Don’t look back in anger, advises Thomas Hardy; but is he hiding deeper regrets?

“Whatever it was that makes for his strange greatness is hard to describe.”

Irving Howe, literary critic,1920 – 1993

Imagine you are getting pretty old, well into your eighties, say, and feel like you’re reaching the last days of your life. What do you think you might do with the time you have left? If you’re Thomas Hardy, the answer is to pen a last poem, one that would not be published until after his death less than a year later. Written from the point of view of somebody who considers their own life to be unremarkable, He Never Expected Much is a sad paean to mundanity and mediocrity. The speaker reflects back on a life of boredom and even discomfort, yet seems content nevertheless. When he was but a small boy, he was constantly told not to expect too much and be modest in his ideas about life. Looking back from his older and supposedly wiser vantage point, he expresses contentment in his choice to live life with a pessimistic outlook. However, to some readers, this may come across as something of a self-defeating attitude and the poem obliquely encourages us to criticise the speaker’s unwillingness to rock life’s boat just a little bit. By the end, we find ourselves asking if it’s possible to be truly happy if we curb our ambitions and accept whatever comes, no matter how limiting our circumstances might be. Or should we fight against mediocrity and try to blaze our own trails through life instead?

Well, World, you have kept faith with me,

Kept faith with me;

Upon the whole you have proved to be

Much as you said you were.

Since as a child I used to lie

Upon the leaze and watch the sky,

Never, I own, expected I

That life would be all fair.

‘Twas then you said, and since have said,

Times since have said,

In that mysterious voice you shed

From clouds and hills around:

‘Many have loved me desperately,

Many with smooth serenity,

While some have shown contempt of me

Till they dropped underground.

‘I do not presume overmuch,

Child; overmuch;

Just neutral-tinted haps and such,’

You said to minds like mine.

Wise warning for your credit’s sake!

Which I for one failed not to take,

And hence could stem such strain and ache

As each year might assign.

They say that just before you die, your whole life flashes before your eyes. Well, in this poem, life doesn’t so much flash past as slowly stutter, like a man flicking through the scrapbook of his life and finding most of the pages are blank. There’s not much to say or comment on except for the fact that life was not fair and that the living of life is both painful (ache) and not really worth the effort (strain). Any highlights – relationships, children, achievements, friendships, happy memories – are missing. The feeling one gets is that the speaker’s life was more grey than colourful, an image created in the third verse by the phrase neutral-tinted. Hardy was fond of the word neutral; he used it elsewhere in his work, most notably as the title of a poem called Neutral Tones in which he laments a failing romance. Here too, the word neutral creates a weak, washed-out impression of life; okay, things might not be bad, but they aren’t good either. It’s a rueful word that suggests the speaker’s life was, on reflection, only mediocre – and his attempts to dress this up as a win are not entirely convincing.

The poem is written as a monologue spoken by a man of advancing age (Hardy was eighty-six when he wrote this) to an audience of, well – the World itself, which is personified as a figure who can be addressed directly in a slightly curmudgeonly way. A poem’s conceit is any central idea, often metaphorical, that is used to convey the writer’s theme. In He Never Expected Much, Hardy’s conceit is that, because the World predicted him so little, he cannot be disappointed with his life because it turned out exactly as promised (Never, I own, expected I). As a young boy he was warned not to set his sights too high and that he should simply accept his limited lot in life: do not presume overmuch, child. In the face of such frank advice, we are subtly being given a choice about how to live: should we be realistic and accept that true happiness is not possible, settling for mere contentment or satisfaction? Or should we be idealistic and strive for better? Hardy has his speaker come down firmly on the realistic side of this debate. Having been promised scraps, he forces himself to be content, not fighting to improve his lot in any meaningful way. The last line of the poem reveals his mindset that bad things are unavoidable and decided by fate, as each year might assign. For this reason, he’s proud that he’s heeded the wise warnings of the world and not been too ambitious for anything more.

In the words of Queen Gertrude, though, ‘The Lady doth protest too much, methinks.’ Hardy was no lady, but I get the feeling that maybe he’s pulling the wool over our eyes just a little. While he professes satisfaction, his tone of voice suggests the opposite. Tone is an aspect of poetry that can be hard to pin down, especially here where it seems to work ironically in opposition to the words he actually says. For example, when he states he failed not to take the World’s advice he seems to be smugly asserting that he ‘got it right’. But his choice of words, such as failed and not, express only negativity. Elsewhere he seems wistful and even lonely, like when he’s thinking back to himself as a young boy and the world seemed so wide open and enticing (more on that later). Also, the way he keeps inserting little qualifiers into things hardly screams satisfaction: well… upon the whole… I own… much as… and such… for one… are the best examples of little words and phrases that modify each sentence in way that’s vague and non-commital, as if the speaker is not quite being honest and clear about the things he’s saying. At best his tone could be described as ‘resigned’; at worst, I think his stoic words cover up deep regrets. He doesn’t sound satisfied at all, he sounds downright sad. Hardy’s skilful poetry creates an all-pervading melancholia as if, in the final equation, his speaker regrets being so passive. Most obviously, he employs repetitions at the beginning of each stanza; for example, you have kept faith with me, kept faith with me. Each time he repeats a phrase, he’s expressing ennui in the repetitive grind of a life endured rather than enjoyed.

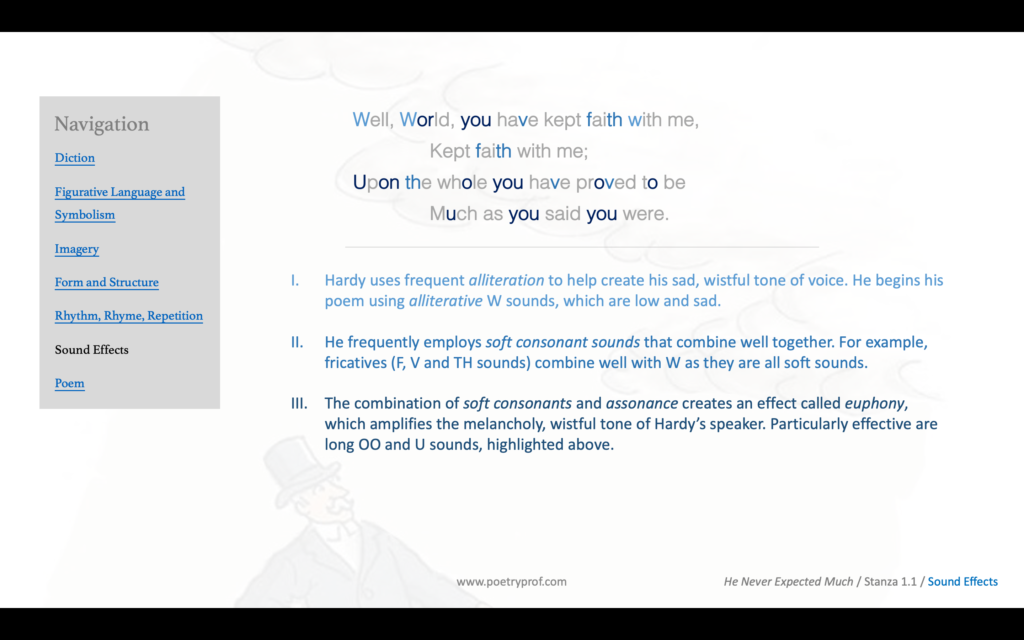

Repetition works in combination with sophisticated patterns of sound to further undermine the speaker’s purported stoicism. While there are all sorts of categories of alliteration, most consonant sounds can be defined straightforwardly as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft.’ Hard sounds are made with letters like D, T, B, P, G, K, X and tend to create active effects such as impacts, noise, clatter and so on. Soft, more mellifluous sounds are made by consonants such as F, H, L, M, N, R, S, V and W. They are much better at creating understated emotional effects like sadness and melancholy. Knowing this, it should be no surprise to see the majority of sounds in this poem are created using softer alliterations, such as the W sound which kicks off the very first line: Well, World… Other soft consonant sounds include fricatives made with F, V and TH (have, faith, with, proved) and sibilance made with S, SH, C and CH. Just check out the number of sibilant sounds in lines such as: much as you said you were since as a child I used to lie or many with smooth serenity, while some have shown contempt. The sounds of the poem work against the meaning of the words to suggest that, as the moment of reckoning nears, the speaker might regret the path he fatalistically chose to take. Nowhere do the sounds of the poem conspire to create irony more than when Hardy tells us he thinks the World’s promises of mediocrity were a wise warning. Not only does he use that unmistakeable W alliteration again, but he also marks this line with an exclamation mark. For me, the line is too emphatic. Is he trying to convince us… or persuade himself?

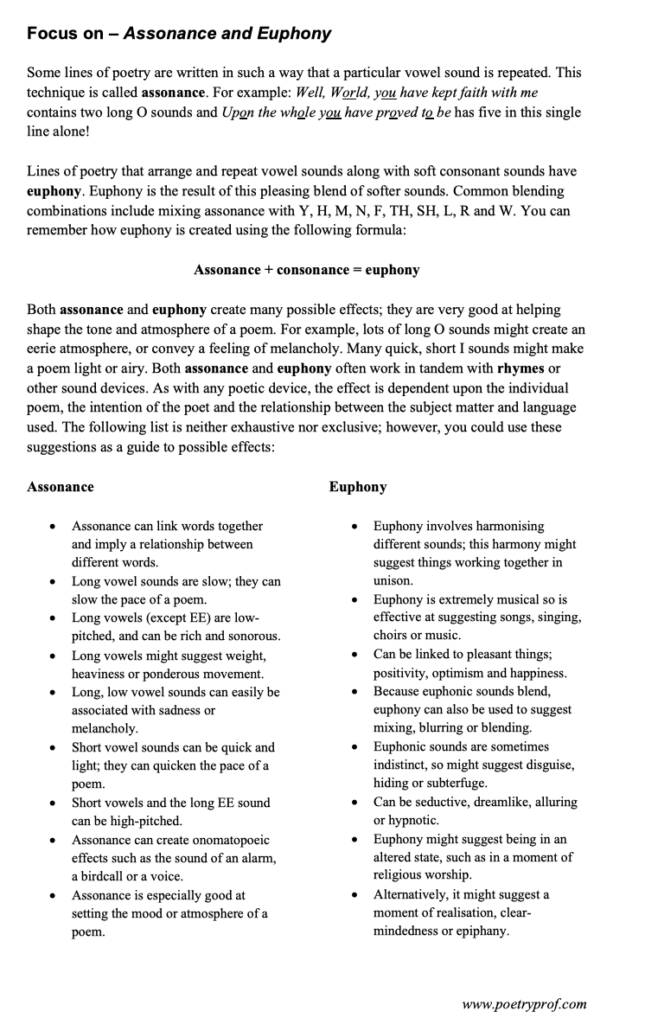

As a master of his craft working on one of his final poems (he’s an octogenarian at this point, remember) Hardy isn’t content giving us run-of-the-mill alliteration. Instead, he absolutely soaks his poem in melancholy sounds, leaving any astute reader in no doubt that, while he might say he’s content at hitting the low ceiling of life’s expectations, he’s far from truly happy. Assonance (the repetition of vowel sounds) works in combination with all those softer consonant sounds to create an effect called euphony which is a subtle but very powerful way of evoking sad feelings. Let’s focus on just one of these sounds, the repeated use of long O, as a case in point. Long O picks up and amplifies low, mournful sounds like the elegiac humming of a baritone choir. You’ll find the combination of O with other soft letters in stanza one words like world, you, upon, whole, you, proved, you, you, used, upon, own and would. Words with similar sounds in the second stanza are: you, you, clouds, loved, and, in particular, around, smooth, some, shown, contempt and underground. Combining assonant O with M or N creates a low, bass euphony that is most mournful. The letters N and M are created by trapping air inside the nose (hence the technical name nasal) simulating the way we bottle up negative emotions, so they work brilliantly throughout He Never Expected Much. Examine verse three and see if you can find examples of nasal (or other soft consonant) sounds being used in combination with assonance (creating euphony) for yourself.

A dimension of the poem that I really enjoy is that, underneath all the melancholia, Hardy gives us the niggling impression that life didn’t have to be this way at all. Despite meagre promises, there is enough imagery in the poem to suggest that opportunities for joy and self-actualisation actually do exist – if we have the wherewithal to go out and find them. The poem’s strongest and most impactful symbol is of neither sadness nor satisfaction, but of the possibilities that are out there waiting to be discovered: as a child I used to lie upon the leaze and watch the sky. An open sky is as clear a symbol of boundless opportunity as you’re ever likely to get. Is the poem implying that in his youth the speaker was something of a dreamer? In that case, why did he allow the World’s vague understatements to dull his ambition? One might argue that the sky is always going to be out of reach for mere mortals, which is a fair point, and it’s ambiguities like this that are up for discussion. Here’s another philosophical conundrum the poem throws up: if the boy had not been promised a mediocre life, would he have eventually lived one anyway? Or is it only through thinking he knows the future that he brings that future into existence? After all, he was subject to constant reminders that his life wouldn’t amount to very much: ‘Twas then you said, and since have said, times since have said… and the difficulties of the world do build up to seem quite overwhelming by the end (look how stem such strain employs alliteration again to really pile on the pain). However, I feel like the boy has let the World determine his future for him too readily and he certainly comes across as a very passive person, particularly when the verbs lie and watch are taken into account. In today’s psychological parlance we might define the speaker as having a fixed mindset, and I wonder if things might have turned out differently for him if he was less fatalistic and saw the World’s promises as a challenge to be surmounted instead of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Stanza two thickens the philosophical mix by adding clouds and hills into the scene. If one is of a naturally pessimistic bent, these features might be seen as trapping, enclosing, or limiting the boy in some way, just as hills might shorten one’s view and clouds can block the sun (notice how they are described as wrapping around the speaker’s position). But, if one is inclined to view things more positively, clouds and hills might be hiding wonders that are just a stone’s throw away. At this point, the speaker admits that the voice he hears sounds mysterious, a word that absolutely rebuts the idea of the World being an inherently limiting and not-fair place. If one has a get-up-and-go attitude, mysterious simply sweetens the deal with the promise of adventure – there are discoveries to be made and secrets to uncover! Perhaps the problem is the boy’s position is just too comfortable. After all, the word leaze is an archaic reference to a patch of open ground, such as a meadow or grassy pasture, suggestive of warmth, comfort and ease. The word derives from the root ‘lea’ which survives across England’s rural West Country, where Hardy spent much of his life, in place names such as Lea Barton, Lea Copse and so on. The poem presents the possibility that the boy didn’t have the motivation to get up from his comfy repose, get out there, and forge his own fate.

Hidden in plain sight, alternative approaches to life are strongly implied in stanza two. In an extended passage of direct reported speech, the speaker mimics the words he remembers the World speaking to him so grandiosely: many have loved me desperately, many with smooth serenity, while some have shown contempt… Again, it feels like the boy has only heard half the message and predestined himself a future that was never fixed. These lines reveal outright that there’s more than one way to live life; desperation, serenity, and contempt are wildly contrasting ways to respond to the world’s challenges. Stanza two ends with a reminder that, no matter how we go about the business of living, death waits for us all (dropping underground) and the world will go on regardless. Given this inescapable fact, doesn’t that mean we should try to live life the way we want to rather than the way we are told to live it? This line actually destroys the euphony that Hardy’s been so assiduously creating, instead giving us a cacophony of hard consonants (D, P, G) in a sudden burst. The effect is jarring: the mask of smug satisfaction slips and something angry, bitter and raw – perhaps something more genuine – is bared for just a brief moment.

Therefore, while He Never Expected Much purports to be a poem about dying, it’s really much more a poem about living. It reminds us all to embrace opportunities that come our way because one day it will be too late to go back and make amends for chances missed. The poem is written in a simple sing-song form (whether the lines are two, three or four beats long, a steady iambic rhythm metronomically marks time for us) and even rhymes pleasantly, lulling us into passively accepting a melancholy, mediocre life when there’s so much more that we might strive for. Through simple irony (the speaker says things that he doesn’t necessarily believe himself) Hardy encourages us all to ponder some weighty philosophical questions: are the patterns of our lives fixed for us by circumstance, should we not presume overmuch? Or should we strain every sinew to live lives of enjoyment and self-fulfilment, whatever we might be told?

Sadly, we are left with the nagging impression that Hardy’s speaker has gotten it all wrong.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Neutral Tones by Thomas Hardy

He wrote this poem when he was much, much younger – but Hardy views the world through the same grey-tinted glasses. Was he just a bit of a pessimist all along?

- Waterfall by Lauris Edmonds

Almost the polar opposite of Hardy’s lament, Edmonds metaphorically views life as an arcing, glittering waterfall and, even though she’s close to striking the bottom, she doesn’t regret a moment of her life.

- Fatalism by Gianfranco Aurilio

Not everybody lets themselves be limited by circumstance. In this short and highly memorable poem, translated from Italian, Aurilio says that he’s tired of fording rivers and never getting to the other side – but he carries on anyway because that’s what life is all about.

- One Art by Elizabeth Bishop

If you want a masterful demonstration of the effects of irony, look no further than Elizabeth Bishop’s famous poem. The more she tells you ‘the art of losing isn’t too hard to master’, the less you believe her.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying He Never Expected Much at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how assonance and euphony are created in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Thomas Hardy’s poem? Do you agree that the poem is ironic and the speaker is not being entirely honest with us or himself? Is realism or idealism better in this situation? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

thanks you it’s really helped me