Sink or swim in the sea of Robert Lowell’s obsession.

“Grand, intimate, eccentric, funny, disturbing -“

Max Liu, writing in 2017 (to mark what would have been Lowell’s 100th birthday).

Night Sweat was first published in Robert Lowell’s 1964 collection For the Union Dead; by this time Lowell was already famous as a confessional poet, something new in American literature. Confessional poems reveal the intimate thoughts and feelings of the writer; because we are being directly spoken to, as a person might whisper confessions to a priest, the reader has the impression of being invited into the poet’s confidence as they admit to anxiety, fear, guilt or some other secret wrongdoing. Confessional poems use ‘images that reflect intense psychological experiences,’ as we’ll see in today’s poem. In Night Sweat, Lowell confesses his obsession with his own writing. He aspires to create one writing; a poem, collection, or body of work that will define him as an artist. To achieve his goal, he needs to overcome some kind of block – his own doubts and anxieties, perhaps – that’s inhibiting his creative potential. But getting ‘in the zone’ is not always easy; the feeling of freedom comes upon him only at night, when he enters an altered state of being, a mysterious condition that brings clarity – but vanishes each morning leaving him physically and emotionally exhausted. Therefore, Night Sweat is an ars poetica, a poem about the writing of poems – but it’s also a study of obsession, and the cost that one must pay to realise an artistic vision. Lowell suggests that mastery of his craft necessitates detaching himself from the real world and diving so deeply into his work that he might not be able to come back up. He fears that, for his greatest work to be ‘born’, he himself might have to die:

Work-table, litter, books and standing lamp, plain things, my stalled equipment, the old broom – but I am living in a tidied room, for ten nights now I’ve felt the creeping damp float over my pyjamas’ wilted white… Sweet salt embalms me and my head is wet, everything streams and tells me this is right; my life’s fever is soaking in night sweat – one life, one writing! But the downward glide and bias of existing wrings us dry – always inside me is the child who died, always inside me is his will to die – one universe, one body… in this urn the animal night sweats of the spirit burn. Behind me! You! Again I feel the light lighten my leaded eyelids, while the gray skulled horses whinny for the soot of night. I dabble in the dapple of the day, a heap of wet clothes, seamy, shivering, I see my flesh and bedding washed with light my child exploding into dynamite, my wife… your lightness alters everything, and tears the black web from the spider’s sack, as your heart hops and flutters like a hare. Poor turtle, tortoise, if I cannot clear the surface of these troubled waters here, absolve me, help me, Dear Heart, as you bear this world’s dead weight and cycle on your back.

The poem begins innocuously enough. As a confessional poem, for once we can say the speaker is Robert Lowell himself. He’s in his study, sitting at his work-table surrounded by the litter of his work: I imagine assorted pens, paper, maybe a typewriter, scrunched up notes tossed aside. This is his creative space – but he’s struggling for ideas, represented by stalled equipment (maybe his typewriter – or his brain – is stuck), plain things (referring to the simple implements of a writer’s craft; but plain implies the blankness of white paper) and a standing lamp that’s not going anywhere. He’s living in a tidied room; it’s neat, but a bit too neat, mundane and ordinary. The first two or three lines are halting and timid, broken up with frequent caesura, as if his thoughts are fragmented and incomplete: Work-table, litter, books and standing lamp, plain things, my stalled equipment, the old broom – So far the poem is no more than a list of stationary objects lacking in action (notice how there are no verbs). Lowell seems to be suffering from a kind of ‘writer’s block’ – he can’t find the right words, is stuck for ideas, or too anxious to write unselfconsciously.

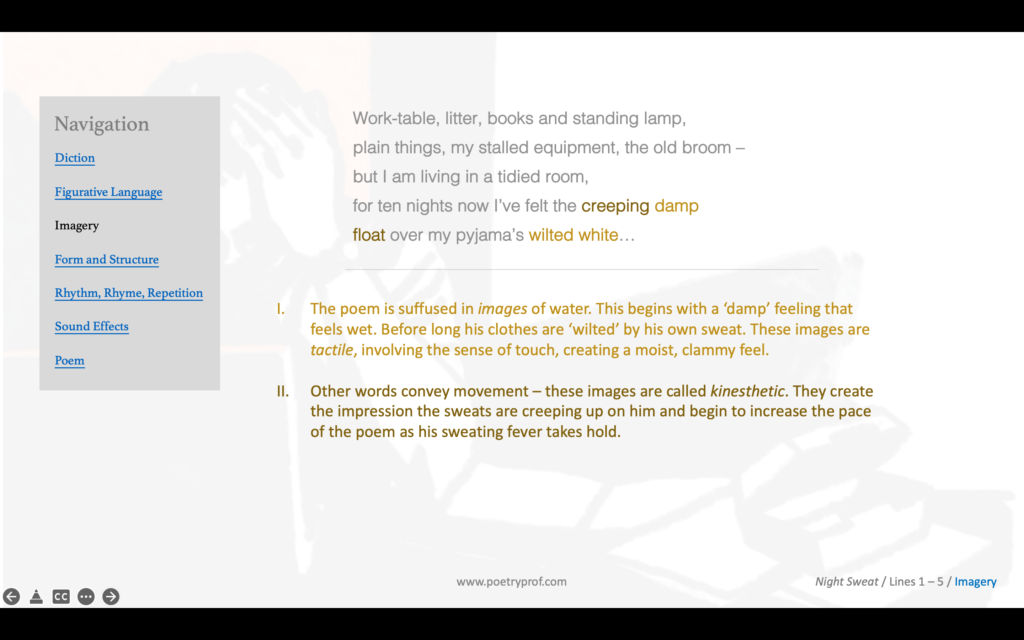

It turns out that inspiration needs not so much a physical space as a necessary time: the forces that move him come out at night. So he’s waiting – with a mixture of trepidation and eagerness, like an addict about to indulge in his next hit – waiting for darkness to fall. Once night surrounds him, he is gripped by the prickle of a feverish sweat creeping up on him from out of nowhere. Droplets bead his skin, wilting his starched white pajamas (that plain, empty colour again) and he feels a floating sensation, as if his writer’s brain untethers itself from whatever was weighing it down and starts to whirl. Whatever this condition is – a dream, a panic attack, a bout of madness – it has a profound effect on both his body and mind: as the night sweat seizes him, the poem becomes suddenly active. Several words that suggest movement (creeping, float and wilting) are used in quick succession. His poetry gathers pace and energy, creating the impression that he’s been somehow unblocked or unclogged. Whereas the opening couple of lines were halting, now they flow one into the next using enjambment (I’ve felt the creeping damp float over my pyjamas runs over a line break without pause). The rhythm of the lines also begins to resolve itself: the first lines are difficult to scan and irregular in beat; but when he’s in the midst of his sweating fit, when everything streams… the lines flow in perfect iambic pentameter.

Where the sweat comes from remains ambiguous. It seems psychosomatic, a physical representation of his anxiety. Throughout his life, Lowell suffered bouts of depression and even panic attacks, and he often doubted his own abilities as a writer. But it’s a little too simplistic to say his night sweats are a straightforward symbol of fear. When gripped by this mysterious condition, he actually feels clarity and conviction: everything streams and tells me this is right. He describes his sweat as sweet and soaking in night sweat is akin to being in a state of ‘flow,’ where creative thoughts and inspiration seem unbounded. After a time, the salt in the sweat forms a crust on his skin, sealing him up inside a chrysalis-like cocoon – it’s here that it feels like his ambition to create, to really write, is almost within touching distance. He refers to one writing which he’s obsessed with creating, whether a poem, book, or style of writing that he’s trying to master and will define his identity as a writer. The obsession with the number one is signalled through repetition of this word: one life, one writing… one universe, one body… Randall Jarrall, a fellow poet and close friend, wrote that Lowell ‘understands the world as a sort of conflict of opposites’ and this poem could stand as a case in point. In his quest for writing-perfection, Lowell seems to be trying to reconcile all kinds of oppositions (night and day, light and dark, black and white, wet and dry, burning and drowning, movement and stillness, up and down, life and death, husband and wife) into one. But he lacks any sense of balance and he’s moving further and further towards an extreme state. For example, he describes life as a downward glide and feels like existing wrings us dry, a phrase conveying a sense of exhaustion with the world, and betraying the fear that his ‘well of creativity’ will dry out at the same time. Eagle-eyed readers will already have spotted that the poem is twenty-eight lines long and is marked with its first full stop at exactly the halfway point. This duality of form throws light on the contradictions inherent in Lowell’s obsession and embodies the paradox of trying to fit two into one all the time: written in one long unbroken verse, his poem is actually made of two sonnets stitched together.

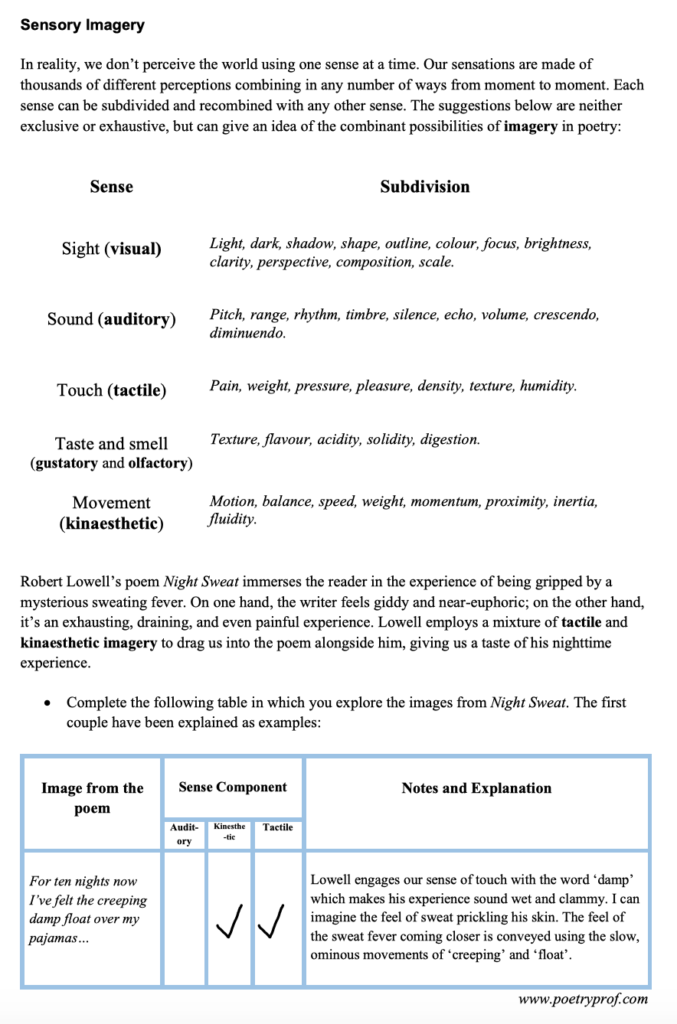

Therefore, his uncontrolled night sweat (alongside other watery images in the poem) symbolises the double-edged nature of obsession, of being immersed in one’s passion to the detriment of one’s mental and physical health: creeping damp, pajamas wilted white, my head is wet, everything streams, soaking in night sweat, wrings us dry all submerge Lowell in his obsession. The pace and energy of the poem drags us along, helped by words such as streams and downward that involve movement (images like this are kinaesthetic) pulling us down into the night sweat fever alongside the writer. Perversely, the sensation is quite giddy, almost euphoric. Many lines are suffused in assonance, especially long I and EE sounds that convey giddiness: creeping, white, sweet, me, my, everything streams, right, fever, night and on more than one occasion, Lowell uses liquid alliteration: wilting white, light lightens my leaden eyelids. Made with the letters L, R and W, liquid sounds work in combination with copious sibilance (sweet salt embalms me, soaking in night sweat, seamy, shivering, flesh, washed) to thicken the impression of everything being doused in water. Rhymes blend words together so that, for example, glide/dry/died/die are barely distinguishable. Reading the first half of the poem is something of a rush – but it’s also draining him or burning him up. Sweat comes from inside a person, like a kind of elemental life force, and it’s not inexhaustible. There’s also a sense, evoked by the thick tactile images, images that we can feel oozing from the page, that he’s becoming submerged in his obsession. Lowell is desperately treading water; his condition brings a kind of hyper-clarity, but he’s in real danger of drowning. At the end of the poem, he admits to this fear and worries that he cannot clear the surface of these troubled waters.

The idea that his writing obsession involves self-sacrifice keeps bobbing to the surface of the poem. Life’s fever and the animal night sweat of the spirit burn are both images communicating the pain of obsession and suggesting his own life energy is being consumed by his ambition. The word animal implies that his driving force is deep, instinctive, and powerful; he understands it’s not logical, but is powerless to resist when the impulse to create is so strong. When his sweat dries on his skin, he uses the word embalms, meaning ‘to preserve a corpse from decay’ and he feels like he’s burning up inside a sacrificial urn. Other uses of diction also hover around the idea of dying, skulled, soot, dead wood, so death never seems too far away. On more than one occasion, he writes about the feeling of having experienced death before (always inside me is the child who died) and having to carry that feeling with him like a burden that can’t be shed. The identity of the child inside him is ambiguous and open to interpretation: I like the idea that this child is his unwritten work. When he admits that always inside me is his will to die it’s feels like he’s fighting against himself. The phrase always inside me… is repeated at the beginning of two lines (a type of repetition called anaphora) making the child a key part of his obsession; a symbol of creativity, but one suffused in doubt and anxiety. His work is an unborn child that may never be nursed successfully to life. Even after ten nights, there’s no sign of Lowell’s self-destructive, self-sacrificial ritual stopping. Quite the opposite: I have the sneaking suspicion that he’s sinking ever deeper into his obsession.

As morning breaks, his sweating fit evaporates and so too does his manic, creative power. If night is the time of maximum flow when it feels like he’s in tune with the universe, the day is more of a struggle. The transition from night to day (and from the first to the second half of the poem) is marked by a strange, ambiguous cry, seemingly directed straight at the reader: Behind me! You! It’s a bizarre, jarring moment and the short, sharp exclamations, almost onomatopoeic in their tone and brevity, makes it feel like he’s starting awake out of a terrible dream. Because he hasn’t slept properly, by day he’s exhausted, a feeling expressed through diction suggesting weakness, like shivering and leaden; he’s so tired his eyelids feel too heavy to lift. As he lies in bed trying to recuperate, he mentions his wet clothes discarded in a heap and describes them with the clever word: seamy. On one hand this simply tells us the ‘seams’ of his clothes are showing, they must have gotten turned inside out as he peeled them off his sweat-soaked body. But seamy has connotations of immoral and unpleasant behaviour too – the phrase ‘seamy side of night’ suggests all the illicit activities and sordid scandals that happen after dark. The confessional style of poetry really comes into its own here, as it feels like he’s letting us in to his secret. The wet clothes are a locus for his guilt, like evidence left at a crime scene. The idea of his behaviour being somewhat sinful is also evoked through the image of my flesh and bedding washed by light; the action of ‘washing’ has religious connotations and implies being cleansed of sin as well as sweat and grime. The light is overwhelming, in his shattered and exhausted state he simply can’t cope with the penetrating daylight: on the instant his flesh is touched with daylight, he sees my child exploding in dynamite. This is a sudden and shocking moment which fuels the idea that the mysterious child who keeps cropping up in the poem is his embryonic writing, still unborn and too weak to survive exposure to the light of day. Light is placed in opposition to night’s darkness, which seems more and more like a refuge that he wants to return to, despite his residual guilt.

It’s not that he can’t create at all by day. There are patches of darkness and shadow even in daylight (the word dapple means ‘to mark with dark spots’) and dabble in the dapple of the day suggests he’s doing some scribbling in a shady room somewhere. Ironically, this line is one of the most perfectly formed in the poem, presented in flawless iambic pentameter and embellished with a beautiful combination of alliteration, assonance and internal half-rhyme (dabble/dapple… day). Briefly, we see the potential of the speaker to realise his writing ambitions – if only he can conquer the demons of his own mind and find the balance that always eludes him. But, let’s not get ahead of ourselves; dabble means to try something casually or ‘superficially’ and he’s not going to write his masterpiece by ‘dabbling.’ For that, he’s got to immerse himself in his work, climb deep down into his sacrificial urn again. The night-time fever is like an addictive drug – he craves it even as he knows it is destroying him. So throughout the day he’s distracted by his own mind, symbolised by the sound of horses that whinny constantly. Part of him is eager for night to fall so he can return to that hypnotic, trancelike time (the soot of night) where everything streams.

The exception to all of this is his wife. Her entrance is marked by lineation (my wife… is placed at the head of the line) and caesura (created by an ellipsis when she comes in to his study…) as if her simple presence calms the constant spinning of his brain, quietens the drumming hooves of those gray skulled horses. His wife represents balance, something he totally lacks. When she enters the poem, she brings a special lightness with her, counteracting his leaden heaviness, momentarily at least. Where he feels life as a downward glide, she goes in the opposite direction: the simile your heart hops and flutters like a hare creates a visual image of her exerting an important ‘upwards’ force on everything around her. Even the sounds of the lines in which his wife appears are some of the lightest in the poem: your heart hops… like a hare features aspirant alliteration; made with the letter H, aspirant is one of the softer, lighter consonant sounds. Too, this line is written almost entirely in monosyllables so each word (except flutters, which itself connotes her being light as a feather) has only one syllable. In another line he says your lightness… tears the black web from the spider’s sack, where the sack is like a repository for negative thoughts, fear and pressure. The balancing power of his wife, her lightness, counters the blackness of the spider’s web from which she metaphorically disentangles him. The way her ‘upwards’ force counteracts his downward spiral is implied through the rhyme scheme at the end of the poem as well, which follows a back-to-front pattern called chiasmus: ABCCBA – the rhymes seem to be heading in one direction, before reversing and coming back up the other way.

Considering how introspective the poem has been, it ends in a way that’s surprisingly sympathetic when Lowell admits the cost of his obsession/ambition is paid not only by himself, but by the person closest to him. A poem that’s been all about me (I lost count of the number of times I, me and my are repeated in the poem) suddenly ends with you and your. This switch of perspective, away from the conventional confessional focus on ‘I’ and onto another person instead, represents the turn that a reader might expect at the end of a traditional sonnet (the turn, also called volta, is the moment where something alters, the tone shifts, or the perspective on the subject matter is changed: my wife… your lightness… is the moment where Night Sweat turns). He portrays his wife as ‘light,’ but not ‘lightweight.’ Emotionally, she’s the tough one, strong enough to bear the weight of the world on her back. That Lowell needs her support, and regrets the price he makes her pay, is revealed through his naming her Poor turtle, tortoise. This instance of directly addressing somebody who’s absent is technically called apostrophe (although you can remember his renaming of her as a straightforward metaphor as well) and, used here, it creates an allusion to the World’s Turtle. A myth common to many cultures, including Native American, this turtle exists at the centre of creation, holding up the world on her hard-shelled back. At the end of the poem, he acknowledges that any burden he places upon himself he places on her as well, describing himself as a dead weight that tugs them both downwards. He explicitly asks her to forgive him and to support him when he pleads, absolve me… help me, his desperation expressed through this pair of imperatives placed one after the other. Still, when night falls, he can’t – or doesn’t want to – prevent the sweat creeping up on him again, despite knowing that in sacrificing himself, he sacrifices his wife as well.

Lowell was not wrong; only a couple of years after this poem was written, he would separate from Elizabeth Hardwick, his wife of 23 years, and move to England – although he would return to his Dear Heart at the very end of his life. Robert Lowell died in 1977, leaving behind him an incredible legacy. He was part of the transformation of the landscape of American poetry. He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for his poetry and is now mentioned in the same breath as literary titans Allen Ginsberg, Sylvia Plath and his friend and correspondent Elizabeth Bishop. While he never overcame his personal demons, some might say he managed to find his one writing nevertheless.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Epilogue by Robert Lowell

Another confessional poem in which Lowell confides in us his doubts about his writing. He wants to ‘write something imagined, not recalled’, but feels ‘paralysed’, situations he writes about in Night Sweat as well.

- Nearing Forty by Derek Walcott

As he approaches middle age, Walcott worries that his writing has not achieved the stylistic clarity of his mentor, to whom this poem is dedicated. Lying awake at night, he draws inspiration from the sound of rain on the rooftop. This is another challenging, but rewarding ars poetica: a poem about the craft of writing.

- The Ambition Bird by Anne Sexton

Another seminal figure in American confessional poetry, Anne Sexton, suffering insomnia, lies awake at 3am feeling dark wings flopping in her heart. She calls this bird Ambition – he wants to be dropped from a great height, to bolt for the sun and be immolated. Anne asks, ‘why can’t i just drink cocoa?’

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying Night Sweat at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model analytical essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining imagery in this poem.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Robert Lowell’s poem? Where do you think the night sweat fever comes from? Who is the child inside him? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below.