Charles Tennyson Turner finds himself unexpectedly moved by a tiny tragedy.

“Turner’s recurrent subject is small creatures, small persons, small objects, dinky things…”

Valentine Cunningham, biographer of Charles Turner

This might seem like a bit of a random question, but when was the last time you killed a fly? If you can even remember such a trivial moment, how did you feel afterwards? I’d hazard a guess that, if you should tread on an ant or squash an insect, you’ll probably shrug and get on with our day. Well, when Charles Tennyson Turner accidentally crushed a fly in a book, not only did he pause to wonder about the fly’s life, but he put everything else aside and set to work composing a poem about its unfortunate death. And not just any poem – a sonnet, of all things! Normally reserved for elevated topics such as love, Turner puts this most elegant of poetic forms to work eulogising the fly’s demise. While the poem is certainly light-hearted, and even darkly comic in some parts, it also has a serious point to make. Turner plays upon universal fears of dying unexpectedly, and laments that, when it’s time to depart this mortal coil, we might not leave anything as worthy as a fly’s detached wings behind:

Some hand, that never meant to do thee hurt, Has crushed thee here between these pages pent; But thou has left thine own fair monument, Thy wings gleam out and tell me what thou wert: Oh! that the memories, that survive us here, Were half as lovely as these wings of thine. Pure relics of a blameless life, that shine Now thou art gone: Our doom is ever near: The peril is beside us day by day; The book will close upon us, it may be, Just as we lift ourselves to soar away Upon the summer airs. But, unlike thee, The closing book may stop our vital breath, Yet leave no lustre on our page of death.

I love the faux-innocent expression of the opening to this poem: Some hand… has crushed thee here, as if the speaker stumbled across the book and found the fly already squashed inside. I’ve got no proof, but I’m convinced it was our dear speaker himself who killed the fly – how else is he supposed to know that the hand was never meant to do thee harm unless it was his own? With a cheeky wink, the poem describes the fly as blameless and therefore implies that the speaker is, perhaps, not. His instinctive attempt to deflect blame for the fly’s death onto another hand, rather than owning up to the deed himself, makes me wonder if he is really as guileless and honest as he sounds throughout. Cleverly, this humorous opening foreshadows the comparison of human and insect lives that will come later. The ability to lie, cheat, and dissemble is particular to humans – you won’t catch a fly pretending someone else is making that annoying buzzing sound.

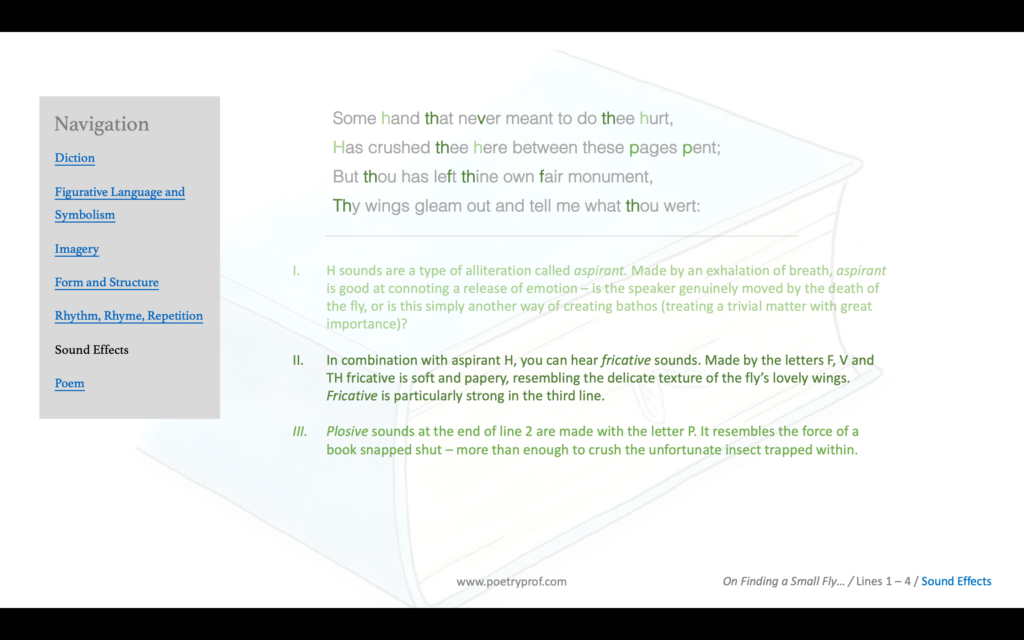

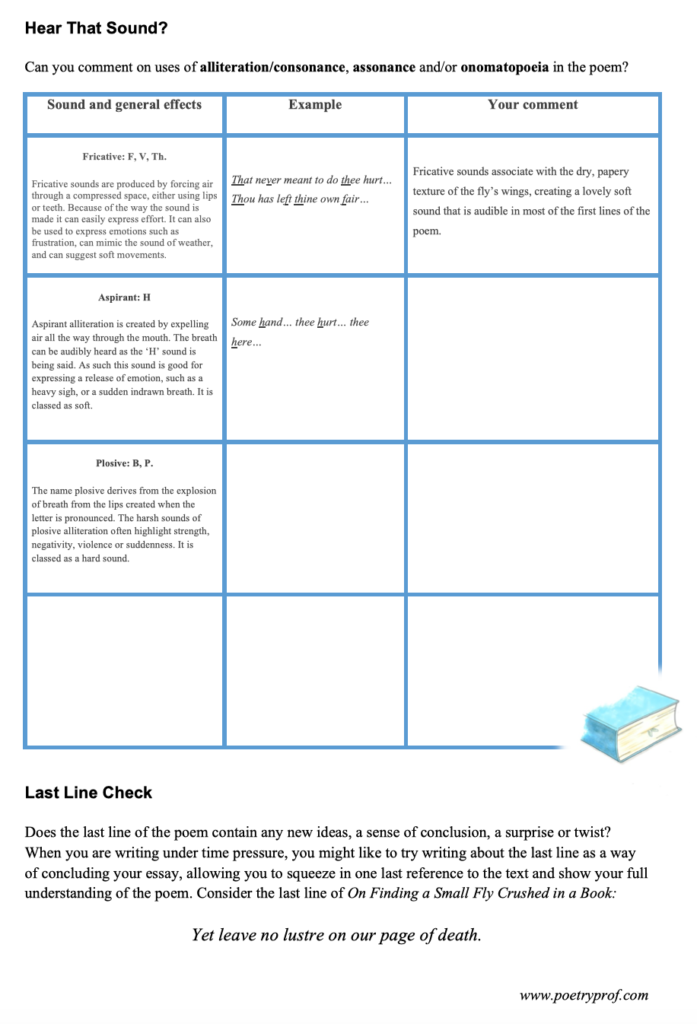

It takes a while for the comparisons between human and fly to coalesce. First of all, the speaker waxes lyrical over the fly’s wings; while its body has been crushed the wings are luckily left undamaged, protruding from between the pages and still lovely. When describing these wings, Turner uses diction to do with ‘light,’ such as gleam, shine, and lustre (meaning a gentle sheen or glow, like that given off by polished metal) to create an image of shimmering, translucent beauty. While a fly is hardly one of God’s most beautiful creations, if the poem achieves anything, it’s to remind us of the miracle of even the humblest of nature’s denizens. We are encouraged to take a fresh perspective on the fly by seeing the papery wings up close, delicately veined in green and gold, thin as silk but capable of incredible manoeuvrability while in flight. The visual imagery is unexpectedly beautiful, as if the wings are those of an angel rather than a common household fly. The sounds of the opening lines are equally delicate: fricatives (made with the letters F, V and TH) combined with aspirant (using the letter H) summon to mind the soft, papery texture of the lovely wings in words such as: survive, hand, harm, has, here, half, left, fair, life, that, thee, these, thou, and thine. A particularly startling moment occurs at the end of line 2 when Turner instead employs hard plosive alliteration (pages pent) to evoke the snap of the closing book. The contrast between hard and soft sounds is sudden and jarring, creating a momentary ‘thud’ which ends the life of the poor fly.

The unexpectedly beautiful imagery describing the wings is compounded using a method called apostrophe – but not the kind of apostrophe that you would have learned about in all those boring grammar classes. In poetry, apostrophe is a method by which something or someone is directly addressed by whoever’s speaking. One of the most famous examples of apostrophe in all poetry is John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, in which he speaks directly to an urn he once saw in a museum, calling it ‘a ‘mysterious priest’, an ‘unravished bride’ and ‘foster-child of silence’ (Keats was fond of renaming things in his poems). In the case of the fly’s wings, Turner renames them relics, a metaphor with strong religious connotations. Although the word can be used in a general sense to mean something of important historical significance, its literal meaning is actually ‘the remains of a holy person’ – that’s right, the word relics points to the bones and body parts of deceased saints! Additionally, the fly is described as both pure and blameless, strongly implying it was a ‘saintly’ creature in life. Throw in all that light imagery, and it’s as if the fly shines with an angelic aura. In another example of apostrophe/metaphor Turner addresses the wings as a fair monument. The word monument is grandiose; you might hear it in the context of a grand construction like the pyramids of Egypt, monuments to the greatness of the Pharoahs, or Victorians interring wealthy ancestors inside grand crypts. A monument is normally built for posterity as an act of remembrance, so you can connect the word monument with the word memories in the fifth line.

With all this elevated diction, it’s easy to think that Turner is getting a bit overwrought by the death of a single fly. But he hasn’t lost his mind – he’s purposefully employing a type of satire called bathos in which seemingly trivial happenings are treated with undue importance. As we follow the direction of Turner’s thoughts, it’s clear that the death of the fly is significant not because of what it means for the fly, but because of what it means for people: the fly’s sudden and unexpected end reminds Turner that death waits for all living things, flies and people too. This realisation comes at the halfway point of the sonnet, a moment called turn or volta, which changes the direction of the idea, shifts the poem in tone, or develops a new angle of approach. Where precisely the turn is located depends on the type of sonnet. Broadly speaking, two types were ‘trending’ during Turner’s life: the Petrarchan sonnet and the Shakespearean sonnet. Named after famous writers, one Italian, one English, both have fourteen lines structured in a particular way: an opening section of eight lines (called the octave) followed by six lines called the sestet which, in a Shakespearean sonnet, normally finishes in a rhyming couplet. Shakespeare was fond of ‘turning’ in the final couplet, which might provide an ironic, humorous or moving ‘twist’ on the poem he’d just written. Petrarch was more inclined to turn between the octave and the sestet. You can see that Turner follows Petrach with regard to his turn: halfway through the eighth line (the closing line of the octave) he uses two colons to bracket the phrase our doom is ever near. With the word our, he reveals that he’s no longer thinking about the fly, but about people in general, realising that we are just as exposed to happenstance, accident and mishap as any living creature. This assertion hits with the force of epiphany and paves the way for the second part of his sonnet.

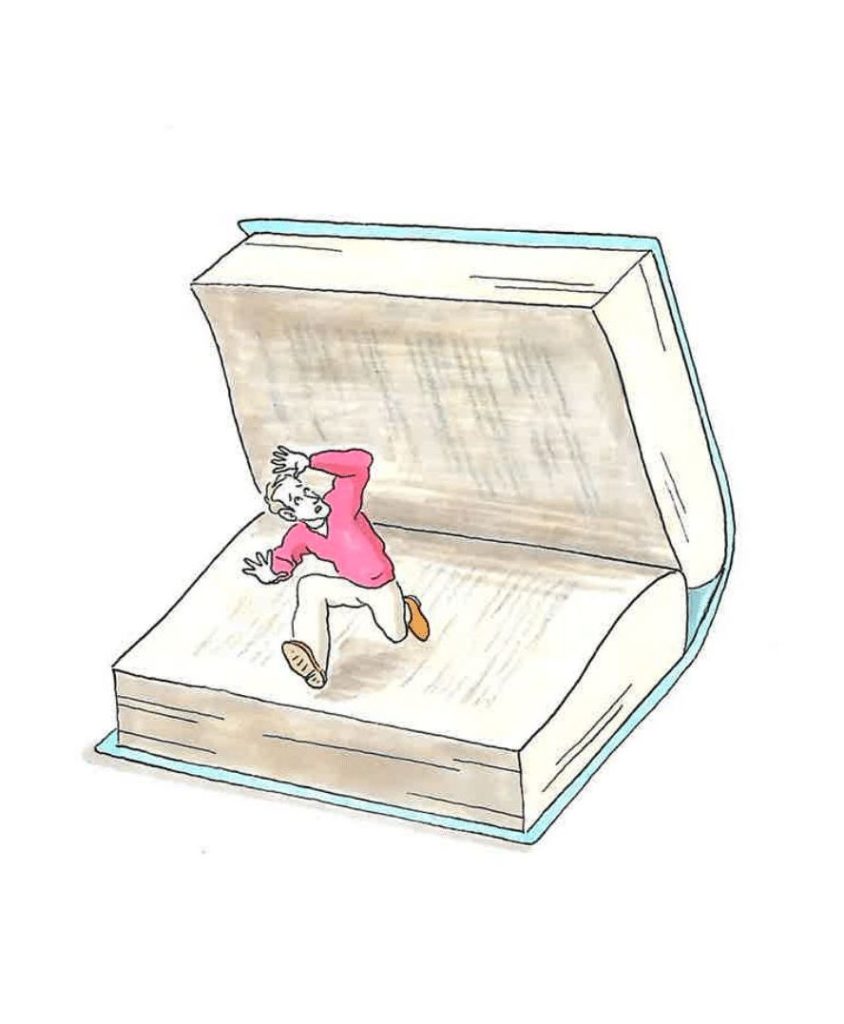

From here on, the poem becomes darker and more pensive. The speaker’s tone of voice changes completely as he abandons his ‘light’ words and starts to use ominous-sounding words such as doom, peril and death. Turner imagines death stalking us like a hunter, ever near and right beside us, even using repetition (day by day) to create the impression that it’s coming closer every moment. This ‘stalking’ feel is strengthened by the regular rhythm of the poem, a steady ‘de-dum, de-dum, de-dum…’ of iambic pentameter, like the music from Jaws that plays every time the shark is about to strike from the depths. His imaginative thoughts of dying culminate in an incredible moment of dark humour when Turner imagines a giant book closing, not upon a fly, but on people who try vainly to escape (just as we lift ourselves to soar away) – yet are crushed to death out of nowhere, a moment reminding me of all those childhood cartoons when a piano, rock, or heavy weight might fall out of a clear sky and flatten the hapless hero into the ground! But behind the black comedy is a serious and universal fear: any of us at any time might be caught in an unexpected accident which takes our life away before we’ve had time to put our affairs in order. There’s an unbearable tension in the imagery of escape that Turner draws for us; we seem poised to take flight and soar into the summer airs. He uses enjambment to run one line into the other, and suddenly gives us several long vowel sounds (ourselves, soar, away, airs) drawing out this hopeful moment – but flight is impossible for humans, and the book snaps shut, squashing us inside. This metaphor for dying is both hilarious and horrific, suggesting that there is no hope of escaping death when it’s our time to go.

It is this last point which makes Turner’s poem more than just another ‘fear of death’ poem. It’s not only that he’s afraid to die; he’s afraid to die before he’s had a chance to cement his legacy, build that fair monument by which people will remember him after he’s gone. I think this must have been a very real issue for Turner. Devoting his mind and time to creative work – what if nobody reads your poems and you are unsuccessful up until the day you die? Notwithstanding the fact that Turner was the brother of a famous and most successful writer of his era, perhaps this was playing on his mind as he put his own pen to paper? Of course, the desire to leave a legacy isn’t just the provenance of writers. Wanting people to remember you, being reassured that you are important to the people around you, is a universal concern that you should be able to understand, even if you don’t share it yourself.

Overall, the poem explores the idea of ‘what we leave behind us’ in a semi-humorous way. It’s not a terribly tragic poem, but there’s certainly a darkness to it, particularly in the idea that death is just around the corner, and we won’t necessarily see it coming or have our affairs in order when it strikes. The worry that we may abruptly vanish without a trace is quite existential. We all like to think that we’ll leave our lustre (make a mark) on the world, that people will have something to say about us after we’re gone. But here – no, people just vanish as if they never existed, unable to smear the page of death with even as much as a blot of ink. At the very end, Turner deploys sound brilliantly to create a feeling of finality: hard consonants pepper the final two lines (closing, book, stop, breath, page, death) and the effect of the closing couplet (‘breath/death’) is also jarringly abrupt.

The end of the poem leaves us in no doubt: unless you happen to be a fly, once you’re gone, you’re gone.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- The Flea by John Dunne

Proving that no subject is too humble for poetry, this coarse and wickedly funny poem imagines a flea biting both a man and a woman – and using that as an excuse as to why she should give up her ‘maidenhead’ (virginity) to the poem’s speaker.

- Silkworms and Spiders by Charles Tennyson Turner

It’s not like every sonnet Turner wrote was dedicated to insects, but here’s another one about two more tiny creatures.

- Flies by Alice Oswald

Dead flies on a windowsill are a common enough sight – but Alice Oswald uses this as the starting point for an imaginative journey, wondering where in the world these flies may have been. A brilliant, thought-provoking poem.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs.

- A sample ‘Point-Evidence-Explanation-Analysis’ paragraph to model essay writing.

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem.

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on explaining the sonnet form so you can recognise this common type of poem in the future.

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap – now with answers provided separately.

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision.

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete Model Essay for you to use as a style guide.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this breakdown of Charles Turner’s poem? Can you think of other poems that treat a trivial event with such importance? Do you agree that the poem is both funny and serious? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.