Stevie Smith asks if we couldn’t all do a little more to help from time to time.

‘A purposeful and substantial talent’

Times Literary Supplement

In today’s poem we’re going to hear a voice from beyond the grave, the voice of a man who swam out of his depth and couldn’t get back, telling us that he was not waving but drowning. Through this simple repeated line, the poem suggests his death was not inevitable. It could have been prevented if the onlookers, those unlucky enough to be there when the tragedy unfolded, had understood his desperate appeals. Of course, they had nothing to do with it – he swam out too far and got into difficulty. How was anybody to know he needed help? And even if they did, they probably couldn’t have done anything anyway – could they?

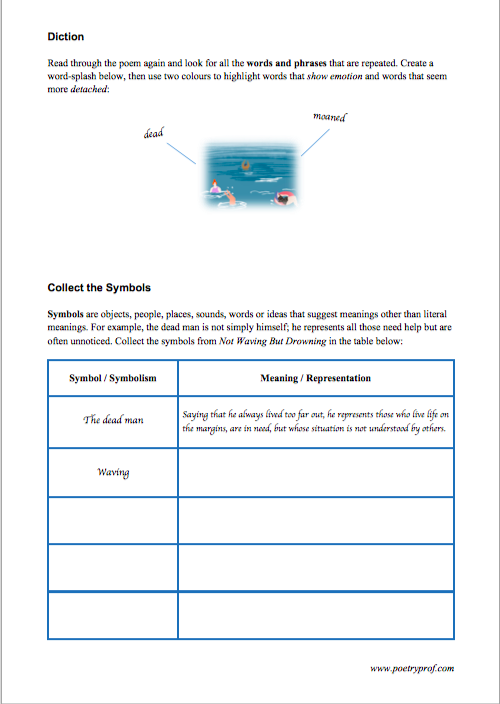

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.

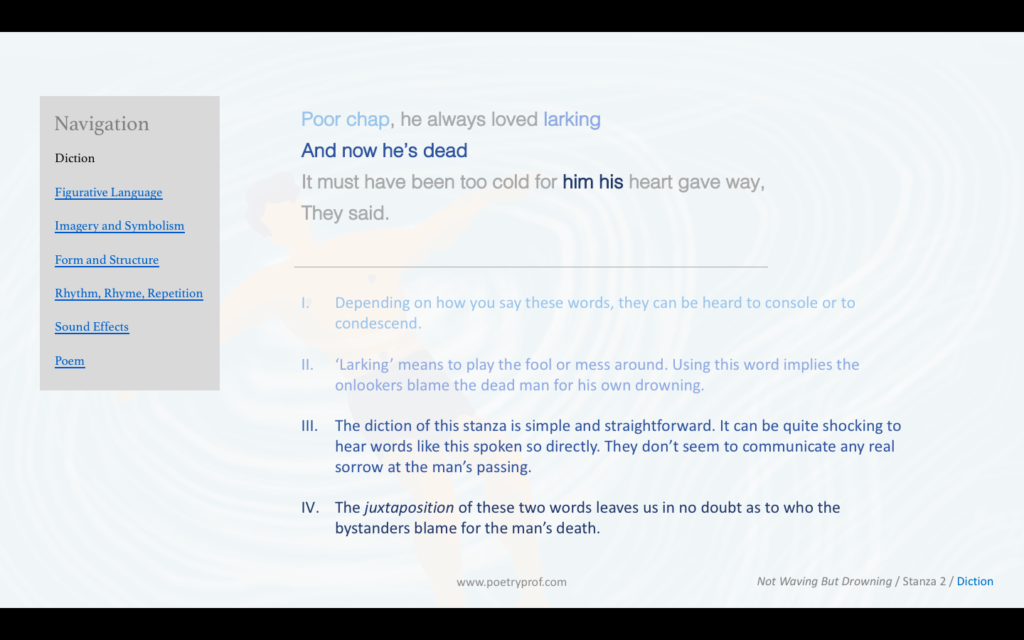

Poor chap, he always loved larking

And now he’s dead

It must have been too cold for him his heart gave way,

They said.

Oh, no no no, it was too cold always

(Still the dead one lay moaning)

I was much too far out all my life

And not waving but drowning.

I always imagine the events of this poem to be played out on the sands of an imaginary beach, lined with tourists, not one of whom came to the drowning man’s aid because they all thought he was larking around – a word that means ‘playing the fool.’ They misinterpret his desperate flailing as waving to some unseen friend on shore. But, of course, there is no beach, and the man had no friends. The refrain not waving but drowning (including the title, this line repeats three times) is a conceit (a kind of extended metaphor that contains the central idea of a poem) encapsulating Smith’s belief that people’s capacity for empathy and understanding has diminished in the world around her. Each person is closed off to every other; our lives intersect but never really intertwine. We live in a world of bystanders. In this world we may not know our next-door neighbour’s name, or where the new family at the end of the road has come from. We may sit next to the same person on the bus each morning but never find out anything about them. We never realise that our colleague’s heart has been broken or see past our boss’ suit to the living person underneath. Worse, in this world tragedies play out under our very noses, but we are indifferent to the suffering of others.

So in Smith’s poem, a man drowns in plain sight because other people didn’t come to help. The opposition between him and the others is set up in the third line when he says: I was much further out than you thought. Perhaps his frantic waving was genuinely misinterpreted. Or perhaps it’s easier to believe that people who need help don’t really need help – they are just playing whatever system it is they happen to be stuck in. He’s not crying out for help, he’s just attention-seeking. She’s not struggling to understand, she’s just playing around and taking us all for fools. He’s not poor, he’s a scrounger. She’s not lonely, she’s just a weirdo. He’s not drowning, he’s waving.

It may take a couple of readings to realise we hear not one, or two, but three voices in the poem, one of whom is the voice of the man just drowned. We also hear the speaker, who begins the poem and the voice of observers on the ‘beach’ upon which the dead man’s body washes up. Smith interweaves these three perspectives, each of whom speaks in a different type of poetic voice (out of the four generally available): invented, public and invisible. She keeps her own voice (the personal voice is employed when the poet wants us to hear her own voice as clearly as possible) out of the scene.

The first voice we hear is an example of an invisible voice. This kind of speaker is akin to a narrator in a story; the reader doesn’t really notice this voice at all. Very little of the speaker’s character intrudes into the poem. Sometimes, this voice is taken for the voice of the poet, but it would be a mistake to think that here. The invisible voice is detached in a way Stevie Smith is not. Despite the invisible narrator only delivering three or so lines in the whole poem (the first two lines, They said, and the line in brackets in stanza three), because this is the first voice we hear it sets the tone for the poem:

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

Consider for a moment the information that these lines convey: a man has died by drowning. He died in full view of others who could have helped him but they didn’t realise the difficulty he was in. Nobody heard him or can hear him now (except for our invisible speaker) but he’s moaning, a word suggesting he’s in pain or in need. The content of these lines should be quite shocking, but our narrator relays all this information calmly, without emotion, in a detached tone of voice.

This attitude is even more pronounced when the voice of people present at the scene of the man’s drowning is reported. These people speak in one voice, presenting the views of a group or majority, so this type of voice is called the public voice. On the surface, these people seem to offer consolatory words: Poor chap. But they seem deaf to the ghostly voice telling them I was much further out than you thought and not waving but drowning. There’s an accusatory you tucked away in this line which, if not squarely laying the blame on those standing by doing nothing, implies that they are in some way involved.

The public voice observers wouldn’t agree, and you can see from the platitudes they automatically roll out that they consider the man’s death to be nobody’s fault but his own. Their words acknowledge the tragedy, but go no further:

Poor chap, he always loved larking

And now he’s dead

On the surface, this line expresses sympathy and condolence, but listen to it in your mind’s ear and you’ll hear it delivered with a shrug: what it really says is ‘it was his own fault, you can’t blame us.’ A note of condescension underpins poor chap and you can see the finger of blame pointing to the dead man when the observers say: he always loved larking around. Most of the work here is being done by the little word larking, with connotations of carelessness and stupidity, an impression heightened by alliteration (loved larking) which sounds more light-hearted than serious. The abruptness of the second line, And now he’s dead, is quite shocking more because of the callous way in which the verdict is pronounced. Most people, in these situations, might try to soften the blow a little – but these observers say the word dead right out. It’s the use of this word that aligns the invisible speaker who began the poem with the public voice observers: she too is not averse to calling a spade a spade and repeats the word dead precisely once in each verse.

After this abrupt proclamation, the observers waste no time in casting around for the cause of death, quickly settling on heart failure caused by cold. Look at the degree of certainty loaded onto the phrase It must have been too cold for him by that little modal verb must. It’s as if the speakers are trying to persuade any onlookers (like you and me, dear reader), as well as each other, that his death was an accident for which nobody – least of all themselves – can be blamed. Except the dead man himself, of course. Ironically, these public voice speakers unwittingly stumble upon the right cause of death, though not in the way they intended: cold suggests the detached and uncaring attitude of the people around the dying man, and perhaps extends to the circumstances of his lonely life, rather than the literal cold of the water. The words him and his are squeezed together in the third line, deepening the impression that the observers are trying to distance themselves from the event, loading all responsibility onto the dead man and his own weak heart, another suggestion that he lacked the strength needed to cope with life. You may also have noticed all that aspirant alliteration. Made with the letter H, aspirant creates a weak sound which you might associate with breathing, but also represents the weakness the onlookers ascribe to the drowned man, as if he wasn’t tough enough to look after himself. Briefly, then, the poem returns to the invisible voice speaker, reporting in her detached way that this is all They said. Case closed.

Except the story is not over. Smith gives almost the whole of the final stanza to the voice of the drowned man, and his first few words encapsulate everything she is trying to convey in her poem:

Oh, no no no, it was too cold always

A poet uses the invented voice when she creates a character (also called a persona) in order to deliver a message, and that’s exactly what happens here. Having heard the rushed excuses of the onlookers, he strongly rejects their judgement – although he does not disagree that it was cold that killed him. It is through the repetition of cold and the use of the word always that we come to recognise the layers of meaning in this word; that it was the coldness of the world and its people that allowed the man to die. In contrast with the detached tone of voice we have heard from the others, the dead man lets all his emotions out in an onomatopoeic Oh, and the repetition of no no no. This time assonant sounds (Oh, no no no it was too cold always) deepen the voice and gives this single line an emotional resonance totally lacking in the response of the observers.

The poem ends where it began, with the dead man insisting he was not waving but drowning. This structure is called loop composition and, used here, it suggests nobody has learned anything and nothing has changed. The observers are entrenched in their position, insisting the man only had himself to blame. But by now, we should recognise the dead man as symbolic of others in need. His moaning is their moaning, his desperate waving their own cries for help. People are still drowning, but nobody recognises the signs. It’s hard to decide where the invisible speaker sits: is she on the side of the dead man or a part of the indifferent masses? In her favour, she seems to be the only one who can hear his silent appeal and continues to report his words when others would rather move on. But weighing against her, her voice remains detached and she never gives any hint that she may feel an emotional connection with the man. The final interjection from our narrator (Still the dead man was moaning) repeats the word still, which doesn’t help much either – is she faithfully reporting the facts, or does the word betray a little irritation? Consider the grammatical function of brackets too – they can be used to add less important information into a sentence, as if the dead man is now no more than a sideshow in his own story.

Smith’s poem seems quite slight, which is characteristic of much of her poetry and perhaps why she didn’t always get the credit she deserved as a ‘serious’ poet during her lifetime. Not Waving But Drowning is presented in simple rhyme, a sing-song rhythm playing out through most of it, and a limited, repetitive diction (apart from the obvious refrain, words like always, still, lay, cold and far or further out are quietly repeated). On the surface the story it tells seems quite simple too; but the thoughts it provokes are disturbing. The form of the poem fits Smith’s message perfectly. For example, most of the lines end in an unstressed syllable, like this:

/Nōbody /hēard him, the /dēad man,

(But) /stīll he lay /mōaning:

This is technically known as falling rhythm and accompanies the image of a man gradually slipping under the surface perfectly. More generally, the simple form challenges your preconceptions. Are you like one of those bystanders, who prefer a quick and easy explanation? If so, read the poem simplistically and shrug, ‘so what?’ Or do you want to dig a little below the surface? If you do, you’ll discover potent irony. Through displaying apathetic voices without personal comment, Smith allows you to find your own outrage: that this callous indifference is the default position of so many when confronted with the misfortune of the few.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- Alone in the Woods by Stevie Smith

You can probably guess from the title what this poem has in common with Not Waving But Drowning. This poem is a lot darker and a lot denser though. The speaker isn’t just ignored – you can feel the hostility and danger emanating from every line of this deceptively simple rhyme.

- Life Is Fine by Langston Hughes

In this poem, the speaker goes to extraordinary lengths to be seen and heard – jumping into a river, climbing to the top of a building and threatening to jump off. But does anybody really notice?

- First They Came For… by Pastor Martin Niemoller.

Smith’s poem reminds me of nothing less than this famous verse written in the aftermath of World War Two. The quintessential ‘bystander’ poem.

- The Partial Explanation by Charles Simic

Sitting at a table in a restaurant by himself, the speaker’s only companion is a glass of ice water. Even the waiters ignore him. Like Stevie Smith’s poem, this is such a simple poem, but real meaning lurks beneath the surface.

Additional Resources:

If you are teaching or studying Not Waving But Drowning at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It’s only £2 and includes:

- 4 pages of activities that can be printed and folded into a booklet for use in class, at home, for self-study or revision.

- Study Questions with guidance for how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample Point, Evidence, Explanation paragraph for essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining Speaker and Voice.

- A fun crossword-quiz, perfect for a recap lesson or for revision.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Stevie Smith’s poem? How do you respond to the criticism of bystanders in the poem? What do you think makes this poem so effective? Why not share your thoughts, add an idea, or ask a question in the comment section below. And, for daily nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, don’t forget to find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

I love your commentaries in general. I tell my students your discussions are significantly worth reading with incredible insights and creatively engaged responses. I do, however, quibble with your discussions of assonance. You seem to assume that repeated use of the same vowel letter produces assonance. However, I feel pretty certain that assonance is the repetition of the same vowel sound. In the case of this poem, your claim of assonance in the line ‘Oh, no no no it was too cold’ is mostly right, except that you include the word ‘too’ in your identification. This word has a different vowel sound from ‘oh’, ‘no’ and ‘cold’. I have seen you discuss assonance in similarly (erroneous?) ways in your analysis of other poems. Perhaps my understanding of assonance is limited but I think I am right in thinking it is the repetition of a vowel sound rather than a vowel. Regardless, thank you for you wonderful commentaries on poetry! Very helpful and provocative, indeed.

Hi Paul,

Thank you for your comment. You’re right about assonance. Like alliteration, it’s in the sound, not the letter. In the line quoted, ‘Oh no no no it was too cold,’ there are two O sounds: the ’round’ O sound ‘oh no no no… cold’ and the long OO sound (‘too’). I’ve edited the blog so that it reads ‘assonant sounds’ rather than ‘assonance’, a phrase which can encompass the combination of both sounds.

Thanks for the good spot; i’m glad you and your students enjoy the blog and find it useful.

First, thank you for such a wonderful analysis, it really helps for my Literature assignments. In my interpretation of the poem, I describe the use of the personal pronoun ‘I’ as the dead man’s voice or his regretful ghost commenting after his death. Is this a fair assumption or is it more accurate to say that

it is his death itself that is speaking and the loss of life has something to say on the man’s behalf.

Hi BP,

Thank you for your comment. I like your first idea very much, that the ‘I’ is the ‘dead man’s voice or his regretful ghost’ come back to speak to us after his death. As for your second idea, that Death itself is speaking, I’m not so sure. I think there are enough different voices in this poem already (the narrator, the dead man, and the bystanders) without adding the voice of death into the mix.