Robert Hayden’s heartbreaking song of ice and fire.

“His work… gives his imagination wings, allows him to travel throughout human nature.”

Lewis Turco, Michigan Quarterly Review

Older readers may have to think back a way; younger readers I bet can easily relate; if you’ve got children yourself I guarantee you’ll recognise the relationship in today’s poem by Robert Hayden. Be honest – everyone, at some point, doesn’t appreciate their parents enough. Even the saintliest child occasionally moans and complains about mum and dad being embarrassing, not loving us enough, not getting us, and the like. Robert Hayden’s speaker was guilty of this; he admits to speaking indifferently and never thanked his father for his quiet attentions. The speaker has, belatedly, come to realise the unspoken love behind his father’s small, everyday actions; this poem can be seen as his effort at reconciliation, a poignant admission of his earlier mistakes.

Sundays too my father got up early and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold, then with cracked hands that ached from labor in the weekday weather made banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him. I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking. When the rooms were warm, he’d call, and slowly I would rise and dress fearing the chronic angers of that house, Speaking indifferently to him, who had driven out the cold and polished my good shoes as well. What did I know, what did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices?

The central image in the poem is of his father rising early in the cold winter mornings – Sundays too implies he does this every day – and stoking a fire to warm the house while his son still sleeps. It’s a lovely gesture, symbolic of a father’s gentle warmth and love. The poem acknowledges the father’s stoicism in the face of hardship: his cracked hands that ached from labor in the weekday don’t keep him from this small act of kindness. Typically, it goes unappreciated by his petulant son. The word ‘love’ isn’t spoken in the poem until the final line, but throughout it simmers under the surface like glowing embers in a smouldering fireplace. Hayden’s poem neatly illustrates the truth of the old aphorism: ‘actions speak louder than words.’

It’s easy for the reader to associate fire with love. The symbolism is well-worn; love is ‘hot like the sun,’ or warm like an evening fire. Passion can be ‘fiery,’ ‘blood can burn.’ The list goes on, so much so that using fire as a metaphor for love risks being cliché. We use the word ‘frigid’ to describe somebody who doesn’t seem to feel passion, and speak of love melting somebody’s ‘frozen heart.’ Some of these associations are at play in Hayden’s poem, although they are muted; appropriate for the unspoken love a gruff father displays for his family. It’s there if you look carefully enough (something the speaker wishes he had been able to do). The comfort love can bring is expressed through warm; consistency and reliability through Sundays too; the resolve of someone who is quiet yet insistent is there in he’d call. The relatability of the symbolism actually strengthens Hayden’s poem; the emotion it conveys is universal. Twice love rages: banked fire blaze and driven out the cold. These moments convey the transformational power of small, loving gestures and are all the more effective because they are so rare. If you have a withdrawn, stoic father who can nevertheless stand his ground when it matters, you should be able to recognise this figure in Hayden’s poem.

Maybe the frostiness in the house is not all the child’s fault. I get the feeling that the father was a difficult person to get close to. His taciturn, formal character is strongly implied through form: the deliberate arrangement of lines into stanzas evokes a formality just by looking at the page. The diction of the poem (with notable exceptions) is spare, almost undecorated. On three occasions Hayden employs hendiadys (the linking of two related words using ‘and’): in both wake and hear, rise and dress, hendiadys evokes the formality of the family’s morning ritual. Everything the father does is mannerly and considered. Polishing good shoes (another symbol of formality), stoking a fire, the morning wake-up call – so formal are his actions and interactions, you might be forgiven for thinking he was a servant or butler. The description of the fire as banked means to be covered in coal dust, a practice that meant the fire would burn longer, and that happily also provides a visual metaphor suggesting his father is capable of feeling great love, but keeps it hidden behind other aspects of his austere character.

The father’s austerity is suggested also by poetic form. Quickly count the total number of lines in the poem – fourteen lines indicates the poem is a sonnet. But, apart from the subject matter (there is a long literary context of sonnets being written about love) not much else really fulfils the expectations of the sonnet form. At the very least a sonnet should be written in iambic pentameter and have a rhyme scheme; Hayden’s poem isn’t rhymed and, at first glance, doesn’t scan easily into iambs. Let’s look more closely at the first stanza, though, this time with accents marked:

Sūndays/ tōo my/ fāther/ gōt up/ ēarly/

and pūt/ his clōthes/ on īn/ the blūe/ black cōld,/

then wīth/ cracked hānds/ that āched/

from lā/ bor īn/ the wēek/ day wēa/ ther māde/

bānked/ fīres/ blāze./ Nō one/ ēver/ thānked him./

Like the father – who keeps his emotions hidden under a layer of inscrutable stiffness – Hayden’s sonnet only occasionally allows its true form to emerge. The rhythm (meter) is a case in point. The opening line is pointedly not iambic. As you can see, each and every foot is reversed (a stressed-unstressed foot is called a trochee – pronounced ‘trocky’). Lines two and four are recognisable as iambic pentameter; the third line is truncated. In the final line Hayden arranges three stressed syllables in a row: bānked/ fīres/ blāze./ At the moment of lighting the fire, the pattern of stresses perfectly conveys the deep well of emotion that the young version of the speaker failed to recognise, contained in this selfless gesture. And what about rhyme? It’s unarguable that there’s no rhyme scheme – but that doesn’t stop the occasional internal rhyme from creeping in: black/cracked and banked/thanked are subtle nods towards the sonnet’s conventional requirement for rhyme.

Having discussed fire, we should also appreciate Hayden’s use of cold as an opposite but equal symbol. The winter setting defines the atmosphere of the house and also expresses different aspects of love: for example, bitterness; the rancour that can come from living together in close confines; tension that comes from miscommunication. There is a connection between the frosty atmosphere of the house (cold is repeated three times: blueblack cold, cold splintering and driven out the cold) and the reserved, austere personality of the father. At times, Hayden uses cold as a symbol for the way it can be hard to display love and affection, especially considering the way a man in early 20th century America might be expected to behave towards his son. As you can see from the last lines of the poem, it’s easy to misinterpret: our speaker asks, what did I know of love’s… lonely offices? Above all though, we can recognise the devotion of a father who everyday suffers the cold alone so his son doesn’t have to.

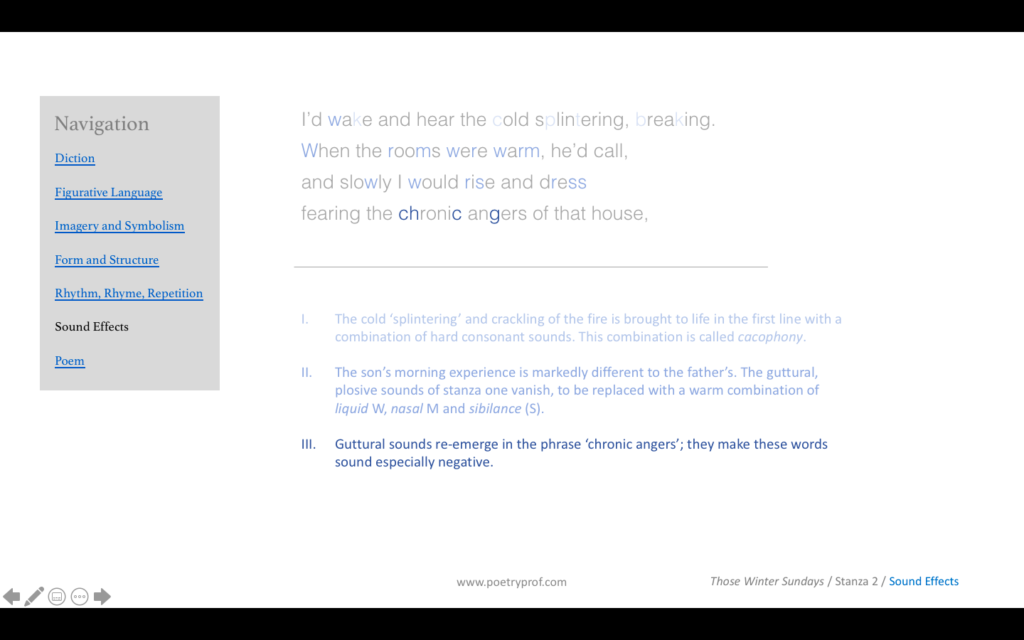

In order to see this most clearly it is worth comparing and contrasting the father’s morning experience in stanza one with that of the son in stanza two. Take the simple actions of my father got up and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold. The combination of plosive (P), guttural (hard C) and even dental (D and T) is potent. All three are good at evoking negative feelings – mixed together they make even these few simple actions sound unbearably hard for an old man suffering chronic pain in his fingers. Now take a look at the son’s lines:

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress

All those hard sounds have vanished, to be replaced with soft, warm W alliteration (when, warm, slowly, would) and sibilance (slowly, rise and dress). The combination helps each sound reinforce the other. Together they are warm and fuzzy, illustrating how much the father’s small actions make the scene more comfortable for his son. The message couldn’t be clearer: he suffers so his son doesn’t have to.

In all honesty, all the other poetic features of the poem pale beside Hayden’s manipulation of sound. Think of two things before you reread the poem. One: huddling round a bonfire late at night and hearing it spit and crack and sizzle in the dark. Two: putting ice cubes straight from the freezer into a glass of tepid water and hearing them splinter and crack. Once you’ve done this, read the poem out loud again. Do you hear it sparkling and crackling like flames on a cold, dark morning? Do you hear the sharp crack of ice splitting apart? Hayden’s poem is a masterclass in how to let the natural sounds of carefully chosen words energise a scene. The secret is in the guttural C, K or CK alliteration that spits off the page like flames darting into the night. Take a deep breath, here we go: blueblack cold; cracked; ached; weekday; banked; thanked; wake; cold; breaking; call; chronic; speaking; and a final cold. As well as summoning images of fire and cracking ice, this sound links to his father’s cracked hands through association with sharp pain, and even faintly evokes the ‘fractured’ relationship between father and son. There are other sounds at work here too, often plosive, that combine with guttural to intensify the effect. I’m sure you picked out alliterative pairs such as blueblack, weekday weather, banked/blaze.

“the chronic angers of that house.”

Although the father is the nominal subject of the poem, the speaker’s own personality comes across strongly too. He appears something of an ingrate, not least when he tells us bluntly, no one ever thanked him, and speaking indifferently. It’s like he felt his father was below him, not worth any attention. Did the speaker look down on his father, feel he was ‘below him’ in some way? Cracked hands that ached and labor in the weekday tell us he was a manual labourer. Form plays it’s part here. Ask yourself why the poem is unrhymed, and consider what that suggests about the distance between the two. There’s definitely some unspoken anger between father and son, and the word chronic means ‘incurable’: it was never resolved. There is a clue in the last word of the poem: offices. Years ago, ‘offices’ was much closer in meaning to the word ‘duties’ than it is today. A little information about Hayden’s life might throw some light on this choice of word: his biological parents separated before his birth in Detroit in 1913 and he was brought up largely in foster care. His biography describes his home life as ‘tumultuous,’ reproduced here in the phrase chronic angers of that house. Offices suggests he used to feel his parents brought him up more out of duty than love. It’s normally a mistake to assume the speaker of a poem is the same person as the writer, but there is probably more than a little of Robert Hayden’s true life experience in Those Winter Sundays. It’s easy to see how, years later, Hayden might look back on these times through older, wiser eyes and understand the stoking of the fire as a small gesture containing all the unspoken love that his father couldn’t say aloud.

Redemption and reconciliation come movingly at the end when he asks repeatedly (a nice touch strongly conveying the depth of his regret): What did I know, what did I know? We understand that he finally understands. But… did you notice the disappearance of all those guttural sounds – the fire provided by his father – from the last two lines? The inference is clear; the chance has gone. The powerful sadness of this poem comes from our realisation that the love between the two always remained unspoken and unrecognised… until it was too late.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- My Papa’s Waltz by Theodore Roethke

Remember standing on your dad’s feet and ‘dancing’ around the kitchen? In this poem, Roethke looks back at his relationship with his father, expressed in the way they danced together late at night before bedtime.

- Elegy for my Father’s Father by James K. Baxter

This wonderful poem presents another taciturn father figure who, despite his reserved and formal character, possessed a bright and vivid inner life.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Those Winter Sundays at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed the analysis and would like to discover more, you could download a bespoke study bundle for this poem. Costing only £2, you can find the bundle for Those Winter Sundays – and lots more poems – in the shop. The resources include:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on the way Robert Hayden employs alliteration and consonance to create effects in the poem.

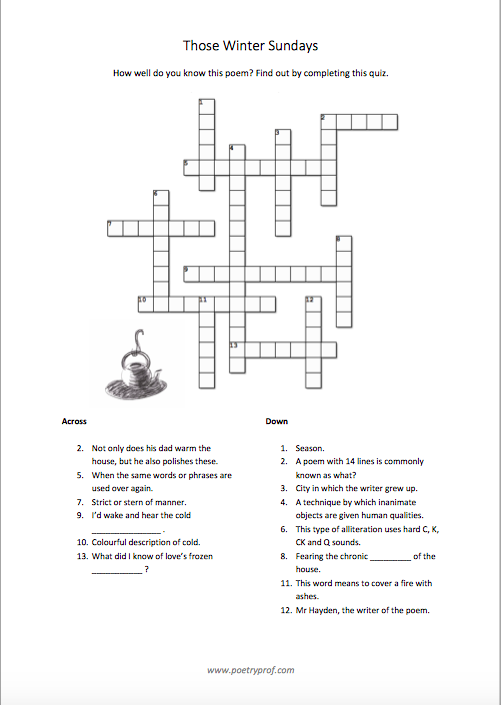

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap activity or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

How did you respond to Those Winter Sundays? Were you moved by the ending or did the poem leave you cold? What sounds did you hear when you read the poem for yourself? Leave a comment and let other readers know what you think. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Thank you!

Glad you like the blog, Diane. Hope to see you on some of our other pages soon.

is a proseprof.com a work in progress 😅

also is there material on the poem ode on melancholy

thanks

And also ‘cetacean’ and in ‘praise of creation’ would be great help

Hi Nakshh,

I’m actually working on Cetacean now. As you can imagine, each poem takes a while. I hope to have it up in the next couple of weeks. As for the other two poems you mentioned, hopefully I’ll be getting around to them at some point soon. Watch this space!

Hi Nakshh,

That’s a brilliant idea! Unfortunately, Poetryprof has only just started and it is already more than enough to keep me busy. Perhaps when I retire… but that’s a long way off yet.

I’m glad you like the blog. See you on some of our other pages soon.

Hey Mr. Poetryprof,

I dont know if you are gonna read this but damn, your analysis on these poems are super detailed and insightful. They are really helpful for my igcses. Just wanted to take a moment to appreciate your quality, top-notch analyses for completely free and no ads.

Hey Mr Boi,

Thank you for your kind words. I’m really happy you enjoy the blogs, and hope they continue to be helpful to you. Best of luck with your studies!

Just a quick comment to point out that in your Those Winter Sundays resources the final line is incorrect.

Songs of Ourselves (and other sources) have the following for the final two lines of the poem:

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

Your powerpoint says : austere and frozen offices.

Hi Tara,

Thank you for your comment. You’re right – I’ve made the change so the final line now reads ‘austere and lonely offices’ in the PPT presentation.

Thanks again!