If you think that getting married means living happily-ever-after, Dennis Scott will probably want to have a word.

“…one so steeped in various art forms, whose life and work were of such great impact and importance…”

Yashika Graham, Poetry Society of Jamaica

How many stories have you read, or films have you seen, that end with the joyful union of two people in holy matrimony? The hero and heroine ride off into the sunset; the girl gets the boy she’s been chasing; the prince and princess get married and go to live in their fairy-tale castle. All ends ‘happily ever after.’ Well, not quite, Dennis Scott would say. The author of today’s poem, Scott takes that traditional story ending as his starting point and suggests that marriage is not the end, but the beginning of a journey. And it’s not an easy journey either. In this poem, roads disappear, maps are never true and wilderness appears out of nowhere:

He never learned her, quite. Year after year

that territory, without seasons, shifted

under his eye. An hour he could be lost

[blur]

in the walled anger of her quarried hurt

on turning, see cool water laughing where

the day before there were stones in her voice.

He charted. She made wilderness again.

Roads disappeared. The map was never true.

[/blur]

To read the poem in full, please click here

[blur]

Wind brought him rain sometimes, tasting of sea -

and suddenly she would change the shape of shores

faultlessly calm. All, all was each day new;

the shadows of her love shortened or grew

like trees seen from an unexpected hill,

new country at each jaunty helpless journey.

[/blur]

So he accepted that geography, constantly strange.

Wondered. Stayed home increasingly to find

his way among the landscapes of her mind.

Dennis Scott is a Jamaican poet, playwright, actor and director who made his name after Jamaica achieved independence in 1962. His first collection of poetry made distinctive use of ‘nation language,’ a Jamaican vernacular tainted with negative connotations; a vulgar patois, a slave lingo, a dialect. Scott, and other writers such as Kamau Braithwaite, wanted to elevate this form of English and give it the status it deserved in literature. Nation language is a creole (a form of English heavily influenced by African languages) more akin to the tongues spoken by slaves and labourers brought to the Caribbean.

These concerns are not, you would think, central to Marrysong, although the poem does feature a kind of struggle for independence played out between the two personas (stories have characters; poems have personas) – one man, one woman – who form its central relationship. It is, though, about identity; particularly how marriage places pressure on a person’s core identity. There are no ‘and they lived happily ever after’ platitudes here. The poem is honest about the challenges of marriage; the mistakes one might make when trying to draw close to another; the way one’s privacy may be eroded by living intimately with someone else; the clashes that inevitably result when two people agree to love and live together, but disagree as to how that relationship should actually work.

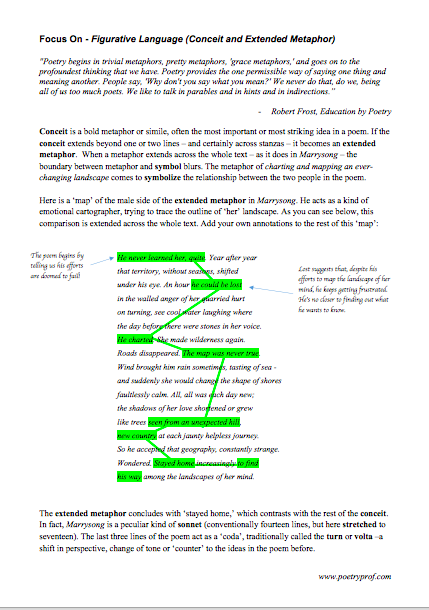

Scott frames the marriage using an extended metaphor (a type of metaphor that extends across a text) of ‘journeying and exploration.’ There are two aspects to this metaphor: on one hand we have ‘her’, depicted as an unexplored terrain, a territory. ‘She’ takes on aspects of this landscape; quarried, cool water, stones, wilderness, wind, sea, shores, tree, hill, country, and finally, landscape itself. The physical aspects of the metaphor, however, don’t describe her physical being, but rather the ‘landscape’ of her mind or even her personality. Her landscape is never still. Rather it is shifting season by season, never remaining settled long enough for him to explore and inhabit. As a metaphor representing her mercurial, quixotic personality, this liquid landscape is perfect.

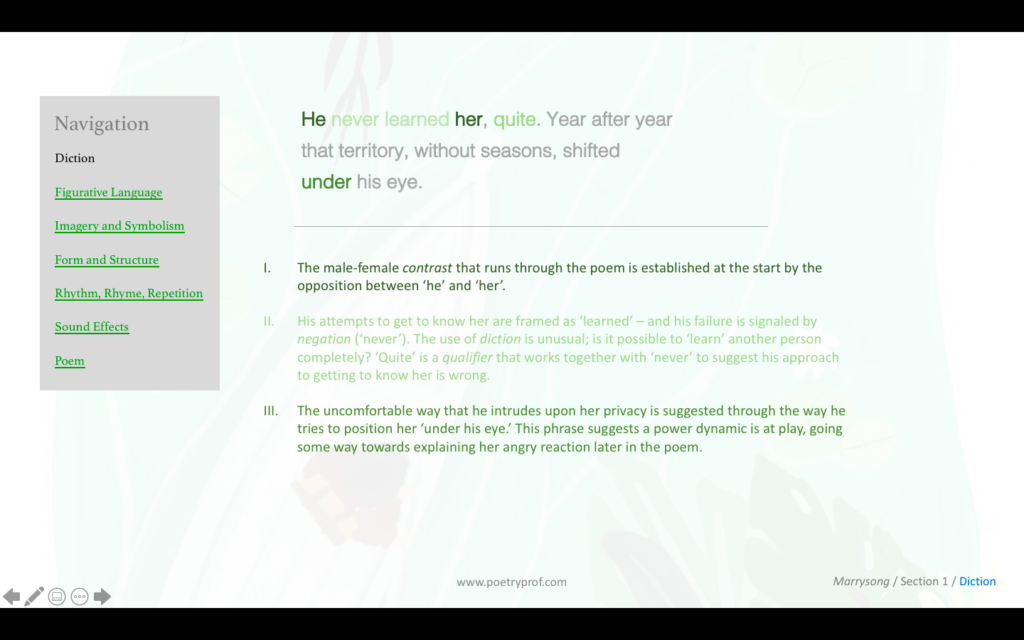

On the other side of the extended metaphor, ‘he’ is depicted as a kind of emotional cartographer, trying to explore her personality, and thereby map, chart or understand it. ‘His’ aspects of the poem include: territory, charted, map, roads, journey and geography. He never learned her, quite establishes the tension between he/her at the heart of the poem: the two words are oppositions and the push-pull between them will play out over the whole poem. All kinds of contrasts come into play here: he seems logical where she seems emotional. He is proactive, she reacts. He seems to want to build something whereas she can be quite capriciously destructive. Or so it might seem unless you read carefully.

As a result of his attempts to ‘learn’ her, you might sense an interesting dynamic between the two: He never learned her, quite doesn’t only set up the binary male-female opposition, but also subtly establishes the power dynamic between them: think back to your early lessons on grammar and sentence structure and you’ll recognise subject-verb-object. This, grammatically, ‘objectifies’ her. You might also remember active vs passive tense. He… learned her and later He charted positions him as the active one – perhaps too active. Little details develop the implication that his advances are not always welcome, he’s trying too hard to pin her down. Look how determined his explorations are, year after year, and the way he tries to position her under his eye. Scott might be suggesting that overeager, overbearing ‘explorations’ like this might feel more like invasions to the other person; a territory can be said to be occupied, after all. No wonder her defensive instincts are to throw up a wall of anger to hide behind.

Three times the poem describes her using diction that is associated with stone: quarried, walled and stones. Describing someone as having a ‘stony’ personality is another way of saying they are impenetrable, hard to know. But I particularly like the associations of quarried, which may suggest he has been digging too hard in his attempts to get to know her better. It’s a vicious circle: she’s hard to know, so he digs persistently, so she hardens herself even more. This cause-and-effect idea, in which he instigates her extreme reactions, is later made apparent by the line: He charted. She made wilderness again. The effect of his constant poking and prodding is emphasised by the caesura (full stop in the middle of a line of poetry) which not only separates He from She (echoing the opposition established in the very first line) but also suggests her negative reaction is a natural result of his behaviour. It feels like a cat and mouse game. He advances. She retreats, trying to keep a safe distance between them both. Viewed like this, it’s not capricious at all, but an attempt to protect her own sense of identity.

Most frustrating to him is her changeability. As soon as he thinks he gets close it’s like she metamorphoses into something else. The first hint of this is when the poem says she shifted, a word which also brings to mind the phrase ‘shifting sands,’ which can be used to describe the way the foundation of something (like a marriage) may not be solid. After this you can pin the poem on the wall and throw a dart at it – you’ll more than likely hit something that suggests her quicksilver personality: diction (change, suddenly, each day new); repetition (all, all… reveals his frustration; new is used twice); enjambment (by which one line runs quickly into another suggesting something that is hard to pin down); caesura (full stops are placed unexpectedly, rarely at the end of lines) juxtaposition which positions wildly differing words next to each other (examples include: cool water laughing where before there were stones in her voice; rain becomes faultlessly calm). It’s actually quite astounding how Scott makes all of these poetic techniques work together without his poem seeming overcrowded or forced.

In fact, there’s more! Read the poem out loud and hear sounds expressing fluidity, relating to the personality of someone who cannot be caught or pinned down. Firstly, the poem avoids a conventional rhyme scheme, saving any rhymes until linking true in line 8 with new and grew in lines 11 and 12. Excepting the final couplet, these are the only full end-rhymes (rhyming words placed at the end of lines); in most of the poem Scott instead uses half-rhymes and internal-rhymes; walled/cool, again/rain and country/jaunty are all hidden away and difficult to pin down. This mirroring of her personality through rhyming techniques is an example of the way form and content can be matched by a fantastic writer.

Let’s take a closer look at one section in particular:

An hour he could be lost

in the walled anger of her quarried hurt

on turning, see cool water laughing where

the day before there were stones in her voice.

This short passage makes liberal use of a kind of alliteration called liquid. Created by combinations of L, R and W, it’s brilliant at suggesting fluidity: her defining characteristics. You can see for yourself how many liquid sounds flow through the phrase cool water laughing where… The sounds seem to blend and shift, like, well, cool water. As well, this passage features hard C alliteration in cool and quarried. Called guttural, this sound can be used to express pain: his pain at finding himself repeatedly rebuffed; her pain at his constant needling and poking.

Another benefit of the extended metaphor is it gets us to compare the excitement of a journey into mapped and charted territory against a journey that throws up unexpected sights. The phrase jaunty helpless journey illustrates this tension well, containing an oxymoron: jaunty suggests fun where helpless contains an element of panic at having to venture into the unknown! But, by this time, you’ve probably already noticed ‘he’ becoming a bit more relaxed, a bit more open to seeing things from ‘her’ point of view. Nowhere is this clearer than in the lines:

the shadows of her love shortened or grew

like trees seen from an unexpected hill

These lines assert the importance of perspective in a relationship. It is partially perspective that makes her seem so changeable. He stands on a hill and, as time passes and the sun tilts in the sky, of course shadows lengthen and change. In this image, the trees symbolize love. Despite her outward displays of quixotic emotion, her interior landscape remains unchanged: love is constant. The trees don’t shorten or grow – only their shadows do.

By the end of the poem, it seems ‘he’ has learned this lesson. Following the poetic tradition of the volta or turn (by which the poem shifts perspective, changes in tone, or presents a counter argument) the final three lines present a drastic change. The turn is marked by both a rare full stop at the end of line fourteen (after journey) and the connective so which indicates cause and effect again. But this time the pattern is reversed: he’s the one who reacts to her behaviour by easing up, backing down and changing his approach. Taking a closer look at the form of Marrysong brings up one or two interesting observations: the firt is that the turn occurs after the fourteenth line. Without the turn Marrysong would be easily identifiable as a conventional sonnet. The last three lines – in which the man changes his behaviour – are a kind of ‘coda,’ which stretches the sonnet to seventeen lines. There are many historical precedents for sonnets of more than fourteen lines: the name for a sonnet of more than fourteen lines is a stretched sonnet.

The key is the word wondered, which is a deliberate pun (or play) on the word ‘wandered.’ Figuratively, he stops trying to chart and map her, ceases his aggressive explorations, and becomes still (stayed home). Wondered transforms a physical action into an emotional one. Instead of moving, he contemplates, thinks, and accepts. It’s ironic that once he stops searching, he actually finds what he’s looking for. Another irony that I’m sure hasn’t escaped you: despite his frustration at the way she constantly changed, it’s only through accepting the need to change himself that he discovers more about her! The eventual success of their marriage isn’t assured; but success is heavily implied by the rhyming couplet that closes the poem. Previously devoid of true end-rhyming pairs, the couplet suggests a closing of distance between them, union, reconciliation and co-operation between the two people from here on out.

So, the poem is ultimately redemptive: up until the volta, Marrysong had been suggesting that it’s impossible to truly know another person, even the one with whom you are closest and most intimate. The last lines, in which he begins to find his way among the landscape of her mind, don’t totally reverse this idea; but they do suggest that you can discover how to get along with and accept that other person for who they are, rather than try to impose your idea of who they should be upon them. The poem is reluctant to make judgements about who is right and wrong, although the way the narration is more aligned with ‘his’ thoughts might encourage us to see his mistakes more clearly than hers. Unlike those fairy-tale romances, Marrysong paints a nuanced picture of a relationship that changes from line-to-line. One moment it’s warm with laughter; the next moment filled with hurt and anger. It might be interesting to note your own responses to the couple’s predicament: on first reading, did you sympathise with the man who clearly loves and wants to get to know his wife better, but is maybe a little overbearing in his behaviour? Or are you on the side of the woman who wants to keep a little distance from her husband, perhaps reasonably, but behaves in unpredictable ways? Fortunately, the end of the poem saves us from having to choose. Reconciled at last, by the end of the poem he has learned what he had to learn after all.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Sonnet 43 by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

After years of living as an invalid, Elizabeth Browning eloped to Italy with her lover, Robert Browning, where they were married in secret, a romance that inspired what some believe to be the greatest love poem of all time, beginning How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Ways –

- Sonnet Reversed by Rupert Brooke

Beginning with the couplet that normally ends a sonnet, Brooke’s poem begins with an emotional punch – but look what happens to the language as the sonnet progresses to discover his true feelings about marriage.

- Uncle Time by Dennis Scott

Written in ‘nation language’ (Jamaican Creole), this is a classic in Jamaica because it was one of the first occasions on which a literary heavyweight like Dennis Scott had used this dialect to publish.

- Song of Divination by Li Zhiyi

Like Marrysong, this 11th century poem contemplates love through geography. Translated from the original Chinese, the poem’s two brief stanzas imagine the speaker and her love living at different points along the Yangtze, the huge river that divides China north from south. Although they are not together, they drink from the same river and this thought comforts the speaker.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Marrysong at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining conceits and extended metaphors in Marrysong and other poems.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What did you think of Dennis Scott’s Marrysong? Do you feel it is a more honest presentation of a marriage than you find elsewhere? Which aspects of the relationship felt real to you? Do you agree that the man is responsible for his wife’s drastic reactions? Leave your feedback, suggestions, questions or thoughts in the comments section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Poetry Prof has become my favourite site for analysis of poetry. You are doing your job exceptionally well and making the understanding of poetry effortless and enjoyable. The addition of images adds a quirky touch that breaks the monotony of the prose. Thank you for all your help.

Thank you so much! I agree about the use of images; analysis can be dry and hard to follow when it’s unbroken prose. You might like to find us on Instagram. We post nuggets of analysis accompanied by more of Alicia’s lovely images each day.

I love this analysis. I definitely recommend this website. Thank you for making it and also including fantastic illustrations:,-)

Thank you so much for all your help!! I got an A* for IGCSE English Literature after getting a B in my mocks. Your poetry analysis and cute illustrations made studying poetry fun and interesting! Just reading all your posts 3 weeks before the exam made me learn way more than everything I had learnt at school over the past year. THANK YOU FOR EVERYTHING 💗

Hi Freya,

Thank you so much for taking time to write – I’m so happy we were able to help you get your A*. Many congratulations and best of luck in your next steps.