Go with John Keats on a quest to find Joy in the mystical realm of Lethe.

“Here lies One Who’s Name was writ in Water.”

Inscription on John Keats’ gravestone in Rome, dated Feb 24th 1821

John Keats was no stranger to suffering. Although his early childhood was ordinary, and his parents had high aspirations for their clever son (they wanted to send him to Harrow), in April 1804 his father fell from a horse and died, plunging his family into a life of insecurity and worry. Keats’ mother Frances remarried a man called William Rawlings, but this decision would turn out to be a disaster. She lost some part of her inheritance from her first husband to him and soon left the family to (possibly) live with another man. She returned a broken woman, body wracked with tuberculosis, a disease from which she died in March 1809. From this moment Keats became the oldest male member of his family and would continue to do his best by his younger brothers and sister until the end of his tragically short life (Keats died either from tuberculosis – the awful scourge of his family that also took his mother, uncle and younger brother – or from the inadequate and harmful medical treatments of the time, at the age of only 25). As well as his personal experience of suffering, until 1816 he trained as a surgeon – setting bones, treating infectious diseases and performing bloody operations – in a time before modern painkillers and antiseptics. Given the scenes he must have witnessed at Guy’s Hospital (where he trained until 1816) no wonder he was inspired to write Ode on Melancholy; a poem contemplating, not only the presence of, but the supremacy of sadness in the world:

No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf's-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kiss'd

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow's mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine;

His soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

Keats’ poetry is perhaps most famous for a sequence of odes he composed between 1817 and 1819, of which today’s poem is one. An ode is a lyrical poem (meaning it has rhythm and a rhyme scheme) addressed to a person, object (such as Ode to a Grecian Urn written in 1817) or an abstract idea (such as Melancholy, the subject of our poem today). Even before he wrote Ode on Melancholy in 1819, Keats observed what he believed was a paradox of happiness and sadness; he thought that people cannot experience true joy without joy turning to sadness. In On Seeing the Elgin Marbles he complains that his spirit is too weak and that mortality weighs heavily… like unwilling sleep. In Ode to a Nightingale he cries that youth grows pale… and dies. In other odes (to Psyche, Autumn and Indolence) ghosts, phantoms, shadows and faded figures stalk the stanzas and beauty inevitably falls into decay.

You can find the genesis of Ode on Melancholy’s central conceit (a conceit is a kind of extended metaphor that contains the most important idea of a poem) – the metaphor of mortals questing for an illusory ideal, such as Joy, Pleasure or Delight – in Keats’ epic narrative poem Endymion, the composition of which would dog him for many years. While writing Endymion he suffered frequent mental blockages and long months of futility stuck at his writing desk; so, he came to believe that redemption and ‘transcendence’ would only come through suffering. You can see (and hear) this theme at play in Ode on Melancholy through the interlocking of Joy and Despair. Keats posits that one cannot exist without the other, as encapsulated in the symbol of a temple to Delight that actually contains a shrine to sadness and Melancholy as well. The meter of an ode is iambic pentameter and, in this particular ode, the repeated unstressed-stressed rhythm suits the idea of journeying or questing to find happiness very well indeed.

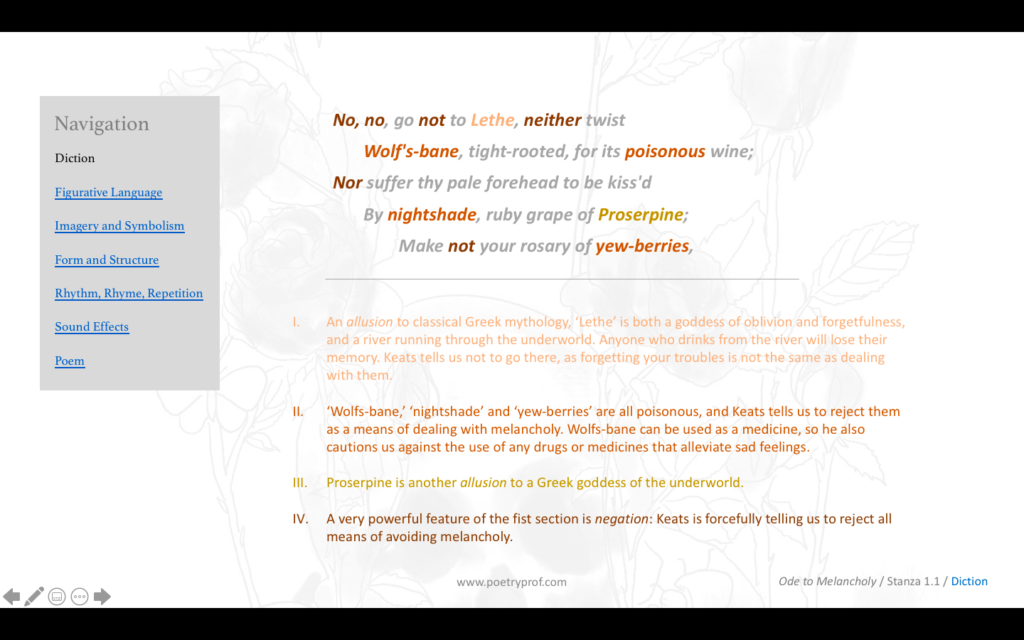

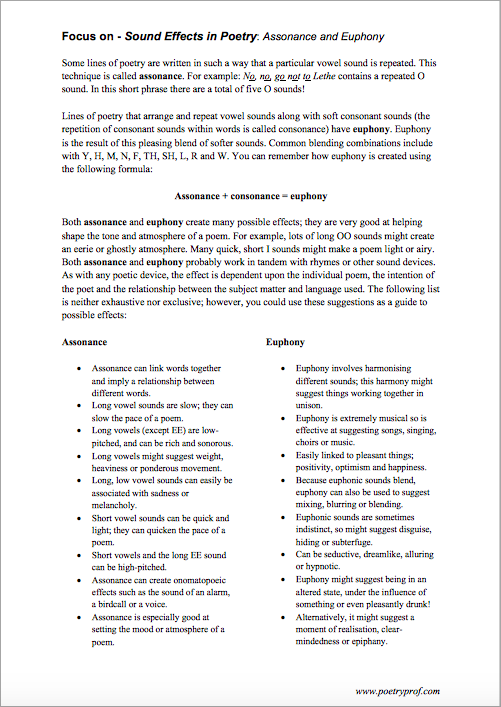

The poem begins with this imaginary quest to find the temple of Joy in the mystical realm of Lethe – a quest that depends on you not succumbing to the temptation to consume something that will ease your melancholy. Lethe (pronounced Lee-thee) is a classical allusion to a goddess of oblivion and forgetfulness, and also one of the five rivers of Hades. Anyone who drank from the river would lose their memory and even listening to the sound of the river would be enough to put you to sleep. Keats’ recreates Lethe as a kind of fantasy realm, a place where forgetfulness resides; ‘going to Lethe’ becomes a metaphor for consuming things to take the edge off feelings of misery – and the first line practically screams not to go there: no, no, go not to Lethe, an appeal strengthened by assonance (look at all those O sounds in the first and second lines (wolfs-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine). It feels to me that the Lethe of Keats’ imagination is a river surrounded by an overgrown forest, bristling with dangerous plants and animals that are all out to get you. Wolfs-bane, like yew-berries and nightshade, are poison plants that the speaker fears will be made into things that can ensnare, trip, entwine or trick you: Wolfs-bane can be squeezed into wine to make a potion that will dull the mind; yew-berries made into rosary beads (in other words disguise themselves as something they are not); your forehead can be kiss’d (touched) by deadly nightshade. He begs the listener (referred to, unnervingly, as you) not to twist these poisons out. An obsession with ‘consuming, eating and drinking’ runs through the entire poem: in this stanza you’ll find wine, grape and various berries; in the next you’ll be told to glut and feed; finally a strenuous tongue gets to burst Joy’s grape against a palate fine – only to find the taste of sadness hidden inside.

Back to the first stanza, and you’ll hear Keats’ strong exhortations unroll in a fever dream of images, symbols and allusions. Keats names something in the realm of Lethe, something which symbolises taking some kind of medication, intoxicating drink or drug in order to forget suffering – and warns you to avoid it. There are swarms of carrion beetles and death-moths living there, so he warns you against making them your mournful Psyche – in other words, don’t let them burrow into your mind. There’s a downy owl (assonance again, working to align the owl with the forces of drowsiness) who sits malevolently watching, waiting to be a partner in your sorrow. So don’t let him see you. For every danger in Lethe, find the imperative verb (used to give commands) and its negation: go not, neither twist, make not, suffer not, nor let. Keats pleads with you not to allow yourself to succumb to the temptations of Lethe in whatever guise they might take.

At the end of the first stanza Keats tells you why you should not seek out oblivion, and the reason is quite surprising. It’s not because he wants you to live a life free from sadness. Keats doesn’t believe this is possible. Instead, he believes oblivion will come to you anyway, so there is no need to seek it out. He says:

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

It becomes clear that Keats sees our day-to-day lives as miserable (waking anguish) and only through the final oblivion of death (a shade is a spectre or ghost of one who has died) will there be any relief from the world’s troubles. Those who believe they can avoid this waking anguish (or live a life free from sadness) by questing into Lethe, Keats says, are mistaken. All they will find in this realm is a false oblivion. While he delivers these lines he employs thick sibilance (a kind of alliteration using S or SH sounds: shade to shade, drowsily, anguish, soul) and blends words with similar sound patterns (drowsily and drown are clear examples) creating a dreamlike, woozy atmosphere which suggests the temptations of Lethe are seductive – or even mimics the kind of blurry, soft happiness one might feel under the influence of strong medication.

The second stanza develops the idea that sadness itself, described here as a melancholy fit, is something that can’t be avoided. It spreads in a weeping cloud, covering the world (hides the green hills in an April shroud) and polluting (fosters the droop-headed flower) the landscape. He employs oxymorons (droop/flowers; April/shroud) to suggest both the way happiness can suddenly be overcome with sadness, and to express his opinion that happiness and sadness co-exist. Shroud is a white cloth that is used to wrap corpses for burial, a word that sits uneasily alongside April with all its associations of new life and vitality. By now Keats has painted a picture of the world shrouded in, infected by, covered by or drowning in sadness. It seems that whichever way one turns, or whatever one does, sadness is inescapable. Once he’s established his cynical and pessimistic vision, though, Keats gives us some advice as to how we can cope with living in a world so sad. (If you’re finding his argument hard to follow, look closely at the punctuation and connectives he uses in the second stanza. He uses simple signal words to stage out his argument: But introduces the descriptions of the melancholic fog; a semi-colon at the end of line 4 marks the end of this description; then introduces his advice in line 5.)

Now Keats doubles down on his message; that there is no point in trying to escape sadness as it will find you in the end anyway. Instead of wallowing in sadness or forgetfulness, he advises you to fixate on beautiful things, such as flowers and rainbows and even the deep, mysterious eyes of a lover as one might glut (meaning to feast greedily) when one is hungry. And herein lies the paradox at the heart of the poem. Keats associates Joy with Beauty, which is transient – beauty, in whatever form he finds it, be it flowers or rainbows or whatever – inevitably fades, taking joy with it and leaving sadness in its place. As a result, you need not invite melancholy eagerly into your home, but you cannot shut the door and lock it outside either. When looking at flowers and rainbows one knows that they will disappear soon, so pleasure is always tinged with sadness. The transience of these images (the rose is only a morning rose; the rainbow appears as a wave of salt and sand) creates a sense of urgency: it’s like somebody who receives a terminal diagnosis and, throwing their hands up in the air, says, ‘if I have to go, I might as well make the most of life while I still can.’ Remember, Keats’ life was blighted by tuberculosis, and he wrote this poem just after the death of his brother Tom, so his fatalism may not be unearned.

It’s worth dwelling for a moment on the final image Keats gives us in stanza 2; that of staring deep into a lovers’ eyes as she shouts at you in anger! He says to ignore her incoherent words (suggested by his use of the word rave) and simply to take her hand instead. (He uses the word Emprison for this, suggesting being ‘trapped’ by the reality of a world in which there is no escape from sadness.) I don’t know about you, but I think this is absolutely brilliant advice, and something I’m going to try next time my girlfriend loses her temper. The presentation of this advice involves both the visual and auditory fields of perception. Assonance is particularly effective, the long EE sounds in feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes seem to engulf, envelop and seduce – even as your lover angrily raves away. It’s like a movie image in which the camera focuses ever more closely on the eyes and the director begins to mute the sounds of the scene until they blend together and fade into the background. This image is the high point of the poem for me – in a single moment it expresses all the ideas we’ve discussed so far: the co-existence of joy and despair; why you don’t need to quest after melancholy as it will come to you anyway; the way we should accept unpleasant things as an inevitable part of life.

The third stanza brings us to the end of our journey to find illusory ideals such as Joy, Beauty, Pleasure and Delight and explains, explicitly this time, why the quest is doomed to fail: She dwells with Beauty – beauty that must die. As your lovely young mistress will eventually grow old and die, so too, Keats tells us, Joy and Delight et al are mortal and will always succumb to age and time. These abstract ideals are all capitalized, which helps personify them and gives them the ability to die. The word dwell is part of the personification, as if happiness lives with, and is dependent upon, Beauty; so too is Joy able to speak, Bidding adieu or ‘saying goodbye,’ and Pleasure can feel pain. Keats is telling us not to pin our hopes for happiness on something as transient as Beauty, which dies, or something as fleeting as Joy, who always leaves. Once again, this seems like good advice.

One thing you definitely shouldn’t ignore is how Joy’s oppositions (Melancholy and Despair) are capitalized too, and thereby personified themselves. Surely that must mean that all those negative emotions too will eventually fade away? Well… yes, exactly. Just as beauty is certain to fade and joy inevitably turns to despair, melancholy is equally impermanent. Keats reinforces the relationship between opposite emotional states through oxymoron (aching Pleasure) juxtaposition (beauty/die, Joy/adieu, Pleasure/poison) and alliteration (Pleasure/poison). Once again, assonance plays a larger role than you might think, the sounds of these words repeat and blend to the point of being near-rhymes (see beauty/adieu) and erase distinctions between happy and sad states of being. This is actually quite a comforting thought and brings balance to what otherwise might be a relentlessly bleak world view.

This is the crux of Keats’ philosophy: all human ideals are illusory, so the quest to find any one of them (like Joy) is a futile one. We are earthly, mortal creatures unsuited for questing in mystical realms like Lethe. This belief pervades much of Keats’ poetry; On Seeing the Elgin Marbles locates beauty in a concrete object firmly belonging to this world, not a fantastical, make-believe realm. He told us in the first line of Ode on Melancholy: no, no, go not to Lethe. Now we understand why. Even if you succeed in your quest and discover the hidden temple of Delight, inside you’ll find a sovran shrine to Melancholy squatting there instead. The word sovran is an archaic form of ‘sovereign’ or ‘supreme’ – the use of this word suggests that, like a devious tyrant pulling the strings of a puppet king, Melancholy is the true ruler of this realm. It’s a fitting discovery to end a foolhardy quest.

But Keats believes in the need for keen vision to see the presence of Melancholy in the temple (look how she is veil’d meaning ‘hidden’ or ‘disguised’). So, he finishes his poem with a simple image of a man eating a grape that looks like Joy, but tastes of sadness. I find it interesting that his mode of address has changed in the third stanza, from you to him (though seen of none save him) as if Keats doesn’t believe you, dear reader, are the one who is perceptive enough to see the sadness hiding at the heart of joyful things, like grapes:

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine;

His soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

Unlike you, this person is strong of will (strenuous) and has a refined sensibility (palate fine) – enough to accept the truth of Keats’ philosophy. He can burst Joy’s grape against the roof of his mouth and is able to taste the sadness that was hiding inside. The grape symbolises and summarises the entire conceit of the poem: that always inside Joy lurks sadness. Whoever consumes this grape is rewarded both with the knowledge that Joy and sadness always co-exist in the world – and with a place for his soul among the trophies hung on the temple’s wall. This is a dubious accolade at best, and you might be entitled to ask whether the reward for accepting a world full of inescapable misery might not be something a little more forgiving.

But then, what did you expect from a poem entitled Ode on Melancholy?

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Ode to Autumn by John Keats

Part of his famous sequence of odes (written in August and September, 1819), you can find all the same technical devices (such as rhythm and rhyme) put to the subject of Autumn.

- The Moon and the Yew Tree by Sylvia Plath

This poem shares a symbol with Keats’ Ode on Melancholy – the yew tree, a symbol both of her own melancholy and also of her mother. In Plath’s poem the black, Gothic branches of the tree send her messages only of ‘blackness and silence’.

- Lucky Life by Gerald Stern

This fantastic poem is like a modern day counterpoint to Keats’ more traditional ode on sadness. Stern contemplates life and all it’s misfortunes, crises and little moments of happiness; at one point he describes two statues of Christopher Columbus, one hunched and pained, the other proudly guiding the way. As a symbol for the way joy and melancholy intertwine in our lives, you couldn’t really ask for much clearer.

- Alone by Edgar Allen Poe

Like Keats, Poe would suffer a loss (his mother) just a month before writing this poem. Like Keats, Poe would die tragically before his time. Like Keats, he finds inspiration in the more melancholy side of life.

Additional Resources:

If you are teaching or studying Ode on Melancholy at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining assonance and euphony in Keats’ poem.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Ode on Melancholy? Do you agree that sadness and Joy are inextricably linked? Which is your favourite of Keats’ images? Why not share your thoughts, add an idea or ask a question in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Wow what a great analysis! Thank you!!

Hi Johnny, glad you like the commentary.

This is too good!! The depth of your analysis always intrigues me research deeper!! Thanks a million!!

Hi,

Thank you for your kind comment. I’m really happy you enjoy reading my analysis. Hope to see you again on some of the other posts.

Wow, this is amazing! What a depth of analysis!

Thanks a bunch

Hello Mr Prospect,

Thank you for your kind words. Keats wrote so evocatively and richly – there is so much to analyse! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Wow this was such a great analysis you really opened my eyes to the depth of this poem!!