Thomas Hardy’s poem is touching – but also troubling when he rewrites the past.

“…the finest and strangest celebrations of the dead in English poetry”

Clare Tomalin, author of The Time-Torn Man, on Hardy’s ‘Emma Poems’ (1912 – 1913)

It’s a story as old as time: boy meets girl; boy and girl fall in love; boy and girl marry; man and wife grow older and crankier; man falls out of love with wife; wife goes to live in the attic; man hangs out with younger woman (38 years younger to be precise); wife dies; man regret his callous treatment of wife; man writes sequence of poems dedicated to the wife he neglected for so many years; man marries younger woman; man hears ghostly voice of his dead wife calling to him. Believe it or not, that’s basically the backstory to today’s poem. The man is Thomas Hardy; the woman is his wife Emma Hardy (nee Gifford) – and The Voice is one of eighteen poems written in a feverish haze of grief, guilt and regret in the space of only a few months after she passed away:

Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me, Saying that now you are not as you were When you had changed from the one who was all to me, But as at first, when our day was fair. Can it be you that I hear? Let me view you, then, Standing as when I drew near to the town Where you would wait for me: yes, as I knew you then, Even to the original air-blue gown! Or is it only the breeze, in its listlessness Travelling across the wet mead to me here, You being ever dissolved to wan wistlessness, Heard no more again far or near? Thus I; faltering forward, Leaves around me falling, Wind oozing through the thorn from norward, And the woman calling.

The story of Thomas Hardy’s meeting with his first wife, Emma Gifford, could have been ripped straight from the pages of one of his own blockbuster novels.

Before his career as a successful writer, Hardy was an assistant architect and, in 1870, was sent to Cornwall to work on the restoration of a small parish church. On arrival at the property, the rector himself was sick (bed-bound with gout) and his wife was glued fast to his bedside. So Hardy was received by Emma, the rector’s sister-in-law, who entertained him while her parents were indisposed. Hardy left this meeting smitten by the ‘magic’ of love at first sight.

Rather than blossom into a beautiful romance, though, this story quickly lurches into melodrama.

Their relationship was beset with problems, even before they married four years after they met. He lived in London, she in Cornwall – four train journeys away at the time. Her parents disapproved of the match (she was his social superior) as did his. After marrying, they moved to London where his literary success somewhat overshadowed her own, and she never truly took to life in the Big Smoke. The couple remained childless (some sources even debate the consummation of their marriage) and Hardy sought emotional comfort in the company of other women. Reading this, you might find it incredible that they remained married for 38 years! Eventually, though, their differences became intolerable and they became estranged. Emma kept her own room in the attic of their Dorset home, and Hardy spent more and more time in the company of other women such as Florence Dugdale (almost 40 years his younger and who would become his second wife).

As Hardy was an intensely private man who, quite incredibly for somebody who set such great store in the written word, would burn many of Emma’s documents (including a manuscript tantalisingly titled What I Think of My Husband like a celebrity kiss-and-tell that might have spilled all Hardy’s secrets; Florence, possibly acting out of jealousy, would later also destroy much evidence) it is hard to know all the ins-and-outs of their strange marriage. In The Time-Torn Man, a biography of Hardy’s life, Clare Tomalin argues that Hardy ‘was not an easy man to like’ and that he ‘coldly neglected’ Emma. On the flip side Emma might have been spoiled and may also have misled him about her intentions in order to secure a marriage that gave her access to the literary world. Other sources contain rumours of her suffering delusions, complete with secret visits to asylums and hospitals. It’s possible that there’s a gothic twist to their story, a-la Mrs Rochester from Jane Eyre or Charlotte Perkins’ The Yellow Wallpaper.

Then, in 1912, Emma suddenly died.

Despite the difficulties between them, it’s not hard to imagine how the death of someone to whom he had been so close might have struck Hardy. Emma’s passing prompted an outpouring of creativity; his most acclaimed poetry (a sequence now known as his Poems of 1912 – 1913) were composed in the months after her death. The Voice is an elegy depicting a grief-stricken speaker (an avatar for Hardy himself) who believes he can hear the ghostly sound of his recently-deceased loved-one calling out from beyond the grave (call to me, call to me provides an echo of the voice he hears; the repetition of this phrase is appropriately creepy and unnatural). The voice, which slips in and out of focus, is the poem’s central motif and most important symbol, carrying the weight of Hardy’s grief and activating his memories of their early relationship. The poem is, until the devastatingly dislocating final stanza, unashamedly nostalgic about the past, glossing over the unfortunate intervening years and seeking to return to a time of pure happiness, when Thomas Hardy and Emma Gifford first met.

The first words of the poem are forthright in terms of expressing grief; Hardy tells us straight that he missed his wife (the unnamed woman in the poem is, we know, Emma). But, it’s pertinent to ask, which ‘version’ of his wife does Hardy miss? Most of the poem is in the past tense – he misses the young, unchanged Emma from before they were married:

Saying that now you are not as you were When you had changed from the one who was all to me

Although the syntax of these lines is a little hard to unpick, through contrast between now and were you can work out that this is Emma from the past, an Emma who hasn’t existed for many years. In Hardy’s imagination, the first thing she does is apologise for growing older! She admits that she (you) was the one who had changed, tacitly accepting the fault for all their family dramas. We shouldn’t forget that Hardy himself authors the words attributed to Emma in The Voice, and a healthy degree of cynicism about what she says here is probably a good idea.

After hearing this strange voice, he asks (or rather demands) Emma to show herself: Can it be you that I hear? Let me view you, then. I don’t blame him for this – if I heard the faint voice of someone I knew to be dead emanating from thin air, I might like some proof I wasn’t going mad myself. The faint voice has acted like a Proustian Moment, a sensory trigger that unlocks other memories (named after French author Marcel Proust, who’s novel In Search of Lost Time is told entirely as a flashback triggered by the taste of a madeleine cake). Hearing her call to him, Hardy is transported across the gulf of years back to when they first met. The second stanza gives us the poem’s most powerful visual image: her blue gown is a symbol of the past (it is described as original) and the colour pops vividly, contrasting against the maudlin backdrop of the present day which is characterised by a damp, wan (meaning ‘drab’ or ‘colourless’) landscape.

More clues that the woman Hardy misses is not actually the woman who died only a few short weeks ago are hidden in the second stanza. There’s a noticeable contrast between Emma’s passivity and Hardy’s activity: he moves (when I drew near to the town; faltering forward) while Emma is stationary (standing; where you would wait for me). His tone of voice in stanza two slips easily into the tone of command (the position of the verb, let, at the beginning of a sentence creates the imperative tense, also called the command tense). Now she’s gone, Hardy is able to reconstruct an ideal relationship that is traditionally gendered. She’s a lot more pliant, demure and agreeable in his memory than she may have been in life. Whether intentionally on Hardy’s part or not, the poem explores how people, in times of sadness or when life isn’t going very well, tend to romanticise the past. In all honestly, the past was probably no better than the present – but we can twist our own recollections to reassure us that we were happier in a semi-imaginary time that conforms to our secret prejudices and preferences. When our day was fair erases anything unpleasant about the past and phrases things the way Hardy would prefer them to have been.

Whereas the structure of stanzas one to two move from the aural to the visual, stanza three makes an abrupt U-turn, pivoting about the word or and unfolding as one long question, indicating doubt as to whether the voice is real or only a hallucination brought about by grief and regret. There are two notable uses of diction in the third stanza. Firstly, dissolved: this word describes the evaporation of the vision of Emma; acts as a poetic metaphor for somebody dying; suggests that Emma’s unseen presence exists in the air around him – as any budding scientist knows, when solutes are dissolved in a solvent they are not really gone, they simply change state and become invisible. The second interesting diction is wistlessness. (Although ‘wistless’ has precedent in a poem from 1796 called Joan of Arc by Robert Southey, Hardy’s poem contains the first known use of wistlessness.) It means ‘unable to be observed’ and, combined with dissolved, suggests that, even though his rational mind knows that the voice is not real and Emma is gone, he is unable to fully let go of the possibility that there may be some trace of her left in the world. In an early draft of The Voice, Hardy used the word ‘existlessness’ instead of wistlessness, which would have removed the interesting suggestion that a part of Emma – her voice, or a ghostly image – might still linger in the living realm.

In common with other famous Victorian writers fond of walking (walking was both physical and mental exercise) Hardy sets his poem during a walk through the countryside, a landscape that, now Emma has gone, seems pale and lacking in vitality. You might have recognised pathetic fallacy, by which human emotional or psychological concerns are played out in the natural world. The wind blows ‘listlessly’ (Hardy nominalises the words ‘listless’ and ‘wistless’ into listlessness and wistlessness), meaning ‘without energy or enthusiasm.’ The mead (an archaic word linked to ‘meadow’) is wet, connoting tear-soaked grief, and everything is wan, meaning colourless.

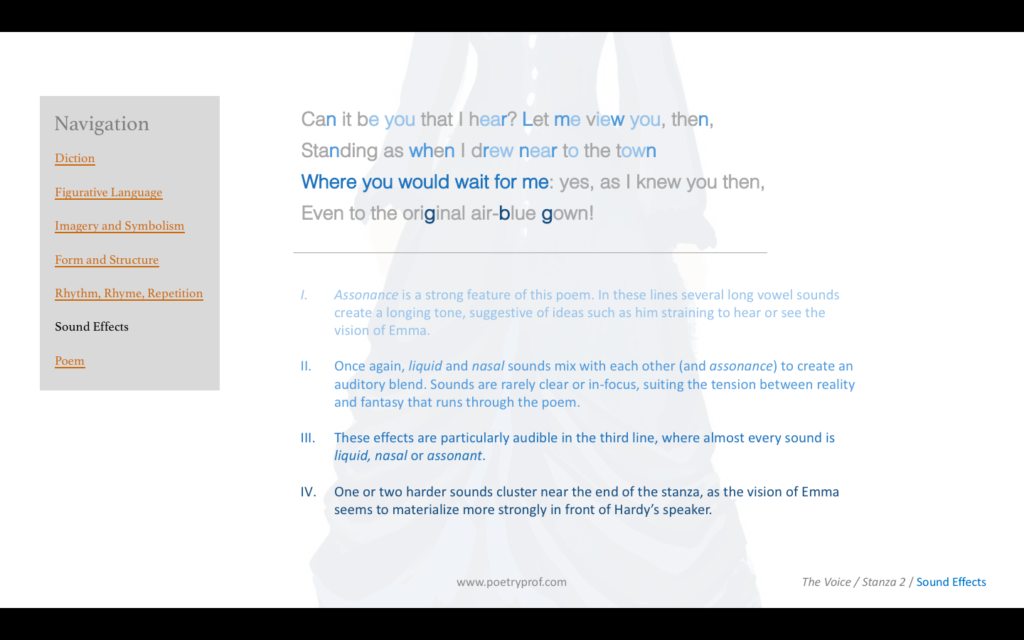

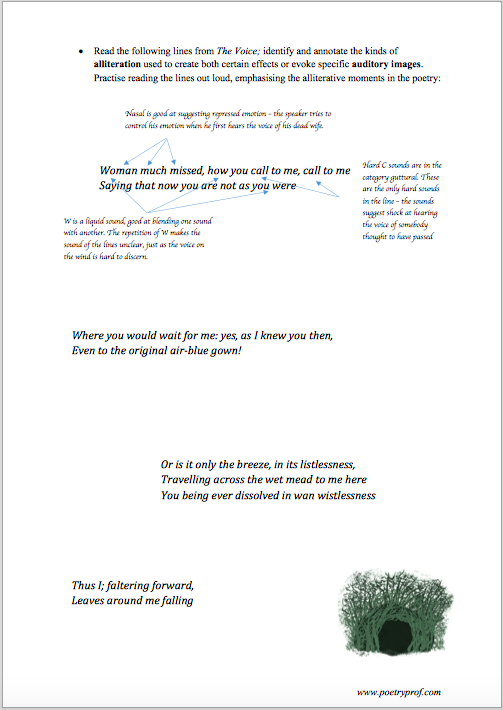

Unsurprisingly in a poem with an audible motif, The Voice is an absolute masterclass in the use of sound; alliteration and consonance powerfully transport Hardy’s shifting sense of certainty and uncertainty about the reality of his experience. Happily, we don’t have to read much further than the first line to discover much of what there is to know about sound in the poem:

Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me, Saying that now you are not as you were

Before we go on, you’ll need to be familiar with a couple of technical words that describe different types of alliteration. Broadly speaking, there are eight types, or categories, four of which can be seen at play in the first lines. The most obvious is liquid. Made with the letters L, W and R, liquid is very good at creating a fluid sound (like water, which is where it gets its name). The sound is rarely clear or well defined, it can sometimes be hard to hear the presence of liquid alliteration at all. Look carefully at the first two lines and see if you can find all the L, W or R sounds (although alliteration counts only letters at the beginning of words, consonance counts all repeated uses of the same letter. For the sake of this exercise, you should understand ‘alliteration’ to mean consonance).

The second category is nasal, created using M and N sounds, which shares the same obscure, woozy quality of sound as liquid; it’s hard to discern lots of nasal sounds clearly as they blend readily into one another and into other sounds. The effects of nasal and liquid are only amplified when combined and you can go back to the lines above and count both types together. Because nasal sounds are created by holding air in the nose and behind closed lips, another common effect of nasal alliteration is to suggest suppressed emotion, (close your eyes and make long M and N sounds to discover what I mean). This effect is certainly intended at the start of the poem; and the contrast between controlled and uncontrolled emotion can be seen in the contrast between the first three stanzas and the last.

Thirdly, you’re probably already familiar with sibilance. Created using S or SH sounds, sibilance is easier to discern than liquid or nasal, but still soft and ‘frayed’ at the edges. As well as clearly evoking the sound of wind blowing, sibilance combines with liquid and nasal to thicken the auditory soup of the opening lines, and contributes to the impression that the voice heard by the speaker may or may not be real. Once you add assonance into the mix (assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds including Y), you have a complete auditory image of a ghostly voice that seems to oscillate in and out of hearing, at times mixing with the wind; simultaneously, deep, low vowel sounds mix well with nasal to evoke the mournful tone of grief and regret.

The form of the poem is stanzaic, which means each verse follows the same patterns of rhythm and rhyme. Let’s look carefully at the poem’s rhythm or meter. The best way to do this is actually to listen rather than ‘look’: speak one of the first four stanzas out loud and hear (or ‘feel’) where the emphasis falls on particular syllables. Have you noticed that the first syllable of each line is always a heavier beat? This heavy syllable (or stress) is followed by two light ones, before the pattern begins over again. Read a line or two with exaggerated slowness to discern this pattern for yourself: stressed-unstressed-unstressed, repeated four times. Take a look at the third stanza again, now with accents marked:

/Ōr is it /ōnly the /brēeze, in its /līstlessness

/Trāvelling a /crōss the wet /mēad to me /hēre,

/Yōu being /ēver dis /sōlved to wan /wīstlessness,

/Hēard no /mōre a/ gāin far or /nēar?

A pattern of three syllables arranged stressed-unstressed-unstressed is called a dactyl, so the poem’s prevailing meter is dactylic tetrameter. This is a relatively unusual meter to employ for the entirety of a poem. It works particularly well to generate a sense of movement, which you can connect to all kinds of movements in the poem: in the first couple of stanzas it creates an echoing effect, as if Emma’s ghostly voice is strong one moment and fading the next; dactyls summon the movement of the breeze… travelling across the wet mead; the implacable passing of time (the regularity of the meter metronomically counts down the years); the lilting gait of Hardy’s walking as he returned to town to find his wife waiting for him; and – powerfully – the sudden faltering lurch as the speaker stumbles forwards in the final stanza. The pattern of a dactyl is such that unstressed syllables are at the end; lines of poetry that end with unstressed syllables are written in falling rhythm – given that Hardy ends his poem by having his speaker stumble (faltering forward) – this is one of those happy times where form and content are perfectly matched.

(‘Ah, but’ – I hear you state knowingly, like a disembodied voice carried by the wind – ‘the second and fourth lines don’t end in unstressed syllables – these lines are truncated, so the final syllable is stressed.’ If one of these ghostly voices is yours, give yourself a pat on the back. You’re right and, actually, the alternating pattern of falling and rising rhythm is not uncommon. If it helps, think that the last two syllables are still there, but invisible – just like Hardy imagines his wife might be. The poem asks the question as to whether the voice is real or a hallucination and this aspect of rhythm can be seen as part of this tension: is she there, or not? In fact, as you can see from the fourth line here, there are other disruptions to the prevailing meter in the fourth line of each stanza. Sometimes the foot is only two syllables long (patterns of two syllables, arranged stressed-unstressed are called trochees) and sometimes it’s hard to scan the rhythm smoothly. Any rhythmic disruption contributes to our understanding of the speaker’s uncertainty; is the voice on the wind real or a product of his imagination? Is he buckling under the weight of guilt and regret at his long estrangement from his wife? Given Hardy was in his seventh decade when he wrote The Voice, is he thinking of his own impending death?)

All these ideas come together in the incredible fourth stanza where the poem achieves most of its emotional power. Whether or not the voice is real, suddenly regret, loneliness and grief overwhelm Hardy’s speaker. The switch from past to present tense suggests that only now has the full force, the true realisation that she’s gone forever, hits him. Pathetic fallacy is important again, leaves around him mirror his stumble (faltering forward) in the way they are shown falling to the ground. And suddenly the wind, a thin, weak element in stanza three, thickens powerfully, creating a physical impediment:

Wind oozing through the thorn from norward

Once again, Hardy’s poetry delivers a masterclass in sound. Look how fricative F and TH, liquid W, nasal N / M and assonant O suddenly condense and thicken – thorn from norward contains all of these effects in the space of just three words – recreating both the sound and texture of the wind that bites painfully (thorn relates to any spiky tree or plant that is painful to the touch; norward is an archaic form of ‘northwards’; winds from the north bring a touch of arctic ice). The effect of this ghostly wind is both literal (faltering suggests how the legs might become unexpectedly weak) and figurative; faltering forward suggests how difficult it might be for Hardy to find his way through the remainder of his life without Emma’s reassuring presence. Whatever you think of Hardy’s revisionist memory in The Voice, the two continued to enjoy each other’s company (they bicycled out and even went on holiday together) late into their relationship.

As if the voice just won’t go away, the last line echoes the first meaningfully. Poems that end where they began are written in loop composition. The final line suggests to me that, from here forward, his thoughts will continue to circle back to Emma; her unseen voice – and all the guilt and regret at wasted time spent apart it represents – will hereafter haunt him for the rest of his life.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Phantom Horsewoman by Thomas Hardy

Written about and dedicated to Emma, this is the last of Hardy’s Poems of 1912 – 1913. Like The Voice, it depicts his wife as he likes to remember her; young, carefree, riding her horse along the rugged Cornish coastline. The line Time does not touch her betrays Hardy’s desire to keep her forever young in his memory.

- Ghost by Cynthia Huntingdon

This fantastic poem flips everything about Hardy’s The Voice around. For one, it’s told from the perspective of the ghost; for another, it’s about the present (or even maybe the future) as well as the past.

- Annabel Lee by Edgar Allen Poe

I was thinking about recommending The Raven because of the spine-tingling use of voice in this poem too; but I settled on the less well-known Annabel Lee in which Poe’s speaker remembers a woman who has died.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Voice at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on examining types of alliteration and consonance.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for revision or a recap lesson.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Thomas Hardy’s poem? Do you think the criticism of his view of history is warranted or a little harsh? What impact does the last stanza have on you? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.