Mervyn Morris debates whether it could ever be right to smack a child.

“… his poetry… has ranked him among the top West Indian poets.”

Ralph Thompson (Poet)

Think back to your early childhood and you might remember (perhaps with a touch of embarrassment) something like the scene from today’s poem. It doesn’t matter whether it was a quick smack from your mum or dad, a stumble and a harmless fall, or a skinning of the knees in the school playground. It’s the type of pain that doesn’t cause any lasting damage – but the shock and surprise made the young you burst into floods of tears, likely accompanied by howls out of all proportion with the little bit of pain you actually suffered! Jamaican writer Mervyn Morris’ poem Little Boy Crying does a great job of bringing this scene alive:

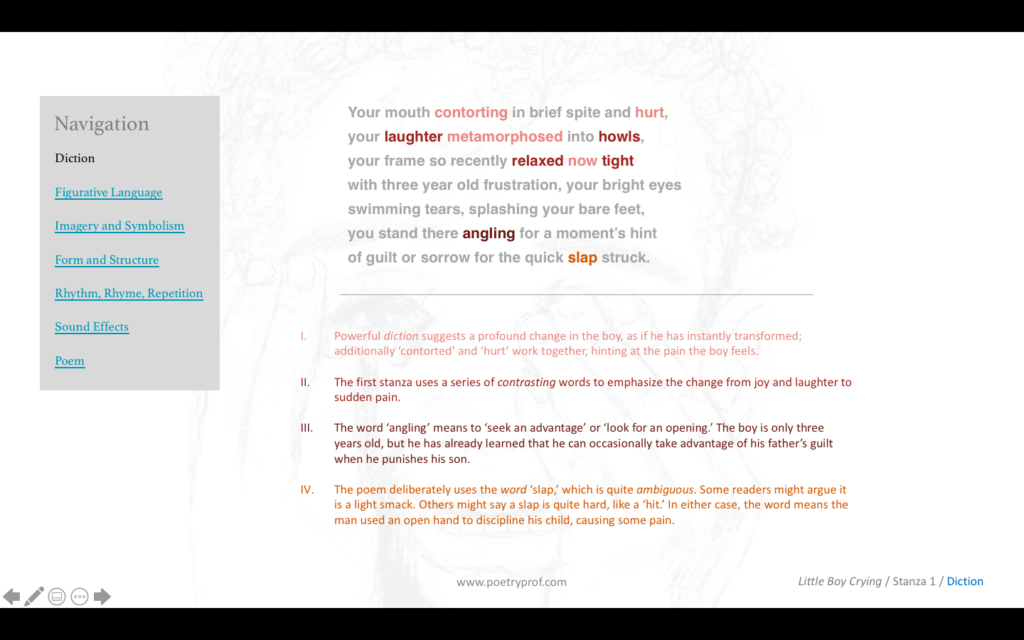

Your mouth contorting in brief spite and hurt,

your laughter metamorphosed into howls,

your frame so recently relaxed now tight

with three year old frustration, your bright eyes

swimming tears, splashing your bare feet,

you stand there angling for a moment’s hint

of guilt or sorrow for the quick slap struck.

The ogre towers above you, that grim giant,

empty of feeling, a colossal cruel,

soon victim of the tale’s conclusion, dead

at last. You hate him, you imagine

chopping clean the tree he’s scrambling down

or plotting deeper pits to trap him in.

You cannot understand, not yet,

the hurt your easy tears can scald him with,

nor guess the wavering hidden behind that mask.

This fierce man longs to lift you, curb your sadness

with piggy-back or bull fight, anything,

but dare not ruin the lessons you should learn.

You must not make a plaything of the rain.

Taken from his collection I been there, sort of (published in 2006) Mervyn Morris’ perfectly crafted poem contains within three short stanzas the story of an entire father-son relationship; the tears, love and misunderstandings that arise when the father, for reasons not obvious in the poem, disciplines his child by smacking him. That small action ripples outwards and has unintended consequences for both father and son: the young boy begins to hate his father for doling out what he sees as unfair punishment; the father is hurt in ways more profound than the quick pain caused by the smack. From his point of view, he’s doing what he perceives is necessary, the lesser of two evils perhaps, to keep his young charge safe from harm. The tragedy is that neither of them can see what the other is truly feeling: the brilliant – and quite unusual – way that the poem switches perspective in the middle of three stanzas lets us see the unintended consequences of the smack. Unfortunately, the young child doesn’t realise that his father’s actions came from a place of love… until it’s far too late.

Opening with a description of the boy’s mouth contorting in brief spite and hurt, the first stanza describes the moments immediately after the boy begins to cry and creates a set of before/after contrasts. We see laughter set against howls, relaxed frame juxtaposed with tight and bright eyes suddenly unleash floods of tears. The way the little boy’s howls of pain are out of all proportion to the harm actually suffered is expressed through exaggerated images showing the boy swimming in tears. In the second line the word metamorphosed doubles down on the idea of contorting; the words are quite extreme (deliberate exaggeration for effect is called hyperbole), as if the boy has suffered a great harm. But – compare contorting to brief… hurt. The first suggests quite an extreme twisting of the lips, as if the boy has suffered great pain. The second reassures us that the hurt was brief and no doubt soon faded.

Quite cleverly, we don’t find out what happened to produce such a spectacular flood of tears until the end of the first stanza. It was a smack, administered by his father, that caused all this trouble. Described as a quick slap struck, the final words of the stanza can be used to argue either that the smack was small and harmless or that the boy is entitled to emit such howls of pain. The word struck clashes with quick in the way of an oxymoron – quick seeming to suggest ‘painless’ and struck ‘painful.’ The word slap sits in the middle: some might say an open-handed blow is much less than a hit; others that it amounts to the same thing. On one hand the words quick reassures us it was more a gesture of violence than violent itself. On the other hand, the sounds of these words are hard: gutturals and plosives (made with Q, CK and P; quick slap struck) are hard and sharp, and the pattern of three monosyllabic words in quick succession acts like musical staccato, accenting the beats and giving them an edge that mimics the pain of a smack. Rhythm works together with sound to produce this effect. You may have noticed that the poem is loosely iambic, which you can see in these lines with accents marked:

you stānd/ there āng/ ling for/ a mō/ ment’s hīnt/

of guīlt/ or sōr/ row for/ the quīck/ slāp strūck./

Occasionally, though, Morris throws in a measure of two stressed syllables, known as a spondee. As you can see in the last phrase the spondee means three words in a row (the quīck/ slāp strūck/) are stressed when the poem is read aloud. Combine rhythmic stress with alliteration, and the weight of the slap hits your ears like a sharp blow.

Actually, the contribution of sound should not be underestimated throughout the first stanza. Especially assonance. The little boy’s howls of frustration are summoned through assonant sounds, including O (contorting, metamorphosed into howls, so, old, sorrow) and long I/EE sounds: tight, bright, three year, eyes, tears, feet. Mix in some aspirant H (hurt, howls, hint) sounds at the end of three different lines, and you can almost hear that breathy, panting wail that young children are wont to let out after the shock of pain. Look closely at the sounds at the end of each line: almost every one is a short accented consonant, normally T: it’s as if the echo of that short sharp smack reverberates through the whole stanza, mixing with the young child’s cries.

Whether the smack really hurt or not, the poem shows us the potential deviousness of young children and suggests that not all three-year-olds are as innocent as they may seem. This boy has learnt at a tender age that he can leverage his own pain for some kind of revenge. You might call this ‘emotional blackmail’ and it’s amazing to see the little boy practice this on his father in the first stanza. Suddenly, we wonder if the howls of three year old frustration were completely genuine: the word angling reminds us of fishing, the way an angler will use a lure to sucker an unwary victim. In fact, one of the meanings of the word ‘angle’ is ‘to position oneself for an advantage’, and the little boy is already smart enough to know that he might be able to dupe his father into feeling guilt or sorrow for what he’s done. The word spite is also another clue, meaning ‘a desire to deliberately hurt another.’ These words complicate the picture of a sweet and innocent little boy and make him seem quite underhand. We already discussed that the poem hasn’t yet given a reason for the slap, but a careful reader might be able to make inferences from language which very subtly implies the boy was acting in a careless or thoughtless way: relaxed and laughter imply he may not have been paying attention to those around him and could have been in, or causing, danger. The poem contains enough references to water (swimming, splashing, tears, rain) to build a case that water might be involved. In that case, one might argue, the father may have been correct in his action if it was to protect and correct, rather than punish, his son.

The second stanza switches perspective, and we are suddenly plunged into the make-believe fairy tale world of a child, where all is black and white and there is none of the complexity or moral grey areas we were just discussing. Submerged in the simple psychology of a three-year-old, we get to see the unintended consequences of the slap. Using this stanza, we can involve Morris’ poem in the wider debate over corporal punishment and whether violence begets violence. There seems to be an admission on the part of the poet that violent actions – even small and excusable ones such as this smack – engender violent thoughts which, given time, may translate into violent actions themselves. The poem doesn’t dwell on this idea too much, but the possibility lingers under the surface, particularly given the adoption of a violent and hate-filled diction: apart from the obvious you hate him in the fourth line, chopping, kill, trap, cruel, victim, plotting and dead are all words from the second stanza that connect to violence, killing and revenge.

The second stanza is testament to the skill with which Morris immerses us in the perspective of a small child so completely. I love the allusion to Jack and the Beanstalk (chopping clean the tree he’s scrambling down) which casts the boy as the hero in a fairy story. Even more so the metaphors which summon up how small and helpless the boy feels when his father exercises physical control over him: the ogre towers above you, that grim giant and colossal cruel are all metaphors that convey the idea that power wielded by adults against children comes from size above and beyond anything else. And it’s important to note that these are all true metaphors and understand the distinction between a metaphor and a simile. Where a simile says that one thing is ‘like’ another, a metaphor says that one thing ‘is’ another: in the boy’s eyes the father isn’t just ‘like’ an ogre, he’s actually ‘become’ an ogre, transformed (metamorphosed) into something evil. He’s not ‘like’ something cruel – he is cruel, the personification of nastiness, his cruelty reinforced by hard guttural C and G alliteration (colossal cruel, ogre, grim giant). And, if you want more grist for the violence-begets-violence mill, cast your eyes to the end of the stanza two; see how plotting deeper pits to trap him in takes those hard sounds (plosive P and dental D / T this time) and blends them into the boy’s imaginary violent actions.

The third stanza reverses the perspective once more, and we’re back behind the father’s eyes. Just as the picture of an innocent boy was complicated by deviousness, now the picture of a fierce man is undermined. On the outside he may look ogre-ish, but Morris shows us the smack hurts the father on the inside much more than it hurts the child. Another metaphor – hidden behind a mask – and the word wavering are the key moments in the third verse. And the images of his father playing piggy-back and bull fight are made poignant by the fact that they only exist in the father’s imagination. Alliteration does some of the emotional work again: look how the words longs to lift you are given weight and feeling by the combination of alliteration and that loose iambic beat: This fiērce/ mān lōngs/ to līft/ you, cūrb/ your sād/ (ness). Make sure you contrast the diction in this stanza with that of the last: lift, curb, longs and learn replace chopping, trap and so on. Where the boy experiences the slap as a painful punishment, the father sees it as a lesson you should learn.

The poem ends with a final line like a musical coda: You must not make a plaything of the rain. Some commentators read the final line as literal: the father smacked the boy because he was outside playing in the rain. But I’m not convinced by this. It doesn’t seem to fit with the third-stanza image of a father who loves his child so fiercely that he would smack him for such a reason. To my mind, the punishment doesn’t fit the crime. Instead, I like to read the final line metaphorically. It contains the sound of aphorism, an old and wise truth. Assonance gives it this quality, the long A sounds in make, play and rain, as well as it being a single line presented by itself (the technical name for this is monostich). The little modal verb (must) conveys strength of feeling: this is the life lesson that the speaker wants to impart. The line invokes rain as a metaphor for the boy’s tears and the word plaything implies that, all along, the father was aware of the boy’s deviousness (connect it with angling and spite). In that case, the final line seems directed squarely at the boy, whose manoeuvring caused his father more pain than the quick smack ever could. But the meaning of the final line also fits with the idea of a father who, longing to soothe his child’s hurt is desperate to pick him up and cuddle him, anything to stop those heart-rending cries – but in doing so make a plaything of the lesson he was compelled to teach. See how the final line echoes the last line of the poem proper: dare not ruin the lessons you should learn.

Yet, as well as having that universal quality, the line also feels intensely personal. Morris’ father died in 1948 when Morris was 11 years old, which opens up the possibility that the poem is a kind of elegy, an acknowledgement that he has learned the (sometimes hard) lessons his father tried to teach him. Much too young to understand his father’s actions at the time (you cannot understand, not yet), now Morris is older and wiser and can see through the eyes of father and son each one.

Suggested Poems for Comparison

- The Day My Father Died by Mervyn Morris

Written about the death of his father and told through the eyes of an 11-year-old boy, midway through this poem swerves into a tribute to his mother. The way Morris steps back for her grief and resilience to take centre-stage is heart-warming and heart-breaking in equal measure.

- Those Winter Sundays by Robert Hayden

A true companion piece to Morris’ poem, Hayden tells of a stoic man’s small acts of love. Each morning he would rise in the freezing cold to stoke the fire for his indifferent son. It wasn’t till after his father’s passing that the speaker understood the true warmth of his father’s small acts of kindness.

- Mother To Son by Langston Hughes

This poem sits alongside Little Boy Crying in the category of ‘tough love’ poems. There’s no smacking here, but an honest and straightforward account of how hard life can be, and a reminder that you can’t sit down even for a moment if you want to climb those stairs.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Little Boy Crying at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the way Morris employs Metaphors.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What do you think of Little Boy Crying? On which side of the smacking debate do you fall? What’s your take on the final line of the poem? If you have your own take on Morris’ poem, why not share your ideas in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

An extremely sensitively written analysis. Brings the perspective of the child and the father in sharp focus and shows how the actions and reactions are juxtaposed against each other. Brought the poem vividly to life. Thanks

Hi Atiya,

Thank you for your kind words. I really enjoy the way this poem gets inside both the father’s and the little boy’s heads – the more I read the last Line, the more I think the speaker is treating his own son just the way his father treated him.

This was really a unique way of analysing the poem. Really helping me as I prepare for IGSCEs

The analysis had a wider and more accurate scope than many I had read in the past and than even my own understanding. I feel more empowered now to discuss it with my group and feel slightly conflicted in regards to the last line (as one should feel when interpreting a work that only the writer can truly explain). Thank you and keep up the good work.

In the poem, the little boy crying, the poet highlights the misunderstanding and differences between the two characters, the father and the son, in several ways.

Firstly, In the first stanza, the author describes the reaction, and emotions of the child from being slapped. At this point, we are opposed to the father, as the appeal to our emotions( pathos) swings us into this feeling. The author describes the boys “recently relaxed body” going taught, and the “laughter” that he was only just enjoying quickly turns to “howls”. Then, his eyes start to “swim” with tears, as he looks up at his father hoping to see his grief for what his father just did. In this first paragraph we are immediately on the child’s side, frowning down upon the father, a misunderstanding which is revealed to us later on in the poem.

Secondly, in the second stanza, we feel the rage of the boy, describing the father as an “ogre”, and how he wants to “trap him” in a pit or cut down a tree he is “scrambling down”. This reaction seems a little extreme, feeding doubt into our immediate thought to support the child. Adding to this, the author describes the child looking up, seeing none of the grief he was looking for, as the author mentioned in the first stanza, and instead he sees his emotionless monster of a father, yet again we are fed doubt, the child is looking for a reaction, anything to get him out of this, and yet again it is an enraged opinion of what just happened, it was he who was just slapped, and he is also a young child, with out of control emotions, yet again planting another seed of doubt.

Thirdly, In the final stanza’s, the author gives us the father’s perspective, revealing to us his true intentions. This is revealed as the author writes ” the hurt your easy tears can scald him with” by this he means that the tears burn the father, he hates it, but he doesn’t dare respond because he believes it necessary to teach the child a lesson. He is teaching him a lesson out of love, as a father, who knows what is right, compared to a young three year old, with out of control emotions, which is ironic, because the kid hates it, as we can see because he describes the father as an ogre . The kid was in the wrong all along, all this hate he felt, and the hate we felt was just a misunderstanding, the child’s emotions are out of control, and we were too in a way. Then, in the final stanza the author reveals to us that the child was making a “plaything of the rain”.

In conclusion, in the poem, the little boy crying, the poet highlights the misunderstanding through the poem. The journey starts from the perspective of the child, his emotions out of control, looking for grief in his fathers eyes, to the second, hating his father, describing him as an “ogre”, to the third, realising that the father was teaching him a lesson out of love, to realising that the child was the one in the wrong, playing in the rain. The poet takes us on this journey, deliberately revealing information slowly over the poem, to create this effect, and change our opinion, and realise our misunderstanding.

The way we, the readers are revealed more and more information over the course of the poem, until we are finally given the full picture, with the father teaching the child the valuable lesson of doing what he is told. Our eyes are clouded from the start of the poem, immediately we defend the crying child, with out of control emotions. This journey was truly helpful to learn, and i shall cherish this poem for years to come.

\