Notice for anyone studying CIE English Literature: this poem has been withdrawn from the current selection (2020 – 2022) and been replaced with The Planners by Boey Kim Cheng. You can read my take on The Planners here.

Watch as James K. Baxter‘s eponymous Farmhand refuses the call to adventure in this poem from New Zealand.

“I never get sick of reading Baxter’s poems, he’s a major voice – he’s up there with Beethoven, and Dylan, and Bach…”

Farmhand, written in the 1940s, is a subtle description of a character on the cusp of adulthood. He’s an awkward teenager; he wants to make his way in the world but hasn’t yet developed the necessary confidence, skills or sophistication to leave his comfort zone. In some ways – notably his physical size and strength – he’s outgrown his childhood self. But in others (his slow-growing mind) he’s still trapped in the childish world. James K. Baxter, from New Zealand, died aged only 46 after both battling with alcoholism and converting to Catholicism. After he left university he spent many years working on farms, so it’s tempting to read the poem in Baxter’s own voice, a speaker looking back on adolescence with mixed feelings: regret at missed opportunities; nostalgia for a more innocent way of life he may have outgrown.

You will see him light a cigarette

At the hall door careless, leaning his back

Against the wall, or telling some new joke

To a friend, or looking out into the secret night.

But always his eyes turn

To the dance floor and the girls drifting like flowers

Before the music tears

Slowly in his mind an old wound open.

His red sunburnt face and hairy hands

Were not made for dancing or love-making

But rather the earth wave breaking

To the plough, and crops slow-growing as his mind.

He has no girl to run her fingers through

His sandy hair, and giggle at his side

When Sunday couples walk. Instead

He has his awkward hopes, his envious dreams to yarn to.

But ah in harvest watch him

Forking stooks, effortless and strong –

Or listening like a lover to the song

Clear, without fault, of a new tractor engine.

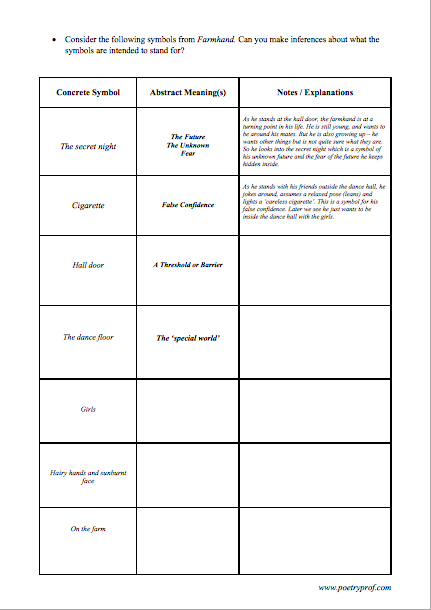

Sometimes it can be fun to read one form of literature, such as a poem, through the prism of another, such as an adventure story. And that’s exactly what we are going to do today: examine Farmhand through the lens of Joseph Campbell’s work The Hero of a Thousand Faces. If you’re familiar with this work, you’ll recognise a particular moment from the ‘Monomyth’ (otherwise known as the ‘Hero’s Journey’) in Baxter’s poem. In order to research and develop his theory, Campbell traced the narrative journeys of thousands of literary protagonists from childish innocence and naivety to worldly experience and skill. He theorised that a hero-in-waiting undertakes two simultaneous journeys: internal and external. In order to learn and grow a person must physically venture into the wider world. Journeying – encountering obstacles, dangers, challenges – brings considerable risk; but also brings the experience necessary to become a hero. Campbell’s theory can be applied to any number of stories from Homer’s Odyssey, to The Tales of King Arthur to Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games to Dreamworks’ Kung Fu Panda. Reading texts with knowledge of the Monomyth in the back of your mind often brings new possibilities of meaning and symbolism. In this poem, contrasting the Farmhand’s external appearance – either indifferently joking with his friends or physically strong – with his inner emotional turmoil will open up all kinds of understandings.

What propels someone to leave the comforts and safety of the ‘ordinary’ world in the first place? Well, the Monomyth can be understood as a metaphor for growing up, leaving one’s home and becoming a fully-fledged person able to cope and flourish in the adult world. Before a person is able to embark on this journey, though, there is a moment of doubt. Imagine an eighteen-year old suddenly realising they won’t ever come back to their parents’ house and now they have all the bills to pay and washing-up to do for themselves. Campbell calls this moment the ‘Refusal of the Call.’ Remember the bit in Star Wars when Luke Skywalker tells Ben Kenobi, “I can’t go with you to Alderaan, I’ve got too many chores to do”? Often because of fear, ignorance or self-doubt the hero is not able to immediately begin their journey. Watching the Farmhand at the doorway, it’s clear he is paralysed by doubt. Baxter gives a clue for us to speculate about where his reluctance comes from: the music tears… an old wound open. It’s a reasonable inference to make that fear of rejection, scorn, bullying, or the cutting laughter of others are behind the pain in his past.

In Farmhand, the ‘ordinary’ world is the farm on which our hero feels most comfortable. In this world he is in his element. See him forking stooks, New Zealand dialect for using a pitchfork to fling rolled up bales of hay over your shoulder or to stack them on a a truck or in a barn. He is effortless and strong, which he would need to be as forking stooks in the hot sun all afternoon is some feat of stamina! We are invited to be impressed as we watch him – check out the onomatopoeia, ah, connoting admiration. Always, the Farmhand is associated with the natural world. In the third stanza, his face is red and sunburnt from long hours outside, his hands are hairy, almost like an animal. Even his hair is sandy; hair will turn this colour when exposed to the sun, but also the word is linked to soil and earth. The most direct association is a simile that compares his mind to slow-growing crops. Actually, the word ‘slow’ (slow-growing, slowly) is repeated twice, emphasising his plodding, unsophisticated character; assonance (the repetition of certain vowel sounds, underlined) plays a part here as well – listen to those long, round O sounds which create the auditory impression of something slow and plodding. Awkward from line 16 is the most apt word to describe him in any other context apart from on the farm.

Therefore, when he’s at the cusp of the ‘special’ world (the door is a symbolic passageway connecting the two worlds) it is not surprising that, behind his veneer of confidence, there lurks considerable awkwardness. When you see him light a cigarette imagine him doing so indifferently, even a bit arrogantly. Careless, leaning and telling some new joke all convey a certain nonchalance as if he couldn’t care less about where he is and who might be watching. But it’s all an act. His eyes betray the truth: always his eyes turn to the dance floor and the girls. The dance floor symbolises the special world – here, at the portal, you can feel his reluctance to cross over. He remains poised on the threshold, physically paralysed, looking out into the secret night (another symbol for the temptations of the unknown). Enjambment (lines that run from one to the next with no pause at the end) features heavily in this poem. The way almost every line staggers and ‘falls’ into the next helps convey the confused whirl of thoughts and feelings he hides behind his nonchalance. In stanza 4, the only stanza made of more than one sentence, when one thought finishes and another begins, the placing of the full stop does not match the arrangement of lines on the page. In poetry, a break in the middle rather than the end of a line is called a caesura.

Joseph Campbell noticed that in stories a hero’s success is usually rewarded: Prince Charming rescues the damsel in distress; Harry Potter revives Ginny; Kung Fu Panda realises the wisdom hidden in the scroll. Campbell termed this stage of the journey ‘Seizing the Sword’. The reward is a symbol that the hero has mastered the requisite skills and amassed the experience necessary to flourish in the ‘special’ world. What is the reward that tempts our Farmhand away from the safety of his farm and into a world of danger? It’s pinpointed in the second stanza and, if you know any teenage boys, it won’t surprise you that the answer is girls! Their symbolism is highlighted through the simile drifting like flowers, making them visually beautiful, extraordinary. The fourth stanza develops more detail about the Farmhand’s hopes for this reward: tactile imagery replicates the sensation of her fingers through his sandy hair that he so desperately wants. He sees others giggling as they walk arm in arm on Sundays (traditionally a rest day when he would not be working, and perhaps at a loss) and is envious. Negation deepens the sense that something is missing from his life: he’s not made for dancing and he has no girl. The deep longing for companionship is implied through diction, yarn, meaning to talk in a long, relaxed manner. Incidentally, this word from the lexical field of storytelling is another hint as to the underlying presence of the Monomyth in Baxter’s ‘story’ of the Farmhand.

The form of the poem comes into its own in the marvellous final stanza. It’s like when we’re back on the farm everything slots comfortably into place. Even just looking at the shape of the lines on the page, you can see how the final stanza is the most ‘comfortable;’ all four lines are nearly the same length, without the funny staggering of long and short that comprised most of the other quatrains. Take the rhyme scheme as a further example; we’ve had waking/breaking and a tenuous half-rhyme in cigarette/night, but not much else. Suddenly, the sounds in the final stanza resolve into near-perfect rhymes: him/engine and strong/song. The sonorous, ringing sound of the tractor engine, as heard through the farmhand’s ears (listening like a lover), is evoked through nasal N, M and NG sounds. The ease and lightness he feels away from the pressure of the special world is communicated through a blend of quick, light K, L and T sounds: effortlessly, listening, like, lover, clear, without fault, tractor. Symbolism again comes into play: just as the special status of the dancing girls was marked with a simile, his tractor is described like a lover.

We noted before that the poem is narrated to us by a speaker; so who is he speaking to? Well, the first word of the poem is actually addressed to you! The reader is explicitly invited, in both the first and final stanzas, to watch the Farmhand: you can see him and watch him. It is clear through the positioning of these references – one outside the dance hall, one on the farm – that we are being asked to compare him both in and out of his natural environment. It’s as if we are transported back in time to stand alongside the speaker and see the Farmhand for ourselves. The focus on looking and listening has been subtle, but insistent: eyes turn, he watches, listening like a lover. While the Farmhand is but one example, the archetype he represents is a metaphor for any young person who, as they reach the cusp of adulthood, experiences doubt, fear and reluctance to leave the protection of a familiar environment. Baxter thinks you will recognise a part of your own experience in that of the Farmhand’s – if you look carefully enough.

Sugested Poems for Comparison:

- The Flight of Youth by Richard Henry Stoddard

This poem makes an interesting comparison to Baxter’s Farmhand. Both poems explore the idea of growing from youth to adulthood, but Stoddard’s poem laments what is lost in the past instead of looking at what might be won in the future.

- In Mrs Tilscher’s Class by Carol Ann Duffy

Another poem set on the cusp of adolescence, the dangers and fears of the adult world are powerfully implied by the final image of the sky breaking open into a thunderstorm.

- Death of a Naturalist by Seamus Heaney

This brilliant poem, set almost entirely in a flaxy swamp (Joseph Campbell’s ‘special’ world again), is a perfect companion-piece to Farmhand. Here too, the central character is not quite ready to leave their comforting childhood world. At the end of the poem, faced with a colony of grotesque giant bullfrogs, the speaker turned, and ran.

- Wild Bees by James K. Baxter

While his career was cut untimely short, he was still a remarkably prolific poet; and in my opinion, Baxter never wrote a dud. I was going to recommend Summer 1967 here as, like Farmhand, it deals with ageing (although from the point of view of someone passing into old age). But instead, here’s Wild Bees, for no other reason except it’s my favourite. All the folly of youth – the adventure, wildness and stupidity – is laid bare in this poem about boys stealing honey from a beehive.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Farmhand at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Symbolism.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you recognise this poem as a rites of passage story? Or did you interpret other meanings into the presentation of the farmhand? What do you think caused the wounds in his mind? Share your ideas with others, start a discussion, or simply let us know if you enjoyed reading this post in the comments section. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Poetry Prof,

According to Cambridge (https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/Images/606873-2022-syllabus-update.pdf), this poem has been replaced with ‘The Planners’ by Boey Kim Cheng for the CIE IGCSE exams in 2022. Would you be able to write an analysis for that poem, please? Thank you!

Hi James,

Don’t worry – a Planners blog is incoming. Watch this space!

Thank you, I’m looking forward to it already! Your blogs are always so, so helpful!

This is highly enlightening. How do I get complete analysis on the literary devices of the poem?

Hi Eugene, thank you for your comment. You can take a look in the shop and find the study bundle for this poem. One of the resources is a detailed powerpoint with annotations on every line, including comments on figurative language, imagery, symbolism, rhythm, rhyme, repetition, sound patterns and any techniques unique to this poem.