Faith is stronger than doubt in this eulogy by Elizabeth Jennings.

“Jennings is a woman who can write a really glowing line…”

Sandra M. Gilbert (Poetry Magazine, 1987)

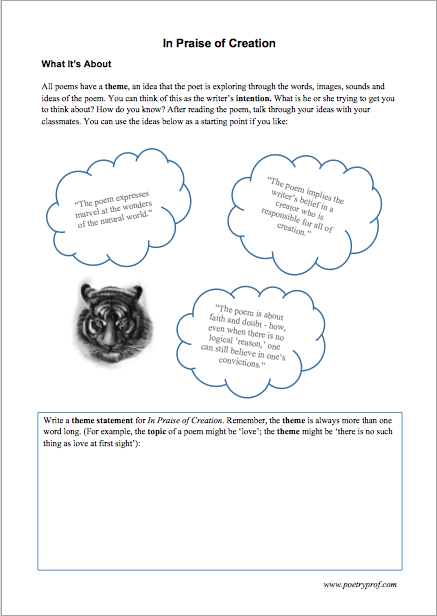

Sometimes in these blogs I caution the reader not to automatically equate the speaker of a poem with the voice of the poet herself. Today, I think we can confidently make an exception. Elizabeth Jennings was a devout Roman Catholic and In Praise of Creation sits comfortably alongside several of her other works in expressing her religious convictions. The poem explores the idea of having faith, and expresses Jennings’ belief that, despite leaving no direct evidence of his existence, God is responsible for the miracles of nature Jennings sees in the world:

That one bird, one star,

The one flash of the tiger’s eye

Purely assert what they are,

Without ceremony testify.

Testify to order, to rule –

How the birds mate at one time only,

How the sky is, for a certain time, full

Of birds, the moon sometimes cut thinly.

And the tiger wrapped in the cage of his skin,

Watchful over creation, rests

For the blood to pound, the drums to begin,

Till the tigress’ shadow casts

A darkness over him, a passion, a scent,

The world goes turning, turning, the season

Sieves earth to its one sure element

And the blood beats beyond reason.

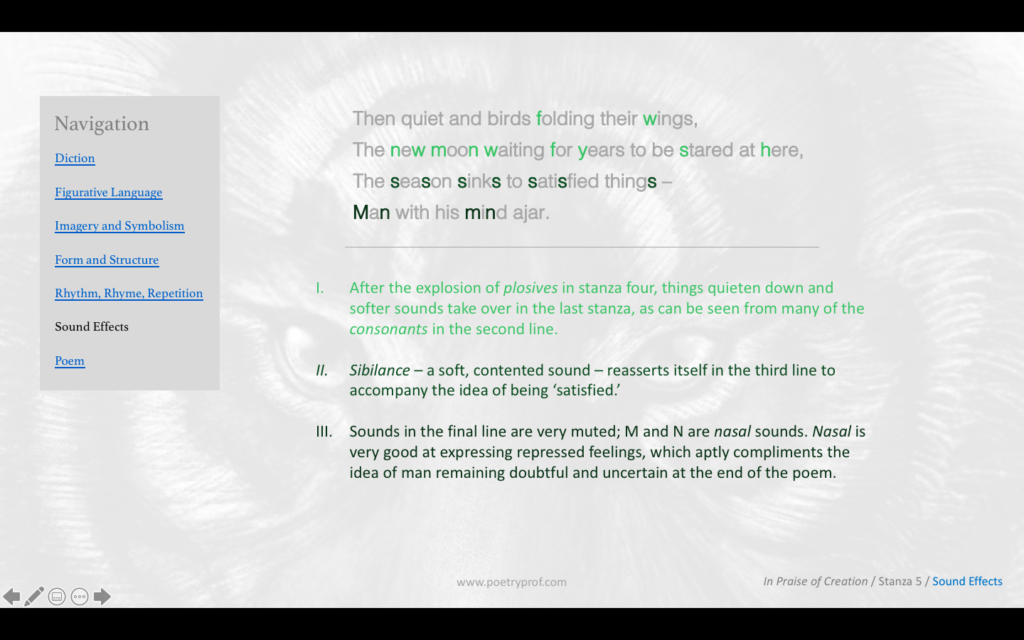

Then quiet and birds folding their wings,

The new moon waiting for years to be stared at here,

The season sinks to satisfied things –

Man with his mind ajar.

Before we look at today’s poem more closely, it might help to take a quick look at some of Jennings’ other works. In A Garden presents the metaphor of a garden abandoned by the gardener, which could hardly be more explicit in dealing with the idea that God created the world:

When the gardener has gone this garden

Looks wistful and seems waiting an event.

It is so spruce, a metaphor of Eden

And even more so since the gardener went.

Another poem, Absence, wrestles with the same dilemma; God exists in the speaker’s thoughts but there is no actual evidence of his presence in the world:

It was because the place was just the same

That made your absence seem a savage force,

For under all the gentleness there came

An earthquake tremor: Fountain, birds and grass

Were shaken by my thinking of your name.

In Praise of Creation offers a resolution to this dilemma: nature itself asserts the existence of God. Through her observations of aspects of the natural world (a bird, a star and the flash of a tiger’s eye), Jennings locates an intelligent design that, like the flowers in a garden that continue to bloom after the gardener has gone, stands as proof of God’s hand at work. Words such as testify, assert and without ceremony convey Jennings’ sense of certainty and resolute belief: testify means ‘declare proof of existence’ and assert means to ‘confidently state a belief.’ Diction like this is more at home in a courtroom than a poem; employed here it is as if Jennings is putting the existence of God on trial. But, like a clever defence lawyer, she tells us that she doesn’t need to argue a case on his behalf. Birds or tigers or stars validate her religious faith simply by existing; they don’t need reason to explain them.

In this way, In Praise of Creation is a kind of eulogy, a poem of praise. Eulogies are often pressed into the service of praising God, but this time God’s name is not actually in the poem – just as you can’t find concrete evidence of God’s existence in the world. Herein lies the crux of Jennings’ ‘defence’: Creation itself is proof enough, needing no further elaboration. Even the use of this word in the title implies the existence of a ‘creator.’ Jennings casts her eye around and is able to discern things clearly: that one bird, one star, The one flash of the tiger’s eye. Her use of language reflects the strength of her belief: simple, straightforward phrases, monosyllabic diction (meaning most words have only one syllable) without ambiguity. She repeats one, one, one, and refers to that and the; these elements of sentence structure helps me imagine Jennings looking here, then there, picking out details from the whole panorama of creation available to her. And, all in all, she sounds content with things she sees around her.

That’s not to say faith is unassailable: a tension between ‘faith’ in God and the need for proof of God’s existence (labelled reason here) runs through the entire poem. It is most strongly located in the symbol of the tiger. At one point, the tiger is described like an all-powerful God watchful over creation. But then, quite suddenly, he is described as being wrapped in the cage of his skin, an image that suggests he can be caught or trapped – not very godlike at all! Too, the tigress’ shadow casts a darkness over him, which is surely a metaphor for the way faith can be tested. The climax of the poem in the fourth stanza can be read as a battle between ‘faith’ and the forces of reason that might cause one to ‘doubt’. The triumph of faith is celebrated when the season sieves earth to one sure element; another metaphor conveying the idea that faith becomes stronger through testing and adversity, as one might temper metal through heating and beating. The image of ‘sieving’ suggests passing beliefs – reason, doubt, faith and so on – through a filter that removes everything but one sure element: ‘faith’. Only once this process is complete can the world quiet and the birds fold their wings, images suggesting the settling of doubt and the calming of disturbances to the ‘natural order’. I find the idea that faith is not unassailable, and Jennings’ admission that it can be tested, assaulted, and doubted, brings balance to a poem that otherwise might sound a bit preachy.

If Jennings herself is so sure of God’s presence, then where does doubt come from? In a world where people only believe what they see, man finds it hard to remain faithful to God when – to borrow the metaphor from Absence – the gardener has left the garden. While everything else sinks to satisfied things, man stands apart from nature, unable to resolve his doubts because of his reliance on reason to understand the world:

The season sinks to satisfied things –

Man with his mind ajar.

In the final line, man’s mind is ajar, a word that connotes being out of sync with Jennings’ belief, and therefore unable to fully appreciate the miracle of creation. The use of this word also conjures an image of a door standing half-open with man at the threshold reluctant to pass through. It’s no accident that Man doesn’t appear until the last line, and even then, he is still detached from the rest of the poem by a hyphen. His ‘separateness’ is further suggested by a half-rhyme, here/ajar, in which the sounds don’t quite fit together. Notice too that the last line of the poem has no verb– man seems paralysed by reason and unable to pass through that door and participate in either the poem or the world God created. In this way he stands in stark opposition to birds and stars and tigers who assert their identity powerfully – being what they were created to be – rather than philosophising.

Like a masterful persuasive speech that uses both logos and pathos to convince the listener, so Jennings’ poem moves from logic in the first two stanzas to something more emotional and impassioned in stanzas three and four. Let’s go back to the start and see how the first stanza suggests that things in the universe – excluding man – get by without reason well enough. It’s not that nature is random – far from it. Jennings identifies all kinds of patterns and structures within nature: the striped pattern of a tiger’s fur; the way birds fill the sky at a certain time of day; the natural rhythms of the seasons. It’s just not a meticulous, precise kind of order; rather a loose, ‘natural order’ in which everything functions by instinct (Or as God intended) to keep the world turning. This idea of ‘loose order’ is best understood by considering the second stanza’s image of the moon sometimes cut thinly, in which a sliver of moon is visible because of the almost-but-not-quite cosmic alignment of the earth, sun and moon. Such a precise alignment, the implication goes, cannot be random or accidental. Like that metaphorical abandoned garden, there is enough pattern for Jennings to see the presence of intelligent design hidden under the surface of creation.

The stirrings of emotion – the opposite of reason – begin in the third stanza, which uses a mix of auditory and rhythmic elements to get the reader’s pulse racing: most obviously we can hear and feel blood to pound and drums to begin. Sound effects start to play a role: you can hear dental D and plosive Bs and Ps mimic the drums and pulsing blood. Enjambment, which has been quietly slipping from line to line, creates more powerful effects now, jumping the gap between stanza three and four and helping quicken the pace as we approach the climax. There’s also been a persistent euphonic UR sound that, although it runs through the whole poem, really crescendoes here. Euphony is created by mixing vowel sounds with softer consonant sounds. Right back in the first line we have a bird and a star. We’ve also got a tiger, purely, asserts, ceremony, birds, birds, certain, a tiger again, a tigress, and over – and once we’re in the passionate fourth stanza the sounds come thick and fast: over, world, turning, turning, world, earth and sure. Everything, all the poetic and technical effects are working to speed the poem up, create drama, tension, passion and emotion.

As well as being the battlefield for the conflict between faith and reason, stanza four is incredibly suggestive. A passion, a scent encourages us to imagine a mating ritual playing out – the act of Creation as practiced by creatures on earth. The sensual and intangible nature of stanza four makes me think that what drives the world and makes it go round (turning, turning) is often intangible: things like love, desire, ambition, faith are the things that motivate people the most. The emotion of stanza four is a way for Jennings to suggest that life’s most intense moments are natural, and not a result of considered reasoning. Powerful plosive alliteration in the final line not only marks the climax of the poem, but strongly suggests the beating of a passionate heart: whether it is the tigers’ blood beating in the throes of passion or Jennings’ own heart filled to bursting with the joyful certainty of God’s presence inside her is up to you to decide.

The poem may look simple – but aspects of form work together with Jennings’ choice of words to recreate the seesaw balance between reason and emotion that lies at the heart of the poem. On the side of order you have regular quatrains (a stanza of four lines is called a quatrain), an ABAB rhyme scheme, a clear overall structure. On the side of feeling and emotion there is no meter, lines shorten or lengthen whenever they feel like it, and end-stopping (use of punctuation at the end of lines) is unpredictable. Her stanzas are linked by informal methods such as enjambment and repetition: a word in one stanza is often repeated (or echoed) in another. The first stanza ends in the word testify, which is immediately picked up in the first line of the second stanza: Testify to order. The second stanza in turn uses the word full (How the sky is, for a certain time, full), which is kind-of repeated in the third stanza phrase watchful over creation. The fourth stanza repeats the word blood from the third and provides season for the fifth stanza to repeat: The season sinks to satisfied things. Birds and the moon both appear early in the poem and reappear at the end. As well, there’s just enough variation in the rhyme scheme, created by half-rhyme, to keep in tune with Jennings’ theme: that a loose ‘natural order’ was established by a gardener before he left – listen to only/thinly, rests/casts and – most clearly – here/ajar to hear how either the vowel sound or the consonant sound, but not both, concur to create these half-rhymes.

As a final thought, you don’t have to share Jennings’ religious convictions to appreciate the message of her poem. You can understand the things that Jennings’ isolates as forces of nature, for example, or a eulogy to instinctive behaviours that animals enjoy but human beings repress. Jennings was a Roman Catholic and her belief certainly provides the underlying structure of the poem – but the interpretive framework you choose to overlay on her words is up to you.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- On the Pulse of Morning by Maya Angelou

The first line of Maya Angelou’s fantastic poem shares a beat with Jennings’ In Praise of Creation – the extract on Poetry Foundation is from a much longer work, but it’s enough to give you a feeling of the similarity between the two poems.

- Pied Beauty by Gerard Manley Hopkins

One of the most famous eulogies praising God. Like Jennings, Hopkins isolates aspects of the natural world that he believes best represents God’s wonderful creativity. He particularly likes ‘pied,’ or ‘brindled things’ – that have dappled, spotted or mixed colours.

- One Flesh by Elizabeth Jennings

I like this poem because, although it’s not pursuing an overtly religious agenda, the lovely, tender descriptions of her elderly mother and father are still couched in the devout language Jennings is so good at using.

- I could suffice for Him, I knew by Emily DIckinson

At the end of this poem, Dickinson shows us an image of the tides responding to the motions of the moon; I think Jennings would have liked this image.

Additional Resources:

If you are teaching or studying In Praise of Creation at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Jennings use of stanzaic form.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of In Praise of Creation? Do you agree that the tiger and tigress symbolise faith and doubt? Are you convinced by Jennings persuasive tactics? Why not share your thoughts, add an idea or ask a question in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.