What should be her sanctuary becomes Charlotte Mew’s prison cell.

“Far and away the best living woman poet, who will be read when others are forgotten.”

Thomas Hardy

If you’re anything like me, you might enjoy shutting yourself away in your room, away from the prying eyes of parents and siblings, and see your own room as your sacred personal space. Perhaps you feel comfortable there, or more able to express your true self. But for the writer of today’s poem, Rooms are more like cages than sanctuaries. In Charlotte Mew’s experience, the rooms in which she spends her life symbolically cut her off from the wider world, stifle her freedom to express herself, and are sites of personal tragedy.

I remember rooms that have had their part In the steady slowing down of the heart. The room in Paris, the room at Geneva, The little damp room with the seaweed smell, And that ceaseless maddening sound of the tide – Rooms where for good or for ill – things died. But there is the room where we (two) lie dead, Though every morning we seem to wake and might just as well seem to sleep again As we shall somewhere in the other quieter, dustier bed Out there in the sun – in the rain.

Once you’ve read the poem through, spend a couple of moments considering the title: Rooms is a polysemic word, it has more than one assigned meaning. As well as the conventional meaning of a room in a house, the word also suggests the idea of ‘space,’ ‘living-room,’ or ‘breathing-room’ in which one can stretch out, explore the limits of one’s potential, or simply relax and recharge. ‘Room to breathe’ or ‘room to grow’ are common enough expressions that convey these meanings. You should be able to locate this tension in Mew’s poem; she was forced to live under the weight of social convention, as well as difficult personal circumstances, which placed severe limits on her confidence and affected her outlook on life. As the rooms of the poem grow smaller and diminish, her yearning to unfold, to stretch out, and to free herself of such limitations grew stronger.

Mew uses the simple idea of living in rooms as a metaphor that expresses the feeling that her life was always very small. Written in the 1920s, only a few short years before her death, Rooms begins with the poet looking back over her life (I remember rooms…) and expressing feelings of frustration and disappointment at the way things turned out for her and her family. This slow, emotional death is expressed neatly in the second line as the steady slowing down of the heart. Born into a family of seven children (Mew was the eldest), three of her brothers and sisters died and two more were committed to insane asylums, leaving only herself and her sickly sister Anne. Her mother was famously domineering, even going so far as to forbid Charlotte to speak in an Isle of Wight accent. In 1898, her father passed away, leaving Charlotte and her sister in financial trouble and forcing them to downsize by renting out half their family home to make ends meet. Later, their home would be condemned, forcing Charlotte and Anne to share a rented room (possibly the little, damp room described so pitifully in the poem). At the end of her life, Charlotte entered a nursing home – so, on one level, the series of ever smaller and more disappointing rooms of the poem stand in for the increasingly difficult and narrow circumstances of her life.

As rooms played their part in the slowing of her heart, alliteration and consonance play a part in creating the stifling feeling of living within tightly proscribed limits – and Mew’s yearning for freedom from those limits. I’m sure you noticed the alliterative R sounds of line one and sibilant S sounds in line two. Indeed, these sounds are important in creating that note of regret and frustration in her tone of voice. But I’m interested to show you some less obvious uses of sound in the opening two lines as well. Using the letters M and N, nasal sounds are made by trapping air in the nose and closed mouth – therefore nasal is very good at suggesting ideas such as confinement or supressed emotion. Nasal is particularly strong in the first words of the poem and is noticeable in the second line too: remember rooms, in and down all contain nasal sounds. Another type of alliteration is aspirant, made with the letter H. Good at expressing a release of pent-up emotion, you can find aspirant alliteration in the first lines as well: have, had and heart. Taken together, these two opposing sounds encapsulate the dramatic tension in the poem; Mew lived under stifling personal and social restrictions from which she yearned to be released.

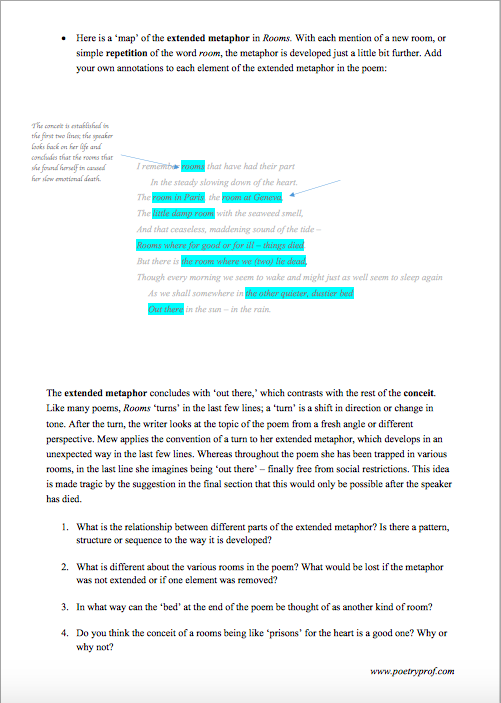

An extended metaphor is a type of metaphor that extends across a whole text. Also known as a conceit, you can see how carefully Mew establishes the conceit in the first couplet by marking it with a full-stop. Reading carefully to punctuation should help you see how the metaphor is extended. In lines three to six, before the next full-stop, she develops the conceit by letting us peek into some of these tragic rooms, as if taking us on a dispiriting tour through her life’s failures and embarrassments. One damaging episode is alluded to in line three: the room in Paris (an allusion is a mention of something outside of a text that normally remains unexplained). Mew’s previous writing had been included in a magazine called Yellow Book and Mew knew Ella D’Arcy, the one-time assistant editor of this publication. According to her biographer, Penelope Fitzgerald, Mew was deeply attracted to D’Arcy and, in 1902, travelled to Paris to meet her. The visit was a bitter disappointment and the room in Paris is most likely the actual hotel room on Rue Chateaubriand in which Mew was rejected. Ten years later she suffered another humiliation. Having fallen in love with the novelist Mary Sinclair, she plucked up the courage to make her advances and was again rebuffed. Mew never again attempted to initiate a romantic affair. The room in Paris and the room in Geneva must figure strongly in her memory as the sites of these emotional disasters, and so are associated with the lessening of life’s possibilities in the poem. However, it’s also important to note that these experiences are NOT elaborated upon at all. In fact, none of the poem’s many rooms have any warm moments or memories described within them; they flash by like a list of bare, empty spaces. The overriding impression of the rooms in the poem – and the life lived within them – is of bareness and emptiness, as if that life was barely lived at all.

This feeling of a diminishing, ‘lessening’ life becomes more tangible in the next couple of lines. The third room we are taken to is described as the little damp room with the seaweed smell. The word little suggests that, although the world is wide (Paris, Geneva, tide), Mew’s experience of the world is becoming increasingly narrow. It’s likely that the little damp room by the sea is inspired by the rooms that Charlotte and her sister were forced to take after their family home was condemned. You might think that living so close to the sea would be a pleasant experience, but the imagery of this room is sparse and unpleasant. It’s damp (think mouldy and cold) and a seaweed smell pervades the air. In case you’ve never got up-close and personal with seaweed strewn along the beach, let me tell you this isn’t your sushi-grade seaweed. Piled rotting on the sand, seaweed can have a salty, redolent, funky smell that can be quite rank – not a smell that you’d enjoy being surrounded by day and night. Besides this, lines four and five describe the smells and sounds of the ocean (and sound is amplified by sibilance in seaweed smells) – but not the sights – as if Mew is denied one of the essential pleasures of living by the sea. She uses the word maddening to express what it is like to be constantly next to the ceaseless pounding of the waves. Think about the infamous use of dripping water as a torture technique and you’ll understand what she’s getting at in this line. There’s an interesting opposition between the movement of waves that come in and out and the petrified, frozen life that the speaker feels she is trapped in. If you’re interested in exploring the connection between the human world (represented by rooms) and the natural world of tides and seaweed, you might like to consider how, when social restrictions begin to darken her outlook on life, the ocean becomes an antagonist as well. There’s also an autobiographical element to the use of the word maddening – after the death of her sister, Mew became delusional and increasingly fearful of suffering the same fate as her brother and sister who, you’ll remember, had been forced into mental institutions.

The end of the second section is marked by one of those words which tends to leap off the page and grab our attention: died. This diction (choice of word) is almost always emotive – and its appearance here causes us to pause for a moment and ask, what things died? Love is one obvious answer, given the anecdotes we’ve already recounted. But we know the poem is striving for more than a simple recount of Mew’s personal disasters. Things expresses universal ambitions that young people might feel – things like optimism, hope for the future, happiness and the confidence to express one’s identity are all reasonable suggestions at this point in the poem. There’s a note of resignation in her tone of voice when Mews admits that for good or for ill – things died, and the hyphen functions to both emphasise the last words of the line and create a sense of inevitability, as if the writer accepts that this is perhaps the future that fate had in store for her. Knowing that both Charlotte and her sister made a conscious decision not to enter into romantic relationships that might produce children because they feared passing on negative family traits might help you understand this note of resignation in the face of despair.

The repetition of the words died / dead forces us to examine this more closely. There’s a subtle shift in tense that points to the distinction between the figurative ideas we just discussed, and something more literal. Prefaced with the word (two) in brackets, it’s almost certain that the second use of the word dead refers to her sister Anne who sadly developed cancer. Mew would care for Anne until she died in 1927, leaving Charlotte bereft and alone. And, to add another layer of meaning to our consideration of dead, Mew wants us to consider that – even before Anne died – their reduced circumstances led her to feel like they were enduring a kind of living death. She expresses this in the extended line: Though every morning we seem to wake and might just as well seem to sleep again. The use of the word seem – twice – is a masterful touch. Technically, this word marks a simile, so by repeating it Mew gives us the impression that she is no longer sure of the distinctions between the living world, the dead world, or the world of sleep. So dreary has her life become that one state is equivalent to the other. Liquid alliteration made with W and L (we, wake, well), assonance (every, seem, seem, sleep) and sibilance (seem, just as well, seem to sleep) contribute to this impression by blending the sounds of the words woozily one into another, as if Mew struggles to see through half-open eyes, drowsy now with lethargy, half given-up on life already.

As we’re looking at the long, extended line, now might be a good time to consider the wider aspects of form in Rooms. Written in one stanza of ten lines (called a dizain; a traditional French form) the single block of text resembles one of those small, square rooms that imprisoned Mew throughout her life. You can no doubt see certain lines are offset (lines two, nine and ten) and the eighth line is stretched as if ‘breaking out’ of the box shape. In this way the poem’s spatial form represents the thoughts and feelings of the poem, as if the lines themselves are reluctant to be confined to such a limited space. When the eighth line ‘breaks out’ of its cage, this should be a joyous moment – but the content and sounds of the line are relentlessly glum, conveying a sense of hopelessness. You can trace this idea through the poem’s rhythm too. Written in a steady, regular tetrameter (meaning there are four stressed beats in each line), in the last three lines the rhythm falters, stutters and breaks down, expressing the need to be free from restriction – or suggesting the faltering and weakened mental state of the writer who finds herself always ‘reduced’ in one way or another.

The use of spatial form also calls our attention to the last two lines. Quite often a poem will change in tone, shift in direction, or develop in a new and unexpected way towards the end. Called the turn or volta, this feature is a formal component of sonnets; but Mew performs a turn at the end of Rooms also, when she finally breaks free of the social confinements that circumscribed her life and escapes into the wider world – in one sense at least:

As we shall somewhere in the other quieter, dustier bed Out there in the sun – in the rain.

In terms of this unexpected change of direction, Out there is particularly striking. Throughout the whole poem we’ve gotten this palpable sense that the writer is invisibly confined – trapped by the tiny rooms of her life. Suddenly she seems to break free. But even the thin ray of sunshine at the end of the poem is negated by careful reading. With awful irony, Mew picks up the metaphorical idea of sleep being a kind of death and takes it to its logical conclusion by imagining her and her sister resting in a quieter, dustier bed. The clue is in the second adjective which suggests that beds actually means ‘graves’ – picture some kind of dusty sepulchre or cobwebbed tomb. Mew sadly looks forward (we shall…) to her grave (which is, of course, just another kind of room) as a release from suffering, because at least her grave will be out there in the sun – in the rain. These last words symbolize what has been missing from her life: warmth, comfort, love, perhaps, in the case of the sun – excitement, danger, exposure to risk in the case of the rain. It’s incredibly sad to think that Charlotte lived in such despair that the only time she could imagine experiencing these modest ambitions is after she has died.

For this is the dreadful truth about the rooms of Mew’s life. They are a prison that contained her inside the walls of social expectations and shut her away from the wonderful possibilities of the wider world. Rooms is simultaneously an intensely personal poem, crammed full of tiny autobiographical titbits, and at the same time a universal poem easily appreciated by anyone who chafes under frustrating rules and restrictions. As a Victorian poet, a woman, and (most probably) a lesbian, Mew lived in a most socially repressive culture. For a woman of her talents and proclivities, these social, personal and professional restrictions must have been suffocating. Reading the poem through, you can almost feel the ever-shrinking walls of the rooms that she was put in tightening like fingers around her throat, cutting off her air supply and slowly choking her to death.

This reading of the poem is not so far-fetched. In 1928, saddened by the death of her sister, who had been her lifelong companion, delusional and fearful of being committed to an asylum, Charlotte Mew took her own life.

Suggested poems for comparison

- The Farmer’s Wife by Charlotte Mew

Rooms were something of a motif in Mew’s writing. In this poem, a young girl is forced against her will to marry a farmer. She escapes in the night, but is chased down and locked in the house. Just like Rooms, this poem presents the girl’s attic room as a kind of prison – and the poem is made even more poignant by being told in the voice of the farmer who has no idea of the misery he’s causing his reluctant bride (interestingly, the farmer speaks in dialect – something Mew was forbidden to do by her strict mother).

- Miss Drake Proceeds to Supper by Sylvia Plath

Another poem that vividly explores the fear of one’s surroundings, poor Miss Drake lives in an institution. To get to the dining room she must navigate the long corridors of the hospital – and the obstacles of her own mind.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Rooms at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining extended metaphor and conceit.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you like this analysis of Charlotte Mew’s poem? Did the rooms feel as stifling and oppressive to you? How do you respond to the final lines? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

i would likeyou guys to post a few essay questions to help those who are writing literature/lit

Hi Kristy – you can find essay questions and even a full essay plan for you to use for every poem in the Study Bundles. Why not download the free sample and have a look? I hope it helps you.

This website is very useful. The content is read and really helpful. Having access to other analyses will be of immense assistance to myself, colleagues and learner. I look forward to learning more via the platform.

Hi Veronica,

Thank you for your kind words and taking the time to write. I’m so happy you find my website useful – I hope you can find anlyses of more poems that interest you here as well.