Allen Curnow suggests that there’s a right time to die in this tough, but rewarding, poem.

“He wrote of things on the edge of our vision and he made them clearer for us.”

Sir Paul Reeves, Governor-General of New Zealand 1985-1990

You Will Know When You Get There is from Curnow’s 1982 collection of the same name, full of poems describing memories of his youth and family. One critic wrote in an obituary (Curnow died in 2001 at age 90) that this book was best known for dealing with “a creeping sense of the nearness of death.” It would be an apt description of this poem – except here, death doesn’t so much creep as hurtle forwards at one-hundred miles per hour.

Nobody comes up from the sea as late as this

in the day and the season, and nobody else goes down

the last steep kilometre, wet-metalled where

a shower passed shredding the light which keeps

pouring out of its tank in the sky, through summits,

trees, vapours thickening and thinning. Too

credibly by half celestial, the dammed

reservoir up there keeps emptying while the light lasts

over the sea where ‘it gathers the gold against

it’. The light is bits of crushed rock randomly

glinting underfoot, wetted by the short

shower, and down you go and so in its way does

the sun which gets there first. Boys, two of them,

turn campfirelit faces, a hesitancy to speak

is a hesitancy of the earth rolling back and away

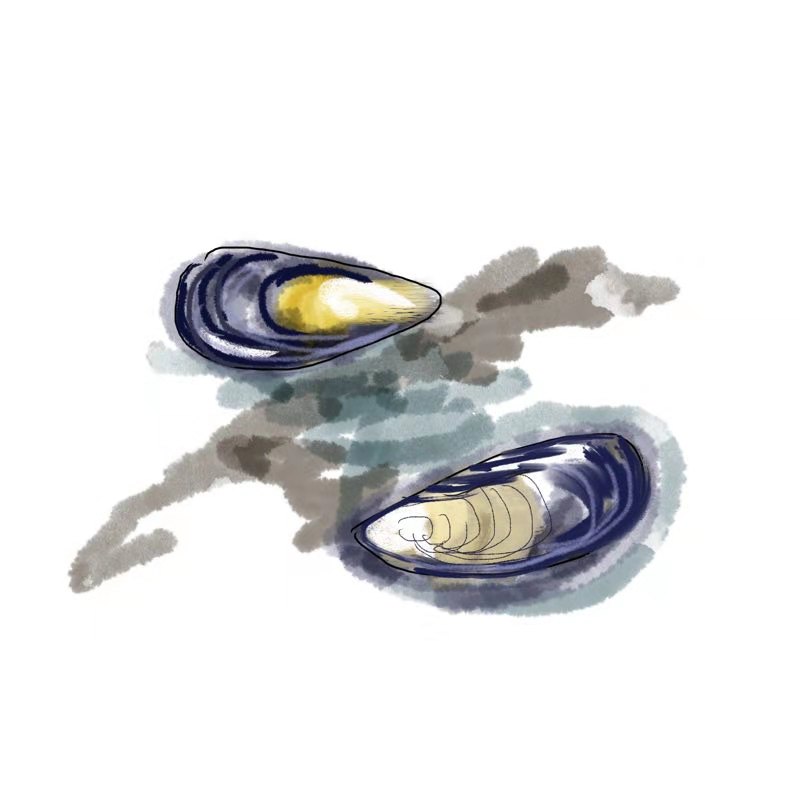

behind this man going down to the sea with a bag

to pick mussels, having an arrangement with the tide,

the ocean to be shallowed three point seven meters,

one hour’s light to be left, and there’s the excrescent

moon sponging off the last of it. A door

slams, a heavy wave, a door, the sea-floor shudders.

Down you go alone, so late, into the surge-black

fissure.

The poem describes the last few hours of a man’s life as he takes a favourite walk down to the seashore to pick mussels. It seems that he knows he is soon to die and wants to get there before it’s too late. Perhaps he wants to die in his favourite spot, or he wants to see the sea for the last time. At the end of the poem he wades out into the sea and into a surge-black fissure, a deep crack in the sea floor, like a canyon or abyss. It’s a direct metaphor for death: once you fall into that fissure there is no coming back.

When the poem begins it’s already ‘late… in the day’ which you can understand to mean late in the man’s life. Look how, in the first few words, the component of time is introduced into the poem. We’ll be getting back to that very soon. In the meantime, watch as he begins his final walk down a steep path, which is made slicker and more treacherous by the rain. He has an arrangement with the tide which will be at just the right depth for him to wade out into the sea. What is this arrangement all about? Well, the first couplet (Nobody comes up from the sea as late as this/ in the day and season and nobody else goes down) introduces a rather interesting idea: nobody goes ‘down’ at any time other than the correct one – there is a time for everybody to live and everybody to die. Before Curnow worked for the BBC in England, he studied theology in New Zealand and planned to enter the church. While he abandoned his religious practice to pursue a career in journalism, it’s not a huge stretch to think that as somebody gets older, they might contemplate whether or not their time of death is preordained.

I get the feeling that the man in the poem is aware of his approaching death. His concern is to meet it at the right time and in the right manner. Just as we all, ultimately, have to face death in our own way, the first couplet makes it clear the man is by himself, it’s his time alone. This idea is reiterated in the final stanza: Down you go alone. That also explains the hesitancy to speak of two boys camping on the beach as he passes by: they symbolise youth, which has a revulsion of old age. By this point in the poem his journey has become pretty metaphysical anyway: their reluctance to acknowledge him is echoed by the hesitancy of the earth rolling back and away behind this man. This line reminds me of a Sylvia Plath poem, Suicide on Egg Rock: as she watches a man prepare to throw himself into the sea, he turns his back on the world, positioning everything else in the poem physically behind him, separating the living from the (soon-to-be) dead.

To be honest, even at the start this was never just a comfortable evening walk. Pretty quickly we get the feeling that the path down to the beach is steep and treacherous. We’ve already seen the word down (to begin with, the sense of downward motion is counterbalanced using juxtaposition: nobody else goes down / Nobody comes up. This equilibrium doesn’t last long though). Soon, the feeling of downward motion accelerates, becoming faster and wilder. The image of a man descending a steep cliff path and scrabbling down the last steep kilometre is quite powerful; the lurching downhill motion is accentuated by the wet road, which creates a sense of slickness on the road surface. (Reader Andrew has commented that in New Zealand wet-metalled refers to ‘road-metal’, the crushed stones used in forming a firm road surface, as opposed to an unsurfaced or ‘unmetalled’ road – thanks Andrew). Everything in this poem moves down: the man, the path, rain, the sun. The sense of downward motion is accentuated partly through repetition (…and down you go… this man going down to the sea… Down you go alone) and partly through enjambment as the poem careens from one line to the next, one stanza to another. Its arrangement in couplets seems entirely arbitrary as there are no end-stops to match the sense of the lines to the stanza arrangement; neither are there any capital letters marking the beginnings of the stanzas, so when you read the poem out loud the ideas from one verse fall into the next. The descent is both literal, as he heads down to the beach, and figurative: ‘up’ means life where ‘down’ means death.

There is a real sense of urgency to the man’s journey – he wants to get there before the light fades. Like the fissure, ‘darkness’ is a direct metaphor for death: when it’s dark, he dies. But he wants to reach the sea first – so he has to get there before the sun goes down. In narrative writing this race against time is called the ‘ticking timebomb’ technique; Curnow uses it brilliantly here to create tension. So at the start of the poem it’s still light – but not for long. Mentions of light are qualified so that it never really seems like there is much light left, for example: as late as this in the day; half celestial (which means he can half see the stars); while the light lasts. Other words describe the light as weak, for example: glinting.

One description of the light involves Curnow quoting from another poem, Ezra Pound’s Cantos, in which he wrote: ‘it gathers the gold against it’. The best way to understand this allusion is to replace the two its with ‘light’ and ‘dark’, so the line reads: ‘the fading light gathers its own golden colour against the coming dark’. Imagine watching a sunset: the light briefly becomes more beautiful, powerful and precious as the dark encroaches. Or stare closely at a candle as it burns to the end – notice how the flame settles and strengthens just before it goes out. The image also suggests the man armouring himself with the determination to prolong his life just that little bit longer, so he can reach his destination before dark falls. Actually, the sun drops below the horizon before the man can reach the beach (the sun which gets there first) and from this moment the light recedes more quickly. A campfire casts flickering light mixed with shadow and soon there’s only one hour’s light to be left. No wonder he personifies the moon not reflecting light, but selfishly absorbing (sponging off) the last of it, a thief robbing him of precious time to reach the tide-line.

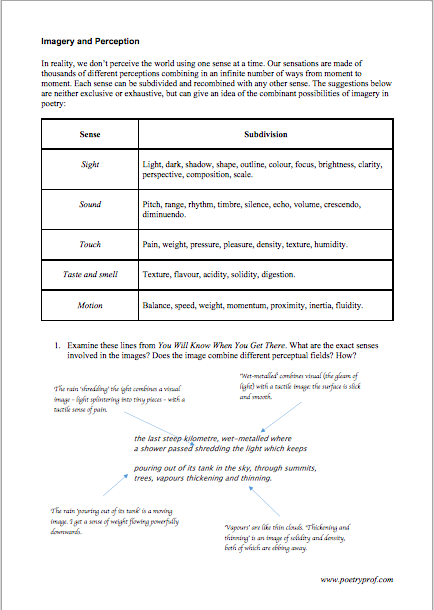

There’s another dimension to these light descriptions, some of which concern its ‘quality’, as if this late-in-the-day light is a brittle thing, easily broken. The third couplet describes a passing rain shower shredding the light, refracting it into a million broken pieces. This image is compounded later: the light is bits of crushed rock randomly glinting underfoot. I can picture him walking on a beach where every grain of sand is twinkling, catching the last little bit of dying light. Notice the position of the light relative to the man: it was above him, now it’s below him. It’s like he’s walking on a vista of stars. Briefly, the poem reminds me of one of those movie images where some tragic character faces the universe, the stars wheeling above and below, and comes to terms with their own mortality. The brittle, fractured quality of light in these lines may suggest the man’s feeling as he realizes his own death is imminent.

It’s also worth looking at the way the light interacts with the rain more closely. Curnow gives us a couple more images to ponder: the first is a reservoir up there keeps emptying; the second is the light which keeps pouring out of its tank in the sky. Both images suggest that we all have a store of time (reservoir, tank) that slowly drains away. The man is acutely aware that his store is emptying fast, like the last few grains of sand falling through an hourglass. In the second image Curnow employs synaesthesia to mix up the way we perceive this. Notice how the quality of rain (pouring) is transferred to the light itself. Remember, light has been conflated with time: the amount of light left in the day is the same as the time he has left to live. Water becomes a strong motif in the poem, present in the rain, the wet path, the reservoir and tank, the shower, the wave and, of course, the sea. Even the ground moves like water, rolling away from him like a receding wave. Through the element of water, Curnow suggests that the process of dying is a natural one; as rain falls from the sky and flows into the sea, so too do we slip easily from life to death.

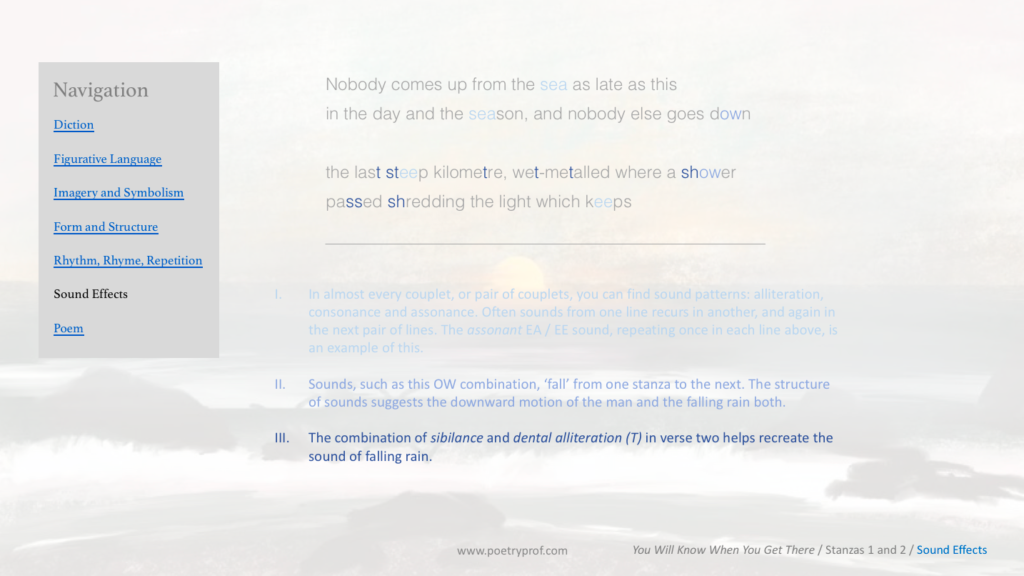

Above all, the sense of forward motion, that inexorable tumble towards the fissure, comes from the form and sound patterns of the poem. Curnow very deliberately employs consonance, assonance and alliteration, as well as half-rhyme and internal-rhyme, so that repeated sounds fall through the poem like rain, that shower… shredding the light again. In this example you can easily see the doubled SH sound. You can choose almost any stanza and hear Curnow playing with the possibilities of sound arrangements: sounds repeat themselves in one line, echo through a couplet and even trickle down from one stanza to the next. Take this section as an example:

a shower passed shredding the light which keeps

pouring out of its tank in the sky, through summits,

trees, vapours thickening and thinning. Too

credibly by half celestial, the dammed

reservoir up there keeps emptying while the light lasts

over the sea where ‘it gathers the gold against

it’.

Repeated sounds multiply and overlap. You can see how, just for example, the hard K in keeps multiplies in tank, sky and thickening. The TH in thickening was preceded by through and repeats in thinning. Through rhymes with too. Actually, while the poem has no rhyme scheme, this case of internal-rhyme is far from the only one – you can hear rhyming words scattered about like splashed raindrops: pour/vapour, reservoir/over, there/where. The quoted section finishes with ‘it’ – read on a few lines to find the light is bits and campfirelit. One of the most obvious instances of internal-rhyme comes at the very end when door is rhymed with sea-floor. There are many more for you to discover.

So what about that ending? Curnow gives us a sequence of metaphors mixed with literal language depicting the moment of the man’s death:

[a door] slams, a heavy wave, a door, the sea-floor shudders.

Down you go alone, so late, into the surge-black

fissure.

Death is figuratively a door that slams, suggesting there’s no way back. In reality this door is a heavy wave which submerges and drowns him. The metaphorical door returns in an ambiguous repetition: I like to think it’s the same door, seen from the other side. The sea-floor shudders could be figurative or literal. Finally, death is the surge-black fissure from which there is no escape. Curnow uses synaesthesia again here, connecting the colour black with the kinaesthetic word surge. It’s at this point that the poem’s tendency to address the poem directly to the reader, you, pays off. We are forced to contemplate the uncomfortable idea that one day we too will be in this moment. What I really like about the end is that, when it comes, the experience of death is very concrete – which may come as a bit of a surprise after the abstract meanings in the poem so far. But, like he said in the poem’s title, although death is a mystery to all of us, and no-one living yet knows what it is really like to die, one thing is for certain – you will know when you get there.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Time by Allen Curnow

If You Will Know When You Get There hasn’t put you off reading more Curnow, try Time. In a series of descriptive metaphors, this poem explores how we perceive and relate to time. And it’s much easier, I promise!

- Death Poem by Moriya Se’nan

Among Buddhist poets and monks in Japan, there is a tradition called jisei: the composition of a final poem a few hours before one’s death. This poem, translated from original Japanese, is a lovely example of this slightly known poetic tradition.

- Suicide Off Egg Rock by Sylvia Plath

In this poem, the speaker watches as somebody prepares to throw himself into the sea. All around him on the beach life is bustling, but he purposefully turns his back on the world. The poem interestingly implies that it is in the moments before death that he feels most alive.

- Protocols by Randall Jarrell

Be very careful with this poem – it’s devastating. Told from the point of view of children taken to different concentration camps, it is, not surprisingly, hard-hitting.

- Because I Could Not Stop For Death by Emily Dickinson

This poem is a great counterpoint to Curnow’s frenetic fall into the abyss. In Dickinson’s poem, Death is personified as a courteous gentleman who comes to escort you in a carriage with all due ceremony into the afterlife.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying You Will Know When You Get There at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to explore our bespoke study bundle for this poem. Normally costing only £2, you can try the materials for this poem for free. The bundle includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Imagery.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy Curnow’s exploration of what it might be like to die? Or did you find the poem a little confusing? Do you agree that there is a ‘right’ time for everybody to die? What did you make of the symbolism in the poem – the two boys who refused to speak with him, or the heavy door slamming? Share your ideas and suggestions for other readers in the comments section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Awesome commentary – love the way you guide us through the nitty gritty of this poem…

Hi John,

Thanks for your comment, we’re so glad you like the commentary. Hope to see you on one of our other poems soon.

Amazing commentary. though i just wanted to confirm if you are an IGCSE examiner

Hi Pranav,

Thank you for your compliment. No, I’m not an examiner. The blogs are not endorsed, but I hope you find them useful to read if you are teaching or studying the poems.

They are very helpful,

thank you,

Pranav

Your analysis is excellent, so I was wondering if you knew any sources for prose analysis?

Hi Advaita,

Thank you for your comment. Unfortunately, I haven’t given any thought to prose – Poetryprof is keeping me busy enough!

I was wondering if you could also provide us with sample IGCSE answers in the top bands

Hi, sorry, I have no plans to provide full sample IGCSE answers. But take a look inside the study bundles; there’s a sample essay plan, including fully written paragraphs to help work on style and provide some idea of appropriate content. There’s also loads of idea for how to comment on the poetic features in the PPT and accompanying work sheets. Hope that helps!

Thank you prof, I will do that.

Hey,

I was wondering if you will be publishing analysis on the IGCSE poems for 2020. There are already some (e.g. carpet weavers) but there are some which are not (e.g. Dover Beach, Old familiar faces, Time, Lament)

Hi Alex,

I’m working on a couple of those poems now (Dover Beach should be next). I try to post a new poem once every couple of weeks or so, so… watch this space.

Thank you very much. We need more heroes like you 🙂

I think ‘metal’, as in ‘wet-metalled’, refers not to the smooth shiny surface of a metal such as steel, but rather to road-metal, i.e. crushed stones used in forming a firm road surface (as opposed to an unmetalled, or unsurfaced, road). That’s consistent with New Zealand usage.

Hi Andrew,

Thank you so much for your comment – that’s great. I’m over the other side of the world in Britain, so great to learn something about New Zealand English. Will amend in the blog.

Thank you again!