Mary Monck ruminates on death and life in this touching verse-letter.

Strange as this may seem, in Japan there is a literary tradition called Jisei, which is poetry composed by a person in the last few hours of their life. Jisei were mostly written by samurai, monks, or members of Japan’s aristocratic class. These poems derived from the Buddhist tradition of contemplation of death. According to Buddhism, death is a reminder that the material world is transitory and that worldly pleasures are ephemeral. Important parts of the Jisei tradition were rumination on dying and an acceptance of death, perhaps in the belief that we will live on in different forms. A famous example is by Taiheiki Toshimoto, who wrote: There is no death; there is no life. Indeed the skies are cloudless and the river waters clear.

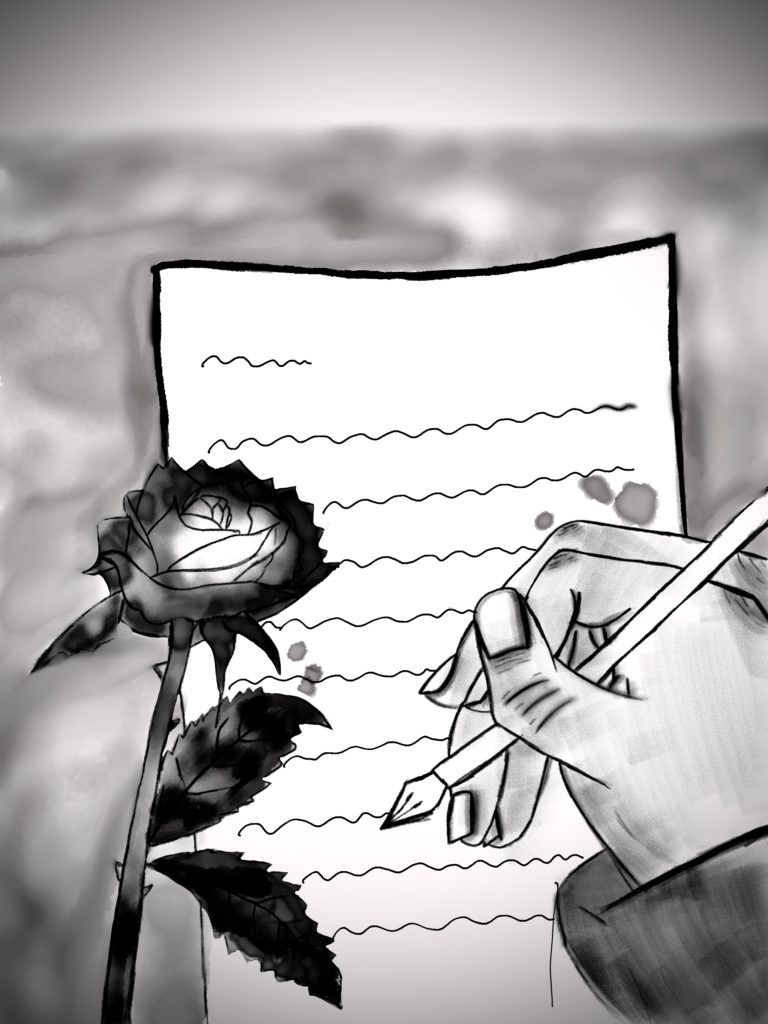

While there is not really a tradition of ‘death poems’ from England, today’s poem is quite special as it was also written a short time before the writer passed away. Mary Monck (who wrote under the pseudonym Marinda) was convalescing in Bath, a town in rural Somerset famous for its healing spa waters. Since Roman times, sick people who could afford to might travel to Bath in the hopes of recovery. Sadly, Bath was to be Mary’s final destination and she died in 1715; at the time her husband George was in London, some hundred miles away. Realising she would never see him again, Mary penned this beautiful verse-letter, to say goodbye and to ask him not to mourn. Instead, she tells him to be happy (rejoice) as her death is not so much the end of her life as merely the end of her suffering:

Thou, who dost all my worldly thoughts employ, Thou pleasing source of all my earthly joy: Thou tend'rest husband, and thou best of friends, To thee this first, this last adieu I send. At length the conqu'ror death asserts his right, And will for ever veil me from thy sight. He wooes me to him with a chearful grace; And not one terror clouds his meagre face. He promises a lasting rest from pain; And shews that all life's fleeting joys are vain. Th' eternal scenes of heav'n he sets in view, And tells me that no other joys are true. But love, fond love, would yet resist his pow'r; Would fain awhile defer the parting hour: He brings thy mourning image to my eyes, And would obstruct my journey to the skies. But say, thou dearest, thou unwearied friend; Say, should'st thou grieve to see my sorrows end? Thou know'st a painful pilgrimage I've past ; And should'st thou grieve that rest is come at last? Rather rejoice to see me shake off life, And die as I have liv'd, thy faithful wife.

While it is usually a mistake to assume the writer of a poem and the speaker of a poem are the same, in this case Mary uses the personal voice, putting her own thoughts and feelings into words. The poem is unequivocally addressed to George Monck, Mary’s husband and lifetime companion. While you might be accustomed to the use of apostrophes in punctuation, a further meaning of the word apostrophe is as a literary technique by which an absent person, or an inanimate object, is addressed as if he, she or it were listening to the speaker. A famous example of apostrophe is from Shakespeare when Hamlet holds and speaks to the skull of Yorrick, his friend dead for many years. Mary’s poem employs apostrophe throughout, addressing George as if he was by her bedside. The first three lines all begin with the word thou, meaning ‘you’ (George) and every time you read thee or thy these words mean ‘you’ as well. Repetition at the beginning of lines has a special name, anaphora, and the effect of this technique, when combined with apostrophe, is to establish the prominence of George in Mary’s mind. She admits: Thou, who dost all my worldly thoughts employ. As she approaches death, her thoughts are all with her husband, an example of hyperbole, which you can think of as a kind of controlled exaggeration. In the next line she describes him as the pleasing source of all my earthly joy as well. Complimenting this are superlatives, which insist that George was the best of all possible husbands. He is described as tend’rest (most tender) dearest and the best of friends. She names him both husband and friend, conveying the idea that George has fulfilled many roles throughout Mary’s life – lover, confidante, companion – and that, even though these roles may change over time, he remains as important to her as ever.

Just as in a traditional Jisei poem, as death approaches Mary uses her remaining time to philosophise about life. She establishes an opposition between earth and heaven, a metaphorical battlefield with her life poised in the middle. Mortality is a property of earth, signalled by the words earthly and worldly. By contrast, heaven is an eternal realm that exists outside the boundaries of time. Here, earthly concerns like pain and terror don’t exist. Earth’s champion is, of course, George. Standing opposite George is heaven’s champion, Death, who Mary initially personifies as a conqu’ror (conqueror) who asserts his right over her dying soul. While the tone of this description is quite ominous, what follows is a depiction of Death as far from the frightening image of the Grim Reaper as you’re likely to read! Death’s appearance is distinctly untyrannical: he’s chearful and not one terror clouds his meagre face. Meagre actually means ‘thin’ or ‘lacking’ and sometimes has connotations of weakness. It’s certainly an unexpected description and merits a moment’s thought. Perhaps Mary means meagre only in comparison with George, or that his face is in some way obscured? After all, he’s a part of the heavenly or incorporeal realm and is normally hidden from mortal perception. Whatever the ambiguity of his appearance, his intention here is to relieve Mary’s suffering on earth and transport her to heaven; He promises a lasting rest from pain; And shews that all life’s fleeting joys are vain. Moments like this resemble a Jisei poem ruminating on death and accepting the brevity of life; fleeting means that something is here and then quickly gone.

Perhaps because his inevitable victory is assured, Death doesn’t act like a typical conqueror either. Through personification, he is imagined not as a state of being or unbeing, but as a guide between life and after-life. Verbs describe actions, and through actions a person’s character can be truly judged. Make a list of actions ascribed to Death and you’ll find: promises, shews (an archaic spelling of ‘shows’) veils, sets, tells, asserts, wooes. He may be a conqueror, but he’s a curiously polite, gentle and benign one, seeming to care about Mary almost as much as George does. Only the word assert (and maybe tells) connotes any strength, reminding us that death is an implacable and inevitable force. Instead, he is gentle, tender and even kind. Surprisingly then, a comparison between Death and George reveals more similarities than differences. She addresses both using apostrophe, encouraging us to see them as rival suitors. Where George is her husband and best of friends, Death is trying to romance her away. Where one is tender the other is… well, also quite tender! Death doesn’t ‘take’ or ‘kill’ Mary – he wooes her, a romantic word that implies a formal seduction and creates the impression that Death can wait patiently until she decides the time is right. It’s in this word that the competition between the rival suitors might rage most fiercely, and it won’t be resolved until the final line where Mary admits that in her heart and soul she will always remain George’s faithful wife.

Throughout the poem, the ‘process’ of death is curiously gentle; death’s first action is to veil me from thy sight; as a euphemism for dying (euphemisms are metaphors that soften the harsh edges of unpleasant ideas, like dying) the action of being draped with a veil is gentle and respectful. In fact, the words ‘death’ and ‘die’ only appear once each in the poem, and one of those moments is in the final line (outside of the title, anyway, which would certainly have been added later; Verses Written on Her Death-Bed at Bath wasn’t published until 1735, twenty years after Mary succumbed to her sickness). On several more occasions, Monck employs metaphors for dying, all of which are euphemistic: parting hour; journey to the skies; sorrow’s end; lasting rest; shake off life. Almost uniformly, these phrases are couched in soft language, when spoken aloud the longer vowel sounds (assonance) are most audible, such as O, OU and OW, or soft alliterations like sibilance (skies, sorrows, lasting rest, shake) and whispery fricatives: shake off life. The effect is both touching and admirable, as we see Mary contemplating her own death quietly and fearlessly; after such an extended illness, we see her calmly preparing for the end of her life.

Nevertheless… something is preventing Mary from willingly departing with Death. He may be only one man, but George still has a powerful weapon on his side: love. Just as Death was personified as the champion of heaven, now Love is personified as an earthly emotion with the power to oppose Death. Despite the alluring promise of a release from pain, Mary admits that love, fond love, would yet resist [Death’s] pow’r and Would fain awhile defer the parting hour. In these lines, defer (meaning ‘delay’) obstruct and resist imply the possibility of love combating Death; even if love cannot win, perhaps it might buy Mary more time? And Love seems to revel in thwarting death’s desires for as long as he can: fain means ‘gladly’ or ‘with pleasure’. No matter how hard her sickness has become to bear, Mary’s desire to remain with George is as seductive as any heavenly temptation.

We haven’t discussed elements of form at length yet, but I’m sure you’ve already noticed that Mary writes in rhyming couplets – each pair of lines ends with words that sound like each other: employ / joy; friends / send; right / sight and so on. Rhyming couplets have the power of suggesting a strong connection between two things, in this case Mary and her husband. Additionally, every one of the rhymes in the poem is a full rhyme, meaning both the consonant and vowel sounds in each pair of words resemble each other. The strength of the rhyming sounds mirrors the bond between Mary and George in a way that is touching and even reassuring, especially when the poem hints that perhaps love is strong enough to survive not only their physical separation on Earth (in 1715 there were no convenient trains to whisk them the hundred miles between London and Bath) but being parted by death as well. Another aspect of form is rhythm. Mary writes in iambic pentameter, by which each line consists of five pairs of syllables, each pair (technically called a foot) arranged weak-strong, or unstressed-stressed. Listen to the rhythm of a line or two being read out loud and you should hear the de-dum, de-dum, de-dum of your heartbeat pulsing steadily underneath the words; perhaps this association is why iambic measures are traditionally used when writing love poetry.

Mary, then, finds herself in quite a pickle. She longs to be released from suffering, but she imagines George’s mourning image and knows that her death will cause him untold grief. It’s this knowledge that obstructs her journey to the skies. Mary was suffering from consumption, a wasting sickness we now call tuberculosis. She calls life a painful pilgrimage, another metaphor implying that simply existing day to day is long and arduous; the word pilgrimage has connotations of duty, obligation and sacrifice. Is Mary implying that she endures and struggles against a debilitating sickness only out of a sense of obligation to her husband? She embellishes the metaphor with plosive alliteration. Formed by expelling air from between closed lips, plosive P is good at representing negative feelings, in this case the pain Mary must be feeling as tuberculosis ravages her body. In fact, throughout the poem you’ll find diction describing life on earth as ‘painful’ contrasting with words describing death as pleasurable: for example, compare fleeting joys with eternal scenes of heav’n, painful pilgrimage with rest and negative emotions such as mourning to the celebratory word rejoice. The only exception to this is the warmth and pleasure with which Mary remembers George. Remember pleasing source of earthly joys? Analyse this line to find warm assonance (long EA and O sounds) and soft sibilance (pleasing source), as if simply remembering her life with George is a balm that soothes the pain of life on earth.

To escape this conundrum, Mary changes tack and begins to address George more firmly. She asks him: should’st thou grieve to see my sorrows end? Should’st thou grieve that rest is come at last? Repetition plays a large part in creating the impact of these lines. Should is a modal verb that transmits a degree of strong emotion, and Mary repeats this word twice (don’t forget that repetition at the beginning of lines of poetry is technically called anaphora: Should’st thou grieve is a great example of this technique put to good use). Repeating grieve is a clear acknowledgement that she sympathises with George’s upset; but, by framing these lines as rhetorical questions, she is really asking him to understand that, for her, life has become unbearable. Consumption was a terrible illness, her body is unable to endure any longer, and she would willingly be rid of her sorrows. Mary calls George unwearied and, though I’m not sure if you’ll agree, I sense a small thorn hidden in this rosy compliment, a reminder that he remains in the blush of health and may not quite be able to understand what she’s going through. The jab – if any – is softened by, again, repetition of friend, a reminder of all the time they have spent together.

While presented in one unbroken stanza, reading carefully to punctuation should allow you to split the poem into quatrains (groups of four lines). Scroll back to the top and you’ll see full stops marking these unofficial ‘stanzas’. Reading this way creates a poem of five quatrains in which Mary’s dilemma is presented, followed by a single couplet that resolves her internal conflict. In this regard, Mary follows the poetic tradition of the turn, by which a poem ‘shifts’ at the end to present a new idea or new angle on the topic. Having established a complex web of oppositions in the first twenty lines – life vs death, the mortal world vs eternal heaven, pain vs joy and, of course, the choice between her husband, who she loves, and death, who she longs for – Mary masterfully resolves all these contradictions in the last couplet.

Firmly, she instructs George to rejoice to see me shake off life. Knowing he might be reluctant to accept her death, she speaks in the imperative tense, placing the verb (rejoice) close to the start of the line. Also called the command tense, on reading this letter George would have been in no doubt that his wife’s final wish was to have him celebrate her death rather than mourn or grieve. The euphemism to shake off life is also an active metaphor; the words are curiously lively, as if dying is not the end but a continuation of life, like a snake shedding its skin or a tree shaking off its leaves. Mary’s insistence is emphasised by deliberate alliteration (Rather rejoice) that gives weight to her instruction. It might seem a little counter-intuitive, but perhaps you’ve had a conversation with an older relative who expressed similar thoughts. My grandmother used to hope that when it was her time to go, we’d celebrate her life and throw a party rather than dwell sadly over her death. In its own way, this sentiment chimes with those Buddhist-inspired Jisei poets, who accepted the inevitability of death and spent their final moments in rumination rather than recrimination. In the last line, Mary brings together the oppositions of life and death, speaking the word die without euphemism and in the same breath as lived, once again as if death is not the end but simply a continuation of life in another form.

I’d like to think that Mary’s beautiful letter was a comfort to George at a difficult time, and that he realised that her suffering was eased not only by Death, but by the memories of their long and happy life together. In the end, dying is an inescapable part of life. But in this case, while Death might have succeeded in conquering her body, her heart will forever belong to George.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Because I Could Not Stop For Death by Emily Dickinson

In this poem too, Death is a gentleman come to politely escort Dickinson’s speaker away from life. He arrives in a horse and carriage and rides her through the town and out into a land that seems to fade away before her eyes.

- Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Like Monck, John Keats was suffering from consumption (a disease we now call tuberculosis) when he composed his famous Ode sequence in 1819. In this poem, he contemplates an urn on display in the British museum – the images on the urn transport him to a time and place free from the ravages of his illness. In another point of comparison, there are several famous examples of apostrophe for you to pick out as well.

- The Moment When Shiki Breathed His Last by Masaoka Shiki

One of three poems written by Shiki in the hours before his death, this is a beautiful example of the Jisei poetic tradition. Visit this page to read the poem and the story of Shiki’s deterioration, his knowledge that his time was coming to an end.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Verses Written on her Death-Bed at Bath at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on exploring the poet’s use of figurative language, including euphemism and metaphor.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Mary Monck’s poem? What do you imagine was George’s reaction on receiving this letter? Have you ever heard of Jisei death poems? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Great post and some phenomenal illustrations! Well done Natalie!

Amazing illustrations and as always a great analysis. Well done Natalie, Doug and Alissa

you can talk about how the caesura in the last line not only slows down the poem but also the steady slowing down of her heart during her final moments

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, but bears it out even to the edge of doom

My spellbound heart has made and remade the necklace of songs, That you take as a gift, wear round your neck in your many forms, In life after life, in age after age, forever