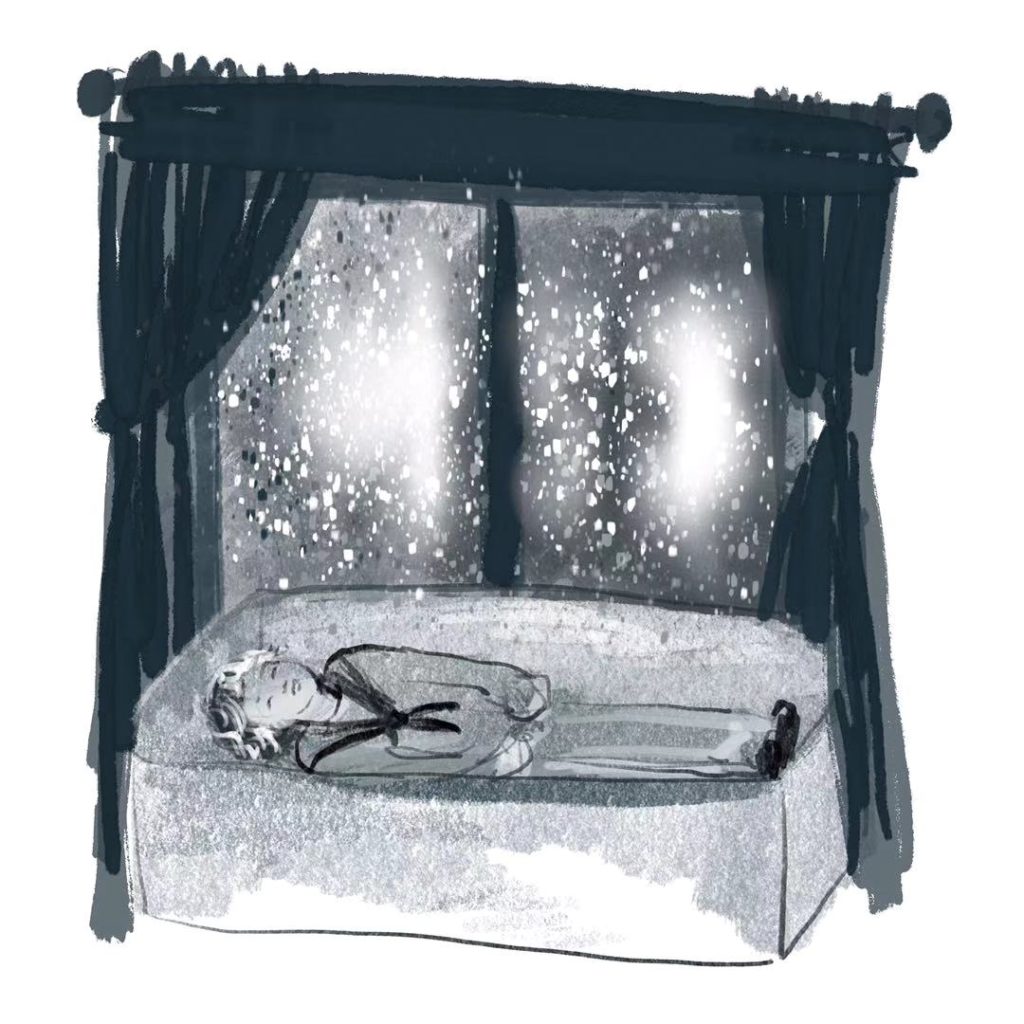

Seamus Heaney shares with us a sad memory from his childhood.

“… the most skilful and profound poet writing in English today.”

Edward Mendelson (NYT Review of Opened Ground)

Seamus Heaney is one of the most recognisable names in English-language poetry. It’s quite possible that you could hear his writerly voice as a child, study him as you get older (his poems are often anthologised or selected for GCSE and A Level study) and come to regard him as an old familiar friend through your adult life. Heaney won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995 and turned down the position of Poet Laureate when it was offered to him, possibly because he regards himself as Irish, not British: after lunching with the Queen he said, “I have nothing against the Queen personally”; but in 1982 he published the lines, “My passport’s green/ No glass of ours was ever raised/ To toast the Queen.” Before his death in 2013 he wrote about Irish community life, people’s connection with the land (Storm on the Island; Bogland ), politics and history (particularly The Troubles), his own rural upbringing and journey to becoming a writer (Follower; Digging; Personal Helicon). A recognisable Heaney trait is filtering subject matter through a child’s looking-glass lens. His most famous poems (Death of a Naturalist and Blackberry Picking) are directly concerned with childhood, in particular the loss of childhood innocence as one grows older. Mid-Term Break (from the collection Death of a Naturalist, written in 1966) shares this theme, which it explores through recounting an experience from the poet’s own history; when Seamus Heaney was still a child, his younger brother Christopher was hit and killed by a car:

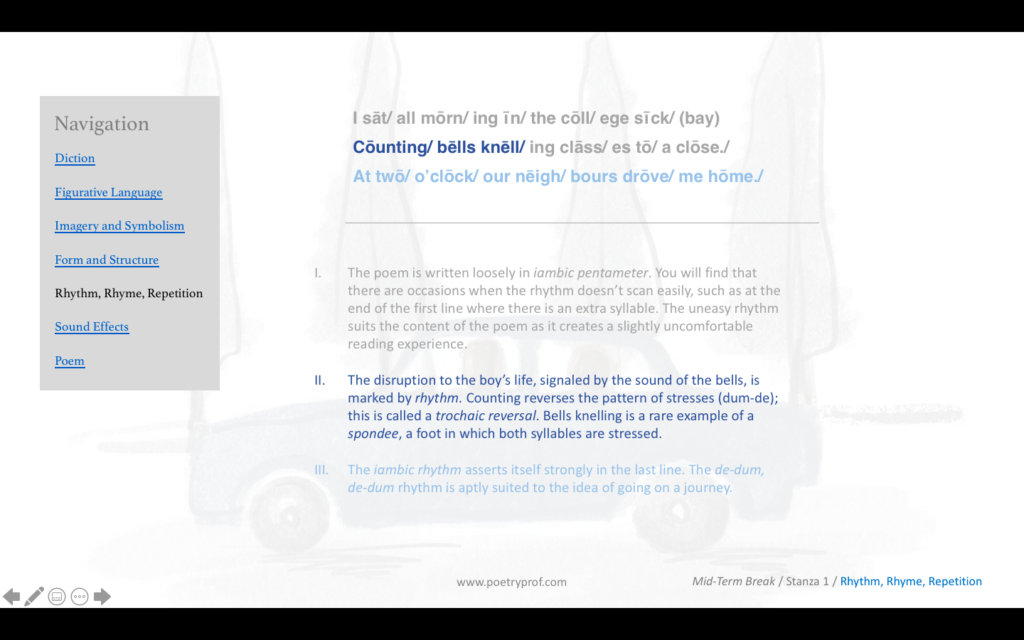

I sat all morning in the college sick bay

Counting bells knelling classes to a close.

At two o'clock our neighbours drove me home.

In the porch I met my father crying —

He had always taken funerals in his stride —

And Big Jim Evans saying it was a hard blow.

The baby cooed and laughed and rocked the pram

When I came in, and I was embarrassed

By old men standing up to shake my hand

And tell me they were 'sorry for my trouble'.

Whispers informed strangers I was the eldest,

Away at school, as my mother held my hand

In hers and coughed out angry tearless sighs.

At ten o'clock the ambulance arrived

With the corpse, stanched and bandaged by the nurses.

Next morning I went up into the room. Snowdrops

And candles soothed the bedside; I saw him

For the first time in six weeks. Paler now,

Wearing a poppy bruise on his left temple,

He lay in the four-foot box as in his cot.

No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear.

A four-foot box, a foot for every year.

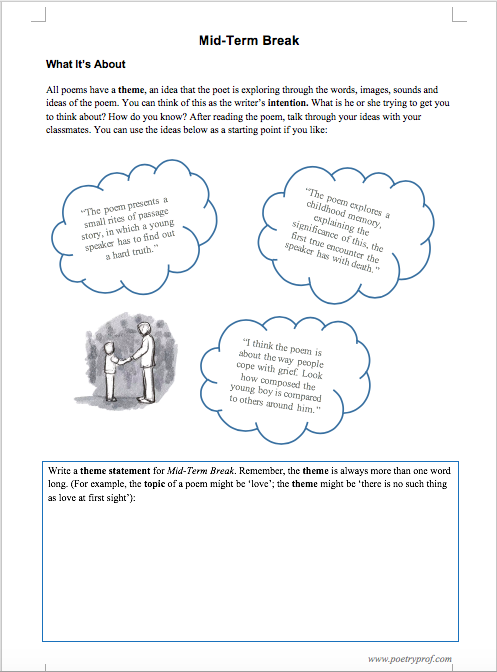

On first reading, apart from obviously being written in stanzaic form (which we’ll get to later) the poem is actually quite, well… unpoetic! In some respects, it’s more like a narrative in the way it tells the story of Heaney’s discovery of his brother’s death. The poem contains clear narrative features such as the building of suspense (see how the poem counts down time for us: two o’clock, ten o’clock, next morning), direct speech (‘sorry for my trouble’) and even brief characterisation: I met my father crying – he had always taken funerals in his stride – In a way, Mid-Term Break is a narrative: it follows a well-worn narrative pattern called the ‘rites of passage’ by which a young person must leave the safety (and ignorance) of childhood and undergo a journey of discovery. Along the way, the child acquires special knowledge and undergoes a transformation, shedding the childish self like a snake sheds a skin and emerging as a new, older and wiser person. That’s why the poem begins in the college sick bay, which represents the safe world of a child; soon the boy is taken home, where he must pass through various adult hands, all ushering him towards the place where he will discover the truth hiding at the heart of the poem. The room in which he encounters his brother – and has his first experience of the reality of death – is the place where this awful knowledge is contained and it is no accident that he is left alone to experience his first taste of the adult world all by himself.

At the start of the story, though, the boy is unaware of what lies in store; both he and we, the readers, wonder what is happening to take him out of class and home from school early. There are a couple of clues: knelling is a word used only to describe the sound of a bell; it is especially associated with bells that ring to proclaim somebody’s death. In a ‘rites of passage’ story, in order for a person to grow and change their childish self must symbolically die. As well as foreshadowing the death of the speaker’s younger brother, the bells he hears counting down classes to a close also signify the death of his childhood and induction into the adult world. Alliteration plays a part here. Look at all those hard C sounds in the line above, and add college sick bay and two o’clock. This kind of alliteration is known as guttural. Guttural is good at exposing negative emotions, and also resembles the ticking of a clock, counting down the time until the boy must experience the truth that is waiting for him.

When the boy arrives home he meets his father standing on the porch. Here is an example of a ‘threshold’: a boundary between two ‘worlds.’ If the school represented a ‘safe’ place where he was sheltered and protected from hard truth, his house is the site of his revelation and the place where he will be exposed to the truth about how things are in the ‘real’ world. The porch is the dividing line between these two ‘worlds.’ His father (and Big Jim Evans) function as symbolic gatekeepers. They know the truth, but do not reveal it to the boy, except through cryptic clues such as it had been a hard blow, language that suggests concealed emotion and also echoes the accident that killed his younger brother. Instead they usher him inside, where he will be passed from hand to hand, until he reaches his brother’s bedside. At this point, he will be by himself and have to face the reality of the world alone.

Just as in a good narrative, perspective is a crucial reason why the poem works so well. The speaker’s youth and naïvete brings a touch of irony into the poem. Each stanza gives more little clues, information hiding in plain sight, that the boy’s youth prevents him from fully understanding. But as readers looking in from outside, it’s relatively easy for us to piece together the puzzle at the heart of the story. The first puzzle-piece is probably the wordknelling in stanza 1. It’s the kind of word a young boy wouldn’t know (the adult writer uses it as he looks back on his childhood experience). In stanza 2 – embedded inside two hyphens as an extra detail – is the admission that the speaker’s father had always taken funerals in his stride. In the third stanza old men stand up in formal way to shake my hand, and in the fourth we can infer from the whispers that informed strangers I was the eldest that something has happened to a member of the boy’s family. By the time the ambulance arrived with the corpse most readers will be prepared for the awful knowledge of the boy’s younger brother’s tragic accident.

Written about a childhood time when nothing in the adult world makes sense (you can almost hear the boy thinking, ‘Why are they whispering? Why are these old men standing up to shake my hand?’) the voice of the speaker conveys Heaney’s thoughts and curiously detached feelings through this bewildering day. Interestingly, most of the diction in the poem is cool, calm and collected, and the young speaker comes across as matter-of-fact above anything else. Read the poem again to try and find examples of emotive language – it’s tough, right? That’s not to say the poem isn’t emotional, but emotion comes more from the reader’s grasping of the situation than from the poem itself. The boy himself reports everything with simplicity: stanched and bandaged is quite clinical; I saw him for the first time in six weeks a simple matter-of-fact statement. The clinical, detached tone aptly conveys the way a young boy might approach his first encounter with death. Too young to really grasp the significance of events, he reacts in a way that might even be construed as indifferent.

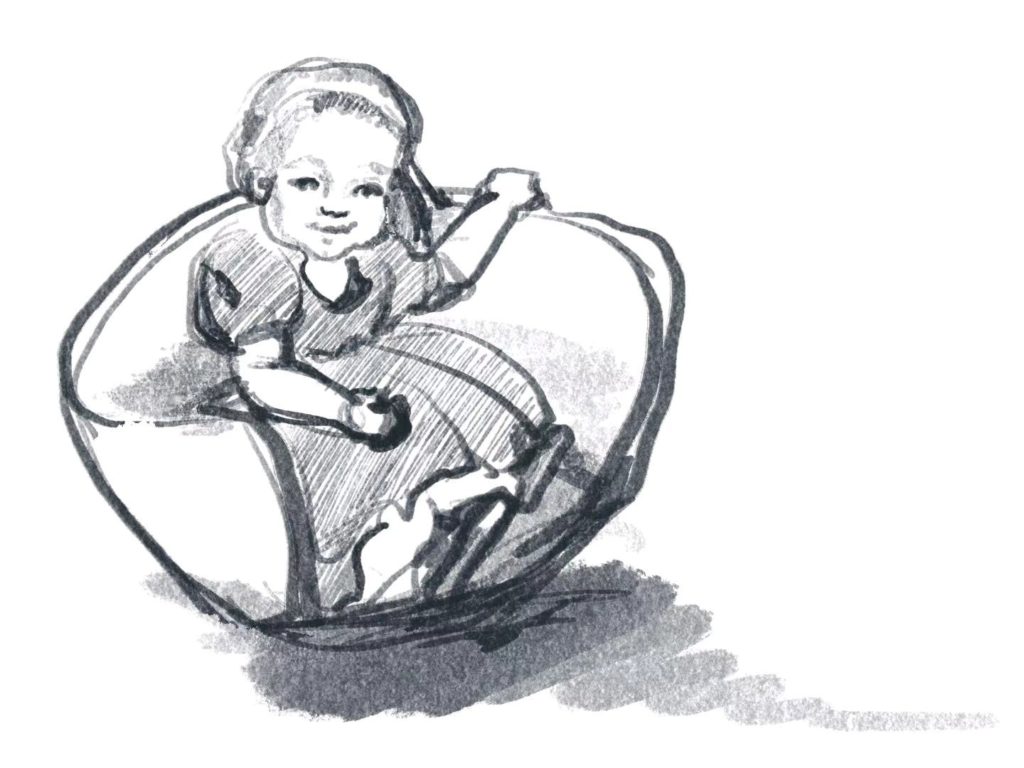

Something the poem explores wonderfully well is the stoic, masculine way that men deal with their emotions, particularly grief. The speaker’s father had been crying, but the poem is quick to point out that normally he takes things in their stride. Big Jim Evans is unable to use straightforward language when talking to the young boy and euphemises his feelings as a hard blow. Euphemism is language that is uses to disguise, or avoid, speaking hard truths and it’s again ironic that somebody big, when faced with a harsh reality, finds it difficult to confront. Old men stand up to shake my hand reveals how formality and custom are used (again by men) to manage difficult emotions. Whispers is an onomatopoeia that conjures the sound of people talking around him, even behind his back, but hesitant when it comes to admitting the truth. The mother, true to type, is permitted to cough out her angry tearless sighs. She has been exhausted by her outpouring of emotion: by contrast, the men keep theirs firmly shut away inside. A detail that throws the men’s stoicism into sharp relief is the mention of the baby who cooed and laughed in the pram. The contrast of such unknowing, innocent behaviour with the reserved and awkward behaviour of the adults only reinforces the formality of their actions.

According to the poetic tradition of the turn, or volta, at a certain point in a poem the focus shifts, the tone changes or a counterpoint is presented. Mid-Term Break’s turn is disguised by form, hidden inside the fifth stanza. After the description of mother’s sighs our attention is taken away from the reactions of those gathered in the house and placed onto the ambulance, there to deliver the body of the speaker’s younger brother. At ten o’clock is the subtle marker used to make this change. After this point, the poem homes in on the boy’s experience only and we are with him through the terrible walk up the stairs, into the room where his brother’s body is laid in state stanched (like the more common ‘staunch,’ this word means to restrict the flow of blood; you can read it to mean ‘cleaned’) and bandaged by nurses. Assonance plays a part in this stanza: the letter A flows through the lines in all kinds of words such as angry, ambulance arrived, stanched and bandaged. Assonance helps manage the tension in the poem at this crucial moment – the boy is only steps away from entering the room himself and coming face to face with his brother after his awful accident.

Once he enters the site of revelation, the poem intensifies its use of imagery. The evidence of his brother’s wound is described as a poppy bruise, the vivid red colour that flashes into our minds when we read poppy contrasts with the white images suggested by paler now, stanched and bandaged and snowdrops (white flowers) and candles soothed the bedside. Like the knelling bells, this use of language comes from the older writer looking back on his childish persona. Look again at the word ‘soothed.’ Flowers and candles are personified to have a calming effect on the scene, and we are invited to compare the ritual trappings of funerals with the formality of behaviour displayed by the men earlier in the poem. The votive candles have a particularly calming effect, bathing the scene in warmth despite the ‘cold’ setting and tone. Perhaps Heaney wants us to think that the objects in the room, the ritual ‘embalming’ of the corpse – like the words and behaviour of the people downstairs – are all bent to the same purpose: the dulling of grief in order to allow men to cope with, and display stoicism in the face of, this ‘unmanly’ emotion.

The importance of ritual is echoed in the poem’s form. Heaney is a traditional poet, and his poetry gestures towards pre-modern times. Mid-Term Break is written in unrhymed tercets (a tercet is a group of three lines) and Heaney employs stanzaic form to echo both the rituals surrounding death and funerals, and to frame the procession by which the boy is brought from his school to the bedside. Try breaking the journey into stages, imagining him passing various thresholds along the way: he leaves the college sick bay, passes through the porch into the main house, and goes up to the room. Each stanza narrows and focuses the boy’s journey until he reaches the bedside, at which point the poem is at its most intimate: just the boy, his brother and us watching from the outside. The repetition of hands is a nice detail helping us to see that he is quite literally passed from hand-to-hand by various adults. He is taken by his neighbour, to his father, through a roomful of relatives and strangers (who shake his hand) to his mother (who held my hand). Finally, he visits the bedside where he is alone. The structure of this journey is like a mini ‘rites of passage’ story, taking a child from a safe, protected world and exposing him to the truth and danger of the adult world.

Suggested Poems for Comparison

- Death of a Naturalist by Seamus Heaney

If you liked Mid-Term Break, you’ll love Death of a Naturalist. The title poem from his 1966 collection (from which Mid-Term Break is taken), the poem’s speaker – Heaney as a child – witnesses an invasion of angry frogs who he describes as ‘the great slime kings.’

- Hide and Seek by Vernon Scannell

If you’ve ever played this childhood game, you might recognise what happens to the small boy in this poem – abandoned in the dark by those he thought were his friends. It’s a little taste of how things really work out in the real world, represented by the eerie way the empty garden seems to look back at him at the end of the poem.

- Little Red Cap by Carol Ann Duffy

It’s not only boys who go on rites of passage adventures. In this reworking of the classic fairytale (Little Red Riding Hood), Duffy imagines herself as the titular heroine, a person with whom it is not wise to mess!

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Mid-Term Break at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining stanzaic form.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

What did you think of Seamus Heaney’s poem? Have you read any of his other works that you could recommend to people who enjoyed Mid-Term Break? How did you feel at the end of this poem – was the revelation a shock to you? Why not leave a comment, start a discussion or share your ideas in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.