Peter Porter pushes back against consumer-culture in this uniquely un-poetic poem.

“He made me laugh, he made me think…”

Sean O’Brien, fellow poet and student of Porter.

Written in 1970, today’s poem is both a product of and critique of a capitalist, consumer society where everything is up for sale; people are consumers first and human beings second. Australian by birth, Peter Porter lived much of his life in Britain, a country that, after the end of World War Two, experienced an economic boom – shops were full of people, shelves were full of stuff, and TV screens exhorted people to buy more, more and more. Purchasing-power, shopping-malls, conspicuous-consumption was (and arguably still is) the defining culture of the day. This was the golden age of advertising and the heyday of the salesman. Increasingly sophisticated marketing techniques were developed and an entire corporate language invented: ‘brand,’ ‘cold-calling,’ ‘customer-satisfaction’ and the like. Businessmen, middle-managers, data-analysts and market researchers replaced historians and philosophers as society’s go-to experts. Men in smart suits would knock on the front door and ask buyers to fill out surveys so they could improve their products for the next year, season, or cycle. And this is where Peter Porter’s poem comes in. Having worked in the marketing industry, he was au-fait with Britain’s increasing consumer-culture outlook on life – and he didn’t like it very much. His response is the poem A Consumer Report satirising the direction society is heading by stretching the idea of consumer-culture to its very extreme: Life itself is for sale:

The name of the product I tested is Life, I have completed the form you sent me and understand my answers are confidential. I had it as a gift, I didn’t feel much while using it, in fact I think I’d like to have been more excited. It seemed gentle on the hands but left an embarrassing deposit behind. It was not economical and I have used much more than I thought (I suppose I have about half left but it’s difficult to tell) – although the instructions are fairly large there are so many of them I don’t know which to follow, especially as they seem to contradict each other. I’m not sure such a thing should be put in the way of children – It’s difficult to think of a purpose Also the price is much too high. Things are piling up so fast, after all, the world got by for a thousand million years without this, do we need it now? (Incidentally, please ask your man to stop calling me ‘the respondent’, I don’t like the sound of it.) There seems to be a lot of different labels, sizes and colours should be uniform the shape is awkward, it’s waterproof but not heat resistant, it doesn’t keep yet it’s very difficult to get rid of: whenever they make it cheaper they seem to put less in – if you say you don’t want it, then it’s delivered anyway. I’d agree it’s a popular product, it’s got into the language; people even say they’re on the side of it. Personally I think its overdone, a small thing people are ready to behave badly about. I think we should take it for granted. If it’s experts are called philosophers or market researchers or historians, we shouldn’t care. We are the consumers and the last law makers. So finally, I’d buy it. But the question of a ‘best buy’ I’d like to leave until I get the competitive product you said you’d send.

The poem’s conceit is established in the first brief verse (a conceit is like a theme; it’s the ‘big idea’ that underpins the entire poem, and is often presented as an extended metaphor): Life is just another product, designed in a boardroom, assembled in a factory, and available in a store near you. The poem’s speaker, after testing this product, is asked to fill out a customer satisfaction survey, giving his opinions and providing a rating, presumably so the designers can use his suggestions to improve future iterations. The poem consists mostly of this report, delivered in the respondent’s own words. It’s actually a really clever idea that opens up all kinds of philosophical avenues for us to wander down, such as whether we deserve the lives we get or is it all simply down to chance. For example, the speaker says that he was given his version of life as a gift and that there are actually more competitive products available. Is he simply referring to his body – as in the way some people may be born in physically better health than others – or does he mean the experiences and opportunities of the life he was given? Some people may be born to a rich family, others poor; some of us are lucky enough to be born into safe and stable societies, while others are delivered in war-times or earthquake zones. Each birth guarantees a wildly different life experience. The poem reminds us that none of us have a choice (If you say you don’t want it, then it’s delivered anyway) in where and when we are born, our genetic heritage, and who our families happen to be.

To establish his extended metaphor right off the bat, Porter sets up the poem with a little verse of only three lines that serves as a segue into the report itself. In this verse, he highjacks the language of marketing and advertising, presenting his poem in a very un-poetic register. The language is cold, dry, and uses jargon (language from a specific field is called jargon; as an industry-insider, Porter would have been more than familiar with this type of soulless marketing-speak). It feels like we’re reading from a label or a disclaimer with a ‘tick box’ at the end: The name of the product I tested is… I have completed the form… I understand my answers are confidential. The poetry is deliberately lifeless, these phrases could have been cut’n’paste from any survey of this kind. The grammatical structures are boring and even predictable: I have… I tested… I understand… are basically subject + verb + object, the most mundane and uncreative of patterns. But this is the whole point: Porter is stretching the satire to breaking point to imply that, if life itself is approached as a commercial venture, it is drained of all the fun stuff – random experiences, loves and unexpected friendships, dreams, messy emotions – that make it truly worth living. The rest of the poem features a similar linguistic drabness: for example, after defining his topic in the first verse, thereafter the speaker repeatedly uses the word it to objectify life, as if such a vast, extraordinary, and complex concept can be reduced to a single, uninteresting word.

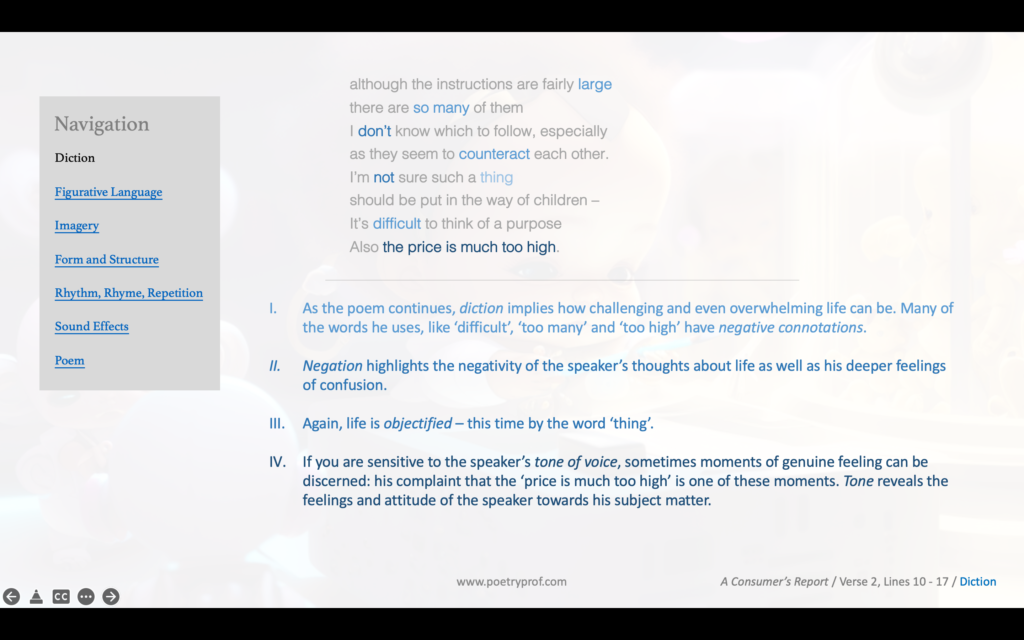

The second verse constitutes the rest of the poem and is presented in one long, unbroken column that is meant to resemble the kind of blank space on forms of this type (written in 1970, these things would always have been a physical form, not completed online). In this way the poems’ long and thin shape (also called the poem’s spatial form) represents its subject matter: a marketing survey. Porter writes in free verse, stripping his poem of rhythm and rhyme and leaving it purposely devoid of any other obvious poetic or aesthetic devices. Remember, his aim is to present language which is as mundane as possible. If life is a mere product put together on a production line, then all of life’s processes – like this report – should have the same mechanical, lifeless quality. As a response to the encroachment of corporate and consumer values into every corner of society, the satire only works if it’s as bland as this. Because the poem lacks many formal clues, there’s a challenge to following the speaker’s thoughts which are presented in something like a stream of consciousness, as if he’s filling in the form at his work desk. It’s not meant to feel crafted – whatever he happens to think of is the next comment on the report. There’s no chronological organisation, his thoughts roam backwards and forwards, bumping into one another and sparking random adjacent ideas. After all, isn’t that the way our minds work sometimes? It’s just a little glimpse that maybe we’re not all soulless-consumer-robots stuffing our faces with the next newest iPhones just yet… but more on that later. For now, you can trace the gist of his complaints because, while some lines run one into the next (using enjambment), he helpfully marks completed observations with a full stop. So, for once, you’re better off reading the lines like prose rather than poetry (again, this is intentional). As a report on Life itself, its content could encompass – well, everything! But clearly the person filling out the form can’t comment on every aspect of his life experience so far (he says I have about half left, so I’m guessing he has around forty years of accumulated experience, give or take) and we can assume he’s summarising only his main concerns.

Once he gets going patterns do appear, giving the poem some internal structure. You can divide his comments into loose ‘categories’, each of which represent deeper, more philosophical worries that we might wonder about from time to time. The first category is ‘What is life for?’ otherwise known as ‘The Meaning of Life Category.’ You can put lines such as the instructions… there are so many of them and it’s difficult to think of a purpose in this category. The extended metaphor of life being a product is so effective that almost every ‘complaint’ mirrors an existential or philosophical concern; for instance, the lack of a decent instruction booklet implies the lack of guidance in the speaker’s life, the difficulty of navigating an increasingly media-saturated environment where it’s hard to tell real from fake, good advice from bad, or even simply points to how many conflicting world views there are out there, and how to know who to listen to at any given time. His complaint that life shouldn’t be put in the way of children is humorous (everyone was a child once, it’s unavoidable!) but also points to how dangerous life can be, how easy it is to hurt oneself, or be hurt by others, or make the wrong choices when one is young. Why not pick any line and see if you can superimpose a genuine concern from your own experience, or philosophy, onto the poem in this manner. In order to convey these kinds of existential doubts in the speaker’s mind, Porter has him ask rhetorical questions like, do we need it now? He reminds us that the world has been around for a thousand million years; our modern consumer cultures, which seem so important and permanent, are merely a blink of times’ eye when thought about from this perspective. Another of his conclusions is that life is a small thing, again challenging our perception of the importance of human lives, especially when our favourite pastime seems to just be buying more and more stuff. A note of anger creeps into his report when he notes how people behave badly, accentuating this comment with plosive alliteration that is good at implying the release of negative emotion.

In the second ‘Is It Worth It?’ category he comments on the value of the product to the customer. In a pointed play on the idea that quality of life and money are inextricably bound up together, he notes: whenever they make it cheaper they seem to put less in. You can read this comment a couple of different ways; it seems to imply that some people’s lives are metaphorically ‘emptier’ than others and might make you think of the phrase ‘life is cheap’. Other comments don’t refer to the monetary value of life, it was given as a gift remember, but suggest life is costly in more metaphorical ways. Through punning on the words price and economical, he suggests one pays through upsetting, stressful or difficult life experiences, disappointments, pains, let-downs, and the like. Much of the poem is couched in diction that’s vaguely negative or worrisome: piling up so fast… so many of them… too much… it’s difficult… and so on, reveal a sense that life lived in a modern, fast-paced society is discombobulating, overwhelming and distressing. Porter’s speaker frequently uses negation (not economical… I don’t know… I’m not sure) to enhance this sense of general negativity towards and confusion about life.

‘Complaints about the Body’ is the third, and most humourous, category. Carrying each individual through a single life experience, and also the thing upon which the quality of that experience depends, the body functions as the centre of the extended metaphor in the poem; the physical aspect of the product under review is the speaker’s own body and he’s got lots to say about it’s design flaws! You can place his funny comment about bodily excretions (it… left an embarrassing deposit behind) in this category, along with it’s waterproof, but not heat resistant, which brought a smile to my face. But, when the speaker confesses it’s very difficult to get rid of, there’s the edge of something darker at play here, as if he has experienced sadness so deep that life simply hasn’t been worth living any more. He comments more than once on ageing (I have used much more than I thought… it doesn’t keep) and how, after our bodies begin to fail, we live half our lives weak and infirm. I’m not sure how i feel about his comment: the shape is awkward and sizes and colours should be uniform. It can be read as a joke and the idea that physical, racial, and other visual differences between people causes problems is up for discussion. I would argue, though, that intolerance and bigotry are the real causes of social division, rather than differences in size, shape and skin colour per se. Calling for a uniform human design would erase much of the wondrous variety that makes the world such a diverse and compelling place, and seems to run counter to the spirit of the poem. On the other hand, you can read ideas for this kind of ‘quick-fix’ to complex issues as part of the satire – it’s a solution that might appeal in a shallow society where philosophers and historians have been replaced by market research analysts.

Behind the blandness of the corporate consumer’s report is the niggling impression, though, that there’s still a living, breathing human hiding somewhere underneath. When I describe the poem as ‘lifeless’ and ‘soulless,’ I’m actually describing the atmosphere (alternatively called mood) – which is defined as the feelings the poem generates in the reader; in this case, me. Tone (or tone of voice) is different; tone is the feelings and attitude of the poet or speaker, the unnamed respondent who’s filling out the form. On the surface, whoever this person is adopts the kind of polite, reserved tone that many of us would use when interacting with an unknown administrator. That might make me feel bland and boring – but that doesn’t mean the speaker’s just a lifeless automaton. Think about when you’ve had to phone a customer service helpline, or conducted an interview, or some similar situation. The rules of polite society force us to don an inoffensive mask during such interactions. This is our speaker’s go-to mode of address – but is it a defence mechanism? As a case in point, look at how often he uses the word seem or seemed as a way of being polite about something: it seemed gentle on the hands… they seem to contradict each other… there seems to be a lot of different labels… they seem to put less in… Ironically, the more he uses polite words to cover up his disappointment, the more we can hear how upset he truly is. There’s real feeling striving to break through the superficial veneer. The same is true for the word think: I think I’d like to have been more excited… I think it’s overdone… I think we should take it for granted… Overall, he seems a little jaded, reluctant to put himself forward, like life lived in the modern world has worn him down or taught him not to be too obtrusive. In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find any positive feedback in his report; I guess, I’d agree it’s a popular product would count as positive, although it’s hardly effusive praise. Often, though, there’s a grouchy grumpiness in the speaker’s tone of voice that at least characterises him as somebody real. Until the end of the poem, at least, he’s placed in opposition to our corporate overlords, despite him saying I didn’t feel much when I was using it which, to my mind, is blatantly ironic – even untrue.

Actually, on one or two occasions, the poem offers glimpses of a genuine and vivid soul behind the report, and implies he feels things a lot more deeply than he’s letting on. Most obvious is the moment presented in brackets (or parentheses) when he breaks from compiling his report to directly address a senior company representative: (please ask your man to stop calling me ‘the respondent’, I don’t like the sound of it.) For a split second, the speaker’s polite and reserved tone threatens to boil over into something angry – he’s pushing back against the faceless corporate entities who want to reduce everyone to nicely labelled cogs in their marketing machine. He’s not a respondent – he’s a real person! Dig carefully enough and you’ll find other nuggets of real feeling amongst all the fools’ gold: Things are piling up so fast is one, the price is much too high another, and I don’t know which to follow a third – all moments where I can hear traces of distress and confusion in the speaker’s voice. There’s a noticeable transition in line 24 and again in line 42 when the speaker uses the word we rather than I. This subtle shift from the personal to the public voice implies the respondent starts speaking for others as well (he even uses the word people in line 37) as if there’s a widespread groundswell of dissatisfaction with the modern world. Towards the end of the poem, he stridently declares: we are the consumers and the last law makers in the manner of an activist whipping up a crowd with a rallying cry or call to arms. In this line, he asserts himself defiantly and we are even given a touch of alliteration, last law makers, one of the poem’s only poetic embellishments, to accentuate this moment of genuine anger against the commodification of our lives.

Which makes his final recommendation even more surprising. Because, immediately after this moment of defiance, the speaker goes right back to toeing the company line again. After such a litany of complaints and existential worries, he ends up reporting: So finally, I’d buy it. I don’t know about you, but I felt a little let down by this sudden course-correction. This is intentional on Porter’s part. In the modern world, consumer creep is so insidious and corporate power so all-pervasive that any alternative proposition as to how we could live differently, or live better, flickers like a guttering candle, blazing briefly… then gone. Himself a beneficiary of a consumer society, the speaker has unwittingly internalised its values, even ones he despises. The sudden turn at the end (the moment a shift in tone, perspective, or the direction of the argument occurs in a poem is the turn) is a pessimistic reminder that recognising problems with modern society is not the same as dealing with them. Words are just words without meaningful action and our speaker doesn’t really want to bite the hand that’s feeding him.

His final little protest then – refusing to give the product a ‘best buy’ rating – is an act of mere tokenism. He resists in this one detail because he knows he can get away with it, revealing the illusion of power that consumers enjoy. It’s like when your parents tell you to turn off the music or the TV and, when you wait just that extra second longer to do what they ask, they don’t say anything. They let you get away with the little things because you’ve already obeyed with the big things, which is all that really matters. The poem’s speaker, the unwilling ‘respondent’ who responded anyway, already received and used his Life product, just as the vast majority of people eagerly and unquestioningly participate in and consume whatever society has to offer. The evidence is in the way he phrased his protest: instead of trying to smash the system, or refusing to fill out the report, he selfishly grabbed the tiny bit of power offered him to nudge himself a little higher in the system’s hierarchy: If its experts are called philosophers or market researchers or historians, we shouldn’t care. We are the consumers. Through a kind of metaphorical renaming, the speaker labelled himself a consumer. No one forced him to say that, but he did it anyway – implying that he’s already a slave to market forces. In a clever loop composition, we are reminded of one of the poem’s opening lines in which, on rereading, the compliance of the speaker seems ominously automatic, robotic in quite a sinister way: I have completed the form you sent me… No one forced him to, but he did it anyway…

At the end of the day, Porter fatalistically asks, what is the alternative? What choice do any of us really have?

Suggested poems for comparison:

- On the One Hand by Peter Porter

Porter wasn’t only an experimental poet. As his friend and former student Sean O’Brien once wrote: ‘the vast body of his work contains poems of many kinds.’ In this short example, Porter shows off his skills with meter and rhyme as well.

- The Woman Who Shopped by Carol Ann Duffy

Duffy’s poem also criticises the insidious creep of consumerism into all corners of society as a woman, who only goes out to buy an apple, can’t stop shopping until that’s literally all she does. Caution: explicit language.

- In the Department Store by T.S. Eliot

Consumer-culture rose in Western societies after World War Two, but it wasn’t invented then. Written around 1920, but not published until 1996, this poem describes a lady who works in a shop – and is gradually internalising the lifeless porcelain qualities of the dolls she sells.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying A Consumer’s Report at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring the extended metaphor in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Peter Porter’s poem? Were you also surprised when the speaker recommended buying the product of life? What do you think the ‘competitive product’ might be? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

good

Thank you so much for this.I was looking for an analysis to help with my IGCSE exams and this is perfect!