John Clare gets maudlin when he falls in love with an unattainable woman.

“We can see his poetic impulse as something born of the wish to preserve as well as celebrate; even the most simply joyful pieces are soaked in… regret and unsatisfied longing.”

Andrew Motion, (Poet Laureate 2015 – 2019)

Love at first sight – do you believe it can happen? In John Clare’s poem First Love, the emotion strikes with sudden force, captivating and incapacitating the speaker till he can do nothing but stare forlornly at the object of his affection. Unable to tell her how he feels, his love is doomed to remain unrequited – it is never returned.

I ne’er was struck before that hour

With love so sudden and so sweet,

Her face it bloomed like a sweet flower

And stole my heart away complete.

My face turned pale as deadly pale,

My legs refused to walk away,

And when she looked, what could I ail?

My life and all seemed turned to clay.

And then my blood rushed to my face

And took my eyesight quite away,

The trees and bushes round the place

Seemed midnight at noonday.

I could not see a single thing,

Words from my eyes did start –

They spoke as chords do from the string,

And blood burnt round my heart.

Are flowers the winter’s choice?

Is love’s bed always snow?

She seemed to hear my silent voice,

Not love’s appeals to know.

I never saw so sweet a face

As that I stood before.

My heart has left its dwelling-place

And can return no more.

Over his professional life. Clare’s poetry was inspired by two great muses: nature and love. Poems, Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, was the collection that catapulted him into the public eye; all of the poems in this book beautify countryside scenes. His subsequent works were less widely read and he only really garnered huge appreciation a hundred years after he died. His later work became more and more serious, including one entitled The Dream which is actually a frightening description of a nightmare. In 1841 he was committed to Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, where (despite an incredible escape attempt in which he walked 80 miles home over four days eating nothing but wild grasses) he spent the last 18 years of his life.

Although he married Patty Turner (who was to give him 9 children over their life together) John Clare’s childhood sweetheart was called Mary Joyce. Unfortunately, his social station was far below hers, and he had no realistic hope of ever consummating his feelings for Mary. Over his life, he was to write verse dedicated to both women although, on balance, Mary was more often the subject of his love poetry. Here’s a quick snippet from another poem:

We’ll never be more parted

And changing as her love may be

My own shall never vary

Nor night nor day I’m never free

But sigh for abscent Mary

It’s hard to imagine what Patty would have felt if she ever read these lines; maybe that’s why she seemed never to have visited him in hospital! His love for Mary was to last his entire life: in fact, on learning of her death in 1838 (at the age of 41) he refused to believe the news. It’s easy to see aspects of his unrequited love for Mary Joyce in First Love, and also to find moments of disturbing intensity in what is otherwise quite a sweet poem.

Having said this, it’s important to remember when reading any poem that the speaker and the poet are rarely the same person. Poets, like writers, create characters (in poetry we call them speakers or personas) through which their thoughts are passed. Strictly speaking, the speaker in the poem is not exactly John Clare – he’s a representation of John Clare’s thoughts and feelings. Accordingly, I’ve never been absolutely sure that the poem actually does describe love at first sight:

I ne’er was struck before that hour

With love so sudden and so sweet,

Her face it bloomed like a sweet flower

And stole my heart away complete.

The diction here all points to a first seeing: struck, sudden, sweet. When her face blooms like a flower, figuratively this would mean it’s the first time her face has seen the light of day; more likely it’s simply the first time he has lain eyes on her. On the other hand, the simile would work equally well to suggest the way a person known for a long time can appear completely different under the influence of love. This would fit with Clare’s biography; he met Mary in 1803 when he was barely 10 years old. His feelings would surely have developed afterwards.

The intensity of emotion is partly created through the frequent hyperboles Clare employs to suggest the transformation of a person struck suddenly by feelings of strong love. I ne’er (never) was struck before this hour, stole my heart away complete, and even the repetitions of so and sweet play into this hyperbole. Further examples of hyperbole in the poem include: my life and all; seemed midnight (being the very middle of night); took my eyesight quite away (quite, in this context, means ‘very’); I could not see a single thing– there are many more for you to find. How you respond to this frequent hyperbole largely depends on what kind of reader you are: do you think it’s cute when someone falls so completely under love’s spell that all reason is thrown out of the window; or do you think he goes too far in his protestations of extreme love?

Considering this point will help you understand the literary context of the poem: letting yourself fall in love has long been depicted as a kind of tug-of-war between the forces of reason and emotion. In Greek mythology these oppositions were represented by the two sons of Zeus: Apollo and Dionysus. Apollo is the god of the sun, associated with order, reason, logic and clear-thinking. Dionysus is like your irresponsible younger brother: the god of (appropriately enough) wine who loves to drink, dance, carouse, who acts on instinct and is prone to being led by his emotions. These two figures have a long and illustrious literary rivalry; you’ll find their avatars in Wilde (The Importance of Being Earnest), Shakespeare (Twelfth Night; A Midsummer Night’s Dream), all the way up to Stephen King, to name just a few. In a way, the use of hyperbole always involves Dionysus getting one over on his clear-headed brother; the triumph of emotion over reason. Think of the kinds of things you say when you’re being at your most unreasonable: “this is the worst day ever,” “I wouldn’t talk to you if you were the last person left in the world,” and you’ll see what I mean.

Whether or not you think he’s exaggerating, Clare certainly feels the physical as well as emotional effects of first love, and he presents a series of images illustrating these effects on his body:

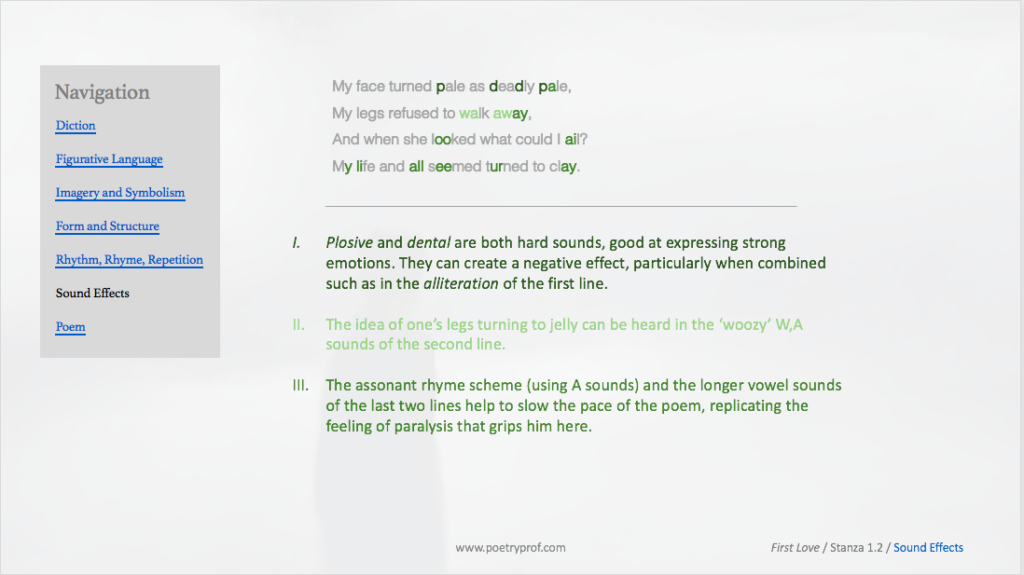

My face turned pale as deadly pale,

My legs refused to walk away,

And when she looked, what could I ail?

My life and all seemed turned to clay.

If you’ve ever felt this kind of hopeless infatuation, you might recognise these signs: your legs turn to jelly, your lips dry and stiffen, you don’t know where to look or what to say. Clare’s use of personification when he says my face turned pale and my legs refused to walk away illustrate how his body turns against him, disobeying his commands. The severity of his helplessness is compounded by the rhetorical question, what could I ail? cleverly using words from the lexical field of sickness (ail is the root of ‘ailment’; pale is associated with feeling unwell) as a substitute for ‘what could I do?’ The world seeming to stop still (my life and all seemed turned to clay) is an image straight from a romantic movie, when the lovelorn hero sees his intended for the first time in cheesy slow-motion. Again, hyperbole plays its part: My life and all and deadly pale both suggest this feeling is life-threatening!

Look at the first word of the second stanza – you might already have noticed Clare frequently breaking the old English-teacher rule that a sentence should not begin with and. In this poemand… and… nicely suggests the rush of thoughts and feelings that can overwhelm you when you are so suddenly hit with powerful love:

And then my blood rushed to my face

And took my eyesight quite away,

The trees and bushes round the place

Seemed midnight at noonday.

Compare these lines with the last few of stanza 1. Remember that freezing of the world when everything seemed mired in clay? The slowing sensation was reproduced through the sounds of the line: long assonant A sounds in all and clay, plus a long EE in seemed, slowed the pace of the poetry right down. Now you have a combination of sounds that speed everything back up again as the blood rushed to my face: the sibilant SH creates this sensation for us, as do quick dental and guttural sounds in blood, took, eyesight, and quite. What’s also interesting in these four lines is how modern the ideas seem. We often use the phrase ‘my world turned upside-down’ to describe the feeling when something new and wonderful suddenly drops into our lives. Clare gives us an image of trees and bushes round the place, with the speaker positioned in the middle, as if things are whirling dizzyingly round him. A simile completes the topsy-turvy sensation: seemed midnight at noonday speaks to the transformative power of emotion.

The modern, recognisable experience of Clare’s love crosses the years between his life and ours: we already discussed the way his body won’t obey him anymore, and his easy surrender of reason to emotion. Some people might think these count against the poem, though; the sentiments are a bit hackneyed and corny. I concede, love blooming like a sweet flower is hardly original. Actually, Clare’s reputation at the time of his writing was as a naïve and simple poet. People were prejudiced against his ‘earthy’ background. He grew up on a farm, and only sometimes attended day school. His parents were basically illiterate and much of his poetry praising nature is steadfastly pastoral. In defence of this poem against accusations of cliché, however, you can point out how Clare subverts expectation as often as not. Look at the way he employs pathetic fallacy, a literary technique by which the background (including the season, weather, geography and the like) mirrors human concerns. At a moment of great love, you might expect the sun to shine or the clouds to lift. By contrast, Clare’s poem turns dark: his speaker is blinded (I could not see a single thing) and noonday turns to midnight.

The poem intensifies in the second half of stanza two, in which an even more peculiar transformation takes place: words stream (start) from his eyes, not his mouth:

I could not see a single thing,

Words from my eyes did start –

They spoke as chords do from the string,

And blood burnt round my heart.

There’s a strange contradiction here: the ideas of being tongue-tied or serenading a loved one with a song are sweet, but Clare presents them with such intensity they become a little disturbing. Firstly, the speaker is not in control of his actions. Words come forth involuntarily, personified with their own agency. They spoke by themselves, without his participation. Secondly, the suggestion that love can bring pain as much as delight is strong in the final line: the image of blood burning is painful in itself, and the idea of blood burning around his heart suggests he is trapped in this helpless state. The feeling is further emphasised by plosive and guttural alliteration (underlined above), the combination of which can be very intense. Too, the whole scene is conducted in that unnatural darkness. I can’t help but think that the love portrayed in this poem is destructive to the speaker.

Perhaps this is because, just as in Clare’s real-life infatuation with Mary Joyce, the third stanza reveals that his love is not requited:

Are flowers the winter’s choice?

Is love’s bed always snow?

She seemed to hear my silent voice,

Not love’s appeals to know.

Read the two rhetorical questions with a heavy sigh. Then look carefully at what they say – Clare is implying that falling in love is beyond our control, and that we often find the conditions for love are completely unsuitable. He does this through oxymorons: flowers in winter, a bed of snow, silent voice are all words and ideas that shouldn’t sit alongside one another, just as Mary was an unsuitable match. The unsettling intensity of the words are at odds with the sing-song form of the poem: Clare unfailingly follows an ABAB, CDCD, EFEF rhyme scheme and the rhythm is a steady iambic pulse (de-dum, de-dum, de-dum) that, resembling a heartbeat, reminds us that love is associated with the heart.

Unusually for a love poem, the focus of the poem has not often been the object of his affection but the speaker himself. You can count how many ‘I’s and ‘my’s there are throughout: even at the end, when he briefly returns our attention to her sweet face, there’s three of them! By now, he’s totally feeling sorry for himself and so, fittingly, he ends with one last hyperbole:

I never saw so sweet a face

As that I stood before.

My heart has left its dwelling-place

And can return no more.

It’s almost as if the speaker blames the Mary-figure for not loving him back, despite his own inability to articulate his feelings. Most tellingly, he accused her of being a thief who stole my heart away. We discussed before how hyperbole indicates uncontrollable emotion; perhaps we should reconsider this when looking at the hyperboles in the final lines. Suppose he employs hyperbole purposefully. In saying I never saw so sweet a face might he be expressing cynicism that she is hiding her true colours behind an innocent mask? Is it a calculated ploy to win our sympathies by turning us against her?

Or maybe he’s just gutted that her Dad wouldn’t let them see each other. I’ll let you decide.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- I Hid My Love by John Clare

Another of Clare’s love poems, this piece explores what it’s like to be in love with someone who cannot return your affections. In many ways it is very similar to First Love.

- Sonnet 147 by William Shakespeare.

You may have thought Shakespeare’s love sonnets were all as nice as Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day… Well, you thought wrong! In Sonnet 147, he describes love as a ‘fever’ and the one he loves as ‘black as hell.’ It’s dark stuff.

- Love at First Sight by Wislawa Symborska

This brilliant poem, translated from Polish, considers the role of chance and fate in meeting your loved one.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying First Love at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to download our bespoke study bundle for this poem. Costing only £2, the study bundle includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on hyperbole in John Clare’s poem

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap activity or revision.

- 4 essay questions for you to practice with – and one complete essay plan for you to use.

And…discuss!

What do you think about John Clare’s depiction of First Love? Did it seem like love at first sight to you? Do you agree with the suggestion that he might blame her for not returning his unspoken affections? Why not share your ideas and opinions in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.