Charlotte Smith negotiates the shifting sands of life in this dark and stormy sonnet.

“A lady to whom English verse is under greater obligations than are likely to be either acknowledged or remembered.”

William Wordsworth

Born in 1749, Charlotte Smith’s life was marked by the early death of her mother and the profligacy of her father. Being terrible with money, when she was 15 he married her off – apparently against her will – to a West Indies trader called Benjamin Smith. By her own account, hers was not a happy marriage, partly because he too was profligate and wasted much of his family’s wealth: in 1783 Benjamin was sent to debtors gaol – and, as was customary at the time, she accompanied him there! They would later flee to France to avoid a repeat sentence, where she was to leave him in 1787 and return to England, supporting her 13 (!) children alone by writing. She published numerous volumes of poetry and novels, some of which were inspired by her experiences of the revolution in France. She was, however, most famous for her sonnets, of which Written Near a Port on a Dark Evening is a great example.

Huge vapours brood above the clifted shore,

Night on the ocean settles dark and mute,

Save where is heard the repercussive roar

Of drowsy billows on the rugged foot

Of rocks remote; or still more distant tone

Of seamen in the anchored bark that tell

The watch relieved; or one deep voice alone

Singing the hour, and bidding “Strike the bell!”

All is black shadow but the lucid line

Marked by the light surf on the level sand,

Or where afar the ship-lights faintly shine

Like wandering fairy fires, that oft on land

Misled the pilgrim – such the dubious ray

That wavering reason lends in life’s long darkling way.

Given her dramatic biography (including the disappointments and betrayals she suffered by her father and her husband leaving her to fend for her large family mostly by herself) it’s no surprise that this poem describes the experience of being stranded on a strange beach in the dark, surrounded by confusing sounds, with only shadowy and ephemeral lights to guide the way – lights that could just as easily lure you into the sea as guide you home. In actual fact, this scenario was to occur several times in her published poetry. These words are from her Elegaic Sonnets, written while accompanying her husband in prison:

Slow in the wintry morn, the struggling light

Throws a faint gleam upon the troubled waves

Their foaming tops as they approach the shore… catch the beams

Of the pale sun…

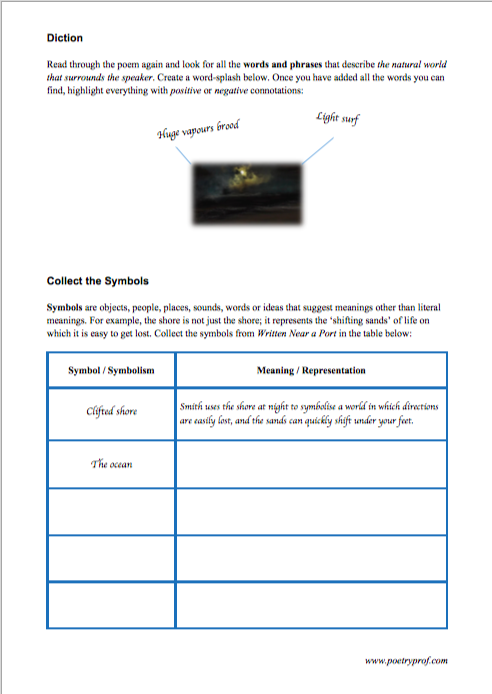

Smith certainly had a thing about beaches, especially the danger of beaches at night, or walking too far out near the sea; this fixation gave rise to what must be my all-time favourite title for a sonnet ever penned: On Being Cautioned Against Walking on an Headland Overlooking the Sea Because it was Frequented by a Lunatic. To Smith, beaches seem to represent the ‘shifting sands’ of life, where one false step can lead to disaster. It’s easy to see how this could be a metaphor for her life situation; always struggling to stay one step ahead of the debt collector, living day-to-day by the skin of her teeth. In this poem the world seems illusory, as if the speaker cannot trust her own senses (particularly the things she sees and hears). She needs guidance and leadership – but is ultimately left to navigate life’s long darkling way by herself.

This poem’s title isn’t quite as mind-blowing as On Being Cautioned…but it’s still evocative: Written Near a Port on a Dark Evening could be the noir-ish title of a mystery thriller. The first couple of lines take the cliched setting of ‘a dark and stormy night’ and run with it to create a deeply mysterious and threatening atmosphere. Firstly, she personifies the wet night with carefully chosen descriptions: brood… dark and mute. ‘Brood’ especially has sinister connotations, as if the dark storm clouds settling on the beach are fuming angrily over some unseen grievance. We don’t know what it is – the night is mute and keeps its cards held closely to its chest. It ain’t giving no one no help. The word clifted is a lovely economical description which complements the sense of imminent danger; in just one word, images of sharp edges and imprisoning rock walls are summoned.

The dark and the ocean are the principal dangers here; trying to navigate the dark beach might lead to disaster. So our speaker tries to orient herself using her sense of hearing instead. But the night has other ideas. She is surrounded by repercussive roars. Imagine standing on a windswept beach at night, not being able to see. You’re straining to hear, but the sound of the pounding waves bounces off the cliffs and rocks all around you. The word ‘percussive’ means a strong steady beat, it connotes the pounding of drums: add the prefix ‘re-‘ and you get the crash of waves echoing incessantly, drowning out other sounds. The repetition of ‘R’ alliteration in repercussive roars and remote rocks helps strengthen the impression of a strong repetitive noise echoing back at you, while sibilance (repeated S sounds) evokes the ceaseless noise of the sea as well. Read the whole first stanza out loud to get the full effect – it’s pretty disorienting. By the time we’ve read to the end of the first four lines there’s a pretty strong sense that the human world inhabited by the speaker and the natural world (the sea, shore, rocks, foggy vapours and dark night) are in opposition.

What’s this though? Recognizable sounds are audible through the tumult. Somewhere out in the darkness there’s a ship (anchored bark) with seamen securing her against the waves and calling out the time (singing the hour). These men, other members of the human world, represent the promise of companionship, a friendly voice to guide our speaker safely through the night. The problem is they are remote and distant, their voices only faintly heard. To help us imagine all this from the speaker’s perspective, Smith uses alliterative sound patterns to create a cacophony of sounds, some of which (in particular the R and S sounds we’ve already seen) mix together to evoke the roar of the sea, others of which cut through this background noise, just like the voices of the distant seamen and the occasional struck bell. Guttural (C, CK, G) and plosive (P, B) sounds are especially good for this, so Smith makes sure to scatter these strategically throughout the octave: repercussive, billows, rugged, rocks, anchored bark, deep, bidding, strike.

The rhyme scheme (ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG) and line separation between the octave (first eight lines) and sestet (final six lines) make this a Shakespearean sonnet. The break signals the volta, otherwise known as the turn, which is a shift in the perspective of the speaker, a counterargument or some other change in the direction of the poetry. (Shakespeare often ‘turned’ as late as the final couplet, but in many sonnets the turn appears elsewhere, such as between the octave and sestet). Sometimes the turn is marked by a connective (‘yet,’ ‘thus,’ ‘alas,’ ‘but’ and the like); Smith’s ninth line contains the word but. After this you can see the change – literally – as the speaker finds a lucid line along the beach. Lucid means ‘clear’ and is the first moment in the poem where the speaker can orient herself visibly. I don’t know if you’ve been on many beaches, but you can often see the tide line marked by the light surf on the level sand: stones, seaweed, a foamy deposit and suchlike often make the tideline visible.

You may feel a certain calming while you read these lines, the hectic blend of shadows and sounds from the octave resolving into something calmer and more patterned. Take a look at the arrangement of L and S sounds in the lines below:

All is black shadow but the lucid line

Marked by the light surf on the level sand

Or where afar the ship-lights faintly shine

You can see alliteration doing the heavy lifting here. The balance of the sounds is regular, L,S,L,S… the alternations recreating a steady one-two rhythm, linked to the ebb and flow of the waves and bringing to mind the steady inhale-exhale of calm breathing. The de-dum, de-dum rhythms of iambic pentameter create these effects too. Other sounds in these lines are similarly calming: F, for example, in surf, afar and faintly or the liquid alliteration (L, R, W) combined with assonance in all, shadow, marked, surf, or, where and afar. Where the octave created cacophony, these lines create euphony.

Just when you feel calm and safe for the first time, though, Smith pulls the rug out from under your feet by throwing in the possibility that the guiding light is a trick. In the final three lines of her sonnet, she compares the ship lights to fairy fires, supernatural lights which lure people (she uses the word misled) into further confusion. It’s hard to read these lines and not think of Smith’s personal circumstances, repeatedly let down by those whom should provide guidance: her mother, father and husband. Once again alliteration plays its part: F sounds reappear in fairy fires, but where before they were calming, now they are associated with devilry and trickery.

Smith’s state of confusion is evident too in the lexical field of the poem. Words like distant, afar, and remote suggest she feels alone, far from help and safety. Wandering, faintly, dubious and wavering all suggest a lack of conviction and certainty, as if nothing in her life – not even her own reason, which she supposes is only lent for a time – can be trusted. The world is black or dark, consisting of shadows, drowsy billows, and vague, tricky lights. Her mindset is best expressed through the metaphors that close her sonnet: life is one long darkling way full of unseen dangers, and she refers to people as pilgrims; those who must fulfil a challenging religious obligation. Is this how she views her own life? It’s a fairly bleak outlook, as is the suggestion that she can’t navigate it safely to the end.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- On Being Cautiioned Against Walking on an Headland by Charlotte Smith

Mentioned in this blog because of it’s awesome title, there’s a lot more going on in this poem as well. Featuring some of Smith’s favourite motifs such as wild and stormy weather, pounding waves and a sense that one is lost in life. Read it here and compare it to Written Near a Port for yourself.

- Ode to a Watch at Night by Pablo Neruda

Originally written in Spanish, this is an ode to a wrist watch, literally. But it’s also about time, companionship, the forces and rhythms of nature. Like most of Neruda’s poems, reading this is a special experience.

- Suicide Off Egg Rock by Sylvia Plath

In this poem, the speaker watches as somebody prepares to throw himself into the sea. All around him on the beach life is bustling, but he purposefully turns his back on the world. The poem interestingly implies that it is in the moments before death that he feels most alive.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Written Near a Port on a Dark Evening at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to explore our bespoke study bundle for this poem. Costing only £2, the bundle includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Smith’s use of the sonnet form.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy Charlotte Smith’s sonnet, or is her vision of the world a bit too bleak for you? Do you agree that the poem suggests that life is always full of doubt and uncertainty, or do you find it more hopeful? Share your ideas and suggestions for other readers in the comments section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.