Imtiaz Dharker’s poem exposes institutional xenophobia through a demeaning interaction.

“Dharker’s poems… inform us of moments of violence that one needs liberation from.”

Nandini Varma, writing in Creative Yatra

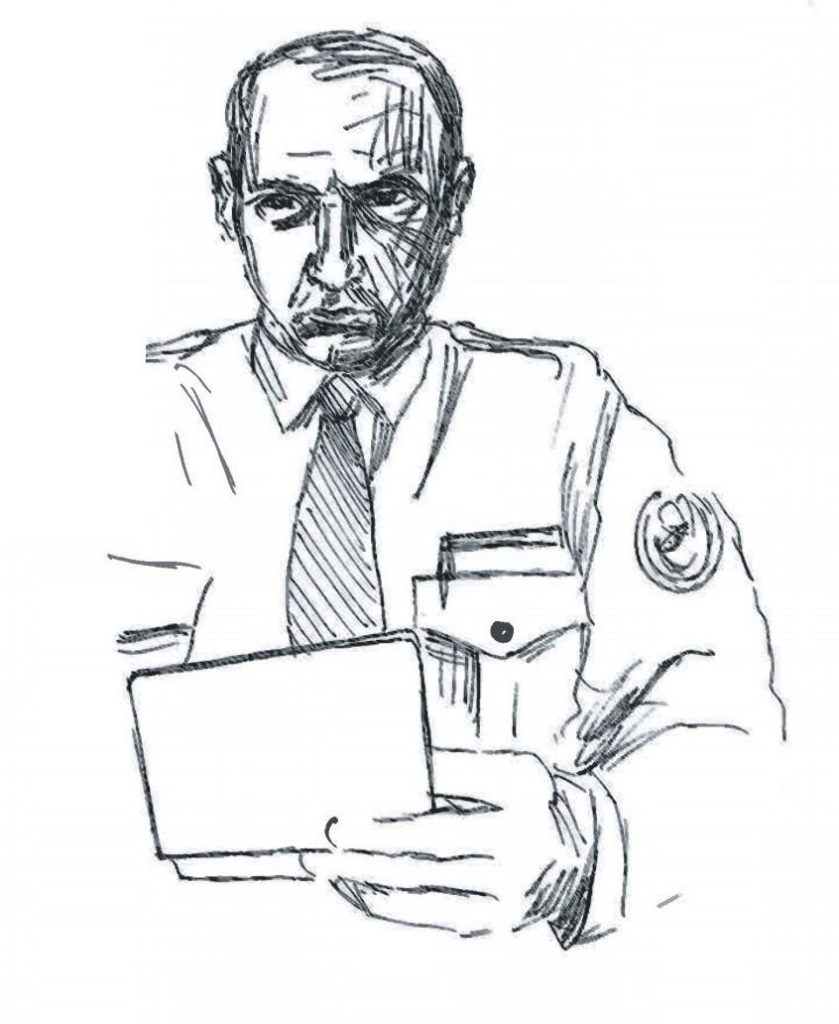

I don’t know about you, but when I go through airport immigration counters, I always feel a little uncomfortable. The moment when that red stamp hovers in the air as a uniformed official’s eyes flick back and forth from my passport to my face can seem to stretch unnaturally long. No matter how many photocopies of my itinerary I’ve pre-prepared or how legitimate my business abroad might be, I think that second or two of worry and self-doubt is universal. I’m all too aware of my status as an outsider, afraid that a small misunderstanding or filling in a form wrong might bring down the wrath of the immigration officer. I once overstayed a visa, so I recognise all too well that pit-of-the-stomach sinking feeling of being wordlessly escorted into a scary-looking office. My mistake was handled swiftly and professionally – but that didn’t stop images of harsh interrogation, intrusive searches, and locked doors flashing through my mind. Of course, my experience was a walk in the park compared to how people of colour, certain religions, different ethnic backgrounds, having a ‘type of face’ – or any number of other identifying features – are made to feel. Today’s poem is set at an immigration counter as Imtiaz Dharker returns from one of her frequent trips abroad (a writer, artist, and filmmaker, she divides her time between London and Mumbai). A British citizen her entire life, but born in Pakistan so she has dark skin and a name that is unfamiliar to the officer at the immigration counter, where a white passenger with the same colour passport might be waved on through (and maybe hear a friendly ‘have a nice day’ to boot) she is subject to prolonged and uncomfortable scrutiny that lasts the duration of the poem:

You hand over your passport. He looks at your face and starts reading you backwards from the last page. You could be offended, It makes as much sense As anything else, given the times we live in. You shrink to the size of the book in his hand. You can see his mind working: Keep an eye on that name. It contains a Z, and it just moved house. The birthmark shifted recently to another arm or leg. Nothing is quite the same as it should be. But what do you expect? It’s a sign of the times we live in. In front of you, he flicks to the photograph, and looks at you suspiciously. That’s when you really have to laugh. While you were flying, up in the air they changed your chin and redid your hair. They scrubbed out your mouth and rubbed out your eyes. They made you over completely. And all that’s left is his look of surprise, because you don’t match your photograph. Even that is coming apart. The pieces are there But they missed out your heart. Half your face splits away, drifts onto the page of a newspaper that’s dated today. It rustles as it lands.

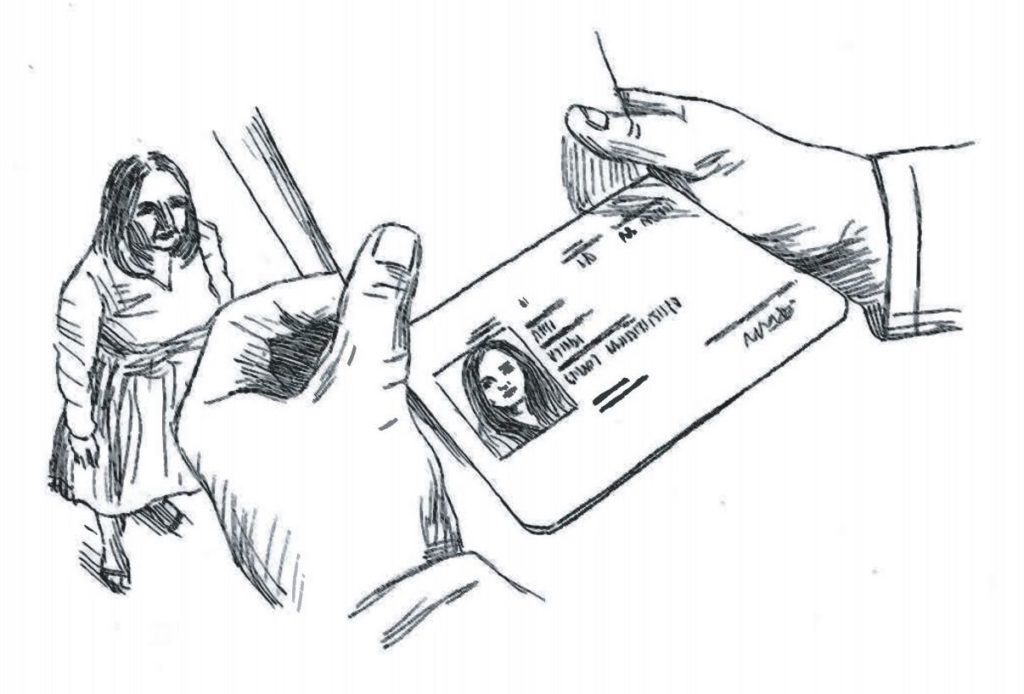

While my intro suggests that feeling uncomfortable at immigration is something universal that we can all relate to, the poem reveals how much more hostile this interaction can be for people of minority ethnic backgrounds in Britain (and not only Britain, I’m guessing, but the western world more widely). Published in 2006, the poem is part of the collection The Terrorist at My Table, and it’s impossible to ignore the wider context of Islamophobia alluded to by the poem’s title and refrain: the times we live in. In general, Islamophobia has been on the rise since the World Trade Center attack in 2001. More specifically, we live in a world where a recent American president tried to implement a ‘Muslim ban’ against flying to the US and disgraced himself by mocking the family of a deceased Muslim-American soldier who had been honoured for bravery. The poem explores the effects of xenophobia more intimately, by putting the reader in Dharker’s position as she passes through airport immigration on her way into the UK. Trying to bridge the gap between your experience and hers, one of the poem’s defining features is the way it speaks to you directly, using the second person perspective to help you walk in her shoes and get a flavour of how demeaning it is to be scrutinised so intently and with such suspicion all because of your appearance: the word looks appears in the second line, is repeated in verse four, and again in verse five to suggest the interaction goes on far too long to be comfortable.

The official staffing the immigration counter has noticed a couple of things that have triggered a red flag warning. Her name (Imtiaz is the writer’s first name) contains an unusual letter Z, unusual in Britain and other Western countries anyway, and she’s just moved house so there’s a discrepancy between addresses. Apparently, there are some visual differences between the passport photograph and the woman in the flesh (for example, the birthmark shifted recently suggests she may have aged) and the poem builds up to the admission that you don’t match your photograph, which seems to come as much of a surprise to herself as it is to the immigration official. This line reminds us that a photo is good at capturing what you look like in a single moment but not much more and photographs can soon be outdated. While small changes in appearance over time, not to mention moving house, are perfectly natural and innocuous, when confronted by a dark-skinned woman, these details arouse the immigration officer’s suspicion. Through his reaction, Dharker reveals how prejudice and xenophobia are baked into the system the official represents. She’s not accusing him as an individual of being racist, per se; it’s that his training has biased him to treat people who fit a certain profile with suspicion. Keep an eye on, nothing looks the same, you can see his mind working, he looks at you suspiciously, and even the birthmark shifted recently (a variant form of shifted is the word ‘shifty’) all convey the automatic paranoia of people who respond to appearance first.

As the pattern of humiliation unfolds, we see how scrutiny leads to suspicion leads to objectification. Almost immediately she feels invaded by him reading you backwards rather than simply checking her passport details. Not only does this point to a certain lack of logic (reading backwards is a poor way of understanding something), but through a special type of metaphor called metonymy, the whole of her identity is reduced to her passport (she calls it a book as if it contains her entire life story rather than travel stamps and basic info) which becomes a symbolic stand-in for her in the mind of the official. Metonymy is not that uncommon in spoken language; you might be familiar with the way people refer to the President of the United States as ‘the White House’ or how your new car is ‘a great set of wheels’. If you call a clever friend ‘Specs’ you’re using metonymy too. Maybe after reading this blog you’ll come up with a new nickname, as Dharker helps us see the reductive effect of metonymy through the image: you shrink to the size of the book in his hand. Once he conflates her and her passport as one and the same, he’s already begun objectifying her – and as soon as a person is seen as a mere object, dehumanisation is only one small step down prejudice’s slippery slope.

As one of the key images in the poem, the shrinking feeling she experiences implies the power imbalance inherent in this interaction. Dharker’s a single individual whereas the immigration officer represents an entire system and you hand over your passport suggests a surrendering of personal autonomy; now he’s holding her life in his hands. From this moment onwards she is completely passive. All she can do is stifle her upset lest anger lands her in greater peril: you could be offended and what did you expect? are expressed in a tone of resigned frustration, the rhetorical question implying that this kind of treatment is commonplace. Her only concrete action is a single, exasperated laugh which reveals both incredulity at the way she is treated and her humiliation throughout the ordeal. By contrast, the immigration official takes actions and makes decisions; frequent verbs are attributed to him and his colleagues: he looks… and starts reading… his mind working… he flicks to your photograph… not to mention the extended passage where we see the ‘real her’ replaced by his preconceived idea of her: redid, changed, rubbed, scrubbed. The form of the poem helps us feel her distress: written in free verse, Dharker’s verses are unequal in length and do not follow a set meter or rhyme scheme. Instead she uses unpredictable verse lengths, line lengths, infrequent rhymes (such as photograph/laugh, eyes/surprise and away/today) and other structural features combine to replicate the unpredictability of the encounter. From the first line onwards, Dharker mismatches the poem’s lines and sentences (this technique is called lineation). The first sentence ends after the word passport, but Dharker adds He… onto the end of line one before using enjambment to connect the first and second lines, emphasising the transfer of power from her to the immigration officer and suggesting that she’s not in control of what happens to her next.

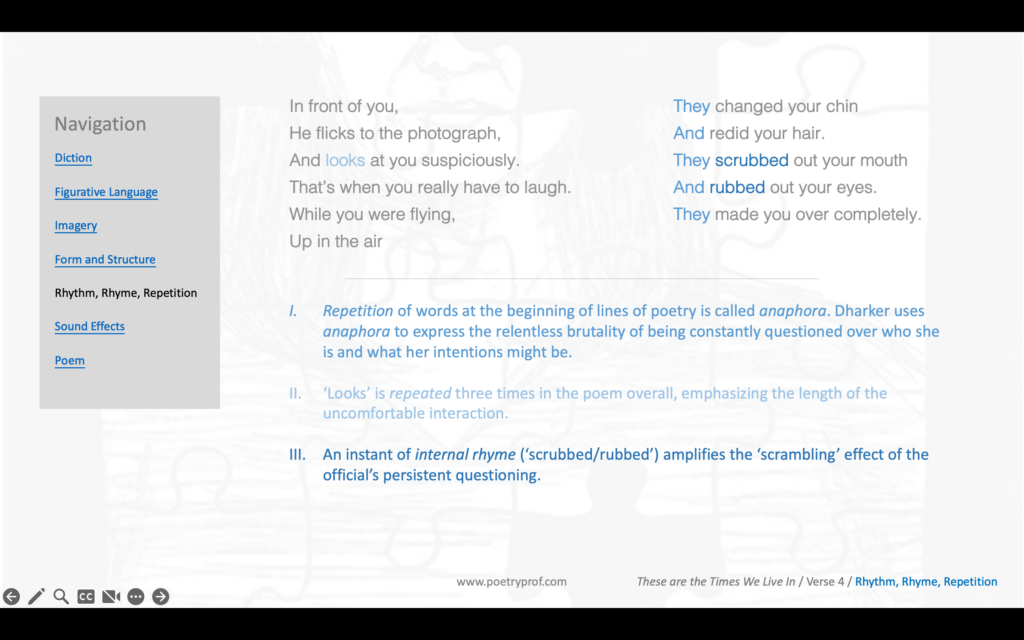

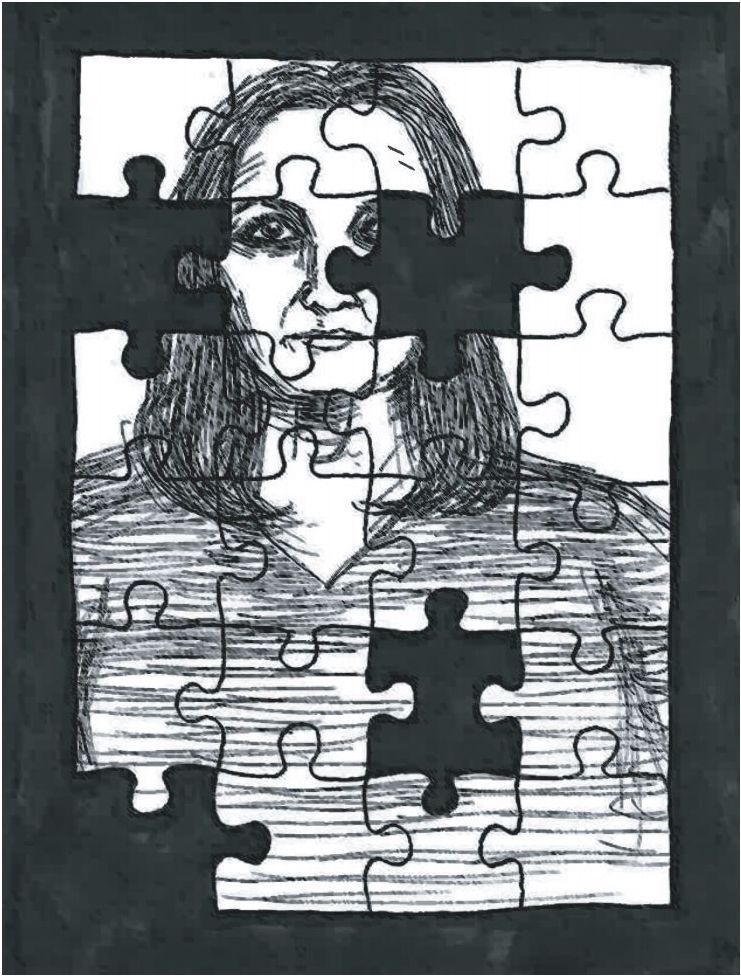

Dharker reveals how such demeaning interactions, repeated over time, rob a person of self-autonomy – she no longer has the power to define her own identity; the ‘truth’ of who she might be is decided by others. These ideas are uncomfortably brought to life in an extended metaphor running through the poem’s core, a place where she is robbed of agency and made totally submissive while others decide who she is and whether she constitutes a ‘threat’ – ideas triggered by her Muslim name and dark skin. The parallelism (structures, such as a sentence pattern, that are placed side-by-side) they + verb + your… renders her immobile during the scrutiny of her face, where her identity is replaced by their preconceived ideas of who she might be: They changed your… redid your … they scrubbed out your … rubbed out your … all culminating in they made you over completely. Both anaphora (repetition of words at the beginning of lines of poetry) and sound effects imply the relentless brutality of this disturbing transformation: changed your chin employs alliteration and an instance of internal rhyme (scrubbing/rubbing) scrambles up similar sounds to imply the way she feels all scrambled up by relentless questioning, doubting, and suspicious probing.

However, at the end of all this, her identity is never sufficiently established to the satisfaction of others. Phrases such as all that’s left, you don’t match and coming apart imply that she’s constantly being made and unmade, pulled apart, stuck together, and pulled apart again before the glue is even allowed to set. Words for various parts of the body are scattered everywhere: face, hand, eye, birthmark, arm, leg, chin, hair, mouth, eyes again. All the pieces are there, but the poem doesn’t combine them into a coherent whole, suggesting a fractured sense of personal identity. The use of personification in it just moved house and the birthmark shifted recently creates the impression that she’s not the owner of her own identifying features – misconstrued and reconstructed by others, the ‘truth’ of who she is is not up to her to decide. In fact her heart, symbolising her sense of self and representing who she truly is, remains left out of the picture they have drawn. Sitting at her core and representing emotions, experiences, and memories, it’s the one part of her body that no-one looks for or cares about getting to know. These are the Times We Live In is actually a sequence of three poems; the image of being violently erased and redrawn by somebody else reappears once more near the end of the sequence:

They got an eraser as big as a house and they began to use it to delete your life, the names of your lanes and roads and streets, your stories and your histories, your lullabies. They rubbed out your truth, and they left in your lies. They snatched your family portraits, shot them all over again with different people, started from scratch. They took your books and broke their backs cracked their spines, the margins gone, all the lines jumbled together, pages torn.

Dharker’s British: she came to the UK aged one, lived in Glasgow, her first husband was Welsh; her life experiences are defined by the same cultural forces as the staff at the airport! Yet she’s made to feel un-British every time she passes through these checks. Although the poem doesn’t say, presumably this happens at the other end of her trips; flitting between London and Mumbai (she divides her time between two countries now) when she arrives in India and presents a British passport, she’ll be treated as an outsider there as well. The phrase up in the air denotes her flying from place to place yet at the same time this is an idiomatic expression; when things are left up in the air they are uncertain or undecided. That she doesn’t get a say in the defining of her own identity is clear from the line they scrubbed out your mouth, a potent image of silencing. Instead, Muslim identity is defined by external forces such as the mass media, symbolised by the newspaper that sits at the immigration officer’s elbow. At the end of the poem when half your face splits away and drifts onto the page of a newspaper dated today, this powerful image acknowledges how the mass media interacts with the officer’s xenophobic training to create the hostile environment of immigrants’ lives. The way half your face onomatopoeically rustles on the page of the newspaper creates the subtle auditory impression that xenophobia and institutional racism is a constant white noise in the background of Dharker’s life.

Some people might argue that there is a case for inconveniencing others for the sake of the greater good. But Dharker’s poem asks us to think about who is more likely to be singled out for this kind of treatment. Like I said in my intro, it has happened to me – but only once in my life and that was my own fault (I’m white British, by the way). Dharker’s an award-winning writer, artist and filmmaker who’s lived in Britain longer than I have. I wonder how many micro-aggressions of this sort she’s had to tolerate. Hundreds? Thousands? What if the passive-aggressive behaviour she encounters at immigration is also directed towards her at the post-office counter, the hospital waiting room, in a job interview, at school – in any of the myriad public spaces that make up the fabric of wider society? Does a day go by where her identity isn’t prodded, poked, taken apart and put back together by someone who ‘just wants to make sure’? Trying to bridge the gap between your experience and hers, one of the poem’s defining features is the way it speaks to you directly, using the second person perspective to help you walk in her shoes and get a flavour of the demeaning hostility she is made to feel.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- I Need by Imtiaz Dharker

Dharker describes herself as “a Muslim Calvinist in a Lahori household in Glasgow and was adopted by India and married into Wales.” Published in the same collection as These are the Times We Live In, I Need blends experiences from different cultures – British and Indian – to suggest a person cannot be simply labelled ‘this’ or ‘that’.

- The Immigrant by Aline Mello

A Brazilian immigrant now living in Atlanta, Aline’s poem recalls her decision to move to America: in her own words, “…looking for my first passport and running into mountains of papers and documents that I know, as an immigrant, I need to have saved.”

- First Light by Chen Chen

Telling the story of a nighttime departure from China, Chen’s poem unfolds in flashing, half-remembered images. This poem is more about the place that’s left than the place arrived in, and reminds us that leaving involves loss and heartbreak too.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying These are the Times We Live In at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how to recognise metonymy.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Imtiaz Dharker’s poem? Do you identify with her experience in any way? What is your interpretation of the way her face ‘rustles where it lands’ in the last line? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Thank you!

The only reference you make to an anti Muslim person is Trump. How typical. Successive American presidents have murdered, starved, injured and displaced millions of Muslims in their native countries. Closer to home Britain’s colonial heart is beating strongly with its current bombing of Yemen and it’s support and aid for genocide in Palestine.

Hi Michael,

Thanks for your comment, although I’m not sure what to make of it. The reference in question was to the Muslim flight ban, which seems more than apposite to this poem, set as it is at an airport immigration counter. I do provide links to other examples of rising Islamophobia in a general sense, including one to an article about institutional discrimination in airport security training. I state that Islamophobia is on the rise around the world, and then conduct my analysis of themes of identity raised by the poem. While I don’t disagree with your assertions, I’m not sure how far I can go into the specifics you raise in a poetry analysis. I’ve tried to cleave close to the poem, particularly in light of the author’s lived experiences and the images she’s provided.

I’m grateful for your reminder that, sadly, it seems no matter when the poem is read and how much time passes, the phrase These Are The Times We Live In seems ever more pointed and relevant. Sad times indeed.

This was such an insighful and well-written analysis of the poem, thank you so much.

Thank you for your kind comment, Fanfan. I’m so glad you enjoyed the analysis.

Nice drawings, they supply a lot towards the meaning of the poem