Armies of ignorance conquer all in Matthew Arnold’s dark and disturbing vision of the world.

“Pessimism moves in swiftly as a tide”

Carol Rumens

Matthew Arnold was, it would be no exaggeration to say, a Victorian literary colossus. His poetry comprises only a fraction of his writing; he was a prose author, essayist and prominent critic. He held strong views about society, progress and learning and was scathing about the effect of religion on society, one of many ideas he discusses in today’s poem. He studied and admired the Ancient Greeks who he believed had laid the foundations for critical thought – in an ever-changing world, where knowledge could be sacred one day and obsolete the next, he strove to ‘observe facts with a critical spirit’ and ‘judge by the rule of reason.’ Dover Beach is a kind of Victorian version of The Matrix, a film in which people live in a computer simulation of a world that isn’t real. Of course, Matthew Arnold wouldn’t know about computer simulations and he was writing in a time before Freud’s ideas led to the birth of modern psychiatry too. But, if you could invite Keanu Reeves, Sigmund Freud and Matthew Arnold to one of those imaginary dinner parties, I bet they would have a lot to say.

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Dover Beach presents a fluid, changing world in which old superstitions and knowledges are being superseded by new understandings – and wrestles with the dislocating feeling of living in an insecure world of incomplete and unexplained knowledges. In another poem, Arnold describes himself as ‘wandering between two worlds; one dead, the other powerless to be born.’ Dover Beach subtly communicates this feeling, that the world is a kind of shared delusion that he can’t quite participate in. Trying to put your finger on what precisely troubles the speaker so profoundly is difficult. Despite the calm, assured opening, it soon feels like the foundations of the earth are not solid, that things we take for granted – things that seem permanent, like those vast white cliffs of England across the bay – are in fact intangible and could disappear from under our feet at any moment.

An insight into Arnold’s thought processes can be gleaned from the copious letters he wrote to his friends, family, and contemporaries. In one letter to his mother, dated March 3rd, 1865, Arnold wrote about a ‘daemonic element’ (a term he borrowed from Goethe) that underlies and undermines real life. Using modern parlance, again, we might term this element ‘the unknown’ or ‘life’s mystery.’ In the same letter he wrote that his purpose as a poet was to ‘to keep pushing on one’s posts (meaning lampposts) into the darkness’ as if writing can shine a light onto the mysteries of the world and drive the ‘daemonic element’ out. In Dover Beach, Arnold recasts the ‘daemonic element’ simply and purely as ‘ignorance’ and the high white cliffs of Dover are a kind of symbolic bulwark against ignorant armies, who would undermine the flimsy foundations of society. The poem is epic in scope: we meet warriors who fight on the side of reason and certitude (Sophocles), cross oceans, evoke history, and watch as the walls of the fortress of reason collapse. By the end of the poem the world has become a darkling plain, swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, where ignorant armies clash by night. The image is nothing short of apocalyptic.

Let’s look at how some of these ideas emerge more fully over the course of the first stanza. The opening line doesn’t give us much hint of the torrents of despair about to be unleashed. To begin with the speaker’s tone is sure and certain: the sea is calm tonight. Expressed in that most clear and obvious of grammatical structures– subject plus verb – the whole line, and especially the word is, conveys certainty, security and trust. Look around and see the tide is full and the moon lies fair. At first glance, everything is exactly as it should be. Over there is the French coast separated from the cliffs of England by a semi-colon, (a deliberate break or pause in a line of poetry is called a caesura) just as the Channel separates these two countries in the real world. Words such as full, stand, vast and the repetition of the verb is (meaning ‘to be’ or ‘to exist’, in the phrase how sweet is the night air) suggest the solidity and firmness of reality and the speaker’s confidence in his own mind. Repeated use of caesura, those many tiny breaks in the lines, though, imply the beginning of the speaker’s agitation, as if he’s casting his head this way, then that, sensing something is wrong and seeking reassurance in the permanent features of the world.

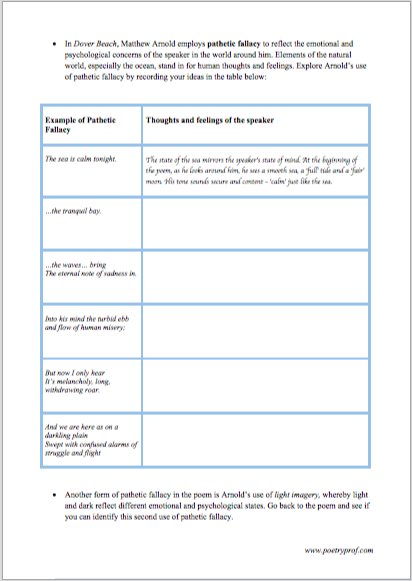

The key to unlocking Dover Beach’s secrets is pathetic fallacy; a literary technique, common in prose and poetry, whereby aspects of the natural world reflect human concerns. The most obvious uses of pathetic fallacy can be seen in romantic movies when lovers argue in the rain and kiss against the backdrop of a setting sun. In Dover Beach, light imagery is a form of pathetic fallacy, by which the shift from psychological certainty (the poem gives us the word certitude) to despair is mirrored by the shift from light to dark in the world around the speaker. At the beginning it’s all fair, gleams, glistening, bright – by the end of the poem all light has been extinguished and replaced by nor light, darkling plain, and night. The depiction of the sea is a second example of pathetic fallacy: the conflict between the land and sea, shown when the ocean flings pebbles against the high strand, can be understood as the assault on reason by the forces of ignorance, or the erosion of certitude that undermines the speaker’s confidence in himself and the world around him.

Actually the ocean is an incredibly ambiguous aspect of Arnold’s poem. Like in real life it’s ever-present (words like tide, waves, spray, sea, Aegean, and bay can be found in every stanza) but its symbolism is never fixed. To begin with the sea is calm and the bay is tranquil; but once doubt starts to creep into the speaker’s mind, the ocean becomes more agitated, so you might think it mirrors his state of mind. At one point the sea connects the speaker to the past (Sophocles long ago heard it on the Ægean) and at another it abandons the speaker to face an uncertain world alone: But now I only hear its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar. The sea’s shifting personality symbolises the poem’s central truth: nothing in the world is permanent or fixed. Writing in free verse allows Arnold to shorten and lengthen his lines as he likes, and at several points in the poem the staggered shape of the lines forms the image of the waves’ ebb and flow washing in-and-out on the page.

The opening stanza, then, gradually chips away at the supposedly firm foundations of reality and reveals that, actually, the world is a fragile construct indeed. Things seem permanent – surely those huge white cliffs will always be there? But time and tides will eventually erode them away to dust. Elements of nature are not unchanging. Tides go in and out, the moon waxes and wanes. The word lies is polysemic – it has more than one given meaning. Arnold uses it to show the moon in the sky, but we all know another denotation (given meaning) of the word lies is ‘to tell untruths’, ‘to trick’ or ‘falsify’. In other words – don’t believe what you see. Sure enough the solidity of the scene begins to waver: the light shining over the sea from France gleams and is gone, and the English cliffs, so vast and impenetrable are actually glimmering, twinkling incorporeally. The land appears moon-blanched which means pale, sickened and washed out in colour – as if it’s fading before our very eyes. Hard G alliteration (called guttural and heard in glimmering, gleams, and gone) mix with nasal M and N, which are much less solid, suggesting the thematic clash of permanence and impermanence.

There’s a significant turning point after the word Only, as the speaker moves from looking to listening, and starts to hear truths that his eyes couldn’t perceive. Sounds come in and out of focus; sometimes auditory images are loud, like the grating roar of the waves, at other times faint like the breath of the night wind. By the end of the first stanza any feeling of solidity and certainty has gone, replaced by a tremulous cadence (tremulous means ‘quivering’ or ‘shaking’). Now the speaker’s mind appears open to receiving a new truth about the world: that the security of permanent things – even cliffs and nations and the knowledge of one’s own mind – is illusory. At the moment of accepting this truth, he simultaneously hears an eternal note of sadness, as if living in a world of lies was preferable to having the truth laid bare. I promise this will be the last time I mention The Matrix, but if you watched that movie and thought he should’ve taken the blue pill, you’ll understand how the speaker feels.

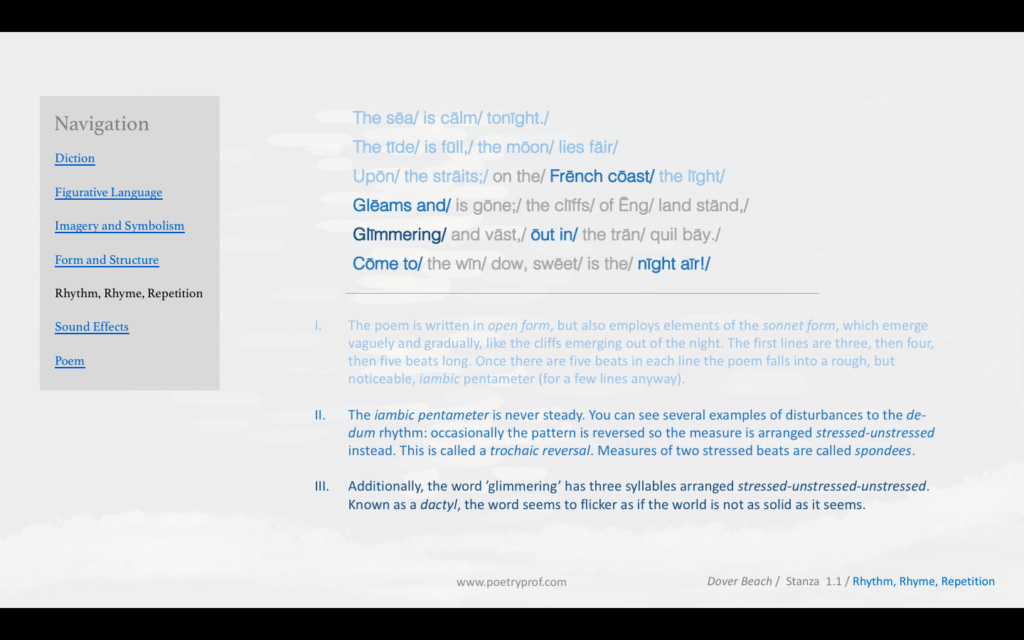

Speaking of turning points, you may have noticed that the first stanza of the poem is fourteen lines long (and especially-eagle-eyed readers will have seen the second two added up are also fourteen lines long) – which is the length of a traditional sonnet. But it doesn’t look or sound anything like a true sonnet. The rhyme scheme is fiendishly complicated, for a start, and the meter is all over the place. It might be best to describe the first stanza of the poem (and the next two put together) as a ‘free verse sonnet,’ if such a thing is possible. Arnold was an incredibly modern person and poet and, even in his use of poetic form, he blurs the lines between tradition and modernity. He adopts an open form, where he is free to alter the meter, line length, rhyme scheme and other elements of form at will. Let’s look at the first three lines with accents marked:

The sēa/ is cālm/ tonīght./

The tīde/ is fūll,/ the mōon/ lies fāir/

Upōn/ the strāits;/ on the/ Frēnch cōast/ the līght/

You can see that the first line is three iambic feet long (each one of these unstressed-stressed combinations is called a foot); the second is four feet long; it’s not until the third that the traditional five foot line of iambic pentameter becomes apparent. Even then, the rhythm of the third line is not comfortable (and the French coast is not properly iambic) and in other lines of ten syllables there are rarely five steady iambic measures (read gleams and is gone… out loud and you’ll hear the stress fall on the first rather than the second syllable). Arnold keeps the form of his poem vague and insubstantial, like those cliffs glimmering obscurely in the dark. His vision of a world that’s neither there nor not-there is perfectly replicated by the lack of clarity in the poem’s form. For fun, take what you know about the traditional sonnet form (for instance, end-stopping, rhyme scheme, structure, turn or volta) and see if you can spot Arnold using, abusing, or discarding it altogether.

In Dover Beach, then, people are caught up in an existential dilemma. The stories we tell ourselves about the world (and the poem is particularly interested in one of these stories – religious faith) may be untruths; but they are comforting and shield us from despair and alienation (the symbolism of the cliffs as a bulwark or shield comes in to play again and again). Without these ‘comforting lies’ people are left like exposed shingles, naked in the dark. Arnold presses the sea into service once more when faith is metaphorically described as the sea: the Sea of Faith was once, too, at the full and around earth’s shore lay. At one time, he says, Faith surrounded the whole world, its strength resonating through the powerful assonance of the line (sea, faith, earth, lay and once, too, full, around and shore). But Arnold only evokes this image as another example of how permanent things – this time the centuries-old institutions of faith – eventually fail.

The dilemma of religion (Arnold’s relationship with faith is not as simple as it might first appear; although he was critical of religious hypocrisy, his father was a Catholic minister) is captured in the language he uses to describe the way the Sea of Faith… lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled. On one hand you might say the fricative sounds of the line (Faith, full, earth, folds, furled) are soft, pleasant and soothing. The word bright, associated with light imagery, pits faith against the chaos later wrought by the armies of ignorance. But on the other hand, you might detect a more sinister note in those sounds, as if religious faith is hypnotic and deceiving. After all, the sea is frequently associated with human misery through a lexical field of words like turbid, melancholy, and sadness. Both possibilities come together in the simile of the word girdle, a belt that cinches around the waist. The brilliance of this metaphor is that a girdle can be either supportive or uncomfortably constricting. He personally had no time for religion – but seemed to recognise the truth that without comforting stories, people have no interpretive framework for understanding the complexity of the universe and inevitably fall into despair. He even describes a world without faith as drear, meaning ‘sorrowful’ and melancholy.

It might seem difficult for us to appreciate that these were very real concerns for Matthew Arnold and many of his contemporaries in the Victorian age. Arnold saw himself as working towards the ‘intellectual deliverance’ of Europe and his grand ambitions can be seen in his allusion to Ancient Greece (Sophocles long ago heard it on the Aegean) by which Arnold aligns himself with forces of reason and critical thinking. An insight into the exciting possibilities of living in an age of dizzying breakthroughs in fields as diverse as astronomy, history, science, philosophy and so on can be gleaned from this list from the final stanza of Dover Beach: for the world, which seems to lie before us like a land of dreams, so various, so beautiful, so new… You’ve no doubt already spotted the word seems which prefixes the list and tells us none of these things are true. If you didn’t, don’t worry, as Arnold immediately and repeatedly negates all these wonderful possibilities anyway: Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain. He must have looked about him at the squalor of ordinary people’s lives, incessant warfare on the continent, ravages of sickness and disease, and seen merely the broken dreams of the industrial revolution.

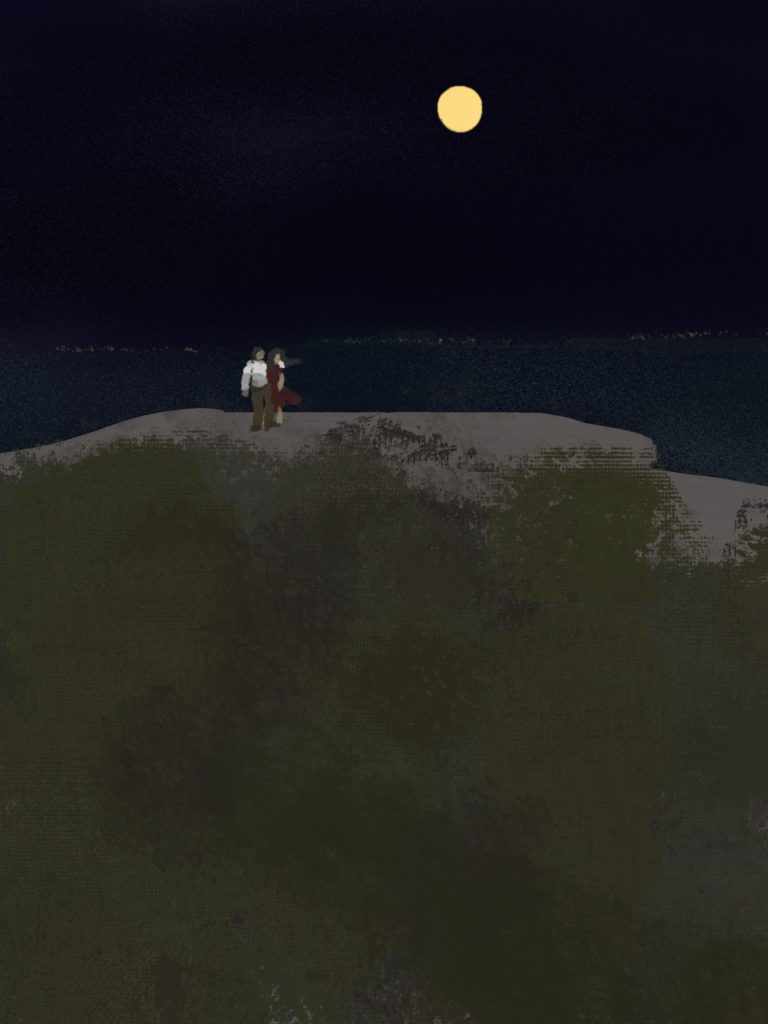

In such a bleak world where does one seek solace? If one can’t believe in the permanence of nations, one’s own sense of reality, the deceptions of religion, the promises of a utopia for all to enjoy – or even the certainty that the land will always rebuff the sea! – where can one turn? The speaker in Dover Beach finds the answer in love and companionship. As early as the sixth line the poem began to address an unseen listener with the request Come to the window and later Listen! you… Now, lost on the darkling plain, cut off from Sophocles by time, with the Sea of Faith in retreat, and surrounded on all sides by confused alarms, he implores: Ah, love, let us be true to one another! His proposal is passionate, strengthened with all of Arnold’s poetic craft: onomatopoeia (ah) imperative tense (let us…), alliteration (love, let), assonance (us be true to one another) and marked with an exclamation. The most important word, though, is true – he needs his lover to provide truth, certitude and all those other things (light, love, joy, help for pain…) in a world that seems to only offer illusions, lies and false comforts. For Arnold to alight on love as the answer is not entirely surprising: in 1851 he married Frances Lucy Wightman and some commentators believe she brought him a measure of emotional security that he had lacked in his youth. It was while on honeymoon with his new wife that Matthew Arnold wrote this poem.

It turns out Dover Beach was a love poem after all.

Suggested poems for comparison

- Ulysses by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Like Arnold, Tennyson loved Greek myths and this is his reworking of Homer’s classic poem the Odyssey in which Odysseus (Ulysses) journey’s home after the Trojan War.

- The Buried Life by Matthew Arnold

In this poem, Arnold describes living in a world dulled of sensation, and explores the search for meaning that he believes lives inside all of us.

- Consolation by Matthew Arnold

Beginning ‘Mist clogs the sunshine’, you’ll see some of the same themes at play in this poem, also by Matthew Arnold: the idea that the old world is dying but the new is not yet born; the feeling that knowledge and truth is just out of reach; a vision of a confused and obscured landscape.

- Porphyria’s Lover by Robert Browning

Another poem that makes exceptional use of pathetic fallacy, Browning’s masterpiece is shocking and surprising in equal measure. Like Arnold’s poem, this work explores the contradictions of living in the Victorian Age, this time by examining conflicting attitudes towards prudery, transgression and morality.

- Look We Have Coming To Dover by Daljit Nagra

Under an epigraph from Dover Beach, Nagra presents a Britain where the land has become polluted and ugly – not because of the withdrawal of religion, as Arnold imagined, but because of yobbish hostility and fear of outsiders. Nagra, who’s parents came from Punjab to England in the 1960s, reimagines language as much as he does landscape in this poem that buzzes with all kinds of transformed words.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Dover Beach at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the Pathetic Fallacy

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What did you think of this analysis of Matthew Arnold’s poem? How do you express the philosophical ideas in the poem? What is your understanding of the powerful final stanza? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

A poem apt to modern readers, who also live in an uncertain world facing our own existential crisis.

Poetry Prof – not sure if I missed it in your fabulous analysis but wasn’t Arnold writing this poem on his honeymoon? Shouldn’t we expect someone whose just got married to be more optimistic about life?

Hi Johnny,

You’re quite right, the poem was written in 1851 during Arnold’s honeymoon and the unseen listener in the poem is probably his wife.

You might think that love would make Arnold more optimistic; but I’m not sure that optimism was too much in his nature. His wife Frances Lucy Wightman is thought to have provided him a measure of emotional balance – in stark contrast to his first love; a French actress named Marguerite, whom he took many adventurous trips to Europe to see and spend time with. Reportedly this was very out of character for Arnold and there were even suggestions that Marguerite may have been fictional (she wasn’t). After this relationship ended he would write: “Weary of myself, and sick of asking what I am, and what I ought to be.”

At least, at the end of Dover Beach, he calls for him and his wife to ‘be true to one another.’

I’m teaching this to a 9th grade composition class right now. Thanks for this stupendous analysis; I’ll be sure to use it in class.

Seems like one could profitably compare it to Hopkins’ Nature is a Heraclitean Fire–Hopkins like Arnold sees the impermanence of things, but unlike Arnold is able to locate higher cliffs of religious consolation that withstand the Heraclitean flux.

I was walking on the beach. Seagulls were bobbing on the calm sea. Tiny waves sounded on the shingle, making me think (because my mind tends to run in well-worn grooves) of Dover Beach. But this time the backdrop of planes and container ships made me think of climate change, and that the world was not as solid as it appeared on the surface and (gasp!) perhaps this was what Arnold meant. Queue your terrific essay. I had always assumed that it was the receding sea of (religious) faith that exposed a darkling plain, not receding faith in the entire edifice of Victorian progress. Perhaps Arnold put it like that to prompt a reading as about the new world ushered in by Darwinism, which would have been a more acceptable and popular subject than saying that absolutely nothing is what it seems.

Hi Rob,

This really is an epic poem, isn’t it?

Given Arnold calls it the Sea of Faith at one point, I’m sure that religion is in the mix there somewhere, but as you say, faith isn’t only religious – I love your phrase ‘receding faith in the entire edifice of Victorian progress.’

Related to emerging Darwinism, I was reading about clergyman Charles Kingsley (who wrote The Water Babies) and the way he embraced Darwin’s Origin of Species; it turns out it was surprisingly well received by members of the Victorian clergy who had less problem with ideas of evolutionary biology than we might imagine.