Arthur Yap is woken from his daily snooze by a piano lesson gone awry

“Yap… captures the pompous ambition of academia with its gaze more on status than clarity of thought”

Andrew Howdle, writing for Singapore Unbound

You may have heard of the ‘helicopter-parenting’ technique. Coined in 1969 by psychologist and educator Dr Haim Ginott, this term has since become part of our popular lexicon, referring to a parent who is involved in a child’s life in an overprotective, overbearing or dominant way, that is in excess of ‘normal’ parenting. Dr. Ginott took the phrase from teenagers he was interviewing, who described how their parents would always hover around supervising them. In 2011, Yale professor Amy Chua popularized a related term, ‘tiger-mom’, in her book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. Often ascribed to Asian parents (although anybody can adopt this style), tiger-parenting prepares children for the future by emphasising education and skills. Tiger-moms can seem very tough and disciplinarian when viewed from other cultural points of view. In an afternoon nap, Arthur Yap reveals what overly strict and disciplinarian parenting looks like when taken to an extreme. Written from the point of view of a neighbour who is trying to enjoy an afternoon snooze, he is interrupted by the sounds of his across-the-street-neighbours, a mother and son engaged in a shouting match over the unfortunate boy’s bad grades. The mother in the poem stretches the limits of acceptable parenting, using fear, threats, and physical violence because her son struggles to measure up to her high expectations of academic success:

the ambitious mother across the road

is at it again. proclaiming her goodness

she beats the boy. shouting out his wrongs, with raps

she begins with his mediocre report grades.

she strikes chords for the afternoon piano lesson,

her voice stridently imitates 2nd. lang. tuition,

all the while circling the cowering boy

in a manner apt for the most strenuous p.e. ploy.

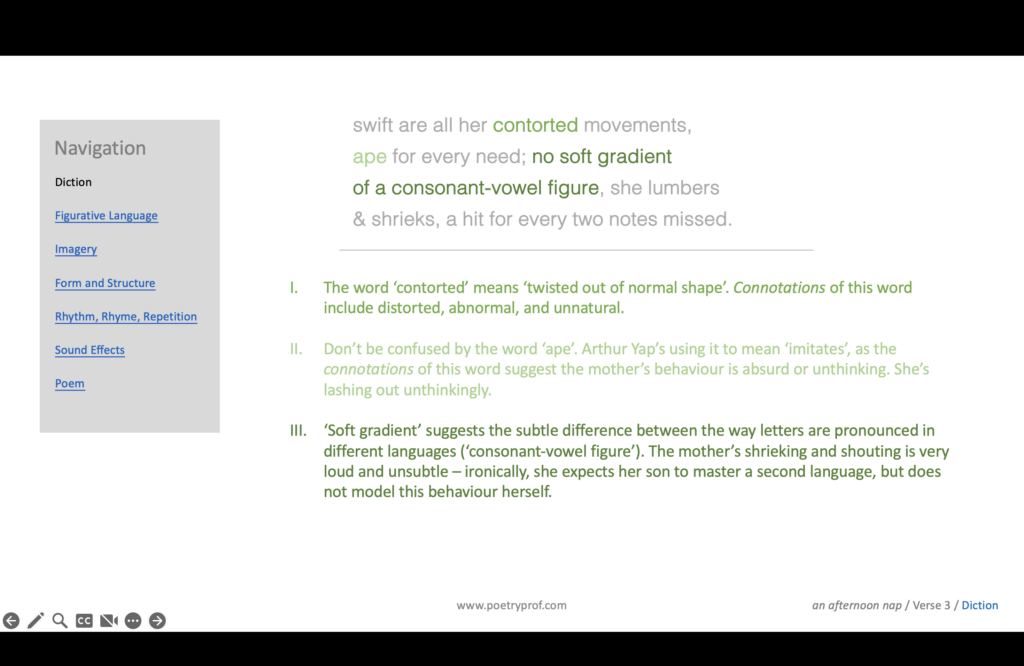

swift are all her contorted movements,

ape for every need; no soft gradient

of a consonant-vowel figure, she lumbers

& shrieks, a hit for every two notes missed.

his tears are dear. each monday,

wednesday, friday, miss low & madam lim

appear and take away $90 from the kitty

leaving him an adagio, clause analysis, little

pocket money.

the embittered boy across the road

is at it again. proclaiming his bewilderment

he yells at her. shouting out her wrongs, with tears

he begins her expensive taste for education.

Arthur Yap is a Singaporean poet and, if you were to ask young men and women from Singapore whether they recognise the scene presented in an afternoon nap, they would almost certainly say that they recognise some aspects from their own upbringing. At the very least they would have friends or know people in their class at school who went through a similar experience. While the phrase ‘tiger-mum’ has become something of a stereotype, and certainly not all Asian parents would dream of using physical violence in the manner of Yap’s mother across the road, the common Singaporean culture of parenting nevertheless seems stricter and more authoritarian to outsiders. Children do not enjoy as many freedoms and are rigidly scheduled to attend extra lessons outside of class. Parents have high expectations of children’s academic success in terms of grades. While any national system is of course complex and multifaceted, as a generalisation Singaporean education places emphasis on tests and test scores, and children are expected to get perfect scores by ambitious parents, who are afraid of being embarrassed by comparison with other overperforming kids within their social circles. The word ambitious features in the first line of the poem, and goes a long way towards explaining why the mother in the poem puts her son through such a punishing schedule of extra lessons, home tutoring, and activities designed not only to improve his cultural capital (the afternoon piano lesson that features here, for example), but also turn him into a walking, talking status-symbol proclaiming the virtues of her flawless parenting for all to see and admire. Alongside ‘ambitious’, proclaiming is the most important word in understanding the mother’s psychology: it’s not enough that her son excels, she needs everyone to hear about it and understand that he’s a success because of how good a parent she is. Her dominant personality is further implied through a structure called anaphora, which is the repetition of words and phrases at the beginning of lines of poetry. Throughout the first and second stanzas, the pattern she + verb is repeated in this manner (she begins… she beats… she strikes…), making her an active force while the poor boy sits frozen like a rabbit in the headlights, a passive victim of her hostility.

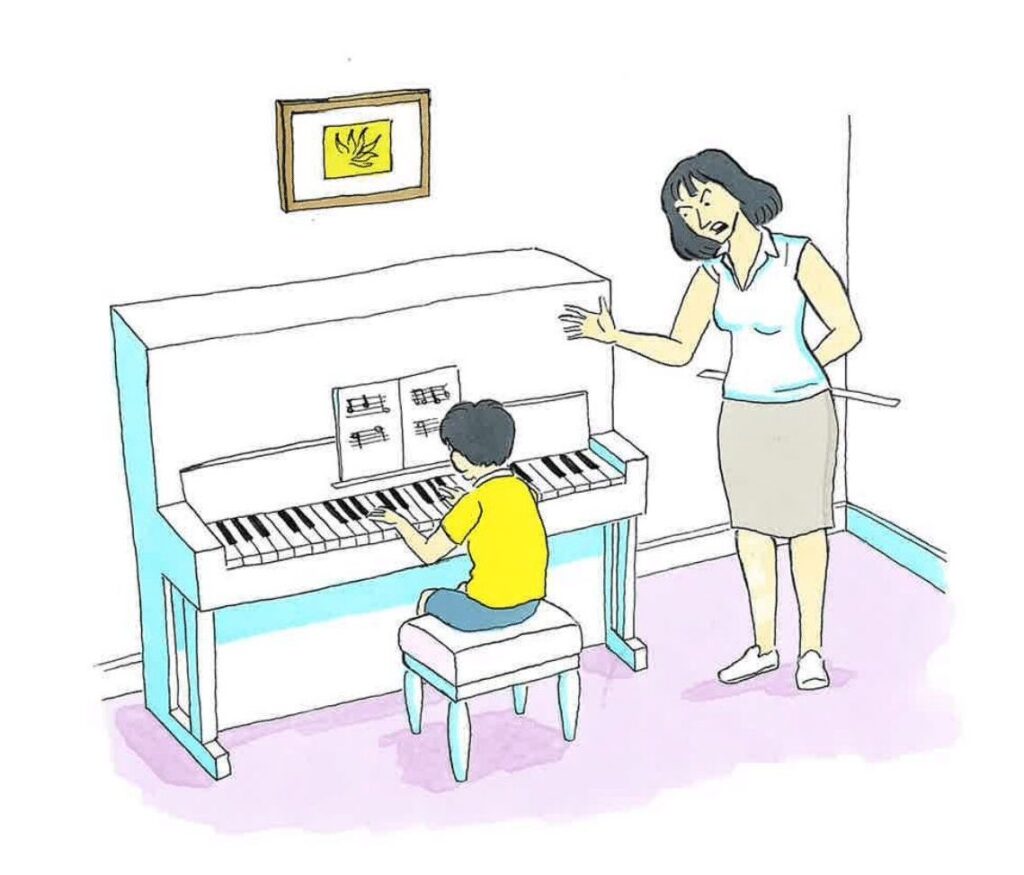

However, even by strict Singaporean standards, this mother takes things waaaay too far. Amy Chua adopted the term tiger-mum simply because she was born in the Chinese year of the tiger – but Yap’s mother metaphorically displays the attributes of this fearsome animal. She circles her cowering boy like a predator stalking her prey, and she’s swift and merciless when she strikes. Yap describes her contorted movements, as if she’s more animal than human, twisted up with rage at her son’s poor performance in his lessons. Verse two is especially menacing, featuring a sinister sibilant sound as she circles threateningly; you can hear sibilance in words and phrases such as she strikes, voice stridently, circling and strenuous. The phrase she lumbers & shrieks helps readers visualise a large, dominant animal rearing up on hind legs, screaming through bared teeth. Yap actually uses the word ape in the phrase ape for every need; while here it means ‘apt’ or ‘according to’, as in the mother’s actions are apt for the need of striking her son, the word can’t help but call attention to the mother’s animalistic qualities as she prowls menacingly around the living room, ready to pounce on every little mistake. Half-rhymes or weak-rhymes such as road/raps/grades, lesson/tuition, monday/money, kitty/little convey an uncomfortable tension, as if things are far-from-okay in the speaker’s neighbour’s house. Yap frequently enjambs one line of poetry into another (enjambment is the technique of letting one line of poetry run into the next without end-stop punctuation marks breaking the flow. Examples are plentiful: every line in stanza one enjambs into the next), accentuating the sinister, predatory effect of the imagery as the mother circles and stalks her tormented ‘prey’. The non-capitalisation of words at the beginning of each line is deliberate too, which not only emphasises the effects of enjambment, but calls attention to the idea that, if Yap – a successful and published writer – does not follow totally accurate writing conventions, why should the boy be expected to master advanced clause analysis, something beyond expectation for his age? It’s a subtle way of Yap reminding us that writing (and learning) can be playful and fun, something entirely lacking from this experience. On the contrary, the boy’s mother only looks at grade scores and report cards. We don’t find out exactly what has made her react in this way, and Yap’s non-conventional style adds another layer of unpredictability: like the unfortunate boy in the poem, we are never quite sure when and how mother is going to lash out next.

Whether or not the mother’s behaviour crosses a line into abusive territory is a matter of interpretation, but Yap couches the whole poem in a violent diction of verbal and physical assault that strongly implies his criticism of this way of parenting. He draws from an abusive lexical field of words such as beats, shouting, raps (meaning to hit with the knuckles) strikes, shrieks, hit, yells and shouting again. Many phrases such as she beats the boy and the repeated is at it again are composed of monosyllabic words that, when read aloud, impact the ear in a flurry of short, sharp strikes. On several occasions, Yap uses punctuation to further accentuate the physical impact of his writing, embedding full stops into lines of poetry to create a staccato effect. Both 2nd. lang. tuition. and p.e. ploy abbreviate words using full stops, adding a tactile dimension to both the mother’s abrupt shouts and the physical punishment she metes out. Thanks to plosive alliteration (made with the letter P), the words p.e. ploy strike the ear just like the mother’s palm falls on her son’s bare skin, giving us an auditory expression of the pain he endures. In fact, throughout the whole poem, Yap intensifies violent language using hard consonant sounds (alliteration and consonance) as frequently as he can. Plosives (made with the letters B and P), dentals (D and T) and gutturals (G, C and K) create an audio assault that mirrors the mother’s physical actions: beats the boy, begins with his mediocre report grades, strikes chords, circling… cowering, p.e. ploy, tears are dear, take from the kitty… jab at a random line and you’ll probably hit one of these hard sound patterns. The combination of different hard consonants creates cacophony, a dissonant and uncomfortable mixture of sounds that don’t easily harmonise. Combined with Yap’s unpredictable use of rhyme (we already mentioned half-rhymes; at other times we hear full-rhymes like boy/ploy and the occasional internal rhyme too, such as his tears are dear/appear) the sound effects in the poem can be jarring, unpredictable, and occasionally overwhelming – all accusations that can be levelled at the mother herself. One line describes her as no soft figure of a consonant-vowel gradient, referring to one of the advanced concepts the boy is expected to master. Her manner is anything but soft and, rather than moving through a smooth gradient of behaviour, she switches suddenly into modes of anger and abuse, something conveyed exceptionally well through the poem’s cacophonous sound patterns. On top of all this, the auditory violence of the poem finds direct expression through onomatopoeia: words like hits, shrieks, raps contain the sound of the action they describe, letting us directly experience the whirlwind of action as the mother flails away at her poor, put-upon progeny. Let’s not forget, the whole poem begins with the idea that she’s so loud the speaker is startled out of his pleasant afternoon nap all the way across the road!

Like any good villain, the mother doesn’t work alone and her henchmen (or, in this case, henchwomen) make an appearance in stanza four, in which Yap implies the transactional quality of all this education her son is receiving (he uses the word dear to mean ‘expensive’). Extra-curricular classes are often thought of as ‘enriching’, yet there’s a subtle pointing to the idea that, because it costs so much money, enrichment is only for the rich. The boy’s tutors, miss low & madam lim, hint at a wider society in which a lucrative industry takes advantage of middle-class and wealthy-class parents’ obsession for surrounding children with structures and schedules. While their names sound pleasingly musical (presumably one of them is a piano teacher and those Ms and Ls harmonise perfectly), the repetition of such similar-sounding names implies a certain soullessness and impersonality to the teachers, as if they are identikit copies of one another. They pop up seemingly out of nowhere and their first action, to take away $90, is almost ironic – aren’t teachers supposed to give, not take? From their brief appear-disappear moment in the poem, the impression formed of the teachers is a little venal, as if they’re only in it for the money. Addressed as miss and madam, they seem overly formal and brusque. That’s not to say they don’t do their jobs properly and Yap points out what the boy learns: an adagio, clause analysis. Yet the list-like structure of this line suggests education as a conveyor belt; as soon as they are done with this class, the lims and lows are onto the next, collecting as many fees as they can rather than building any kind of nurturing or mentoring relationship. As well as nudging us to ponder how age-appropriate such lessons might be, and whether his life is truly enriched compared to, say, going outside to play with his friends, the final words of this stanza (little pocket money) suggest that the wider cost of all this expensive education is borne by the boy himself. It’s not about money, necessarily, but intangibles such as pressure, opportunities lost, a life spent in scheduled study, a living room or bedroom becoming a de-facto classroom from which there’s no escape. Through an afternoon nap, Yap asks us to ponder the further (emotional, social, psychological) costs of shutting the boy up in his room to work on his sentences and scales all day.

The final stanza gives us an idea of where all this is heading, as the embittered boy finally snaps, his pent-up anger and frustrating recoiling onto his helicopter mother. This kind of shift or reversal is very common in traditional poetry, especially in the last stanza, and Yap doesn’t disappoint. As the boy shouts back at his mother, Yap pointedly repeats the word proclaiming from the first lines, but now applies it to the boy who, in his bewilderment, doesn’t fully understand why his mother berates and beats him so harshly. Yet, through the word embittered implying that he’s been shaped by his mother’s treatment of him, we see how he’s unconsciously adopted his mother’s behaviour and attitude. The transfer of that violent lexical field (yells, shouts) from her to him delivers a warning that overbearing and aggressive parents are creating a cycle of misery: while he may make mistakes in his grammar tests, he’s internalised the mother’s lessons all too well and mirrors her posturing, demeaning language, and aggressive behaviour. Above all, this idea comes from the mirrored structures of the first and final verses, both beginning with the parallel phrases: the ambitious mother across the road is at it again… the embittered boy across the road is at it again…a choice that strongly implies the cyclical nature of this unfortunate family’s interactions. Yap’s clever reversal prompts us to think beyond the last line. What kind of person is this boy growing up to be? Will he treat others in the way he’s been treated? If such parenting is culturally embedded (the line expensive taste for education suggests that the mother is following a widespread ‘fashion’) how hard will it be for people to change?

While such questions are raised and not directly answered, the framing of the poem helps us understand the wider debate around parenting styles in Singapore. The speaker is a distant observer, awoken from an afternoon nap by the noisy row emanating from his neighbour’s house. While probably annoyed that his cozy snoose has been so rudely disturbed, otherwise, he should be pretty neutral on the issue of education. Yet, from his objective point of view, he nevertheless paints the mother as a vicious person, quick to lash out verbally and physically when her son disappoints her. From his position, she lacks kindness, empathy, and acts selfishly. Her insistence on constant improvement and perfect performance isn’t for the benefit of her son, but for the benefit of herself in terms of how others perceive her; her son’s successes and failures reflect her, so when he ‘fails’, she’s failed, which is something she cannot accept. It’s clear that her style of education isn’t producing the desired results (that word bewildered, placed near the end, connotes confusion rather than clarity), yet she doesn’t acknowledge her own role in this sad state of affairs. Rather, she pushes all the blame onto a child who may be trying his best – with unintended but all-too-predictable consequences.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- location by Arthur Yap

By some standards, Yap is not a prolific poet, publishing only four collections in his lifetime. This poem is from his first collection, only lines, published in 1971. You’ll recognise some of Yap’s distinctive stylistic flourishes, such as the way he doesn’t capitalise headwords and his careful, precise employment of punctuation to create deliberate stops.

- Little Boy Crying by Mervyn Morris

In this poem, Morris explores how to discipline a child by switching points of view from a father who smacks his child, to the effect of the smack on the child’s himself.

- Thanking My Mother for Piano Lessons by Diane Wakoski

And here’s another side of the story. In this beautiful, musical poem, Wakoski looks back on a childhood rich with learning and practice, interweaving the struggle for mastery with memories of the relief that piano playing brought, and still brings, thanks to her mother’s sacrifices.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying an afternoon nap at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining alliteration, consonance, and cacophony.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Arthur Yap’s poem? Do you recognise the educational culture he’s describing? What do you think will happen as the boy gets older? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Hi,

This website has helped me prepare so much for my upcoming IGCSE exams. I am understanding the poems in depth and it has been very refreshing. Is there any chance you will be posting an analysis for ‘The Road’ and ‘The Capital’ which are also a part of this set?

Hi Ashley,

Thank you for your message, I’m so glad you are enjoying the website. It’s lovely to receive such encouraging feedback from readers. Good news – I just posted The Road blog today, so you can find this on the site. Hopefully, I’ll be able to post The Capital soon as well… watch this space!