Thom Gunn gives form to fear in a time of crisis.

“When he wrote about the AIDS epidemic and the death of friends, Gunn… made art out of loss.”

Edmund White, writing on Gunn’s death in 2004.

Thom Gunn was a British poet, born in Kent and educated at Cambridge, who moved to America to live with his partner Michael Kitay. He would live in California for the rest of his life, studying poetry and eventually teaching in two stints at Berkley University between 1958 and 2000. While in the US, Thom would live through the AIDS pandemic of the 1980s, a decade during which HIV and AIDS went from being virtually unknown to, by the mid-eighties, the most-feared disease on the planet, infecting150000 new victims each year. Little was known about either HIV or AIDS when these conditions emerged, and it was referred to as a ‘gay disease’ because gay men were one of the groups commonly affected. Thom was personally impacted by the disease through the death of many of his gay friends. He spoke and wrote about ‘the plague that cut them off so early’ and his published book of poetry, The Man with Night Sweats, from which this is the title poem, was in part a tribute to his fallen friends, as well as a way of personally coming to terms with the constant threat of infection and death. On top of this, the collection, written by a gay man and insider voice, would become an important way of engaging with wider society. People were afraid and, unfortunately, persecuted and marginalised the gay community who they believed was responsible for the spread of the virus:

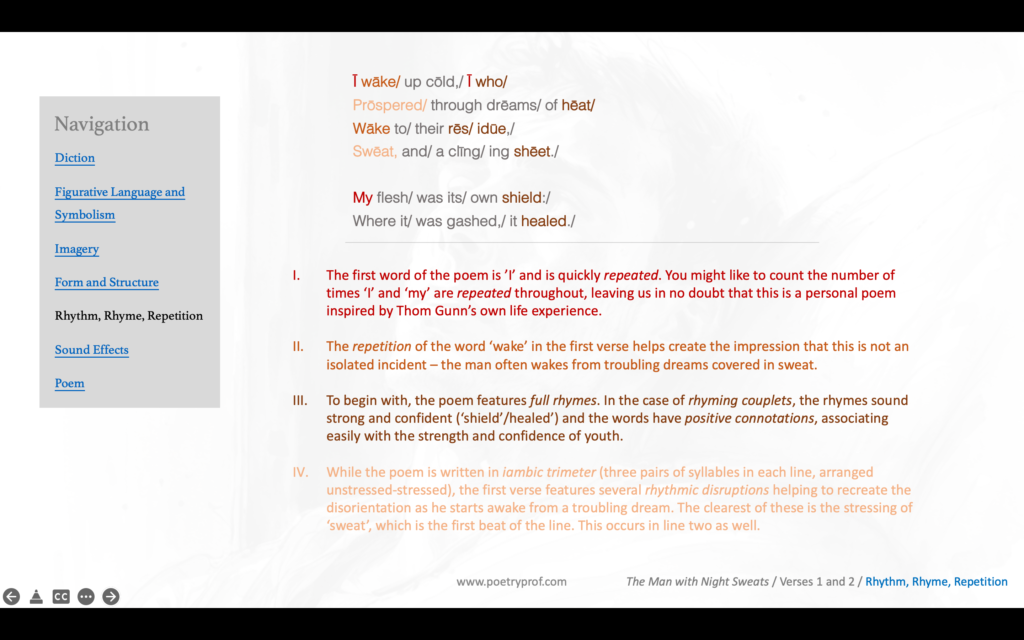

I wake up cold, I who Prospered through dreams of heat Wake to their residue, Sweat, and a clinging sheet. My flesh was its own shield: Where it was gashed, it healed. I grew as I explored The body I could never trust Even while I adored The risk that made robust. A world of wonders in Each challenge to the skin. I cannot but be sorry The given shield was cracked My mind reduced to hurry, My flesh reduced and wrecked. I have to change the bed, But catch myself instead. Stopped upright where I am Hugging my body to me As if to shield it from The pains that will go through me. As if hands were enough To hold an avalanche off.

Somewhat contrarily though, now that you’ve read the poem, I’m going to recommend that you don’t think about it solely as an ‘AIDS poem’. After all, words like ‘illness’, ‘disease’, or ‘AIDS’ never appear and the poem explores the way a sudden recognition of one’s own mortality can have dramatic psychological effects, regardless of context. In common with many young people, Thom lived his life fearlessly, with less inhibition than older folk with a little bit of experience under their belts – and why not? After all, when one is in the full vigour of health thoughts of ageing, illness, and death seem very far away. But as people get older and discover more about the world’s dangers, they tend to be more cautious, and regret reckless behaviour that might have had serious consequences. Written after realising he became sexually active in a world where AIDS was rampaging through young, otherwise-healthy young men, this poem reveals that no matter how invincible we may sometimes feel, we are helpless in the face of dangers that are too just big to avoid. Therefore, while the collected poems in The Man with Night Sweats are a response to the AIDS pandemic, in isolation I would argue that this poem’s central thematic concern is more simply the frightening realization of one’s own mortality.

To explore this idea Thom presents contrasting images of himself as a fearless young man compared with how he feels in the present day, after he has suffered a profound psychic reversal. You’ll probably not need me to point out that the first few verses switch from the present tense to the past tense and back again, a way of elegantly conveying ideas about the same person at two different stages of life. In the first two lines, the difference between his younger and older-self is expressed through the contrast between cold and heat. In the present day, older-Thom wakes up cold. Dig a little deeper into this word: negative connotations include fear (we shiver with fear, for example) and perhaps loneliness (one can be ‘left out in the cold’) an idea that surfaces later in the poem. The word residue is also an important link between the past and present. On one hand it directly refers to the residue of his sweat soaking into his bed sheet; on the other hand, residue means ‘traces of something left behind,’ much as his present-day self contains the regret-soaked memories of his past. Waking up suddenly, covered in sweat, heart beating fast, and tangled up in a bedsheet is something that most people have experienced at least once in their lives, so we should understand sweat as the central symbol of a chilling, mortal fear that paralyses one in the prime of life.

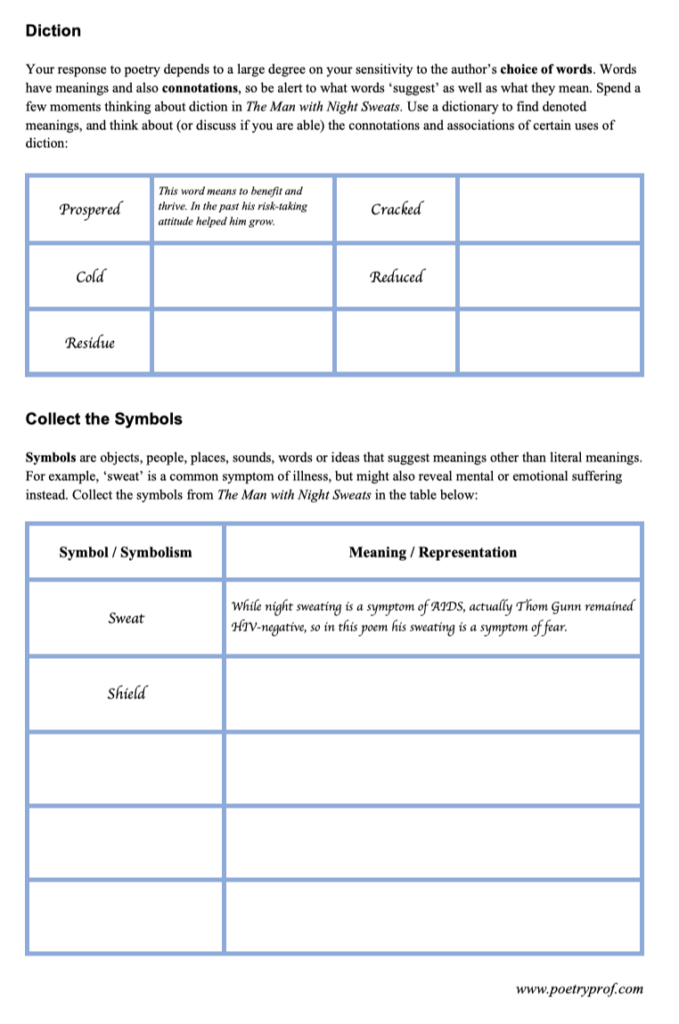

The fearless, uninhibited way he used to embrace life’s challenges can be seen through other examples of diction; when he writes about his younger self, he tends to use positive diction such as prospered, meaning he felt like his ‘get up and go’ attitude to life was successful. The poem reveals his sexual journey of discovery without ever being explicit. The phrase I grew as I explored the body and the word adored suggest coming into his own sexual identity. Heat connotes passion, and a world of wonders describes a time when Thom was filled with confidence and curiosity. He used to be robust (strong), fearless and ignorant of dangerous consequences – in fact, when he says risk that made robust he admits that he lived life according to the maxim ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’. Poetically, the confidence of youth is evoked through one or two regular sound patterns, most noticeably full rhymes such as who/residue, heat/sheet, and shield/healed, arranged in a strong and certain ABAB AA pattern. Complimenting the rhyme scheme is alliteration: a world of wonders and the risk that made robust use this technique to strengthen the feeling of self-assuredness Thom had in his own strength and infallibility.

Now, though, Thom has changed his outlook. He regrets his flagrant disregard for danger, directly using the word sorry in verse five. After all, several of his friends died during the AIDS pandemic and he has come to fear death, which he feels is shadowing him closely. It’s clear that where his younger self was fearless, he now lives in constant anxiety. Look at some of the words and images presented in the present tense to feel fear and desperation pulsing under the surface. Clinging, for example, has the connotation of hanging on desperately; is his clinging sheet protecting him or is it stifling him like a shroud? Of course, sweat is the defining symbolism of the poem; while night sweats are a symptom of AIDS, Thom himself remained HIV-negative, so this is not necessarily an image of infection. Rather, Thom’s poem reveals a young person who suddenly realises he has been exposed in some way to the danger of infection. Given the number of times he uses the word I and my (I is the first word of the poem) it’s likely that Thom is using the personal voice. However, we should be mindful that the speaker of a poem is not always the poet himself; in this case, in an act of solidarity with those stricken by AIDS, Thom may be using the invented voice of a young man who has received a positive diagnosis.

His overwhelming fear derives from the understanding that his body, rather than being indestructible, was, all along, fragile and vulnerable to harm. His naïve belief in his own youthful infallibility has been stripped away by the reality of disease in the world around him. In his younger days, he metaphorically thought of his body as a shield, protecting his inner self from harm. Given this is not a long poem, it’s surprising how many different words he uses for his own body: shield, skin, flesh, hands and body itself all feature in the poem. A shield is tough and impenetrable, where skin and flesh are soft and easily damaged. As a young man, Thom felt like Wolverine, able to recover from any injury: where it was gashed, it healed. Now, however, Thom fears that his body is irreparably weakened, as AIDS weakens the immune system, making the body more vulnerable to other illnesses. He says: the given shield was cracked… my flesh reduced and wrecked. The more his fear overcomes him, the more Thom disrupts the established patterns of his poetry, forming the impression that something is wrong with his adult self. These disruptions are especially pronounced in verse five. While the poem rhymes regularly, notice that verse five subtly changes the quality of rhyming words, using half-rhymes instead of the full-rhymes we have come to expect: sorry/worry and cracked/wrecked. Also called slant-rhymes, half-rhymes are created when either the consonant or the vowel sound is the same – but not both. In the words cracked/wrecked, for example, the consonant sound (CK) rhymes, but the vowel sounds (A and E) do not. Where full-rhymes could be said to characterise the confidence and fearlessness of youth, half-rhymes sound less assured and not at all confident. He does the same with rhythm and meter. The poem largely unfolds in lines of iambic trimeter, where each line features three pairs of syllables arranged in an unstressed-stressed pattern. The most obvious variation occurs in the two lines ending sorry and hurry where he employs a technique called catalexis to extend each line by a single, unstressed syllable. Here’s what verse five looks like with stressed beats marked and extra syllables bracketed:

I cān/ not būt/ be sōrr/ (y) The gīv/ en shīeld/ was crācked/ My mīnd/ redūced/ to hūrr/ (y) My flēsh/ redūced/ and wrēcked./

Whereas up until now every line ended on a stressed beat (called rising rhyme), you can see these two lines ending on a weaker, less assured note called falling rhyme. Moreover, the poem begins to employ harder, more painful alliterative sounds, such as plosive B in I cannot but be sorry, and a series of strong gutturals (hard G, C and CK sounds) in the words cannot, given, cracked and wrecked. One of the poem’s most subtle effects is the depiction of emotional fear in physical concrete images: sweat-soaked sheets, a cracked shield, gashes and lesions on the skin. The formal elements of verse five blend well with the tactile images to evoke the fear of bodily harm that is undermining Thom’s confidence so profoundly.

Having established his overwhelming fear, the final three verses explore the effect of fear on Thom’s present and future self. The poem links our psychological strength with our physical strength very effectively, asking how much a healthy mind depends upon a healthy body. In verse five, this relationship is strongly implied through the juxtaposition of two lines with identical grammatical structures, creating a parallelism: My mind reduced to hurry, My flesh reduced and wrecked. While his flesh, his shield, is a physical object, its weakening affects his mind before his body begins to exhibit any symptoms. Where before he was an active participant in the world, now he seems incapable of completing simple tasks, such as dealing with his sweat-stained bedsheets: I have to change the bed, but catch myself instead. Fear has paralysed him. The seventh verse presents an extended image of himself frozen in time (stopped upright), ramrod straight, hugging my body to me as if to shield it. It’s not really his body that is failing, but his mind, his confidence and that feeling of infallibility. He’s become acutely aware of his own fragility, consumed by thoughts of the pains that will go through me. In another subtle change, this line employs future tense (will) for the first time; will is an example of a modal verb whose job is to express degrees of probability. A very strong-and-certain word, will expresses the certainty (less certain modals are ‘may,’ ‘might’ or ‘could’) of pain in his near future – whether physical, psychological or both. While Thom was to remain HIV-negative, he could not have known this at the time he was writing. Contracting HIV would result in considerable physical pain, and that’s on top of psychic trauma and the emotional pain of losing one’s closest friends to the virus. Consider how the phrase hugging my body to me implies that he is completely alone, as if his friends have already gone. In a wider sense, this also reminds us of how the gay community were abandoned by wider society during this time of need.

Thom ends the poem with an image of helplessness in the face of destructive forces that are simply too large to avoid and too strong to resist. The final line features an onrushing avalanche that stands in as a metaphor for the oncoming AIDS pandemic. Thom stands in front of the avalanche with only his hands to shield him, resigned to the knowledge that they are not, and have never been, enough to hold back the onrushing storm. Not only is the image pitiable, but his tone of voice is leaden and resigned, as if he’s had all the fight beaten out of him by the knowledge he’s acquired. Once again, sound plays a huge part in conveying the emotion of the scene. Where the second half of the poem has employed mostly half-rhymes, the final couplet returns to using full rhyme (enough/off), giving the end of the poem a sense of certainty and inevitability: the avalanche is coming and there’s no way to protect oneself. And Thom subtly alters his patterns of alliteration and consonance (alliteration repeats letters at the beginning of words; consonance repeats letters anywhere in the words) too, dropping most of the gutturals that accompanied his images of pain and employing a mix of aspirant and fricative sounds instead. Made with the letters H, V, F and GH, these sounds suggest the avalanche is rumbling closer, and also transmit the strong emotions of the speaker, as his breath is either exhaled or forced out of the mouth. You can find aspirant in the words hands and hold and fricatives in the words avalanche, if, enough and off.

In other literary genres, particularly tragedies on stage, anagnorisis describes the moment a hero realises the truth about himself, the people around him, or the world in which he lives. Tragedy happens when this moment of realisation arrives too late: thankfully, this was not the case for Thom – but it was for many of his friends. So his poem encourages us to consider how we might act in a world that contains lurking dangers, not always visible, but around us nevertheless.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Lament by Thom Gunn

Written after being with a friend in hospital as he died of AIDS, this poem is about how to cope and come to terms with the heartbreaking grief of this daily reality.

- Howl by Allen Ginsberg

One of the defining protest poems of an era, Ginsberg’s poem is, quite literally, a howl of anger and grief at the injustices of the Beat generation. Dedicated to Carl Solomon, a friend who was placed in a mental asylum.

- Hospital Writing Workshop by Rafael Campo

If you read literature to try to see the world through the eyes of others, you’ll love this poem by a writer who sees writing as a tool for empathy and healing. Set in a hospital ward for chronic and critical patients, the speaker reflects on a writing workshop he just gave, and what it means for the patients – and for himself.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying The Man with Night Sweats at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining how Thom used rhyme in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Thom Gunn’s poem? What was your take on the fear that seems so overwhelming in the poem? How did you interpret the avalanche at the end? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.