fastest growing, modern, and high-tech cities. Famously touted as an urban success story, behind the scenes what deals and compromises played a role in Singapore’s development? Perhaps the city’s wealth and glamour has not come without a price. Therefore, while not explicitly about Singapore per se, it’s easy to draw parallels with Cheng’s homeland and the nameless city in the poem. On the surface everything is perfect; the streets are bright and clean and safe. Much thought has clearly been given to design, both for functionality and aesthetics: roads meet at desired points, buildings are in alignment with the roads, bridges hang gracefully. The diction of the opening verse – the first six lines or so, anyway – is largely positive. Words like possibilities, grace, linked and desired suggest everything is working as planned, there are no snarly traffic jams, dead-end alleyways or unsightly, dilapidated areas to spoil the city. Throughout the opening verse, Cheng employs a mixture of concrete and abstract words. Concrete words describe objects and places, things like buildings, bridges and roads. Abstract words like grace, and desired express concepts linked to aesthetic beauty (grace) and the future (desired, plan, possibilities) as if the city has not finished expanding, or that living in such a place can bring beauty, opportunity and possibilities into people’s lives.

Under the aesthetically pleasing surface of the city, though, the first seeds of doubt are sown. While superficially appealing, there’s also something ominous about the opening verse. Mixed with the positive diction are words from the lexical field of mathematics and engineering: plan, spaces, gridded, linked, alignment, permutations and points. By itself, there’s nothing particularly sinister about this, of course, and the idea that building a city relies heavily on maths and science shouldn’t disturb anybody overmuch. However, the impression slowly grows that the controlling minds behind the construction of this vast city are more mechanical than man, algorithmic rather than organic. The seventh line, They build and will not stop, eerily echoes a line from science fiction cinema describing a merciless, pitiless artificial intelligence that is incapable of feeling human emotion.

Therefore, the first verse culminates in an ominous-sounding image couched in the language of battle: Even the skies draw back and the seas surrender. Two elements of the natural world that should be out of the reach of human development are instead personified as being defeated in a war, retreating from the unstoppable onslaught of concrete and steel. An undercurrent of sibilance accompanies these statements; as well as bringing to mind the sound of the wind and tide as nature retreats, sibilance can be associated with sinister or evil forces. A side-effect of the personification at the end of verse one is it draws attention to the odd lack of any people in the city at all. While structurally perfect and aesthetically impressive, it doesn’t feel as if anybody actually lives here. And it’s not just people: nor are there any parks, trees, cats, dogs or birds. It feels like there’s no room to breathe in a city like this, that’s planned with efficiency first and foremost in mind.

The form of the poem is important in creating this claustrophobic effect. Cheng isn’t afraid to use full stops abruptly, as in the first line: They plan. They build. Purposeful breaks and stops in the middle of lines of poetry are called caesura; this use of full stops to ‘compartmentalise’ and structure the layout of his writing is a feature of the poem, and I’m sure you can find more examples. Cheng is being as economical with his language as the Planners are with the spaces in the city, as if every last inch of use is squeezed out of every square meter of ground. Caesura also breaks lines up into blocks, much like buildings in a city might look. Enjambment (the flow of one line of poetry to the next without break or pause) is often used as a counterpoint to caesura as it easily creates a sense of flowing movement, but in this poem it rather adds to the building-block effect – there’s no wasted space, no unnecessary pause to distract from the effort of construction and expansion. Lines that flow smoothly down the page can represent the constant, unceasing expansion of the urban environment and, by writing in lines of different lengths, if the poem is turned on its side, the lines resemble towers of various heights pressed against one another. You can use the term spatial form to refer to the way the layout of a poem on the page represents an aspect of the poem’s meaning in this way. To evoke this relentless, unceasing urban expansion, Cheng uses various forms of repetition very effectively. You can find anaphora (the repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of lines, such as They have the means… they have it all…) epistrophe (repetition of phrases at the end of sentences (…will not stop) and parallelisms (identical sentence structures: The piling… the drilling… andThey plan. They build.) effectively deployed throughout the poem.

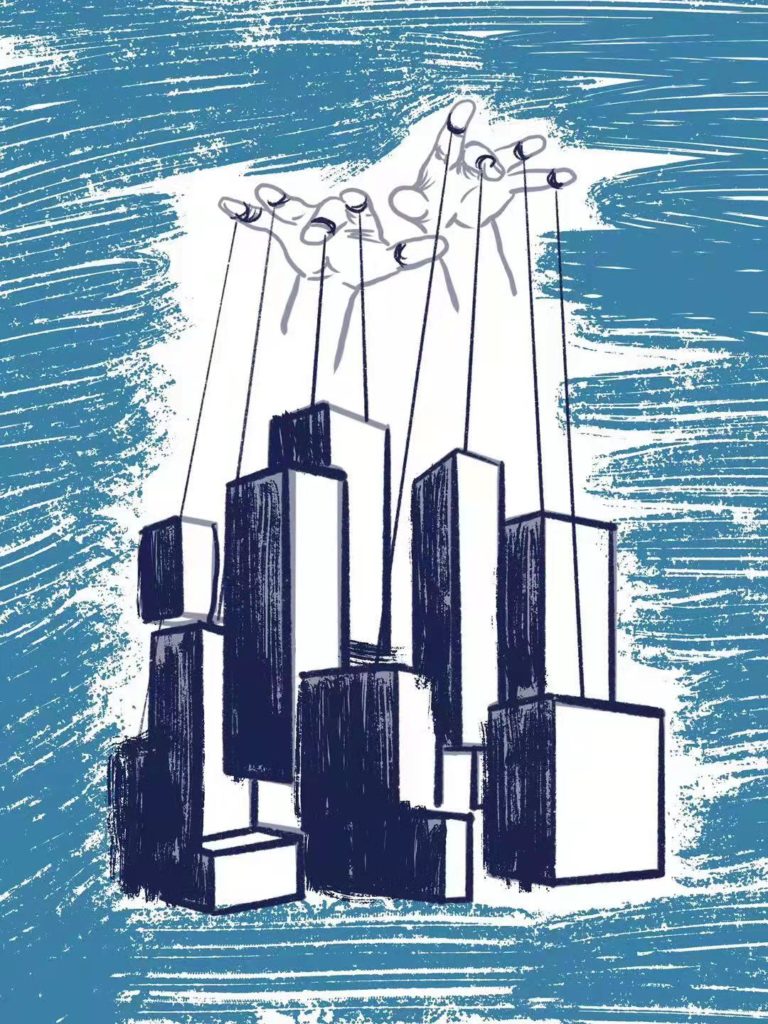

The obvious and notable exception to the lack of any actual people in the poem are the titular Planners. Who are they? What do they look and sound like? Cheng wisely keeps them faceless and hidden in the shadows. They feel like emotionless bureaucrats, only concerned with controlling and directing urbanisation. They exhibit no feelings or care, beyond the desire to keep the city expanding and developing. Apart from the poem’s title, Boey Kim Cheng never mentions their names, referring to them using the personal pronoun they. Perhaps we could better refer to this as an ‘impersonal’ pronoun, because this little word separates the Planners from us, keeping them at a distance from the reader. We cannot get close to them, or put faces to the name; being able to visualise who they are would make the Planners more human and relatable, and lessen the discomforting feeling that they definitely do not have our best intentions in mind. You might like to count the recurrence of the word they: twice in the first line; three times in the first verse; six times in the whole poem. It’s partly this repetition that creates the sinister sense that the Planners are lurking in the background, always watching, checking and planning their next move.

In verse two, Cheng recasts the Planners as sinister dentists, employing the extended metaphor of dentistry to draw parallels with the responsibilities of those in charge of urban planning: maintaining a ‘healthy’ infrastructure, straightening ‘crooked’ parts, drilling out rot and decay, ensuring the final result is clean, white, free of blemishes. The cosmetic benefits of dental procedures are implied using words like capped, plugged, gleaming and shiny, amongst others. The brightest image in the metaphor is that of all the shiny new buildings gleaming gold, an image positioned side by side with the next like two perfect rows of shiny teeth. But these images are not meant to be reassuring or pleasant. Listen to the hard consonant sounds of these few lines of poetry: guttural G and hard CK mix with plosive P (gaps are plugged with gleaming gold); dental D and T sounds combine (dental dexterity) – all blend together in a way that sounds discordant and unpleasant. This unpredictable collection of colliding sounds is called cacophony and Cheng uses this technique to evoke the mechanical thumping sounds of constant piling and drilling and to remind us that violence against the natural world is an inherent part of construction that will not stop, no matter how big the city becomes.

This part of the poem is a masterstroke, in my opinion. Simply the thought of dentistry is enough to arouse fear and discomfort in many people; the deranged dentist is a popular culture and horror archetype and Cheng’s dentists are surely not avuncular people with a ready smile to take your fears away. While you’re strapped sedated into the chair, they perform much more sinister acts upon you. Along with your teeth, they extract other essential qualities that can’t necessarily be quantified. Charisma, individuality, joy, spontaneity, and imagination are all fair ideas, and you should feel free to interpret this part of the poem in your own way. Whatever you decide, Boey helps us to understand that, like a person with a sad addiction to plastic surgery, the city comes out of the ‘operation’ looking superficially dazzling from the outside, but completely soulless on the inside.

Here’s where the extended metaphor of dentistry really comes into its own. Dentistry is a painful process, but the pain can be numbed through anaesthesia, a drug with side effects that include lethargy, forgetfulness and even blissful euphoria. As in another famous dystopian novel, drugging people helps brainwash them into a state of ignorant bliss that is not real. Back in Cheng’s poem, citizens are numbed to the downsides of ceaseless urbanisation, their minds dulled to the point where they develop amnesia, meaning forgetfulness of the past, or of alternative ways of living. The eighth line of the second verse is a simple tricolon consisting of only three words: anaesthetic, amnesia, hypnosis. These are the real weapons in the planners’ arsenal. By removing the pain of the operation, the patient is lulled into believing that no damage is being done. For a tiny taste of the effect of the Planners’ medications, listen to how the sounds of construction recede into the background after their drugs have been administered. Loud cacophony is suddenly replaced by assonance, long vowels that mix with nasal M / N and sibilance – soft sounds that evoke the sensation of being lulled into a drug-induced haze. Of course, in small doses, there’s nothing wrong with a bit of anaesthetic to take the pain of a dental procedure away; on the other hand, I wouldn’t want to live my whole life strapped unaware in the dentist’s chair.

Cheng shows us that The Planners’ sophisticated methods of control allow them not only to colonise space, as we saw in the first verse, but to rebuild time as well. A reader of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four will no doubt be reminded of the famous line, ‘Who controls the past… controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’ Orwell was telling us that totalitarianism aspires not only to control people’s actions and behaviour, but their minds as well. This is ultimately one of the most disturbing aspects of verse two: The Planners want people to believe that their version of life is the ‘natural’ world, that it’s the way the world is meant to be. The second verse ends with an invisible act of cultural vandalism as the planners drill right through the fossils of last century. They don’t care about history, cultural heritage, the natural world or the past; all they care about is their shiny new waterside developments – and nobody seems to notice, even when they absolutely will not stop despoiling all those things that, by rights, belong to everybody.

At the very end of the poem, Boey Kim Cheng places himself in opposition to the Planners’ grand design. What they stand for – bland efficiency, convenience, shallow superficiality – he opposes. The sudden juxtaposition of the little word my with they is the poet using the personal voice; this is how poets write when they present their own, personal viewpoint in a text. The most important image in the last verse, but my heart would not bleed poetry, is vivid and shocking. ‘Blood’ is a universal symbol of somebody’s life force, something that the anodyne city leeches out of the people who live there, and ‘blood’ can represent a range of other ideas as well: a wake-up call or rally cry; an image of protest; the risk and danger a person puts themselves in when they speak up against popular opinion or governmental forces; a reminder of the violence against the natural world inherent in the construction of our vast cities. I encourage you to interpret this powerful image in your own way.

The final line of the poem is something of a warning, alluding once again to Orwell’s famous reminder that ‘who controls the past controls the future’. If the Planners are like Big Brother then Cheng himself is Winston, carving out a little niche in the corner of his room, outside the range of telescreens and surveillance devices, his poem a small act of defiance against those who would deny his essential humanity. As a writer, Cheng values individuality, creativity, spontaneity, improvisation – all the mercurial qualities of poetry that have no place in the planners’ grand designs.

Suggested poems for comparison

- London by William Blake

A famous indictment of the corruption of city life. Blake’s London is a desperate place, crammed with people who’s faces bear the marks of sadness and woe.

- Cities by Hilda Doolittle

Doolittle imagines a city of ‘dark cells’, teeming with people crowded into few tiny streets, everything cast in black shadows. A powerful poem from the Imagist movement.

- Reservist by Boey Kim Cheng

From his anthology collection Boys to Men, Cheng turns his critical eye on the institution of National Military Service in Singapore.

- Boxes by Sampurna Chattarji

Chattarji is a poet from Mumbai and, like Cheng, evokes images of life lived in tiny compartments, where every square inch of space is used for something and even the plants on tiny balconies struggle to breathe.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Planners at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample analytical paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on the connotation of words

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

What did you think of this analysis of Boey Kim Cheng’s poem? Apart from Orwell’s 1984, did the poem remind you of any other dystopian text? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. And, for nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

thank you for this, this is helpful for my IGCSE English assessments! Additionally, I also feel that the irregular stanzas and free verse of the poem oppose the idea of organization and structure promoted by the planners, depicting the poet’s slight protest to this notion

That’s a really good comment – I totally agree.

Hi. I have bought a Super bundle from you 3 years ago and found it very useful. I am looking for a super bundle on the poems listed below. This is the IGCSE syllabus for 2023-25. Can you help me with this? Didnd know how else to reach out to you. 🙂

From Songs of Ourselves Volume 1, Part 4, the following 15 poems:

Margaret Atwood, ‘The City Planners’

Boey Kim Cheng, ‘The Planners’

Thom Gunn, ‘The Man with Night Sweats’

Robert Lowell, ‘Night Sweat’

Edward Thomas, ‘Rain’

Anne Stevenson, ‘The Spirit is too Blunt an Instrument’

Tony Harrison, ‘From Long Distance’

W H Auden, ‘Funeral Blues’

Thomas Hardy, ‘He Never Expected Much’

Fleur Adcock, ‘The Telephone Call’

Peter Porter, ‘A Consumer’s Report’

Judith Wright, ‘Request To A Year’

Charles Tennyson Turner, ‘On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book’

Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Ozymandias’

Stevie Smith, ‘Away, Melancholy’

Hi,

Thanks for your comment. I’m glad the resources you bought were useful. You may have noticed it takes a while to prepare each poem and all the resources, so it will be some time before the next super bundle is ready. I’ll be posting individual poems along the way, so you can come back to visit from time to time. In the meantime, there’s another poetry selection for the same syllabus, poems for 2022 – 2024, which are already on the blog and you can buy as a super bundle.

A very thorough analysis! I am also preparing learners for 2023 IGCSE literature examinations! Very helpful indeed!!

Hi! I’m also waiting for the super bundle for IGCSE Literature Songs of Ourselves – Volume 1, Part 4 (the first selection). Hope to see it soon available for purchase. Many thanks.

Thank you for this thorough and very insightful analysis of the poem. I am preparing students for their IGCSE Literature exam, and this will certainly help!