Put on your gloves and hat and come play in the snow with Robert Bridges.

“His words, often commonplace, are made unforgettable by some trick of speeding or slowing… or by some trick of simplicity…”

W.B. Yeats

Having lived in London during a winter of heavy snowfall, I immediately identified with this poem. One night, snow fell so heavily that all the trains were stuck, roads were iced over and traffic was jammed. I had to get to work in the north of the city. Several diverted buses, a comical-slippery walk and at least 3 hours late, my colleagues messaged me to tell me not to worry. So I gave up on work for the day, and meandered home through parks and down little streets, enjoying the winter spectacle of cars half buried, parked bicycles hidden, famous buildings transformed, trees bent double under the white weight of snow.

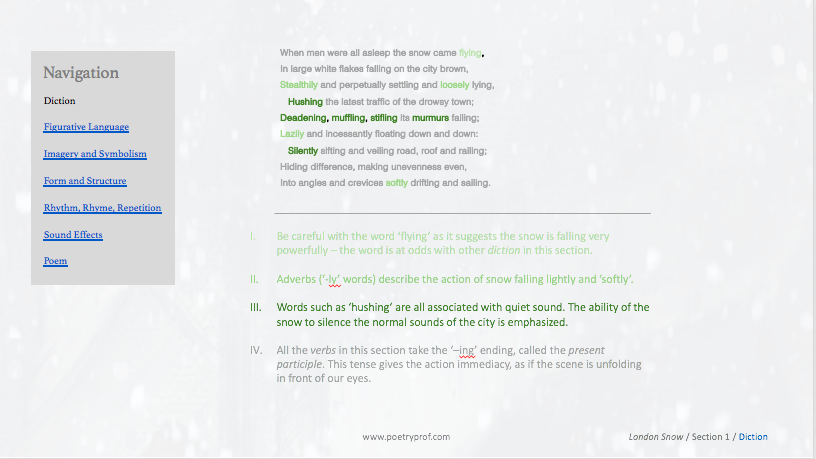

When men were all asleep the snow came flying,

In large white flakes falling on the city brown,

Stealthily and perpetually settling and loosely lying,

Hushing the latest traffic of the drowsy town;

Deadening, muffling, stifling its murmurs failing;

Lazily and incessantly floating down and down:

Silently sifting and veiling road, roof and railing;

Hiding difference, making unevenness even,

Into angles and crevices softly drifting and sailing.

All night it fell, and when full inches seven

It lay in the depth of its uncompacted lightness,

The clouds blew off from a high and frosty heaven;

And all woke earlier for the unaccustomed brightness

Of the winter dawning, the strange unheavenly glare:

The eye marvelled—marvelled at the dazzling whiteness;

The ear hearkened to the stillness of the solemn air;

No sound of wheel rumbling nor of foot falling,

And the busy morning cries came thin and spare.

Then boys I heard, as they went to school, calling,

They gathered up the crystal manna to freeze

Their tongues with tasting, their hands with snowballing;

Or rioted in a drift, plunging up to the knees;

Or peering up from under the white-mossed wonder,

‘O look at the trees!’ they cried, ‘O look at the trees!’

With lessened load a few carts creak and blunder,

Following along the white deserted way,

A country company long dispersed asunder:

When now already the sun, in pale display

Standing by Paul’s high dome, spread forth below

His sparkling beams, and awoke the stir of the day.

For now doors open, and war is waged with the snow;

And trains of sombre men, past tale of number,

Tread long brown paths, as toward their toil they go:

But even for them awhile no cares encumber

Their minds diverted; the daily word is unspoken,

The daily thoughts of labour and sorrow slumber

At the sight of the beauty that greets them, for the charm they have broken.

You can imagine how excited I was to discover London Snow: a poem which describes an identical scene to one I myself experienced, but from over a century before. Robert Bridges’ poem – a sensuous description of how overnight snow performs an astonishing, near-magical transformation on the city of London – could just as easily have been written in 1990 as 1890. Some lines described events exactly as I experienced them. The wonder I felt on opening my bedroom curtains onto the snowbound scene is expressed as: The eye marvelled – marvelled at the dazzling whiteness. I saw kids throwing snowballs, kicking through piled snow and tilting their heads back to catch snowflakes on their tongue: Bridges describes all this when he recounts schoolboys who “…freeze / Their tongues with tasting, their hands with snowballing / Or rioted in a drift, plunging up to the knees”.

This is a poem that rewards slow, leisurely reading (preferably out loud). It might be tempting to jump on the word flying in the first line and think that the snow fell in a sudden blizzard – be careful of this assumption. Look at the diction of the following lines: hushing, murmurs, lazily floating, silently sifting and veiling, drowsy. When the snow settles it lies in uncompacted lightness. The snowfall is persistent and impressive, but not violent. None of this language sounds urgent or dramatic at all; so read it slowly, unhurriedly, even ‘lazily’, like gently falling slow.

Robert Bridges was an English poet whose life and career spanned a good part of the Victorian period, including a long stint as Poet Laureate from 1913 until his death in 1930. He is one of a number of poets whose work can be seen to bridge the heavy formality associated with ‘classical’ English poetry and more modern 20thcentury forms. He enjoyed experimenting with poetic form, seeking to stretch some of the long-established rules of ‘traditional’ poetry. In particular he believed in syllabic meter: the length and rhythm of lines should be determined by syllable – not stress – count. True to his vision, London Snow contains many formal elements that are easy to recognise, but are employed in unusual ways, to recreate the impression of snow falling and gently carpeting the ground in a swathe of white. Take the opening few lines:

When men were all asleep the snow came flying,

In large white flakes falling on the city brown,

Stealthily and perpetually settling and loosely lying,

Hushing the latest traffic of the drowsy town;

In the third line alone there are a cluster of techniques which make you take that little bit longer reading to the end. Polysyllabic words (incessantly and perpetually have 4 syllables each); repeating the adverb ending ‘LY’ 3 times (plus a bonus LY in lying); linking his adverbs using and (the purposeful use of ‘and’ to connect items in a list is called polysyndeton). Look further down the poem and you’ll see there are no stanza breaks (the poem is written in continuous form); the lines are unbroken like a field of fresh snow. The sentences are long – if you’re looking for full stops you won’t find many; the first comes at the end of line 9, the next at line 18 and then, just when you think you’ve found a pattern, lines 24, 30 and 37. There are several examples of enjambment, such as: “And all woke earlier for the unaccustomed brightness / Of the winter dawning.” Enjambment encourages you to read from one line to the next without pause, mimicking the continuous, unceasing falling of snow.

Later in his career Bridges wrote a long poem in what he described as “loose alexandrines.” An alexandrine is a line of poetry containing six iambic feet (12 syllables arranged in de-dum pairs) and you can see Bridges experimenting with lines of similar length in London Snow. Read the four lines above and count the syllables for yourself. He’s definitely aiming for 11 or 12 of them in each line, although by his own admission Bridges was ‘loose’ about this, so the third line reaches 15 syllables. Whatever the exact count, the lines are longer and more stretched than you might be used to – an effective way to recreate the languorous feel of ‘persistent’, ‘incessant’ snowfall.

In a poem that is ostensibly about quietness and silence, there are a surprising number of aural elements. The rhyme scheme looks simple enough – alternate lines rhyme. Right? Check again – it’s not that easy! Bridges has adapted a form called terza rima, in which groups of three lines (tercets) follow the rhyme scheme: ABA, BCB, CDC and so on. In his version of the terza rima he has eliminated the stanza breaks (just like the fallen snow hides difference, makes unevenness even) It’s easy to see the pattern if you pair up the tercets into groups of six lines each. You should be able to see that the fifth line in each group predicts or ‘overlaps’ with the first line of the next group. Label the lines like this: ABABCB, CDCDED, EFEFGF, GHGHIH and so on (treat the odd 37th line as the first of a new, invisible group: ML M). Now: sew the groups back together; think about how snow resting on the ground has no visible breaks, how one section might ‘overlap’ into another, or how snow might blur the boundaries of what you think you can perceive; – you’re probably close to understanding how Bridges’ mind was working when he adopted the terza rima form for this poem.

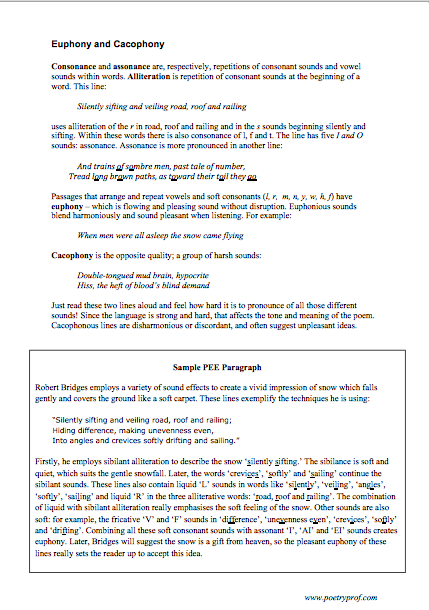

Terza rima takes care of sounds at the end of a line, but see how Bridges blends sounds within lines as well. There is occasional internal rhyme, for example, “Following along… a country company long….” All those ‘-ING’ and ‘-LY’ word endings so close together help with the blending effect, as does frequent alliteration: “Silently sifting and veiling road, roof and railing.” In fact, the poem makes liberal use of all the major alliteration types: alliteration, assonance, and consonance (alliteration of sounds anywhere in a word), so don’t overlook the F and L sounds in the line above. Where possible, Bridges avoids using hard consonant sounds. He prefers liquid, (L, R, W) nasal (N, M), and sibilant (S, Sh, Ch) alliteration, creating a poem in which soft sounds blend and overlap easily. The technical name for the use of softer sounds which blend harmoniously is euphony. The euphonic sounds suggests the tranquility of an unbroken blanket of snow and hints at the euphoric feelings of people awakening to a transformed city.

At its heart, this is what the poem is about: the transformative effect of snow on both the cityscape and the people of the city. And what a transformation! It doesn’t just look different – it sounds and feels different too. First, look closely at the diction in lines 4 to 7 used by Bridges to stress the quieting effect of the snow:

Hushing the latest traffic of the drowsy town;

Deadening, muffling, stifling its murmurs failing;

Lazily and incessantly floating down and down:

Silently sifting and veiling road, roof and railing;

His word-choice and phrasing suggest that the city is normally a loud and busy place, but today it has been ‘muffled’ or silenced. The usual sounds of wheel rumbling and foot falling are missing; other sounds are thin and spare.

Then notice how the snow also works to visually hide the city. Visual descriptions include veiling, hiding difference, unaccustomed brightness, unheavenly glare. The power of both visual and aural descriptions accumulates in the two lines:

The eye marvelled—marvelled at the dazzling whiteness

The ear hearkened to the stillness of the solemn air;

Dazzling is the city at its most white and still. Repetition of marvelled after a hyphen helps mark the peak of this crescendo, as does the reappearance of ‘white’ in whiteness, not seen since the first line.

After the transformative snowfall, the different, lighter atmosphere of the city can be sensed by watching labourers heading toward their toil. For a brief moment, the snow allows them to forget their daily thoughts of labour and sorrow. The word encumber suggests a weight has been lifted from their shoulders. The schoolboys show you even more vividly. Perhaps you’ve missed a day or two of school because of heavy snow? If so, you might be able to identify with their happiness! Look how quickly and eagerly they rush out to play in the snow: eight verbs in quick succession – calling, gathering, tasting, rioted, plunging, snowballing, peering, cried – emphasise the freedom they get to enjoy before they are once again confined by their daily classroom routines.

It’s clear that the changes wrought by the snow have a symbolic dimension: the snow contrasts strongly with the mundane, ordinary world inhabited by the people we see in the poem. The image of trains of sombre men, past tale of number trudging to work is biblical in scope, and presented in an odd, archaic register: it reminds me of the story of Exodus. Bridges’ father died in 1853, but his stepfather was a vicar and Bridges himself had once planned to enter the church. He later changed his mind and studied medicine at Oxford instead; but he never abandoned his religious beliefs. The snow is described as both heavenly and as crystal manna, a substance originating from heaven. ‘White’ is often symbolic of heavenly or religious purity, and St Paul’s Cathedral is referenced in the poem as Paul’s high dome. The snow – which derives from heaven – completely contrasts with the city, which is a mundane place, and the people in the city who are embroiled in everyday concerns. The snow is white; the city is brown. The snow is silent; people are loud. The snow is peaceful; people are boisterous. The opposition between ‘human and divine’ is made explicit when Bridges writes that war is waged with the snow. Rioting, describing the schoolboys kicking through a snowdrift, is a much stronger word than ‘playing’ or the like. That loud call of the boys is joyous – but it also ruins the silent scene: “O look at the trees!” they cried. “O look at the trees!”

At the end of the day, the transformative power of the snow is more than just visual and aural; it provides a relief from suffering, a pleasant diversion (their minds diverted) and a reminder of the divine in a world that doesn’t seem very godly. But the respite is short-lived. It’s here for today, but it will surely melt away and soon the ordinary state of things will return. In fact, this process begins even before the end of London Snow – look how the colour of the city emerges from the snow as the men march in long brown paths. The last line of the poem, for the charm they have broken, suggests that people’s true nature, and the normality of the city, will be reasserted before long.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Snow in the Suburbs by Thomas Hardy

Any poem that gets away with rhyming Every branch big with it and Bent every twig with it has my full appreciation. You’ll see the ideas deployed in Frost’s poem – personification; transformation – used by Hardy too in this little bite-sized poem.

- Snow by Mao Zedong

Yes, that Mao Zedong. Everyone knows the Chinese Chairman from his controversial cultural and social policies. Few realise that he was also an extremely accomplished poet. He adopted a formal style, aping the classical greats, but often wrote about topics personal to himself or of concern to his country. This poem is inspired by winter in the mountainous regions of his home county, Hunan.

- Poor Poll by Robert Bridges

The first, and some say the best, of his poems written in his ‘new meter’ whereby the number of stressed syllables in a line was extended to six rather than the usual five.

- The Snow-Storm by Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Announced by all the trumpets of the sky” arrives the snow in this poem by Emerson, who often wrote poems inspired by the natural world. This one, about a traveller caught in a snow storm and forced to seek refuge in a farm house, is one of his most famous.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying London Snow at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of the poem’s poetic and technical features.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on how Robert Bridges creates effects using different kinds of alliteration.

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap activity or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What do you think of this reading of Bridges poem? Did you read any meaning into the symbolism of the snow? Did the poem touch a chord with you too? Let others know what you think by leaving a comment below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.