A sleepless night prompts Derek Walcott’s intense, introspective poem.

“His work is conceived on an oceanic scale…”

Sean O’Brian in his review of Walcott’s poetry, 1990

Today’s poem struck a chord as, funnily enough, I recently found myself nearing forty years old. The poem unfolds one night while an unnamed speaker is lying awake listening to the rain. He tries to sleep – but something is playing on his mind. Quickly we discover that the speaker is approaching forty years of age. Popularly associated with middle age, forty is a common milestone by which a person should have achieved certain life goals. Nearing that particular turning point myself, I can testify that forty does have a peculiar power to prompt anxious naval-gazing about life, work, worth and the direction things seem to be taking. While I often caution regular readers of this blog about the dangers of assuming the writer and the speaker of a poem are the same person, in some poems the author’s authentic voice can be particularly strong. This is certainly true of Nearing Forty in which we can hear Derek Walcott’s personal voice meditating on his life and career. In an interview given to poetry Review in 1985, Walcott had this to say about approaching middle age:

‘You’re aware of the fact that you have reached a certain stage in your life. You’re also aware that you have failed your imagination to some degree, your ambitions. This is an amazingly difficult time for me. I’m absolutely terrified.’

There are many other autobiographical details hidden in this poem, it would be churlish to doubt: Derek Walcott was a Jamaican poet (sadly, he passed away in 2017) and he dedicates this piece to John Figueroa, a writer and teacher who mentored Derek when he was an up-and-coming talent. Now he’s a successful writer himself, Walcott worries about his artistic talent; his ambition is to master his own poetic style and voice, but he’s afraid that advancing age and the inevitable passing of time means he’s lost the fire and drive of youth; perhaps now his writing will never achieve the standard he’s aiming for. It’s actually comforting to discover that even Nobel Prize winners sometimes doubt themselves and their achievements:

(for John Figueroa)

The irregular combination of fanciful invention may delight awhile

by that novelty of which the common satiety of life sends us all

in quest. But the pleasures of sudden wonder are soon exhausted and

the mind can only repose on the stability of truth...

SAMUEL JOHNSON

Insomniac since four, hearing this narrow,

rigidly-metred, early-rising rain

recounting, as its coolness numbs the marrow,

that I am nearing forty, nearer the weak

vision thickening to a frosted pane,

nearer the day when I may judge my work

by the bleak modesty of middle age

as a false dawn, fireless and average,

which would be just, because your life bled for

the household truth, the style past metaphor

that finds its parallel however wretched

in simple, shining lines, in pages stretched

plain as a bleaching bedsheet under a gutter-

ing rainspout, glad for the sputter

of occasional insight; you who foresaw

ambition as a searing meteor

will fumble a damp match and, smiling, settle

for the dry wheezing of a dented kettle,

for vision narrower than a louvre’s gap,

then, watching your leaves thin, recall how deep

prodigious cynicism plants its seed,

gauges our seasons by this year’s end rain

which, as greenhorns at school, we’d

call conventional for convectional;

or you will rise and set your lines to work

with sadder joy but steadier elation,

until the night when you can really sleep,

measuring how imagination

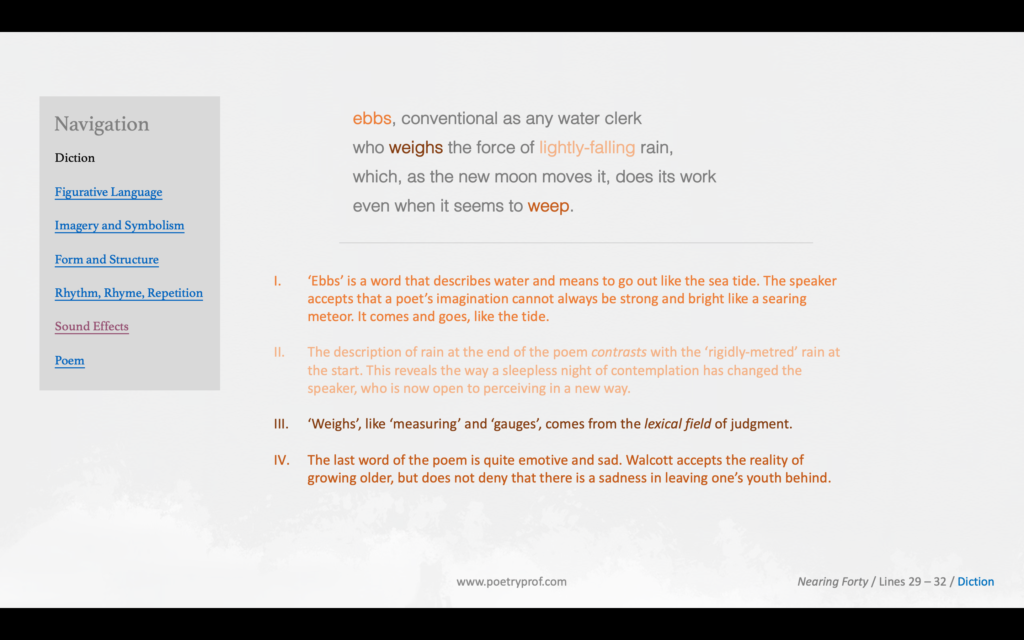

ebbs, conventional as any water clerk

who weighs the force of lightly falling rain,

which, as the new moon moves it, does its work

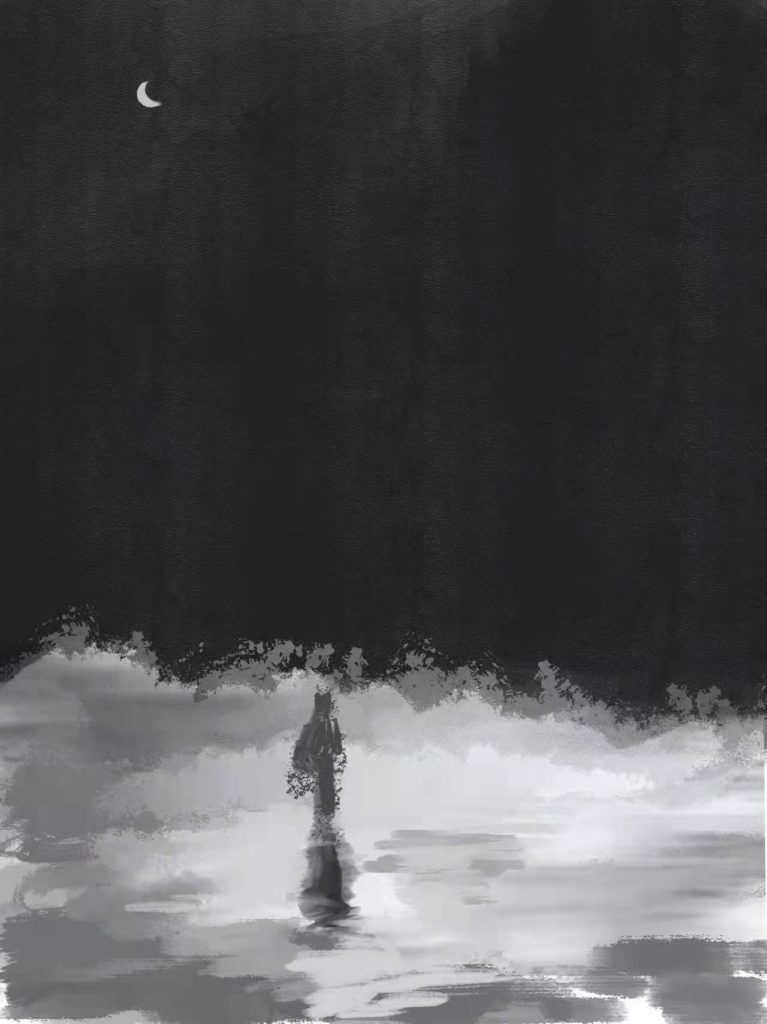

even when it seems to weep.Giving us a little clue as to his themes and concerns in Nearing Forty, Walcott prefaces his poem with an epigraph by Samuel Johnson. An English poet and writer, (you have perhaps heard of him as he was also a lexicographer and wrote the first English dictionary) Johnson was partial to a pithy quote or two. The excerpt Walcott quotes is from his 1765 Preface to Shakespeare. Johnson admired Shakespeare for holding up a ‘mirror to nature’, by which he meant that Shakespeare’s writing revealed truths about the world. The relevance of this snippet to Walcott’s poem lies in the juxtaposition between fanciful invention and stability of truth. These oppositions can be understood as facets of Walcott’s poetry. Throughout Nearing Forty you’ll find scattered references to writing and the creative process (for instance, the rain sounds rigidly-metered as if poetry is falling from the sky), making Nearing Forty an ars poetica; it’s a poem about the process of writing poems! Walcott is pondering his achievement as a poet, and especially worries about the way his own poetic style is developing. He strives to achieve what Johnson called the stability of truth, a quality he recognises in John Figueroa’s writing (he notes Figueroa’s commitment to the truth in line 10). He wants his own poems to be ‘real’ and ‘truthful,’ grounded in the concrete and recognisable world. Walcott worries that the poetry of his youth, while critically acclaimed and demonstrating imaginative flourishes of fanciful invention, was not honest enough. In large part, Nearing Forty is a reflection on his own past work, and a commitment to striving after truth in the future.

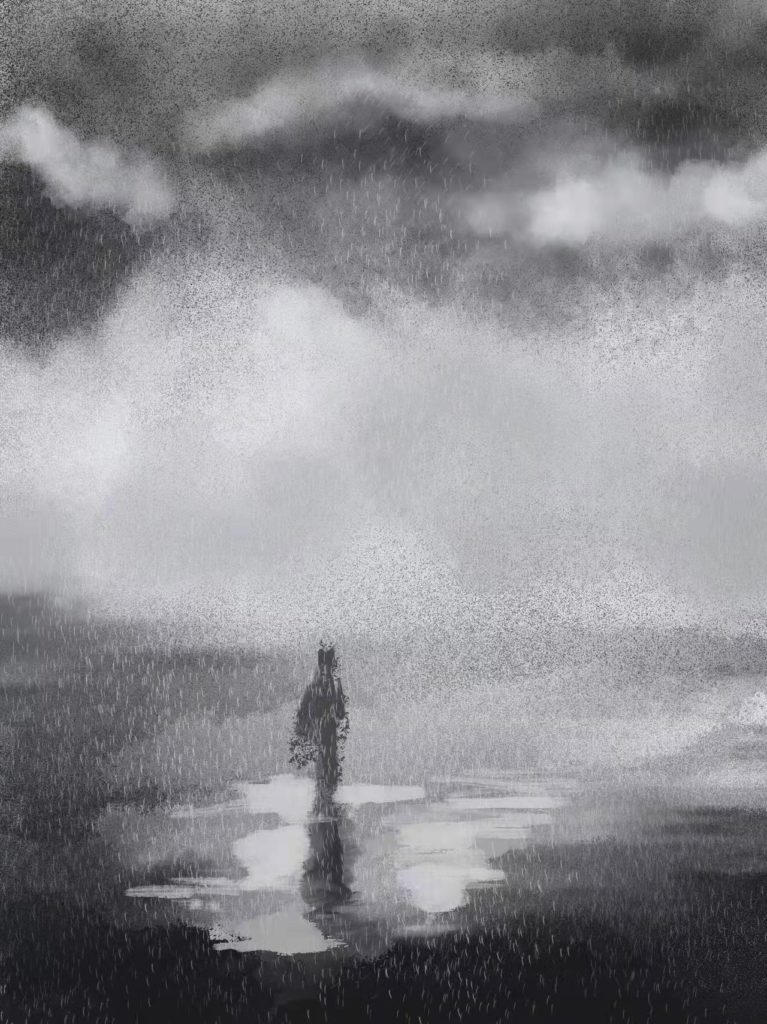

The poem begins with the speaker admitting his uneasiness. He can’t sleep (insomniac) so he’s just lying awake, listening to the rain. If ever you’ve suffered from insomnia, you’ll know it’s more powerful than simple sleeplessness. Your mind turns over and over, playing tricks, homing in on every little creak or squeak and finding repetitive patterns in the small sounds and movements of the night. Walcott’s thoughts intermingle with the sound of the rain which take on a rhythm, rigidly-metred, a description which transforms the rain into lines of poetry falling from the sky. There’s a literary tradition called the pastoral in which elements of the natural world (such as flowers, birds and the seasons) provide inspiration to creative people, like artists and writers. In this case, rain becomes symbolic of poetic inspiration. Walcott aspires to write poetry with the honest purity of the rain-sound; while the words narrow and rigidly-metred may sound like they have negative associations, later in the poem it becomes clear that narrow is associated with the concentrated focus of John Figueroa and rigidly-metred refers to the control that a master-poet has over the form of his language.

After a while, the rain-rhythms coalesce into a discernible message that he’s able to hear; the rain is recounting… that I’m nearing forty. It’s this thought that is filling him with anxiety. He’s been writing for years, and he feels that time is running out for him to develop that honest, truthful style patterned by the rain. The rain’s coolness numbs the marrow, suggesting the rain-sounds are able to penetrate deep inside him. This image is open to interpretation. On one hand, you might feel that the rain provokes thoughts and feelings that he is reluctant to face, and his numbness is a defensive response. On the other hand, you might decide that the image of coolness settling into his bones represents the inspirational or instructional power of the rain. Despite Walcott’s worries that he is running out of time to master his poetics, this line might suggest he is subconsciously ‘absorbing’ the rain’s lessons.

From this simple starting point, Walcott’s thoughts meander. We start to appreciate that, for him, growing older feels like a double-edged sword. As we shall see later, age brings wisdom and clarity to a writer; on the other hand, growing older robs a person of powers and passions, an idea he presents using sensory imagery. The coolness of the rain seems to permeate the opening of the poem; fireless, bleak, false dawn and frosted all connote cold, suggesting that he doesn’t feel the ‘fire’ of youth anymore. He’s also afraid of losing his physical faculties and worries about his fading vision; he imagines a time coming soon when he’ll have only weak vision thickening to a frosted pane. As a poet, vision doesn’t only refer him using his eyes to see, but also his mind’s ability to imagine and visualise. Fading sight, then, becomes a type of metaphor (technically called metonymy) by which a part of something stands for the whole of that thing. In this instance, Walcott’s fading eyesight represents all his abilities as a writer. He’s afraid of losing the ability to see beyond his near – or literal – surroundings. The image of him trying to peer though frosted glass conjures up a feeling of frustration that he’s going to be limited in his ability to perceive the world clearly, something necessary if he’s going to achieve clarity in his work.

That his writing will be hampered by his fading abilities isn’t the only fear to plague Walcott this sleepless night; he worries about the merits of his past work too. In this regard he seems to be his own harshest critic. Again, forty is the pivot point around which everything changes, the day when I may judge my work by the bleak modesty of middle age. The poem is full of words from the lexical field of ‘judgment’: judge, gauging, measuring, just, weighs. The poem implies that age brings with it a certain world-weariness or scepticism that young people don’t feel. Later in the poem, Walcott will call this cynicism and develop the metaphor of cynicism being like a seed planted inside a person; over time it will grow larger and stronger until it comes to dominate one’s world view (deep, prodigious). It is this growing cynicism that will evaluate his life’s work for him, reading it with a bleak modesty and judging it average, meaning ordinary. He’ll admit that his early success was a false dawn, a metaphor revealing his fear of being unable to fulfil his own potential. Once again, sensory imagery (bleak, fireless, false dawn) suggests that the fire and passion of youth fades as a person gets older, or that the sparks of promise in his early poetry never truly burst into flame. I find this idea – of an older, jaded person looking back at himself and his work and finding nothing to praise – relatable. What seems so earnest and heartfelt to a younger person (whether a piece of writing, artwork, musical composition, or any act of creativity) might come across as cringeworthy to an older pair of eyes.

There’s no doubt that Nearing Forty is a challenging read, and one thing that makes it hard to follow is the form of the poem. Written from the perspective of the writer as he lies thinking and thinking, Nearing Forty meanders like a stream of consciousness in one long sentence that flows from topic to topic and thought to thought. Lines run one into another through a technique called enjambment, whereby sentences and thoughts don’t match the lineation of the poem. Read almost any line and see how it ‘falls’ into the next, often without punctuation to help mark the end of a phrase or thought. Using this technique helps Walcott to emulate the way thoughts flow one into another. That’s also why he doesn’t capitalise the first letter of each new line, which is a common poetic convention, nor use any full stops (until the last line). Nevertheless, there is an underlying structure to the poem. To begin with Walcott focuses on himself, using the pronouns I and my. In line 10, a subtle alteration to you signals the moment his mind’s perspective shifts into a remembrance of Walcott’s mentor; John Figueroa. As we have seen, Figueroa was somebody Walcott looked up to, an inspirational teacher, mentor to an entire generation of Caribbean writers including Derek Walcott, and master of his craft. Whether fairly or not, Walcott holds himself up against Figueroa, as if studying himself in a mirror, and finds himself lacking in comparison to a man who he considers to be a genuine literary tour-de-force.

Therefore, as soon as Walcott begins to deliberately compare himself to Figueroa, the poem turns. Up till now, the diction of the poem has been measured, restrained and even a touch grey: average, rigidly, narrow and bleak modesty are all words which characterise the poem’s restrained and contemplative tone. Against this drab and rainy backdrop, the word bled (because you bled for the household truth) strikes with a force that can cut. Bled is a strong word, connoting pain, vivacity and colour. The idea of bleeding for the truth suggests Figueroa was a man who lived his ideals and sacrificed for his art. The poem implicitly juxtaposes blood with rain: Walcott lies sleeplessly seeking inspiration from his surroundings; Figueroa simply felt his poetry pulsing in his blood. There’s no doubt that Figueroa is a role model for Walcott, and he strives to achieve the stylistic power of Figueroa’s language. As we saw from the epigraph prefacing the poem, Walcott admires Figueroa’s work because he sees truth in his poems. He describes Figueroa’s writing as having style past metaphor, as though Figueroa has abandoned all the linguistic trickery that lesser (younger?) writers use to ornament their poems. He respects Figueroa’s writing not because of its flowery ornateness but because of its direct simplicity; simple, stretched and plain he calls it. Don’t be misled by the superficial negativity of words such as these, and wretched, as well. Walcott looks up to and admires Figueroa’s plain commitment to the household truth.

What’s more, he remembers how Figueroa was able to take the most meagre sources of inspiration and work them into such forceful poems. It’s here that the contrast between youth and age is most apparent. Walcott remembers how this humble and quiet man also foresaw ambition as a searing meteor. Once again, this simile from the past is expressed in imagery of heat and light; the line is full of the passion and determination of youth, the ambition to blaze a trail through life the way a comet blazes across the night sky. Consider inspiration being like a searing meteor. This is actually a pretty common way to think about the creative process – that inspiration comes out of nowhere, strikes with immense force and power, and suddenly births epic and memorable works of art and literature. But, as he grows older, Walcott is realising that isn’t how creativity works. If a meteor strikes, well… that’s all well and good, and you can enjoy your good fortune. But if you don’t happen to have your eyes on the sky when that meteor blazes past, what then?

Teachers often give this advice to students: write what you know. As he gets older, Walcott is learning that inspiration exists in the ordinary and everyday, not once-in-a-lifetime meteor strikes. John Figueroa derived inspiration from things around him; a damp match or a dented kettle. Again, Walcott doesn’t make these comparisons disparagingly. He’s admiring that, while time may dim your sight, Figueroa never lost the ability to see deeply with his inner, imaginative gaze. He represents the best of growing old: patience, wisdom and a new way of seeing. That’s why so many of the poem’s visual images depict faint or weak light: for example, as well as describing the channels made by falling water on a flat surface (guttering rainspout) the word guttering also means a flame that burns weakly or is on the point of going out (as in, ‘the candle guttered out’). Sputter is an onomatopoeia describing the weak sounds of a damp explosion or a failing engine. Damp matches produce weak flames, and a louvre is a window covered in wooden slats, letting in little light. Despite these weak and flickering lights – representing how ordinary inspiration is less visible than that blazing meteorite – Figueroa sees with a narrower vision and, as we know, narrow associates with clarity and the ability to focus one’s mind. In other words, Figueroa’s insights are household insights; small but ‘real’ world items he experiences everyday, symbolised by that dented kettle with the dry, wheezing voice. It’s from such humble inspirations (Walcott uses the phrase occasional insights) that Figueroa crafts his extraordinary shining lines.

That’s not to say that Figueroa was immune to the same doubts and fears that plague Walcott this sleepless night. He visualises Figueroa in his own act of remembrance – notice the word recall – of that deep, prodigious cynicism that plants its seed inside everybody. I understand this cynicism to be a strong feeling of self-doubt and uncertainty about the path one has chosen, or the direction things seem to be heading. I think that this part of the poem is very interesting. While he clearly looks up to and admires Figueroa, he doesn’t treat him like a flawless hero. Walcott’s poem suggests that everybody, even great masters like Figueroa, can feel doubt, fear and cynicism, worrying that the work they have dedicated their lives to – in this case writing – is average or even worthless. Walcott worries that this powerful self-doubt might push one to repeat the mistakes of youth. He remembers being greenhorns at school: greenhorns refers to a person who is inexperienced and new; green can represent inexperience and naivety. The mistake he remembers making is confusing the word conventional for ‘convectional’. Once again, a word to do with average, ordinary writing – conventional – is a word Walcott is afraid of. The specific mistake he’s worried about repeating is the substitution of quantity for quality. He imagines this process of judgment as a metaphor from his lessons at school: gauged by this year’s end rain. Don’t forget, the opening line of the poem already established the connection between rain and poetry; so his inner fear is that the success of his life (our seasons) will be measured by the volume of work he produces (year’s end rain) rather than the quality of that work.

Once again, the form of the poem presents a challenge as Walcott reveals that this imaginative pathway was just his anxiety talking. Near the end of the poem he turns once more, resetting his thought-pattern in line 25 using a semi-colon and the word or, signalling for us that he’s about to present an alternative resolution. Instead of allowing age and time to defeat him, Walcott reveals that Figueroa conquered the deep cynicism that is the enemy of creativity. Even as age dimmed his passion, it sharpened his creative faculties. Walcott expresses this contradiction using two oxymorons (a pair of words that do not naturally relate to one another placed side by side): steadier elation and sadder joy. He remembers how Figueroa continued to hone his craft even in old age; in fact, he learned that age steadies one’s mind even as it dampens one’s elation. To be honest, at the end of the poem, even though Walcott continues to use the pronoun you, I have the feeling that he’s really talking about himself. Structurally, this makes sense as well. Loop composition is the technical term for the structure of a poem that returns to its starting point. The last part of the poem seems to cycle back to the start; while Figueroa’s figure loomed large over the middle third of the poem, Walcott ends as he began, lying alone in the dark.

So the poem loops back to the start, with Walcott listening to the rain. I’m sure only an hour or so has passed, but this night has been transformative. Where Walcott was reluctant to face the fact of nearing forty, now he accepts he’s growing older and determines to make use of the lessons age can bring. An example of his new mindset is in the repetition of the word conventional; in line 24, he remembers using the word conventional mistakenly and elsewhere in the poem he’s been afraid of conventionality. At the end of the poem he imagines himself as a conventional water-clerk counting the falling raindrops. He’s realised that only through slow, ordinary processes will he allow the rain to penetrate to a place where he can interpret it. His weighing the force of lightly falling rain symbolises his acceptance of a new poetic process, akin to hearing the dry, wheezing sound of that dented kettle. He doesn’t try to deny the pathos of growing old (seems to weep); but ultimately, he accepts that imagination ebbs (‘ebb’ describes the movement of water away from the land, as in a tide going out) and he’ll have to find his own occasional insights in kitchen kettles, insomnia and rain instead. His acceptance of ageing allows the rain to do its work and inspire incredible works of poetry.

Like the one you just read.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Cetacean by Peter Reading

Part poem about an amazing encounter with a blue whale; part ars poetica about the inspiring power of nature.

- The Thought-Fox by Ted Hughes

Arguably one of the most famous ars poetica, Hughes can’t think of what to write – until the elusive image of a fox jumps into his mind.

- Time, that gnaws at bronze lions and dolphins by Derek Walcott

Nearing Forty isn’t the only poem Walcott wrote concerning time and ageing. In this poem, time acts like a creature stalking a man, who leaves pieces of himself all around Italy… until nothing is left of him, but his name scrawled on a wall.

- Rain by Sean O’Brian

If you want to hear how another writer can make those falling rhythms sound like rainfall, look no further than this brilliant poem. Read the second and third lines out loud and try to hear the beats falling down the page for yourself.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Nearing Forty at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring the poet’s use of figurative images and symbolism

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Derek Walcott’s poem? What is your understanding of the speaker’s transformation? Can you recommend other ars poetica – poems about the writing of poems? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Thank you, again!