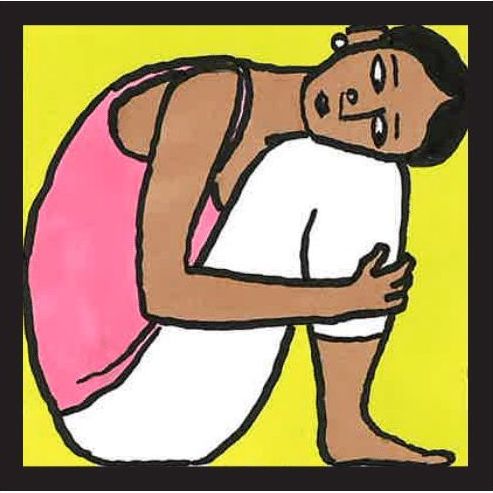

Life’s a squeeze in Sampurna Chattarji’s depiction of Mumbai.

“In a flash, a city comes alive…”

Arundhathi Subramaniam

When I was young, I had the smallest bedroom in our house. I think it was less than half the size of my brother’s room. I didn’t mind because I liked sleeping in a cabin bed, with a ladder to climb and desk built-in underneath. But, compared to the subject of today’s poem, I was lucky. I could leave my small bedroom and go to the living room, kitchen, one of two bathrooms – and we had a huge garden to play in. The woman described in today’s poem has to squeeze everything she has into one tiny room; one of thousands – hundreds of thousands – in a city that feels like it’s bursting at the seams. If you have any experience of Asian cities like Hong Kong, Tokyo, or Mumbai, you’ll know something of the incredible human density of these places, with more than 70,000 people crammed into each square kilometer. Having lived in Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai, Sampurna Chattarji is well-placed to reveal the reality of life for millions of people, not just in India, but across Asia and increasingly the rest of the world too. As rents soar, landlords partition houses and flats into ever smaller units, so families live back-to-back, one on top of each other. Developers cut costs and hike profits by building higher towers with smaller and smaller rooms, heedless of the psychic and emotional toll of having to force life into such tiny and inappropriate spaces:

Her balcony bears an orchid smuggled in a duffle bag from Singapore. It’s roots cling to air. For two hours every morning the harsh October sun turns tender at its leaves. Nine steps from door to balcony and already she is a giant insect fretting in a jar. On one side of her one-room home, a stove, where she cooks dal in an iron pan. The smell of food is good. Through the window bars the sing-song of voices high then low in steady arcs. With his back to the wall, a husband, and a giant stack of quilts, threatening to fall. Sleeping room only, a note on the door should have read, readying you for cramp. Fall in and kick off your shoes. right-angled to this corridor with a bed, trains make tracks to unfamiliar sounding places. Unhidden by her curtains, two giant black pigs lie dead, or sleeping, on a dump. Every day the city grows taller, trampling underfoot students wives lovers babies. The boxes grow smaller. The sea becomes a distant memory of lashing wave and neon, siren to seven islands, once. The sky strides inland on giant stilts, unstoppable, shutting out the light.

Chattarji’s poem is particularly concerned with space – or rather, the lack of space for the poem’s subject to live in. Referred to only as she and her, we never learn her name or who she is; she could be any one of millions of people squeezed into tiny, rented niches that are totally unsuitable for one person – let alone two – to live in. Amusingly, the woman’s husband is barely in the poem. Mentioned only once at the end of the second verse, he features as just another item in a long list she accommodates in her limited space; propped up against the wall, he resembles a piece of furniture stowed out of the way. We discover that her one-room home is only nine steps from door to balcony; into this narrow area, she crams living space, bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen – not to mention all of life’s paraphernalia such as cooking pots, clothes and shoes, foodstuffs, toiletries, and so on and so forth. Reflecting the preoccupation with space that the woman must feel, every now and again the poem includes numbers: two hours, nine steps, two pigs, seven islands – although most important is the number one, repeated in the first line of the second verse, one is the number of rooms she can call her own. And even this space is rented, so is not really hers, and may have been misrepresented. Wanting to disguise an unpleasant reality, her agent or landlord neglected to mention just how little space her money can buy her: Sleeping room only, a note should have read reminds us that her situation is temporary and perhaps untenable. Having worked in advertising for seven years, Chattarji would have had first-hand knowledge of agents’ shady obfuscations, and this line reads a little ruefully.

The word home has connotations of safety, security, solidity, and permanence. I don’t get any of those feelings from this poem; instead, from the title onwards, people are put into Boxes, a metaphor that reduces ‘homes’ into tiny cubes that can be packed away, picked up, and moved on at a moment’s notice. Boxes are utilitarian and convenient – but who wants to live in a box? A home should be somewhere one can relax at the end of a busy day; a personal haven in which one can rest and recover. Again, this simply isn’t the reality in this poem, which implies an almost complete lack of privacy in such a densely packed city. In stanza three, we discover her room is adjacent to a rubbish dump and the word unhidden reveals how hard it is to keep the outside world out. Seeking to recreate her subject’s lived experience, Chattarji crafts a dense melange of sensory images that is stimulating to read but might be quite exhausting to endure every day. As well as visual imagery (more on this later), tactile (impressions of clammy heat activate your sense of touch), kinesthetic (images that recreate movement) and even olfactory (smell) images blend together in a potent concoction all squeezed into a tiny space. The sheer variety overwhelms: there’s a hot stove and an iron pan, heavy and burdensome, not to mention a fire risk placed next to a stack of quilts (contrastingly soft, but threatening to fall over).

Some of these experiences, taken in isolation, would be pleasant: my taste buds came alive at the mention of dal, a delicious curry made of lentils, and Chattarji confirms that the smell of food is good. Too, neighbour’s voices drifting through her window are described using the pleasant onomatopoeia sing-song. But what should be neighbourly and comforting sounds become oppressive when one is forced to hear them twenty-four/seven. Described as moving high and low in steady arcs, the sounds are everywhere, intruding on her personal space, pressing her down and hemming her in. Sibilance plays a part here, a concentration of S sounds in the phrase sing-song voices… in steady arcs give the voices a sharp, cutting edge. Most people would probably agree that apartments backing onto railway lines might get a little too loud: the clacking of MRT (Mumbai Rapid Transit) trains trundling past at all hours of the day and night is evoked through dental alliteration (especially the letter T) mixed with gutturals (G, hard C and K): kick off your shoes, trains make tracks, corridor, curtains, two giant black pigs lie dead are all examples from verse three alone. Clashing different hard consonant sounds together (there’s even some plosive P and B here) creates a discordant and aurally unpleasant effect called cacophony, a word that means ‘a harsh mixture of sounds’ and recreates the sonic experience of the girl who lives this day in, day out.

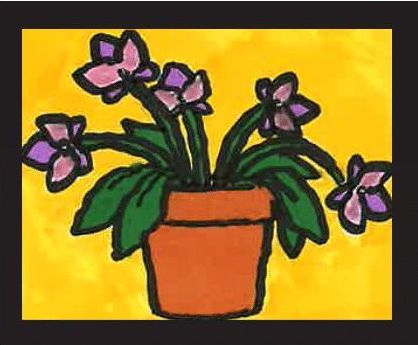

In an attempt to liven up her space, the woman has placed a pot plant on her tiny balcony – which struggles to bear the load of just a single orchid. Conflating this with the woman’s own struggles, the sounds of the first line (alliterating B in balcony bears; guttural consonance in balcony, orchid, smuggled and bag) suggest the general hardship of life lived in such a constricted space. Through the use of pathetic fallacy, a technique by which human emotions are transferred onto aspects of the natural world, the orchid can also be understood as a symbolic stand-in for the woman herself. Her desperate, improvised quality of life is mirrored in the way it’s roots cling to air; the word cling personifies the orchid and implies the suffocating feel of living in a space that’s totally unsuitable for life. This feeling is intensified through the description smuggled in a duffle bag. Not only is the idea of being stuffed into a bag stifling, the breathy-sounding F in the word duffle mimics the stuffy rasp of someone gasping for breath in a hot, constricted space.

The density of Mumbai’s urban squeeze is reflected in Chattarji’s creative use of space, otherwise known as spatial form. Her poem is presented in four almost perfectly even stanzas; hold the poem at a distance and each verse resembles a tiny room stacked on top of one another. Move your eyes closer, and the lines seem organised to use every available inch of space on the page, much like her subject must find ways to cram all of life’s necessities into her one-room flat. Chattarji’s sentences almost never match up with the length of the lines: she uses enjambment to start and end sentences on different lines. Once in each verse she writes a short sentence that seems to be squeezed in and in a memorable list in verse four she packs students wives lovers babies together, eliding any punctuation marks as if there’s simply no more room in the line. She eschews rhythm and does not give her poem a rhyme scheme – these organised elements would undermine the slightly chaotic feel she’s trying to transmit. Chattarji wants her poem to look cluttered and feel improvised, an act of sympathy with people who must somehow fit everything into spaces that simply aren’t big enough.

Equally creative is Chattarji’s use of sound effects, particularly near-rhyme, internal rhyme, assonance and consonance that creates sonic links between words in the same verse. She presses words up against one another, squeezing even more into increasingly tiny spaces. Let’s look at stanza one more closely to see (or hear) the aural density of her poetry. Firstly, the ‘or’ sound in the word orchid is picked up in Singapore, echoed twice in for every morning and once more for good measure in the word door. A similar ‘ar’ sound echoes in the words air/harsh/jar/. Smuggle/duffle are near-rhymes (this effect is created when the vowel sound or the consonant sound rhymes, but not both) as are sun/turns and insect/fretting. The same effects reoccur in the second stanza: on/one/iron/pan/song, food/good, room/home, through/window/low, back/stack and wall/fall mix up rhyme, alliteration, assonance, and auditory imagery, blurring the boundary between various techniques. So many different-yet-complimentary ideas – Mumbai’s muggy climate, density of urban construction, the squeeze of so many people living on top of one another, the woman’s claustrophobic one-room home – are expressed through density of sound in the poem. Why not see if you can identify some of the same effects replicated in stanza three for yourself?

Therefore, the more we read the more her one-room apartment feels like a prison rather than a home. In verse two the detail of security bars over her window transforms the room into a cage cooping her up inside. The visual imagery of the poem draws a network of straight lines: train tracks, the right-angled arrangement of bed and corridor, a stack of quilts, low steady arcs, window bars all create square shapes with the woman trapped on the inside. A feeling of profound claustrophobia makes it seem like she’s desperate to break free. Early on we are given the metaphor of her being an insect trapped in an overturned jar, struggling to get out. Chattarji uses the word fretting, which connotes the juggling of day-to-day worries, but also sounds like the useless tap-tap-tapping of an insect trying vainly to escape (listen how consonance lets you hear this action through the repetition of the letter T in giant insect fretting). Trains make tracks to unfamiliar sounding places is a wistful line in which her longing to get out is mixed with our realisation that she’s never experienced anything other than her immediate surroundings; she doesn’t recognise the names of different places. Later, the claustrophobic pressure ramps up as the size of her room shrinks further: as the city grows taller, contradictorily, the boxes grow smaller. The final line of the poem is couched in the language of entrapment, shutting out the light, an image that implies her space has become so confined that not even a glimmer of daylight can get into her impossibly small cell.

The final image typifies the way Chattarji positions the city in complete opposition to the natural world. Even a simple pot plant has to be smuggled in, a choice of word (diction) suggesting that natural things are illegal and have to be kept hidden or are viewed with suspicion. The construction of apartment blocks in dense clusters means she only sees the sun for a measly two hours every morning before it passes behind neighbouring buildings. Admittedly, this might be something of a blessing, as in a tropical climate the sun can be unbearably hot even in October; here it is described as harsh. Noticeably though, on touching the forbidden orchid’s leaves the sun turns tender, implying that the unbearable heat of the city is not a completely natural condition. Dense construction, insulating building materials, and millions of people all burning energy in a confined space mean that cities can feel stiflingly hot. Fear and pain peppers the poem’s diction: harsh, threatening, cramp, kick, trampling, lashing. Through her window, the woman can see two giant black pigs who have somehow come to live on the nearby rubbish dump. Unmoving, they might be sleeping – or they might be dead, another word that implies there is no way for the natural and human worlds to co-exist.

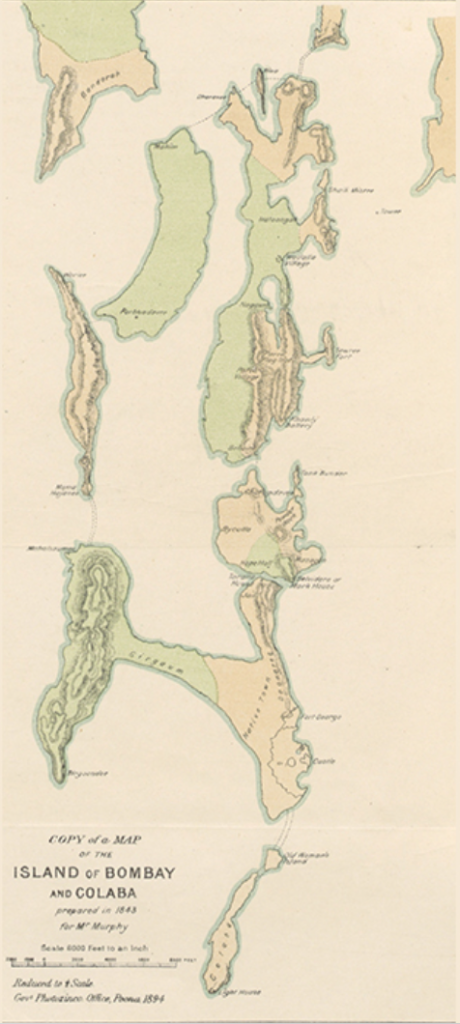

Nowhere is the squeezing out of the natural world more poignant than in the final stanza. The mention of seven islands in a sub-clause, as if this is a forgotten or unimportant detail, is a significant allusion to the story of Mumbai’s origins that’s well worth reading. The seeds of the present were sown in the past, and the artificial joining of the seven islands was the first step towards the building of a megacity that seems so inimical to living things. Begun by the Dutch East India Company and the British in 1668 and taking almost 200 years to complete, channels between the seven islands that form the bedrock and foundation of Mumbai were closed, seawater drained, and earthworks and fortifications built-up. It must have been an incredible feat of engineering – but it didn’t come without cost. Today, symbols of nature (such as the sea and sirens, mythical creatures who used to call to fishermen and sailors; their songs were seductive, beautiful, deadly) have vanished, replaced by artificial neon advertising displays that cast the final verse in an unnatural, electronic glow. Chattarji recalls nature’s futile fightback, remembering how, in distant memory, the sea and sky threw themselves impotently at the man-made walls of the ever-expanding city. Putting sibilance to good use again (siren to seven cities, once) this sound recreates the gusting wind, lashing waves and driving spray and simultaneously releases her anger that we’ve lost our connection to the natural world, forgotten about the past, and can’t imagine alternative ways of living anymore.

At the very end of the poem, Chattarji crafts an apocalyptic image of anti-nature wrought by ceaseless urban expansion. The entire visible world is metaphorically transformed into building blocks (or boxes) pressing against one another as skyscrapers (giant stilts) crowd the horizon so completely that natural light is extinguished under a canopy of concrete and steel. At the end of the poem, sibilance becomes the defining sonic motif of urban development; sinister, relentless, unstoppable.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Packing by Sampurna Chattarji

This poem’s title echoes Boxes – but it’s very different. Brief, enigmatic, beautiful, the poem imagines putting a butterfly and a snake together into a box.

- Glasgow by Alexander Smith

The good, the bad, the beautiful, and the ugly are all laid out in Alexander Smith’s brilliant rhyming poem about the city where he worked in a cotton factory for twelve years and eventually settled with his wife and family.

- Rooms by Charlotte Mew

In this tragic poem by a turn-of the century English poet, Mew remembers her life playing out in a series of ever smaller and bleaker rooms. Symbolising all of life’s disappointments, Mew explores how a home that should be a sanctuary can become a prison cell under the wrong circumstances.

- Cities by Hilda Doolittle

Doolittle imagines a city of ‘dark cells’, teeming with people crowded into few tiny streets, everything cast in black shadows. A powerful poem from the Imagist movement.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Boxes at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2.50 and includes:

- Study questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A continuation exercise to help you practise analytical writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how sensory imagery is used in the poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Sampurna Chattarji’s poem? How does the poem make you feel about the living conditions it describes? What is your interpretation of the final image? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.

Absolutely amazing work! I was able to clearly understand the hardships faced by the narrator and how Chattarji conveyed a clear message to us. Keep it up!

Thank you so much for your comment – I very much enjoyed working on Boxes, I think it’s one of my favourites from this selection. I’m happy to have helped unlock the poem a little bit for you.